Thyroid Hormones T3 and T4 as Central Regulators of Basal Metabolic Rate: Molecular Mechanisms, Metabolic Integration, and Therapeutic Potential

Thyroid hormones (THs), thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), are primary determinants of mammalian basal metabolic rate (BMR), regulating energy expenditure, thermogenesis, and the metabolism of carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins across...

Thyroid Hormones T3 and T4 as Central Regulators of Basal Metabolic Rate: Molecular Mechanisms, Metabolic Integration, and Therapeutic Potential

Abstract

Thyroid hormones (THs), thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), are primary determinants of mammalian basal metabolic rate (BMR), regulating energy expenditure, thermogenesis, and the metabolism of carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins across multiple tissues. This article synthesizes foundational and contemporary research on the genomic and non-genomic mechanisms of TH action, exploring their cell-autonomous regulation via deiodinases and transporters. It further examines the pathological metabolic consequences of thyroid dysfunction in obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome, and critically evaluates emerging therapeutic strategies, including TH receptor-beta selective agonists and the metabolite 3,5-T2, which aim to harness THs' metabolic benefits while mitigating cardiovascular risks. The content is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, providing a comprehensive framework for understanding THs' role in metabolic physiology and their potential as therapeutic targets.

The Fundamental Mechanisms: How Thyroid Hormones Govern Cellular Metabolism

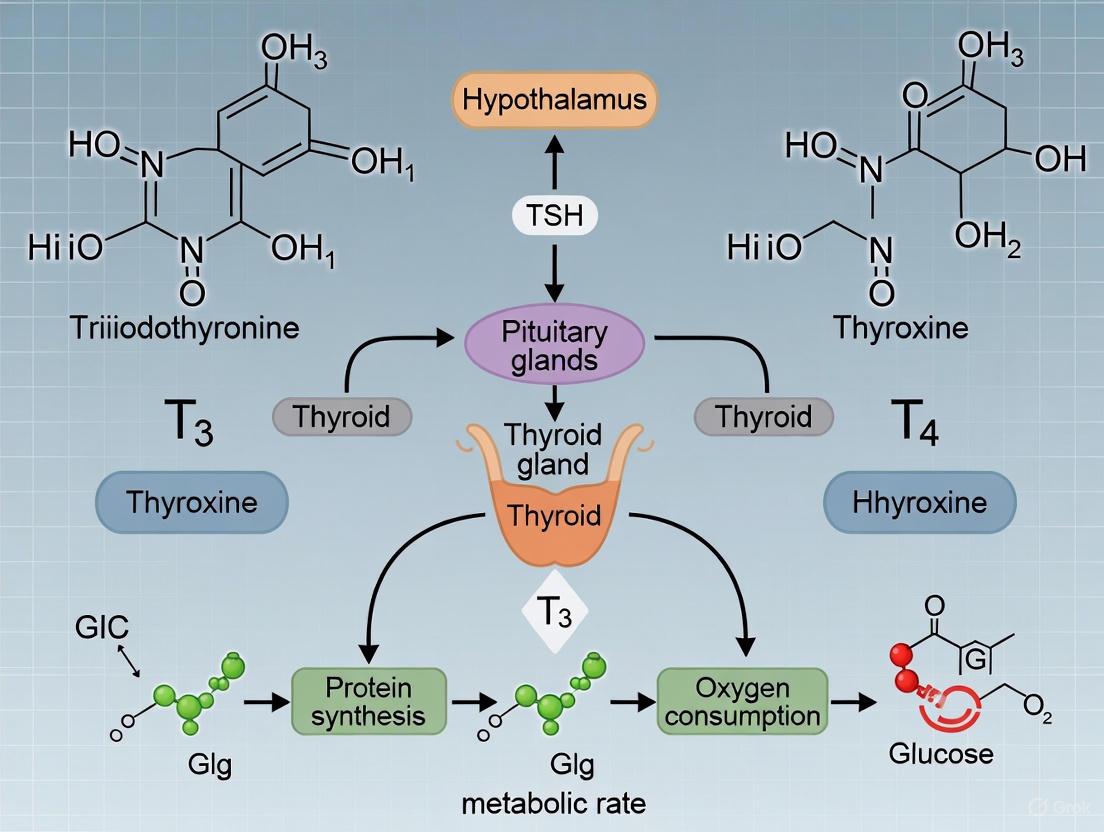

The hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis represents a critical neuroendocrine system responsible for the precise regulation of thyroid hormone (TH) synthesis, secretion, and systemic homeostasis. This sophisticated regulatory circuit integrates central neural signals with peripheral endocrine feedback to maintain metabolic stability across virtually all organ systems. Within the context of basal metabolic rate (BMR) research, the HPT axis serves as the principal determinant of metabolic set-point, with the active thyroid hormone triiodothyronine (T3) functioning as the primary effector molecule. This technical review comprehensively examines HPT axis physiology, TH signaling mechanisms, experimental methodologies for investigating thyroid function, and the intricate relationship between thyroid homeostasis and energy expenditure. Understanding these complex regulatory pathways provides fundamental insights for developing targeted therapeutic interventions for metabolic disorders.

Core Physiology of the HPT Axis

The hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis operates as a classic neuroendocrine feedback system that maintains thyroid hormone concentrations within a narrow physiological range, thereby ensuring appropriate metabolic function throughout the body [1].

Hierarchical Hormonal Regulation

The HPT axis functions through a sequential hormonal cascade that originates in the central nervous system and culminates in thyroid hormone release from the peripheral thyroid gland:

- Hypothalamic Release: The neuroendocrine cascade initiates with hypothalamic secretion of thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) from the paraventricular nucleus (PVN). TRH is synthesized as a preprohormone in the neuronal cell bodies of the PVN and transported to the median eminence, where it is released into the hypothalamic-hypophyseal portal system [2] [3].

- Pituitary Stimulation: Upon reaching the anterior pituitary gland, TRH binds to G-protein coupled receptors on thyrotropes, activating the phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C (PLC) signal transduction pathway. This intracellular signaling cascade culminates in the synthesis and secretion of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) [2].

- Thyroid Activation: TSH binds to TSH receptors (TSH-R) on the basolateral membrane of thyroid follicular cells, activating adenylyl cyclase and increasing intracellular cAMP levels via Gs-protein coupling. This stimulation triggers the five essential steps of thyroid hormonogenesis: thyroglobulin synthesis, iodide uptake, iodination of thyroglobulin, storage of iodinated thyroglobulin in follicular colloid, and proteolytic release of finished thyroid hormones [2].

Table 1: Key Hormones of the HPT Axis and Their Primary Functions

| Hormone | Origin | Primary Function | Regulatory Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone (TRH) | Hypothalamus | Stimulates TSH synthesis and release from anterior pituitary | Initiates HPT axis activation; regulated by negative feedback from TH |

| Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH) | Anterior Pituitary | Stimulates thyroid follicular cells to produce and release T4 and T3 | Primary regulator of thyroid gland function; sensitive to negative feedback |

| Thyroxine (T4) | Thyroid Gland | Prohormone; primary secretory product of thyroid | Circulating reservoir for active T3; provides negative feedback |

| Triiodothyronine (T3) | Thyroid Gland & Peripheral Tissues | Active hormone; binds to nuclear receptors | Primary mediator of TH effects on metabolism; potent negative feedback |

Feedback Control Mechanisms

The HPT axis maintains thyroid homeostasis through sophisticated negative feedback loops that precisely regulate hormone production:

- Long-Loop Feedback: Circulating T3 and T4 exert negative feedback inhibition at both pituitary and hypothalamic levels. The pituitary thyrotropes are particularly sensitive to free TH concentrations, with elevated levels suppressing TSH synthesis and secretion [1] [4].

- Short-Loop Feedback: TSH exerts feedback inhibition on hypothalamic TRH release, although this mechanism is less dominant than TH-mediated feedback [1].

- Ultra-Short Feedback: TRH can autoregulate its own secretion through local feedback mechanisms within the hypothalamus [1].

The feedback control system demonstrates hierarchical sensitivity, with the pituitary gland exhibiting greatest responsiveness to circulating TH levels, followed by hypothalamic centers. This tiered sensitivity allows for precise set-point regulation of thyroid function despite fluctuating metabolic demands [5] [1].

Diagram 1: Core HPT Axis Feedback Loop. This schematic illustrates the hierarchical structure and negative feedback regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis.

Thyroid Hormone Synthesis and Signaling Mechanisms

Biochemical Synthesis of Thyroid Hormones

The thyroid gland employs a unique biochemical pathway for hormone synthesis that requires specialized cellular machinery and the essential trace element iodine [2]:

- Thyroglobulin Production: Thyroid follicular cells (thyrocytes) synthesize thyroglobulin (Tg), a large glycoprotein precursor that serves as the scaffold for thyroid hormone synthesis. Tg is produced in the rough endoplasmic reticulum, processed through the Golgi apparatus, and packaged into vesicles for exocytosis into the follicular lumen [2].

- Iodide Transport and Oxidation: The Na+/I- symporter (NIS) actively transports iodide from the circulation into thyrocytes against a concentration gradient. Iodide then diffuses to the apical membrane and is transported into the colloid by pendrin transporters. At the colloid-thyrocyte interface, thyroid peroxidase (TPO) oxidizes iodide (I-) to iodine (I2) using hydrogen peroxide generated by NADPH oxidase [2].

- Organification and Coupling: TPO catalyzes the incorporation of oxidized iodine onto tyrosine residues within thyroglobulin, forming monoiodotyrosine (MIT) and diiodotyrosine (DIT). Subsequently, TPO mediates the coupling of iodinated tyrosine residues: MIT + DIT forms triiodothyronine (T3), while two DIT molecules form thyroxine (T4) [2].

- Storage and Release: The iodinated and coupled thyroglobulin is stored extracellularly in the follicular colloid until stimulated by TSH. Upon TSH stimulation, thyrocytes endocytose colloid, lysosomal enzymes proteolyze thyroglobulin, and free T4 (80%) and T3 (20%) are released into circulation via MCT8 transporters [2].

Table 2: Key Components of Thyroid Hormone Synthesis and Their Functions

| Component | Location | Function | Clinical/Research Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium-Iodide Symporter (NIS) | Basolateral membrane of thyrocytes | Active transport of iodide into thyroid cells | Target for radioiodine imaging and therapy |

| Thyroid Peroxidase (TPO) | Apical membrane of thyrocytes | Oxidation, organification, and coupling reactions | Major autoantigen in autoimmune thyroid disease |

| Thyroglobulin (Tg) | Follicular colloid | Scaffold protein for thyroid hormone synthesis | Tumor marker for thyroid cancer recurrence |

| Monocarboxylate Transporter 8 (MCT8) | Basolateral membrane of thyrocytes | Cellular efflux of thyroid hormones | Mutations cause Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome |

Multimodal Signaling Pathways

Thyroid hormones exert their effects through multiple distinct signaling mechanisms that can be classified into four primary types based on receptor involvement and subcellular localization [6]:

- Type 1 Signaling (Canonical Genomic): This classical pathway involves binding of T3 to nuclear thyroid hormone receptors (TRs) that dimerize with retinoid X receptors (RXRs) and bind to thyroid response elements (TREs) in target gene promoters. The consensus TRE sequence is typically a direct repeat with a 4-nucleotide spacer (DR4): 5'(A/G)GG(A/T)CANNNN(A/G)GG(A/T)CA3' [6] [7]. Ligand binding induces conformational changes in TRs that facilitate coactivator recruitment (e.g., NCoA, SRC/p160 family) and displacement of corepressors (e.g., NCoR, SMRT), thereby modulating transcriptional activity [6].

- Type 2 Signaling (Noncanonical Genomic): In this variant genomic pathway, TRs indirectly associate with DNA through protein-protein interactions with other transcription factors (e.g., AP-1 complexes) without direct DNA binding. This tethering mechanism allows thyroid hormones to modulate gene expression at genomic sites lacking canonical TREs [6].

- Type 3 Signaling (Cytoplasmic TR-Mediated): Cytoplasmic TRs can participate in nongenomic signaling by interacting with kinase cascades, including the PI3K and MAPK pathways. The p30 protein, a truncated TRα1 translation product lacking the DNA-binding domain, has been implicated in these rapid membrane-initiated actions [6].

- Type 4 Signaling (TR-Independent): Some rapid thyroid hormone effects occur independently of classical TRs, potentially mediated by integrin αVβ3 membrane receptors or direct allosteric modulation of enzymatic activity (e.g., μ-crystallin) [6].

Diagram 2: Thyroid Hormone Signaling Pathways. This schematic classifies the four distinct mechanisms through which thyroid hormones mediate cellular effects.

Intracellular Activation and Metabolism

The biological activity of thyroid hormones is critically dependent on intracellular activation and metabolism that occurs primarily in peripheral tissues:

- Cellular Uptake: Thyroid hormones enter cells via specific transporter proteins, including monocarboxylate transporters (MCT8, MCT10) and organic anion transporting polypeptides (OATPs). MCT8 demonstrates particularly high affinity for T3 and shows tissue-specific expression patterns [3].

- Deiodination Pathways: The activation of thyroxine (T4) to the biologically active triiodothyronine (T3) is catalyzed by selenoenzyme deiodinases. Type 1 deiodinase (DIO1) in liver and kidney and type 2 deiodinase (DIO2) in brain, pituitary, brown adipose tissue, and skeletal muscle convert T4 to T3 [2] [3]. Type 3 deiodinase (DIO3) inactivates both T4 and T3 to reverse T3 (rT3) and T2, respectively, serving as a critical regulatory brake on thyroid hormone action [3].

- Receptor Binding and Isoform Specificity: Intracellular T3 binds with high affinity to nuclear thyroid hormone receptors (TRα1, TRβ1, TRβ2) which function as ligand-regulated transcription factors. TR isoforms display distinct tissue distributions: TRα1 predominates in skeletal muscle, heart, and brown adipose tissue, while TRβ1 is abundant in liver and kidney, and TRβ2 is primarily expressed in anterior pituitary and hypothalamus [7]. This isoform specificity enables tissue-selective responses to thyroid hormone.

Methodologies for Investigating HPT Axis Function

Standard Hormonal Assessments

Comprehensive evaluation of HPT axis function requires a multifaceted testing approach that interrogates different levels of the regulatory hierarchy:

- TSH Measurement: Serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) represents the most sensitive and specific marker of primary thyroid dysfunction. The log-linear relationship between TSH and free T4 allows detection of subtle perturbations in thyroid homeostasis [2] [1]. Current third-generation immunometric assays achieve functional sensitivities of approximately 0.01-0.02 mIU/L, enabling discrimination of thyrotoxic states [1].

- Thyroid Hormone Quantification: Free thyroxine (FT4) and free triiodothyronine (FT3) measurements provide assessment of biologically active hormone fractions, unaffected by variations in binding proteins. Equilibrium dialysis represents the gold standard methodology, though most clinical laboratories employ automated immunoassays with varying methodological limitations [2] [4].

- Dynamic Testing: TRH stimulation testing involves intravenous administration of synthetic TRH (200-500 μg) with serial TSH measurements at 0, 30, and 60 minutes. This protocol distinguishes pituitary (blunted response) from hypothalamic (delayed and prolonged response) causes of central hypothyroidism [5] [1].

Table 3: Standard Biochemical Assessment of Thyroid Function

| Parameter | Biological Significance | Reference Intervals | Interpretation Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| TSH | Primary marker of HPT axis set-point | 0.4-4.0 mIU/L (adult) | Elevated in primary hypothyroidism; suppressed in hyperthyroidism |

| Free T4 | Bioactive thyroxine fraction | 0.8-2.0 ng/dL | Direct measure of thyroid secretory capacity |

| Free T3 | Bioactive triiodothyronine | 2.0-4.5 pg/mL | More sensitive marker of thyrotoxicosis |

| Reverse T3 | Metabolic inactivation product | 10-24 ng/dL | Elevated in nonthyroidal illness syndrome |

| Thyroglobulin | Thyroid tissue marker | 1.5-30 ng/mL | Monitoring for thyroid cancer recurrence |

| Thyroid Antibodies | Autoimmune activity | TPOAb <35 IU/mL; TgAb <20 IU/mL | Diagnostic for autoimmune thyroid disease |

Experimental Protocols for BMR Research

Investigation of thyroid hormone effects on basal metabolic rate requires carefully controlled experimental conditions and precise measurement methodologies:

- Indirect Calorimetry Protocol: The gold standard for assessing energy expenditure involves measurement of oxygen consumption (VO2) and carbon dioxide production (VCO2) using closed-circuit respirometry systems. The experimental workflow includes:

- Acclimation Period: Animals or human subjects acclimatize to metabolic chambers for 2-4 hours prior to data collection to minimize stress artifacts.

- Environmental Control: Maintain thermoneutral temperature (28-30°C for mice; 22-24°C for humans) to eliminate thermoregulatory energy expenditure.

- Fasting State: Conduct measurements after 4-6 hour fast to eliminate diet-induced thermogenesis.

- Data Collection: Record VO2 and VCO2 at 1-minute intervals for 2-4 hours during inactive circadian phase.

- Calculation: Compute BMR using Weir equation: BMR (kcal/day) = [3.9(VO2) + 1.1(VCO2)] × 1.44 [3].

- Tissue-Specific Metabolic Assessment: For investigation of organ-level contributions to energy expenditure:

- Tissue Explants: Isolate fresh tissues (liver, skeletal muscle, brown adipose tissue) and maintain in oxygenated Krebs-Ringer buffer.

- Ex Vivo Respiration: Measure oxygen consumption using Clark-type oxygen electrodes or Seahorse extracellular flux analyzers.

- Substrate Utilization: Assess fuel preference by modifying substrate availability (glucose, fatty acids, pyruvate) in assay media.

- Mitochondrial Isolation: Fractionate mitochondrial fractions by differential centrifugation for direct assessment of mitochondrial function [3].

- Molecular Analysis of Thermogenic Pathways:

- RNA Isolation and qPCR: Extract total RNA from target tissues using guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Perform quantitative PCR for UCP1, DIO2, PGC-1α, and other thermogenic markers.

- Western Blot Analysis: Resolve tissue lysates by SDS-PAGE, transfer to membranes, and probe with specific antibodies against thyroid hormone receptors, deiodinases, and mitochondrial proteins.

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation: Crosslink proteins to DNA with formaldehyde, immunoprecipitate TR-bound chromatin fragments, and quantify enrichment at target gene promoters [3] [6].

Diagram 3: Experimental Workflow for BMR Assessment. This flowchart outlines the sequential steps for precise measurement of basal metabolic rate in thyroid research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Thyroid Hormone Action

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thyroid Hormone Receptor Agonists/Antagonists | GC-1 (TRβ-selective), KB-141 (TRβ-selective), DITPA (cardiac-selective) | Isoform-specific functional studies | Selectivity profiles must be verified in specific experimental systems |

| Deiodinase Inhibitors | Iopanoic acid (nonselective), Gold thioglucose (DIO1 inhibitor) | Modulation of local T3 availability | Vary in specificity and potency across deiodinase isoforms |

| Transport Inhibitors | Silychristin (MCT8 inhibitor), BSP (OATP inhibitor) | Study of cellular TH uptake | Limited isoform specificity for many available compounds |

| Antibodies for Protein Detection | Anti-TRα, Anti-TRβ, Anti-DIO2, Anti-UCP1 | Western blot, immunohistochemistry, ChIP | Validation in knockout models essential for specificity confirmation |

| ELISA/Kits | TSH ELISA, Total T4/T3 ELISA, Free T4/T3 ELISA, rT3 ELISA | Hormone quantification | Method-dependent variations in accuracy, particularly for free hormone assays |

| Molecular Biology Tools | TRE reporter constructs, TR expression plasmids, siRNA/shRNA libraries | Gene regulation studies | Careful titration required to avoid overexpression artifacts |

| Animal Models | TRα/- and TRβ-/- mice, MCT8-deficient mice, DIO2-/- mice | In vivo functional studies | Compensation during development may complicate interpretation |

Thyroid Hormone Regulation of Basal Metabolic Rate

Central Regulation of Energy Homeostasis

The hypothalamus serves as the primary integration center for metabolic signals that modulate HPT axis function and thereby influence systemic energy expenditure:

- Tanycyte-Mediated Regulation: Specialized ependymal cells (tanycytes) lining the third ventricle express high levels of DIO2, converting T4 to active T3 for paracrine signaling to TRH neurons in the paraventricular nucleus. This local T3 production establishes a critical interface between circulating thyroid hormones and central regulation of metabolism [3].

- Nutrient-Sensing Pathways: Hypothalamic nutrient sensing integrates signals from circulating hormones (leptin, ghrelin, insulin) and nutrients to modulate HPT axis activity. During fasting, reduced leptin signaling and elevated AgRP/NPY activity suppress TRH expression, consequently decreasing HPT axis activity and reducing energy expenditure as an adaptive response to negative energy balance [3].

- Autonomic Nervous System Integration: Thyroid hormones modulate sympathetic outflow to peripheral metabolic tissues, particularly brown adipose tissue. T3 acts in the ventromedial hypothalamus to increase BAT sympathetic nerve activity, thereby stimulating thermogenesis through β-adrenergic receptor activation and UCP1-mediated uncoupling of mitochondrial respiration [3].

Peripheral Mechanisms of Metabolic Regulation

Thyroid hormones exert direct effects on multiple peripheral tissues to coordinate systemic energy expenditure:

- Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Function: T3 stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis through upregulation of PGC-1α and nuclear respiratory factors (NRF-1, NRF-2). Additionally, T3 regulates mitochondrial oxidative capacity by inducing nuclear-encoded mitochondrial enzyme genes, including components of the electron transport chain and fatty acid β-oxidation pathway [2] [3].

- Substrate Cycling: Thyroid hormones coordinate substrate utilization through tissue-specific mechanisms:

- Hepatic Metabolism: T3 increases hepatic glucose production through induction of gluconeogenic enzymes (glucose-6-phosphatase, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase) and enhances fatty acid oxidation while simultaneously promoting de novo lipogenesis [3] [7].

- Skeletal Muscle: T3 shifts muscle fiber composition toward faster contractile properties, increases glucose uptake through GLUT4 translocation, and enhances fatty acid oxidation capacity [2].

- Adipose Tissue: In white adipose tissue, T3 promotes lipolysis and reduces lipid storage capacity. In brown adipose tissue, T3 synergizes with sympathetic signaling to induce UCP1 expression and thermogenic capacity [3].

- Cardiac Output Modulation: Thyroid hormones increase cardiac contractility, heart rate, and stroke volume through combined effects on ion channel expression (SERCA, Na+/K+ ATPase), β-adrenergic receptor density, and myocardial energy metabolism, thereby enhancing circulatory support for increased metabolic demand [2].

Pathophysiological Considerations in Metabolic Regulation

Alterations in HPT axis function produce characteristic metabolic phenotypes that illustrate the critical role of thyroid hormones in energy homeostasis:

- Hypothyroidism: The metabolic hallmarks of thyroid hormone deficiency include reduced basal metabolic rate (decreased by up to 50% in severe cases), decreased thermogenesis, weight gain despite reduced appetite, hyperlipidemia, and insulin resistance in muscle and adipose tissue [2] [4].

- Hyperthyroidism: Thyroid hormone excess produces a hypermetabolic state characterized by increased BMR (elevated by 30-100%), enhanced thermogenesis, weight loss despite increased appetite, insulin resistance with increased hepatic glucose production, and increased lipid mobilization [2] [7].

- Non-Thyroidal Illness Syndrome: During systemic illness, proinflammatory cytokines suppress HPT axis function through reduced TRH secretion, altered deiodinase activity (decreased DIO1, increased DIO3), and reduced thyroid hormone binding proteins, resulting in a low T3 state that may represent an adaptive energy conservation mechanism [5] [1].

Emerging Research Directions and Therapeutic Implications

Novel Regulatory Mechanisms

Recent research has revealed previously unappreciated dimensions of thyroid homeostasis that expand our understanding of HPT axis regulation:

- Microbiota-Thyroid Axis: The gut microbiota composition influences thyroid hormone homeostasis through several mechanisms, including modification of enterohepatic cycling of thyroid hormones, conversion of iodide to iodine, generation of short-chain fatty acids that modulate deiodinase activity, and regulation of systemic inflammation that impacts HPT axis function [8].

- Immune System Interactions: Pattern recognition receptors (e.g., NOD1) respond to microbial components and influence thyroid hormone function through immune system activation. NOD1-dependent signaling pathways have been demonstrated to alter thyroid hormone metabolism and contribute to obesity phenotypes in experimental models [8].

- Allostatic Regulation: The HPT axis demonstrates adaptive plasticity in its set-point regulation under conditions of chronic stress, circadian disruption, and metabolic challenge. This allostatic regulation involves complex integration of signals from other neuroendocrine systems, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and reproductive axis [1].

Therapeutic Applications and Drug Development

Understanding the molecular mechanisms of thyroid hormone action provides opportunities for targeted therapeutic interventions:

- TRβ-Selective Agonists: Compounds with selective affinity for TRβ receptors (e.g., eprotirome, resmetirom) demonstrate beneficial metabolic effects on lipid metabolism and body weight with reduced cardiac and bone side effects, representing promising approaches for treating dyslipidemia and NASH [7].

- Central Thyroid Hormone Modulation: Strategies targeting hypothalamic deiodinase activity or TRH expression may permit fine-tuning of metabolic rate without producing peripheral thyrotoxicosis, potentially offering novel approaches for obesity management [3].

- Mitochondrial-Targeted Approaches: Compounds that recapitulate the mitochondrial effects of thyroid hormones without genomic actions could enhance oxidative metabolism while minimizing adverse effects, representing an emerging frontier in metabolic therapeutics [3] [6].

The hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis represents a sophisticated regulatory system that maintains thyroid hormone homeostasis through integrated feedback mechanisms operating at multiple levels. The active thyroid hormone T3 serves as the primary determinant of basal metabolic rate through complex actions involving both central regulation in the hypothalamus and direct effects on peripheral tissues including liver, skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, and cardiovascular system. The continuing elucidation of thyroid hormone signaling pathways—from canonical genomic actions to rapid nongenomic effects—provides increasingly sophisticated insights into the molecular basis of metabolic regulation. Contemporary research approaches employing selective pharmacological agents, genetically modified animal models, and advanced metabolic phenotyping techniques continue to refine our understanding of thyroid physiology and identify novel therapeutic targets for metabolic disorders. As research progresses, the integration of thyroid hormone biology with systems physiology perspectives including microbiome interactions, immune regulation, and allostatic load will likely yield transformative insights into the role of the HPT axis in human health and disease.

The regulation of basal metabolic rate (BMR) is a complex process orchestrated by numerous hormonal signals, with thyroid hormones (THs), triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4), serving as primary determinants. While the endocrine system maintains circulating TH levels, their metabolic effects are ultimately determined by intracellular concentrations of bioactive T3 in peripheral tissues. This tissue-specific regulation is governed by two critical protein families: plasma membrane transporters, including monocarboxylate transporters (MCT8 and MCT10), and deiodinase enzymes (DIO1, DIO2, DIO3). These components collectively control the cellular uptake and activation of thyroid hormones, forming a crucial regulatory layer that modulates metabolic rate, thermogenesis, and energy expenditure [9] [10]. Understanding these mechanisms is paramount for developing targeted therapies for metabolic disorders, as fine-tuning thyroid hormone action at the tissue level could address pathologies like obesity and diabetes without disrupting systemic thyroid status [11] [10].

The coordinated action of transporters and deiodinases enables individual tissues to customize their metabolic response according to local physiological demands. This prereceptor regulation of thyroid hormone signaling represents a sophisticated mechanism that explains how tissues can exhibit different degrees of thyromimetic effects despite similar circulating hormone levels [12]. For researchers investigating BMR, this intricate regulatory system underscores the limitation of relying solely on serum thyroid profiles and emphasizes the need to assess tissue-specific thyroid status.

Thyroid Hormone Transporters: Gatekeepers of Cellular Access

For decades, the lipophilic nature of thyroid hormones led to the presumption that they passively diffused across plasma membranes. However, extensive research has established that carrier-mediated transport represents the primary mechanism for cellular thyroid hormone uptake [9]. This discovery revealed a previously unappreciated layer of regulation in thyroid hormone action, with several transporter families now recognized for their roles in this process.

Key Transporters and Their Characteristics

The monocarboxylate transporters MCT8 and MCT10, along with the organic anion-transporting polypeptide OATP1C1, represent the most specific and physiologically significant thyroid hormone transporters identified to date.

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Human Thyroid Hormone Transporters

| Gene | Transporter | Chromosome | Tissue Distribution | Substrate Preference | Functional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLC16A2 | MCT8 | Xq13.2 | Brain, liver, kidney, heart, thyroid | T4, T3, rT3 | Most specific TH transporter; mutations cause Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome |

| SLC16A10 | MCT10 | 16q21-q22 | Multiple tissues | T3 > T4 | Also transports aromatic amino acids; bidirectional transport |

| SLCO1C1 | OATP1C1 | 12p12 | Brain (astrocytes), testis | T4 > T3, rT3 | Almost exclusive T4 uptake in human brain astrocytes |

MCT8, encoded by the SLC16A2 gene on the X chromosome, exhibits high specificity for iodothyronines without transporting traditional monocarboxylates [9] [13]. The physiological criticality of MCT8 is dramatically illustrated in patients with Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome (AHDS), an X-linked disorder characterized by severe psychomotor retardation and abnormal thyroid hormone levels, resulting from mutations in the MCT8 gene [9] [14]. These patients present a unique thyroid profile with elevated serum T3, reduced T4, and normal or slightly elevated TSH, reflecting the complex role of MCT8 in both central and peripheral thyroid hormone homeostasis [15] [14].

MCT10 shares significant sequence homology with MCT8 (49% identity) but displays distinct functional characteristics [15]. While both transport thyroid hormones, MCT10 exhibits preferential transport of T3 over T4 and also functions as an aromatic amino acid transporter [9] [13]. Recent structural analyses reveal that despite their similarities, MCT8 and MCT10 exhibit distinct thyroid hormone recognition patterns that confer their substrate specificity [14].

OATP1C1 demonstrates a marked preference for T4 over T3 and is expressed almost exclusively in the brain and testis [9]. In human brain, OATP1C1 is predominantly localized to astrocytes rather than capillary endothelial cells, suggesting its primary role involves T4 uptake into astrocytes for subsequent conversion to T3 by type 2 deiodinase (DIO2) [9] [14]. This cellular compartmentalization highlights the sophisticated division of labor in cerebral thyroid hormone metabolism.

Structural Insights and Transport Mechanisms

Recent cryogenic-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) studies have provided unprecedented structural insights into thyroid hormone transport mechanisms. Both MCT8 and MCT10 belong to the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) and display the classical bilobed architecture consisting of N-terminal and C-terminal domains, each comprising six transmembrane helices [15] [14].

Table 2: Structural and Biophysical Properties of MCT8 and MCT10

| Parameter | MCT8 | MCT10 |

|---|---|---|

| Thyroxine (T4) Affinity (Kd) | 8.9 µM | 8.9 µM |

| Triiodothyronine (T3) Affinity (Kd) | 25.2 µM | 10.7 µM |

| TRIAC Affinity (Kd) | 20 µM | 19 µM |

| Silychristin Affinity (Kd) | 44.5-56.9 nM | >75 µM |

| Transport Mechanism | Facilitated diffusion | Facilitated diffusion |

Structural analyses of MCT8 in both outward-facing and inward-facing states have revealed a conserved network of gate residues involved in conformational changes triggered by thyroxine binding [15]. The T4 carboxylic group forms a salt bridge with Arg371 in MCT8 (Arg343 in MCT10), while the iodinated aromatic rings nestle within a highly hydrophobic pocket [15]. The transport cycle involves subtle conformational changes where transmembrane helix 7 kinks upon substrate binding, bringing Tyr339 closer to Asn119 on the opposite N-terminal domain and thereby occluding the gate [15].

The structural basis for inhibitor specificity has also been elucidated. The flavonolignan silychristin binds MCT8 with nanomolar affinity (Kd = 44.5-56.9 nM), locking it in an outward-facing state, while exhibiting minimal interaction with MCT10 (Kd > 75 µM) [15]. This specificity arises from distinct structural features in their substrate-binding pockets, providing a foundation for developing targeted therapeutic agents.

Deiodinases: Masters of Intracellular Thyroid Hormone Activation

Once inside cells, thyroid hormones undergo critical metabolic transformations catalyzed by the selenocysteine-containing deiodinase enzymes. This enzyme family precisely controls the activation and inactivation of thyroid hormones in a tissue-specific and developmentally regulated manner, serving as a crucial determinant of intracellular thyroid status [16] [12].

Deiodinase Types, Functions, and Distribution

The three deiodinase isoforms (DIO1, DIO2, DIO3) coordinate to maintain tissue-specific thyroid hormone homeostasis through their complementary actions on hormone activation and inactivation.

Table 3: Characteristics of Human Deiodinase Enzymes

| Enzyme | Gene | Primary Action | Cellular Location | Tissue Distribution | Kinetics | Sensitivity to PTU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIO1 | DIO1 | Activation & Inactivation | Plasma Membrane | Liver, kidney, thyroid | Ping-pong (Km µM) | High |

| DIO2 | DIO2 | Activation | Endoplasmic Reticulum | Brain, pituitary, brown fat, skeletal muscle | Sequential (Km nM) | Low |

| DIO3 | DIO3 | Inactivation | Plasma Membrane | Brain, placenta, skin, fetal tissues | Sequential (Km nM) | Low |

DIO1 exhibits both outer and inner ring deiodinase activity, enabling it to contribute to both T3 production (from T4) and hormone inactivation [16] [17]. It primarily generates T3 for export to plasma, with its activity in liver and kidney significantly contributing to circulating T3 levels [17]. DIO1 follows ping-pong kinetics and is highly sensitive to inhibition by propylthiouracil (PTU) [16].

DIO2 functions predominantly as an activating enzyme, converting T4 to T3 via outer ring deiodination [16] [12]. With a nanomolar Km for T4, DIO2 is optimized for efficient T3 production even at low substrate concentrations. Its location in the endoplasmic reticulum positions it ideally for providing T3 directly to the nucleus [16]. DIO2 is regulated at both transcriptional and posttranslational levels, with T4 inducing its degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway [16].

DIO3 exclusively catalyzes inner ring deiodination, inactivating both T4 and T3 to reverse T3 and T2, respectively [16] [17]. It is highly expressed in placental and fetal tissues, protecting developing tissues from excessive thyroid hormone exposure [12] [17]. Interestingly, DIO3 is rapidly internalized via endosomes and recycled back to the cell surface, suggesting its catalytic activity may occur in both extracellular and intracellular compartments [16].

Regulatory Mechanisms and Metabolic Significance

Deiodinase activities are dynamically regulated according to developmental stage, physiological demands, and pathological conditions. During critical periods such as fetal development, the coordinated expression of DIO2 and DIO3 ensures precise spatial and temporal control of thyroid hormone signaling [12]. In metabolic regulation, DIO2 plays a particularly important role in adaptive thermogenesis through its expression in brown adipose tissue (BAT) and skeletal muscle [10].

The deiodinases represent a dynamic system that permits tissues to customize their intracellular T3 concentration according to local physiological requirements, independently of circulating thyroid hormone levels [12]. This local control mechanism enables tissues to fine-tune their metabolic response to thyroid hormone without perturbing systemic homeostasis.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Cellular Transport Assays

Thyroid Hormone Uptake Measurements:

- Cell Culture: HeLa or other appropriate cell lines are cultured in standard DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum.

- Transporter Expression: Cells are transfected with plasmid DNA encoding the thyroid hormone transporter (MCT8, MCT10, or OATP1C1) using lipid-based transfection reagents. Empty vector serves as negative control.

- Transport Assay: 48 hours post-transfection, cells are incubated with radiolabeled [125I]-T4 or [125I]-T3 (specific activity: 4400 μCi/μg) in uptake buffer (e.g., Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution) for predetermined time points (typically 5-60 minutes).

- Inhibition Studies: To assess transporter specificity, parallel experiments are conducted with specific inhibitors (e.g., 100 μM silychristin for MCT8) or excess unlabeled substrate.

- Termination and Measurement: Uptake is terminated by rapid ice-cold wash buffer. Cells are lysed with 0.1N NaOH, and radioactivity is quantified using a gamma counter.

- Data Analysis: Specific transport is calculated by subtracting nonspecific uptake (vector control) from total uptake. Kinetic parameters (Km, Vmax) are determined through nonlinear regression analysis of concentration-dependent uptake [15] [14].

Deiodinase Activity Assays

Enzyme Kinetic Characterization:

- Tissue Preparation: Target tissues (liver for DIO1, brain for DIO2, placenta for DIO3) are homogenized in appropriate buffer (e.g., 0.25 M sucrose, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.0).

- Reaction Setup: Homogenates are incubated with radiolabeled substrate ([125I]-rT3 for DIO1, [125I]-T4 for DIO2/DIO3) in the presence of cofactors (5-20 mM dithiothreitol) and potential inhibitors (1 mM PTU for DIO1 specificity).

- Reaction Termination: After appropriate incubation time (30-60 minutes at 37°C), reactions are stopped by adding ice-cold ethanol.

- Product Separation: Deiodinated products are separated from substrate using HPLC or paper chromatography.

- Quantification: Radioactivity in product fractions is measured, and enzyme activity is calculated as pmol of substrate deiodinated per mg protein per minute [16] [17].

Structural Biology Approaches

Cryo-EM Structure Determination:

- Protein Engineering: MCT8 or OATP1C1 is engineered with N-terminal FLAG tag and C-terminal ALFA tag to facilitate purification and improve particle orientation.

- Expression and Purification: Proteins are overexpressed in HeLa cells, solubilized in detergent (e.g., glyco-diosgenin), and purified using anti-FLAG affinity chromatography.

- Complex Formation: Purified transporters are complexed with anti-ALFA nanobody and reconstituted in amphipols to improve stability and distribution.

- Grid Preparation: Samples are applied to cryo-EM grids, vitrified using liquid ethane, and screened for optimal ice thickness and particle distribution.

- Data Collection: High-resolution movies are collected using modern cryo-EM systems (e.g., Titan Krios) with dose-fractionation mode.

- Image Processing: Motion-corrected micrographs undergo particle picking, 2D classification, ab initio reconstruction, and nonuniform refinement to generate high-resolution density maps.

- Model Building: Atomic models are built and refined into cryo-EM maps using iterative cycles of manual building in Coot and refinement in Phenix [15] [14].

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Thyroid Hormone Transport and Metabolism Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | HeLa, HEK293, JEG-3 | Heterologous expression systems for transporter and deiodinase studies |

| Expression Vectors | pcDNA3.1, pEGFP vectors | Mammalian expression of tagged transporters (FLAG, ALFA tags) |

| Radiolabeled Compounds | [125I]-T4, [125I]-T3, [125I]-rT3 | Quantitative transport and enzyme activity measurements |

| Chemical Inhibitors | Silychristin (MCT8-specific), PTU (DIO1 inhibitor) | Mechanistic studies and pathway dissection |

| Antibodies | Anti-FLAG, Anti-HA, Na+/K+-ATPase | Protein detection, localization, and purification |

| Structural Biology Tools | Anti-ALFA nanobody, Amphipols | Cryo-EM sample preparation and structure determination |

| Analytical Instruments | Gamma counters, HPLC systems, Cryo-EM systems | Quantitative analysis and structural characterization |

Integrated Pathway and Experimental Workflow

Diagram 1: Integrated experimental workflow for studying thyroid hormone transporters and deiodinases, showing the parallel approaches in transport studies, structural biology, and enzyme characterization that converge to provide comprehensive mechanistic insights.

Diagram 2: Integrated pathway of thyroid hormone transport and metabolism, illustrating how transporters and deiodinases coordinate to regulate the cellular availability of active T3 for metabolic regulation.

The intricate interplay between thyroid hormone transporters and deiodinases represents a sophisticated regulatory system that tailors thyroid hormone action at the tissue level. This prereceptor control mechanism enables individual tissues to fine-tune their metabolic response according to local physiological demands, providing a crucial interface between systemic thyroid status and cellular metabolism. For researchers investigating basal metabolic rate, this system explains how tissues can exhibit varying degrees of metabolic responsiveness to similar circulating hormone levels and offers potential targets for metabolic interventions.

Recent structural breakthroughs in understanding MCT8 and OATP1C1 function provide unprecedented opportunities for rational drug design. The discovery of allosteric regulatory sites on these transporters, coupled with detailed mechanistic insights into deiodinase regulation, opens new avenues for developing tissue-selective thyroid hormone analogs and modulators. Future research directions should focus on elucidating the complete network of thyroid hormone transporters, understanding their regulation in metabolic diseases, and developing targeted therapies that can selectively modulate thyroid hormone action in specific tissues to optimize metabolic outcomes without disrupting systemic homeostasis.

Thyroid hormones (THs), primarily 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4), are essential regulators of development, growth, and metabolism in nearly all vertebrate tissues [18]. The genomic actions of thyroid hormones, classified as Type 1 signaling, are mediated by nuclear thyroid hormone receptors (TRs) that function as ligand-dependent transcription factors [18]. These receptors modulate transcription by binding to specific DNA sequences called thyroid hormone response elements (TREs) in the regulatory regions of target genes [19]. The intricate balance between thyroid hormone production, cellular uptake, receptor expression, and chromatin interactions constitutes a critical regulatory system that maintains metabolic homeostasis. Dysregulation of this pathway underpins several human diseases, including metabolic disorders, cardiovascular disease, and various cancers [18] [20]. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of thyroid hormone genomic signaling provides crucial insights into their fundamental role in regulating basal metabolic rate and energy expenditure, with significant implications for therapeutic development in metabolic diseases.

Thyroid Hormone Receptors (TRα and TRβ): Structure, Isoforms, and Localization

Receptor Subtypes and Structural Characteristics

The thyroid hormone receptors, TRα and TRβ, are members of the nuclear receptor superfamily encoded by separate genes: THRA (chromosome 17) and THRB (chromosome 3) in humans [21]. These genes generate multiple protein isoforms through alternative splicing, with TRα1, TRβ1, and TRβ2 representing the primary T3-binding variants [18] [21]. All functional TR isoforms share a conserved modular structure containing:

- DNA-binding domain (DBD): Highly conserved central domain featuring two zinc fingers that mediate sequence-specific recognition of and binding to TREs

- Ligand-binding domain (LBD): C-terminal domain that binds thyroid hormone with high affinity, with T3 binding TRs with approximately 10-fold higher affinity than T4 [20]

- Activation function domains: AF-1 domain in the N-terminal region and AF-2 domain within the LBD, which undergo conformational changes upon ligand binding to facilitate cofactor interactions [21]

Table 1: Major Thyroid Hormone Receptor Isoforms and Their Characteristics

| Isoform | Gene | Tissue Distribution | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRα1 | THRA | Heart, brain, bone, skeletal muscle | Cardiovascular function, neuronal development, skeletal maintenance |

| TRβ1 | THRB | Liver, kidney, brain | Hepatic lipid metabolism, cholesterol regulation, metabolic rate |

| TRβ2 | THRB | Pituitary gland, hypothalamus | Negative feedback in HPT axis, TSH regulation |

Subcellular Localization and Dynamics

Although primarily nuclear proteins, TRα1 and TRβ1 exhibit remarkable dynamism, shuttling rapidly between the nucleus and cytoplasm through specific nuclear localization signals (NLS) and nuclear export signals (NES) that interact with importins and exportins [18]. This continuous nucleocytoplasmic trafficking represents a critical control point for modulating thyroid hormone-responsive gene expression [18]. Recent research has also identified enigmatic cytoplasmic functions for certain TR variants and mitochondrial targeting sequences that expand the diversity of cellular responses to thyroid hormone [18]. The distribution of specific TR isoforms varies significantly between tissues and species, with TRα predominating in cardiovascular and central nervous systems, while TRβ is prevalent in metabolic tissues such as liver, contributing to the tissue-specific effects of thyroid hormones [21].

Thyroid Hormone Response Elements (TREs): Architecture and Recognition

Structural Diversity of TREs

Thyroid hormone response elements are specific DNA sequences located in the regulatory regions of target genes that serve as binding platforms for TRs. The canonical TRE consists of two core recognition motifs (typically AGGTCA or variants) arranged as direct repeats with a 4-base pair spacer (DR4) [22] [23]. However, natural TREs display considerable structural diversity, with variations in half-site sequence, orientation, and spacing contributing to functional specificity [19].

Table 2: Common Thyroid Hormone Response Element Configurations

| TRE Type | Arrangement | Core Sequence | Preference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Repeat (DR4) | AGGTCA(nnnn)AGGTCA | Direct repeat with 4bp spacer | Strong TR/RXR heterodimer binding |

| Palindromic (TREpal) | AGGTCATGACCT | Inverted palindrome | TR homodimer and heterodimer binding |

| Inverted Palindrome | TCAGGTCATGACCTGA | Inverted repeat with spacer | Variable TR/RXR binding |

| Single Half-site | (A/G)GGTCA | Single motif with flanking sequences | Often requires accessory factors |

TR-RXR Heterodimerization and Sequence-Specific Binding

TRs typically bind to TREs as heterodimers with retinoid X receptors (RXRs), with RXR occupying the upstream half-site in a typical DR4 arrangement [19] [24]. However, the requirement for RXR heterodimerization varies considerably depending on TRE sequence characteristics. When the upstream half-site contains TA or TG 5' to the core hexamer, TR homodimers can bind effectively with relative independence from RXR, while TREs with different upstream sequences show greater RXR dependence [19] [24]. This sequence-dependent variation in receptor binding requirements adds a significant layer of regulatory complexity to thyroid hormone signaling, allowing for fine-tuned gene-specific responses.

Mechanisms of Transcriptional Regulation

The Bimodal Switch Model and Beyond

The classical model of TR function depicts a bimodal switch where unliganded TR represses transcription through stable chromatin binding and recruitment of corepressor complexes, while hormone binding induces a conformational change that releases corepressors and recruits coactivators to activate transcription [23] [21]. However, recent genomic studies have revealed a more dynamic and nuanced picture:

- Ligand-dependent receptor recruitment: Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) studies demonstrate considerable hormone-induced TR recruitment to chromatin associated with chromatin remodeling and activated gene transcription, challenging the model of constitutive TR binding [23]

- Dynamic chromatin interactions: Genome-wide footprinting analyses provide little evidence for stable TR footprints both in the absence and presence of hormone, suggesting that TR engagement with chromatin is highly dynamic rather than static [23]

- Persistent binding sites: A significant subset of TRβ binding sites in pituitary chromatin maintains receptor occupancy regardless of T3 levels, and these sites show the most pronounced T3-dependent histone modifications and chromatin opening [22]

Chromatin Remodeling and Enhancer Activation

Thyroid hormone signaling induces significant chromatin remodeling at regulatory regions, as evidenced by genome-wide mapping of DNase I hypersensitive sites (DHS) and histone modifications. In liver tissue, T3 treatment results in thousands of regions with altered chromatin accessibility, with approximately 31% of differentially regulated DHSs being either formed or erased de novo as a consequence of T3 treatment [23]. These T3-remodelled regions are primarily located within intronic and intergenic regions and frequently correspond to active enhancers marked by increased H3K27 acetylation and H3K4 monomethylation [22]. Notably, T3 primarily increases rather than depletes these active histone marks at TR-bound distal sites, with minimal changes at promoter-proximal regions [22].

Diagram Title: TR Transcriptional Switch Mechanism

Experimental Analysis of Genomic Signaling

Key Methodologies and Workflows

Investigation of thyroid hormone genomic signaling employs sophisticated genomic and molecular biology techniques that have revealed the complex dynamics of TR-chromatin interactions:

- Chromatin Affinity Purification Sequencing (ChAP-seq): Using biotinylated TRβ expressed from the endogenous locus in mice, this approach identifies specific receptor binding sites in tissues such as pituitary and cerebral cortex with high specificity and low background [22]

- DNase I Hypersensitivity Sequencing (DNase-seq): Maps chromatin accessibility changes in response to T3 treatment, identifying thousands of regions with altered accessibility in liver tissue under hypothyroid versus hyperthyroid conditions [23]

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq): For endogenous TR and histone modifications (H3K27ac, H3K4me1), revealing hormone-dependent changes in enhancer activity and receptor occupancy [22] [23]

- Integrated genomic analysis: Combining TR binding data with chromatin accessibility and histone modification maps to define functional enhancers and their association with T3-regulated genes [22]

Diagram Title: Genomic Analysis Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Thyroid Hormone Genomic Signaling Studies

| Reagent/Cell System | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| ThrbHAB/HAB;Rosa26BirA/BirA mice | In vivo TRβ chromatin binding studies | Endogenously biotinylated TRβ for high-affinity purification; normal physiology |

| S. cerevisiae reporter system | TRE functional analysis | Lacks endogenous nuclear receptors; manipulable for TR/RXR expression |

| Anti-TRβ antibody (C1) | ChIP-seq against endogenous TR | Recognizes both TRβ and TRα; validated in TR double KO background |

| TR double knockout mice | Control for ChIP-seq specificity | Eliminates background from non-specific antibody binding |

| Methimazole (MMI)/PTU models | Established hypothyroid conditions | Blocks thyroid hormone synthesis; creates baseline for T3 responses |

| T3 treatment protocols | Hyperthyroid conditions | Acute or chronic T3 administration; reveals ligand-dependent effects |

Connection to Basal Metabolic Rate Regulation

The genomic actions of thyroid hormones through TRα and TRβ directly regulate basal metabolic rate (BMR) by controlling the expression of genes involved in mitochondrial biogenesis, thermogenesis, and substrate metabolism [20] [25]. Even within the euthyroid range, subtle variations in thyroid hormone levels associate with measurable differences in BMR, with free T3 showing a stronger correlation with metabolic rate than TSH or free T4 [25]. The TRβ isoform appears particularly important for metabolic regulation, as evidenced by the development of selective TRβ agonists that lower cholesterol and triglycerides without adverse cardiac effects [21]. Genomic studies reveal that TRβ binding sites in metabolic tissues are enriched near genes involved in hormonal responses and metabolic functions, providing a direct molecular link between receptor-chromatin interactions and metabolic control [22]. The poised receptor-enhancer complexes that maintain TR binding regardless of T3 levels may facilitate adjustable metabolic responses to fluctuating hormone levels, representing a genomic basis for metabolic adaptation [22].

The classical genomic actions of thyroid hormones (TH), primarily mediated by nuclear thyroid hormone receptors (TRs) that modulate gene transcription, have been well-established in the context of basal metabolic rate (BMR) regulation. However, emerging research has revealed that TH also initiates rapid signaling events through extranuclear pathways that significantly contribute to metabolic processes. These non-genomic actions occur too rapidly to involve changes in gene expression and are primarily initiated at the plasma membrane and within the cytoplasm [26]. The integral membrane protein integrin αvβ3 serves as a critical cell surface receptor for these non-genomic actions, recognizing both thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) with discrete affinities [27] [26]. This whitepaper examines the molecular mechanisms of integrin αvβ3-mediated thyroid hormone signaling and its implications for metabolic research and therapeutic development.

The significance of these non-genomic pathways extends to fundamental metabolic processes. While the genomic actions of TH primarily regulate long-term adaptive thermogenesis through nuclear receptor-mediated transcription, the non-genomic pathways contribute to more immediate metabolic responses [28] [26]. These rapid signaling events modulate cellular energy expenditure, mitochondrial function, and substrate utilization through mechanisms that operate independently of nuclear TR activation. Understanding these dual mechanisms provides a more comprehensive framework for investigating thyroid hormone regulation of basal metabolic rate and developing targeted therapeutic interventions for metabolic disorders.

Molecular Mechanisms of Integrin αvβ3-Mediated Thyroid Hormone Signaling

Receptor Recognition and Hormone Binding

Integrin αvβ3 possesses distinct binding sites for thyroid hormones on its extracellular domain [26]. The principal ligand for this receptor is L-thyroxine (T4), which binds at physiological concentrations, while T3 demonstrates approximately tenfold lower affinity and typically requires supraphysiological concentrations to initiate signaling [27]. The hormone recognition site overlaps with or is adjacent to the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) recognition sequence on the integrin, which explains why RGD peptides can effectively block thyroid hormone binding and subsequent ERK1/2 activation [27]. This receptor is highly expressed in rapidly dividing cell types, including tumor cells and proliferating endothelial cells, but is present at lower levels in normal, non-malignant cells [29].

Following hormone binding, integrin αvβ3 undergoes conformational changes that trigger its internalization through caveolin-dependent mechanisms [27]. During this process, the integrin heterodimer disassociates, allowing the monomeric αv subunit—but not β3—to translocate to the nucleus in complex with phosphorylated ERK1/2 [27]. This complex then associates with transcriptional coactivators (p300, STAT1) and corepressors (NCoR, SMRT) to regulate gene expression through a non-classical mechanism that does not involve direct thyroid hormone receptor binding to DNA [27].

Downstream Signal Transduction Pathways

The binding of thyroid hormones to integrin αvβ3 activates several key intracellular signaling cascades that mediate the hormone's rapid effects. The table below summarizes the primary signaling pathways and their functional consequences in target cells:

Table 1: Key Signaling Pathways Activated by Thyroid Hormone Binding to Integrin αvβ3

| Signaling Pathway | Key Components | Biological Consequences | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERK1/2 Pathway | ERK1/2, FAK, Src | Cell proliferation, gene expression regulation, dendritogenesis | Cancer cell proliferation, neuronal development [27] [30] |

| PI3K/Akt Pathway | PI3K, Akt, mTOR | Anti-apoptosis, cell survival, metabolic regulation | Cancer cell survival, radioresistance [31] [32] |

| Cytoskeletal Regulation | F-actin, p190 RhoGEF | Actin reorganization, neurite outgrowth, cell migration | Neuronal development, brain morphogenesis [30] [26] |

The extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) pathway represents a major signaling route initiated by thyroid hormone binding to integrin αvβ3 [27]. Activation occurs through focal adhesion kinase (FAK), a non-receptor tyrosine kinase that connects integrin activation to downstream signaling events [27] [30]. Phosphorylated ERK1/2 then translocates to the nucleus where it modulates transcriptional activity through phosphorylation of coactivators and corepressors [27]. In cancer models, this pathway promotes cell proliferation and contributes to chemoresistance, particularly in colorectal carcinoma with Ras mutations [27].

The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway represents another critical signaling route, though interestingly, T3 appears to be more effective than T4 in activating this particular pathway [27]. PI3K activation leads to Akt phosphorylation, which subsequently promotes cell survival through inhibition of apoptotic mechanisms [32]. This pathway contributes to the anti-apoptotic effects of thyroid hormone in various cancer models and supports tumor cell survival under stress conditions.

Additionally, thyroid hormone binding to integrin αvβ3 regulates the state of the actin cytoskeleton through rapid mechanisms that involve both T4 and reverse T3 (rT3), but not T3 [26]. This action is particularly important in neural cells, where adequate polymerization of actin (F-actin) is essential for normal dendritogenesis and neurite outgrowth during development [30] [26]. The cytoskeletal effects manifest within minutes of hormone exposure and do not require changes in actin mRNA abundance, confirming their non-genomic nature [26].

Quantitative Data and Experimental Findings

Research across multiple model systems has generated quantitative data characterizing the molecular and cellular consequences of thyroid hormone signaling through integrin αvβ3. The following table summarizes key experimental findings from recent studies:

Table 2: Quantitative Experimental Findings in Integrin αvβ3-Mediated Thyroid Hormone Signaling

| Experimental System | Hormone Concentration | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebellar Purkinje Cells | 10 nM T3, T4, or rT3 | Significant augmentation of dendrite arborization; suppressed by LM609 (integrin αvβ3 antagonist) and TR knockdown | [30] |

| Neuro-2A Clonal Cells | 10 nM T3, T4, or rT3 | Induction of neurite growth; reduced by LM609 and TRα knockdown; increased phosphorylation of FAK, Akt, ERK1/2 | [30] |

| T-cell Lymphoma Models | Physiological concentrations | Promoted TCL proliferation and VEGF-driven angiogenesis; inhibition of integrin αvβ3 decreased tumor growth and angiogenesis | [32] |

| Colorectal Cancer Cells | Physiological T4 | Induced proliferation via ERK1/2; tetrac and NDAT blocked proliferation and overcome chemoresistance in Ras-mutant cells | [27] |

| Various Cancer Cell Lines | Physiological T4 | Stimulation of tumor cell proliferation, anti-apoptosis, radioresistance; differential regulation of specific genes | [26] [29] |

These quantitative findings demonstrate that thyroid hormones at physiological concentrations (typically 10 nM in experimental systems) can elicit significant cellular responses through integrin αvβ3-mediated signaling. The effects are consistently observed across diverse cell types, including neurons, immune cells, and various cancer models, highlighting the broad relevance of this pathway.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Investigating Integrin αvβ3-Mediated Neuritogenesis

The role of integrin αvβ3 in thyroid hormone-induced neuritogenesis has been systematically investigated using primary cerebellar cultures and neuronal cell lines [30]. The following protocol represents a standardized approach for assessing these effects:

Cell Culture Preparation:

- Primary cerebellar cultures are prepared from postnatal day 0 C57BL/6 mice through enzymatic digestion with papain dilution buffer (0.2 unit/mL papain, 0.02 mg/mL DNase I, 0.2 mg/mL L-cysteine, 5 mg/mL glucose, and 0.2 mg/mL bovine serum albumin in PBS) [30].

- Dissociated cells are resuspended in cerebellar culture medium (DMEM/F12 containing 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 3.9 mM glutamine, 2.1 mg/mL glucose, 30 nM sodium selenite, 20 μg/mL insulin, and 200 μg/mL transferrin) [30].

- Cells are plated at a density of 3×10^5 cells/0.3 mL in poly-L-lysine-coated chamber slides and maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

Hormone Treatment and Pharmacological Inhibition:

- At 16-24 hours after plating, thyroid hormones (T3, T4, or rT3) are added to the culture medium at a concentration of 10 nM [30].

- For inhibition studies, the integrin αvβ3 antagonist LM609 (monoclonal antibody) is applied concurrently with hormone treatment.

- For gene knockdown approaches, TRα and TRβ expression is reduced using specific siRNAs or shRNAs to distinguish receptor-dependent and independent effects.

Assessment and Analysis:

- After 17 days in culture, cells are fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and processed for immunohistochemistry [30].

- Dendritic arborization and neurite outgrowth are quantified using morphological analysis with specific markers for neuronal cells (e.g., calbindin for Purkinje cells).

- Phosphorylation of signaling components (FAK, Akt, ERK1/2) is assessed by Western blotting or immunocytochemistry.

- Actin cytoskeleton reorganization is evaluated using F-actin staining with phalloidin conjugates, and synapsin-1 localization is examined as a marker of synaptic differentiation.

Evaluating Cancer Cell Proliferation and Signaling

The proliferative effects of thyroid hormone via integrin αvβ3 have been extensively characterized in cancer models using the following methodological approach:

Cell Culture and Treatment:

- Human cancer cell lines (e.g., breast cancer, colorectal cancer, glioblastoma) are maintained in appropriate culture media [27] [29].

- Cells are treated with physiological concentrations of T4 (0.1-10 nM) or T3 (1-100 nM) for varying time periods (minutes to days) to assess both rapid signaling and long-term proliferation [27].

- For antagonist studies, tetraiodothyroacetic acid (tetrac) or its nanoparticle derivative (NDAT) is applied at concentrations ranging from 1-10 μM to block the hormone-integrin interaction [27].

Signal Transduction Analysis:

- Following hormone treatment (typically 5-30 minutes for initial signaling events), cells are lysed and protein extracts are analyzed by Western blotting for phosphorylated ERK1/2, FAK, and Akt [27] [30].

- Integrin internalization is tracked using fluorescently labeled antibodies or integrin-GFP constructs through live-cell imaging and immunofluorescence [27].

- Gene expression changes are assessed by RT-PCR or RNA sequencing for known target genes such as HIF-1α, COX-2, and ER-α [27].

Functional Assays:

- Cell proliferation is quantified using MTT assays, BrdU incorporation, or direct cell counting over 3-7 days [27] [29].

- Apoptosis resistance is evaluated through Annexin V staining and caspase activity assays in the presence of chemotherapeutic agents [32].

- Angiogenic potential is assessed by measuring VEGF production (ELISA) and in vitro tube formation assays using endothelial cells [32].

Visualization of Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the key molecular events in integrin αvβ3-mediated thyroid hormone signaling, created using Graphviz DOT language with specified color palette compliance.

Diagram 1: Integrin αvβ3-mediated thyroid hormone signaling pathway

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for investigating non-genomic TH actions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table compiles key reagents and their applications for investigating integrin αvβ3-mediated thyroid hormone signaling:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Integrin αvβ3-Mediated Thyroid Hormone Signaling

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hormone Preparations | T4 (Thyroxine), T3 (Triiodothyronine), rT3 (Reverse T3) | Control treatments; concentration-response studies | Natural ligands with differential affinity for integrin αvβ3 [27] [30] |

| Receptor Antagonists | Tetrac (Tetraiodothyroacetic acid), NDAT (Nanoparticle-conjugated Tetrac) | Block specific hormone-integrin interaction; cancer therapeutic studies | Competes with thyroid hormones for integrin binding site [27] [29] |

| Integrin Inhibitors | LM609 (monoclonal antibody), RGD peptides, Cilengitide | Specific blockade of integrin αvβ3 function | Binds extracellular domain preventing ligand interaction [27] [30] |

| Signaling Inhibitors | FAK inhibitors (PF-573228), MEK/ERK inhibitors (U0126), PI3K inhibitors (LY294002) | Pathway dissection; determination of signaling mechanisms | Blocks specific kinase activities in downstream pathways [27] [30] |

| Molecular Biology Tools | siRNAs against TRα, TRβ, integrin subunits; Plasmid constructs | Gene function studies; receptor dependence assessment | Selective knockdown or overexpression of target genes [30] |

| Detection Reagents | Phospho-specific antibodies (pERK, pAkt, pFAK), F-actin probes (Phalloidin) | Signal transduction monitoring; cytoskeletal changes | Visualizes and quantifies pathway activation and morphological effects [30] |

These research tools enable comprehensive investigation of the molecular mechanisms underlying integrin αvβ3-mediated thyroid hormone signaling. The availability of specific antagonists like tetrac and NDAT provides particularly valuable approaches for discriminating between genomic and non-genomic actions of thyroid hormones [27] [29].

The recognition of integrin αvβ3 as a functional receptor for thyroid hormones has substantially expanded our understanding of thyroid hormone action beyond classical genomic mechanisms. These non-genomic pathways mediate rapid signaling events that contribute to fundamental cellular processes including proliferation, survival, metabolism, and development. The implications for basal metabolic rate research are particularly significant, as these rapid mechanisms may work in concert with genomic actions to fine-tune metabolic regulation.

From a therapeutic perspective, the integrin αvβ3 receptor represents a promising target for drug development, particularly in oncology where thyroid hormone signaling promotes tumor progression and chemoresistance [27] [29]. Tetrac-based therapeutics that specifically target the hormone-integrin interaction offer a novel approach for disrupting these pathways without affecting genomic thyroid hormone functions. Further research elucidating the crosstalk between integrin-mediated signaling and traditional nuclear pathways will continue to enhance our understanding of thyroid hormone physiology and its relationship to metabolic regulation in health and disease.

Thyroid hormones, triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4), are principal regulators of energy homeostasis and basal metabolic rate (BMR). They exert profound direct metabolic effects by modulating fundamental cellular processes, including mitochondrial biogenesis, oxidative phosphorylation, and ion gradient maintenance. This review details the molecular mechanisms through which T3 and T3 regulate mitochondrial mass and function and control the activity of Na+/K+ ATPase, the major energy-consuming process in cells. Understanding these pathways is critical for research and drug development targeting metabolic diseases, aging, and endocrine disorders.

Regulation of Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Respiration

Transcriptional Control of Mitochondrial Biogenesis

Mitochondrial biogenesis is the growth and division of pre-existing mitochondria, a process requiring coordinated expression of both nuclear and mitochondrial genomes [33]. Thyroid hormones are master regulators of this process, primarily through the activation of a well-defined transcriptional cascade.

- Master Regulator PGC-1α: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) is the central regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis [33] [34]. It acts as a co-transcriptional regulator, interacting with and co-activating multiple transcription factors.

- Nuclear Respiratory Factors (NRFs): PGC-1α activates nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF-1) and NRF-2 [33] [35]. These transcription factors control the expression of nuclear genes encoding all electron transport chain (ETC) subunits and key factors for mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) transcription and replication [35].

- Mitochondrial Transcription Factor A (TFAM): NRF-1 directly activates the expression of TFAM, the final effector that drives mtDNA transcription and replication [35] [34]. Increased TFAM is a hallmark of mitochondrial biogenesis.

Table 1: Key Proteins in the Mitochondrial Biogenesis Transcriptional Cascade

| Protein | Function | Role in Biogenesis |

|---|---|---|

| PGC-1α | Transcriptional coactivator | Master regulator; integrates signaling pathways and activates NRFs [33] [34] |

| NRF-1 | Transcription factor | Activates expression of ETC genes, TFAM, TFB1M, and TFB2M [35] |

| NRF-2 (GABPA) | Transcription factor | Regulates expression of nuclear-encoded ETC subunits and TOMM20 [35] |

| TFAM | mtDNA binding protein | Essential for mtDNA transcription and replication; packages mtDNA [35] [34] |

Thyroid Hormone Signaling to Mitochondrial Biogenesis

Thyroid hormones stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis primarily by upregulating the expression and activity of PGC-1α [2]. The interaction between T3 and its nuclear receptors leads to the activation of the PGC-1α cascade, resulting in an increased number of mitochondria and elevated oxidative phosphorylation capacity [34]. This direct genomic action is a key mechanism for increasing the cell's capacity for ATP production and overall metabolic rate.

Upstream Signaling Pathways

Several upstream signaling pathways converge on PGC-1α to regulate mitochondrial biogenesis in response to energy demand and cellular stress.

- AMPK Pathway: AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) acts as a cellular energy sensor. Upon activation by an increased AMP/ATP ratio, it directly phosphorylates and activates PGC-1α [33]. Chronic AMPK activation upregulates PGC-1α expression and induces mitochondrial biogenesis [33].

- CaMK Pathway: An increase in intracellular Ca²⁺ activates Ca²+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK), which in turn activates PGC-1α expression via the transcription factor CREB [35].

- p38 MAPK Pathway: The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) regulates PGC-1α both by activating its transcription (via MEF2 and ATF2) and through post-translational phosphorylation that enhances its activity [35].

- Sirtuins and cGMP: SIRT1 deacetylates and activates PGC-1α [35]. Nitric oxide (NO) production leads to increased cGMP, which also promotes mitochondrial biogenesis [35].

The following diagram illustrates the core transcriptional cascade and the key upstream signaling pathways that regulate mitochondrial biogenesis.

Quantitative Effects on Respiration and Metabolic Rate

Thyroid hormones significantly increase cellular oxygen consumption and basal metabolic rate. This is quantitatively demonstrated through metabolic flux analyses.

- Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR): Studies using Seahorse metabolic flux analyzers show that cellular models with impaired thyroid-hormone-like signaling (e.g., loss of Na/K-ATPase α1/Src interaction) exhibit significantly reduced basal and maximal OCR, along with a ~65% reduction in spare respiratory capacity [36].

- In Vivo Correlations: In free-ranging birds, circulating T3 levels positively correlate with resting metabolic rate (RMR), establishing a direct link between thyroid hormone levels and whole-animal energy expenditure [37].

Table 2: Quantitative Metabolic Parameters Influenced by Thyroid Hormone Signaling

| Metabolic Parameter | Measurement Technique | Effect of Enhanced Thyroid Hormone Signaling |

|---|---|---|

| Basal Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR) | Seahorse Mitochondrial Stress Test | Increased [36] |

| Maximal OCR | Seahorse Mitochondrial Stress Test | Increased [36] |

| Spare Respiratory Capacity | Seahorse Mitochondrial Stress Test | Increased (~65% higher in functional models) [36] |

| Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR) | Respirometry (whole organism) | Positively correlated with T3 levels [37] |

Regulation of Na+/K+ ATPase Activity

Mechanism of Na+/K+ ATPase Stimulation by Thyroid Hormone

The Na+/K+ ATPase is a critical P-type ATPase that maintains transmembrane Na+ and K+ gradients, consuming a substantial portion of cellular ATP. Thyroid hormones directly and rapidly stimulate its activity.

- Stimulation of Activity: Physiological concentrations of T3 (as low as 10⁻⁹ M) significantly increase the hydrolytic activity of Na+/K+ ATPase in alveolar epithelial cells, with peak effects (up to 2-fold increase) observed within hours [38].

- Non-Transcriptional Mechanism: This stimulation is T3-specific (reverse T3 has no effect) and is not blocked by the transcription inhibitor actinomycin D. No changes in Na+/K+ ATPase mRNA or total protein levels are detected, ruling out a genomic mechanism in the short term [38].

- Membrane Insertion: The upregulation occurs via translocation of existing Na+/K+ ATPase α1- and β1-subunit proteins to the plasma membrane. This process is abolished by brefeldin A, an inhibitor of protein trafficking from the Golgi apparatus [38].

Signaling and Redox Regulation of Na+/K+ ATPase

Beyond direct hormonal control, Na+/K+ ATPase activity is finely tuned by redox-sensitive mechanisms, allowing it to function as an "oxygen sensor" and adjust its ATP consumption to metabolic supply [39].

- Redox-Sensitive Thiols: Regulatory thiol groups on all three subunits of the Na+/K+ ATPase are targets for reversible modifications, including S-glutathionylation and S-nitrosylation, which directly modulate pump activity [39].

- ROS and RNS as Messengers: Reactive oxygen species (ROS) like H₂O₂ and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) like nitric oxide (NO) act as signaling messengers that modify these thiols, adjusting pump activity to cellular metabolic conditions, particularly during hypoxia [39].

- Signaling Platform: The Na+/K+ ATPase, especially the α1 isoform, also serves as a signaling scaffold. Its interaction with Src kinase regulates processes like metabolic reserve and flexibility. Disruption of this interaction in cell models leads to a complete loss of metabolic reserve and increased reliance on glycolysis [36].

The diagram below integrates the rapid, non-genomic stimulation of the Na+/K+ ATPase by T3 with the redox-sensitive regulatory network that allows it to adapt to the cell's metabolic state.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Experimental Reagents & Methodologies

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Investigating Thyroid Metabolic Effects

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Use in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Seahorse XF Analyzer | Real-time measurement of OCR and ECAR in live cells. | Quantifying mitochondrial function (basal/maximal respiration, spare capacity) and glycolytic rate in response to T3/T4 [36]. |

| 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose (2-DG) | Competitive glycolytic inhibitor. | Assessing metabolic flexibility and reliance on glycolysis in cell models [36]. |

| pNaKtide | Cell-permeable peptide inhibitor of NKA α1/Src interaction. | Probing the role of NKA α1-specific signaling in metabolic regulation and insulin resistance [36]. |

| AICAR | AMPK agonist. | Experimentally activating the AMPK pathway to study its role in PGC-1α activation and mitochondrial biogenesis [33]. |

| Brefeldin A | Inhibitor of protein transport from Golgi. | Differentiating between transcriptional and post-translational (e.g., membrane insertion) mechanisms, as used in T3-Na+/K+ ATPase studies [38]. |