Rebound Hyperglycemia and the Somogyi Effect: Evidence, Mechanisms, and Modern Clinical Management

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of rebound hyperglycemia following hypoglycemia, critically examining the scientific validity of the Somogyi effect in light of contemporary evidence.

Rebound Hyperglycemia and the Somogyi Effect: Evidence, Mechanisms, and Modern Clinical Management

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of rebound hyperglycemia following hypoglycemia, critically examining the scientific validity of the Somogyi effect in light of contemporary evidence. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational pathophysiology with advanced methodological approaches for investigation and mitigation. The scope encompasses the evolution of the Somogyi theory, the application of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) for objective quantification, strategies for troubleshooting glycemic instability, and a comparative validation of this phenomenon against the more prevalent dawn phenomenon. The discussion is grounded in recent large-scale clinical studies and technological advancements, offering insights for future therapeutic innovation and clinical practice guidelines.

The Somogyi Effect: Foundational Concepts and Evolving Scientific Understanding

Historical Context and Original Postulates of the Somogyi Phenomenon

FAQ: What is the Somogyi Phenomenon?

Q: What did Michael Somogyi originally postulate? A: In the 1930s, Dr. Michael Somogyi, a Hungarian-born biochemist, postulated the phenomenon of "rebound hyperglycemia" [1] [2]. He theorized that an overdose of insulin could induce hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) during the late evening or night [1] [3]. This hypoglycemic episode would then trigger a defensive counter-regulatory hormonal response, involving hormones like glucagon, adrenaline, cortisol, and growth hormone [1] [2]. These hormones stimulate the liver to produce and release large amounts of glucose, leading to paradoxical hyperglycemia (high blood sugar) by the next morning [4] [3]. For decades, this theory, known as the Somogyi effect or Somogyi hypothesis, was an axiom in diabetes treatment [5] [6].

Q: How does the Somogyi effect differ from the Dawn Phenomenon? A: Both can cause high morning blood sugar, but their proposed mechanisms are fundamentally different. The table below summarizes the key distinctions.

Table 1: Distinguishing the Somogyi Effect from the Dawn Phenomenon

| Feature | Somogyi Phenomenon | Dawn Phenomenon |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Cause | Rebound effect from nocturnal hypoglycemia [1] [3] | Natural early-morning release of insulin-antagonist hormones (e.g., growth hormone, cortisol) [1] [2] |

| Nocturnal Hypoglycemia | Present; considered the trigger [4] | Absent [1] [3] |

| Prevalence | Considered rare or debated [1] [2] [7] | More common [1] [2] |

| Theoretical Basis | A theory, with current evidence disputing its prevalence [1] [3] [7] | A well-accepted physiological occurrence [1] |

FAQ: What is the Historical and Scientific Context of Dr. Somogyi's Work?

Q: Who was Dr. Michael Somogyi? A: Michael Somogyi (1883-1971) was a Hungarian biochemist who pursued his scientific career primarily in the United States [5] [6]. He was a pioneer in the field of diabetes, involved in devising one of the first methods for insulin extraction and was part of the team that treated the first child with diabetes using insulin in the United States in 1922 [5] [6]. His personal experiences with food scarcity during his youth and World War I shaped his interest in the effects of diet on metabolic disorders [5] [6]. He was also a translational researcher who standardized numerous clinical laboratory determinations, most famously the method for measuring amylase, with results reported in "Somogyi units" for decades [5] [6].

Q: What is the modern scientific view on the Somogyi phenomenon? A: The Somogyi phenomenon is a subject of ongoing debate and is no longer considered a common cause of morning hyperglycemia [1] [3] [2]. More recent studies using continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) have challenged its validity [1] [3]. Several studies have concluded that nocturnal hypoglycemia does not commonly result in major morning hyperglycemia and that high fasting glucose is more likely a sign of insufficient insulin (hypoinsulinemia) or waning of the insulin dose overnight, rather than a rebound effect [1] [2] [7]. Some researchers have suggested that apparent rebound hyperglycemia may instead be caused by insulin-induced insulin resistance [2].

Researcher's Toolkit: Experimental Protocols & Reagents

This section provides methodologies and materials for investigating mechanisms of morning hyperglycemia.

Experimental Protocol: Investigating Nocturnal Glycemic Control

Aim: To determine the cause of persistent fasting hyperglycemia in a subject, differentiating between the Somogyi effect, the dawn phenomenon, and simple insulin deficiency.

Materials:

- Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) system [1] [2] or

- Blood glucose meter and test strips for manual monitoring

- Logbook for recording food intake, insulin doses, and exercise

Method:

- For CGM-based profiling: Deploy a CGM system to capture interstitial glucose readings continuously every few minutes throughout the night and early morning. Data should be collected over several nights to establish a pattern [1] [2].

- For manual profiling: Instruct the subject to measure blood glucose at the following times for at least two consecutive nights [3]:

- Two hours after the evening meal

- At bedtime (e.g., 10:00 PM)

- Between 2:00 AM and 3:00 AM (nocturnal nadir)

- Immediately upon waking (e.g., 6:00 AM - 7:00 AM)

- Correlate glucose measurements with records of evening food intake, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and insulin administration to identify potential triggers [4].

Data Interpretation:

- Pattern A (Somogyi Effect): Blood glucose is low (e.g., <70 mg/dL or <4 mmol/L) at 3:00 AM but high upon waking [4] [3].

- Pattern B (Dawn Phenomenon): Blood glucose is stable and within range at 3:00 AM but begins to rise significantly in the pre-dawn hours until waking [1].

- Pattern C (Waning Insulin/Insulin Deficiency): Blood glucose is elevated at bedtime and remains high or continues to rise steadily throughout the night [1] [2] [7].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Investigating Glucose Counter-Regulation

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Investigation |

|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) | Provides high-frequency, temporal data on glucose levels to identify nocturnal hypoglycemic episodes and morning rise patterns without disrupting sleep [1] [2]. |

| Insulin (various formulations) | To manipulate nocturnal insulin levels and study the effects of insulin overdose, type, and timing on morning glucose homeostasis [5] [2]. |

| Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Kits | For quantitative measurement of counter-regulatory hormones in plasma/serum (e.g., Glucagon, Cortisol, Growth Hormone, Epinephrine) to confirm their activation post-hypoglycemia [1] [8]. |

| Radioimmunoassay (RIA) Kits | A traditional method for precise measurement of hormone levels, including insulin and C-peptide, to assess endogenous insulin secretion and insulin resistance [8]. |

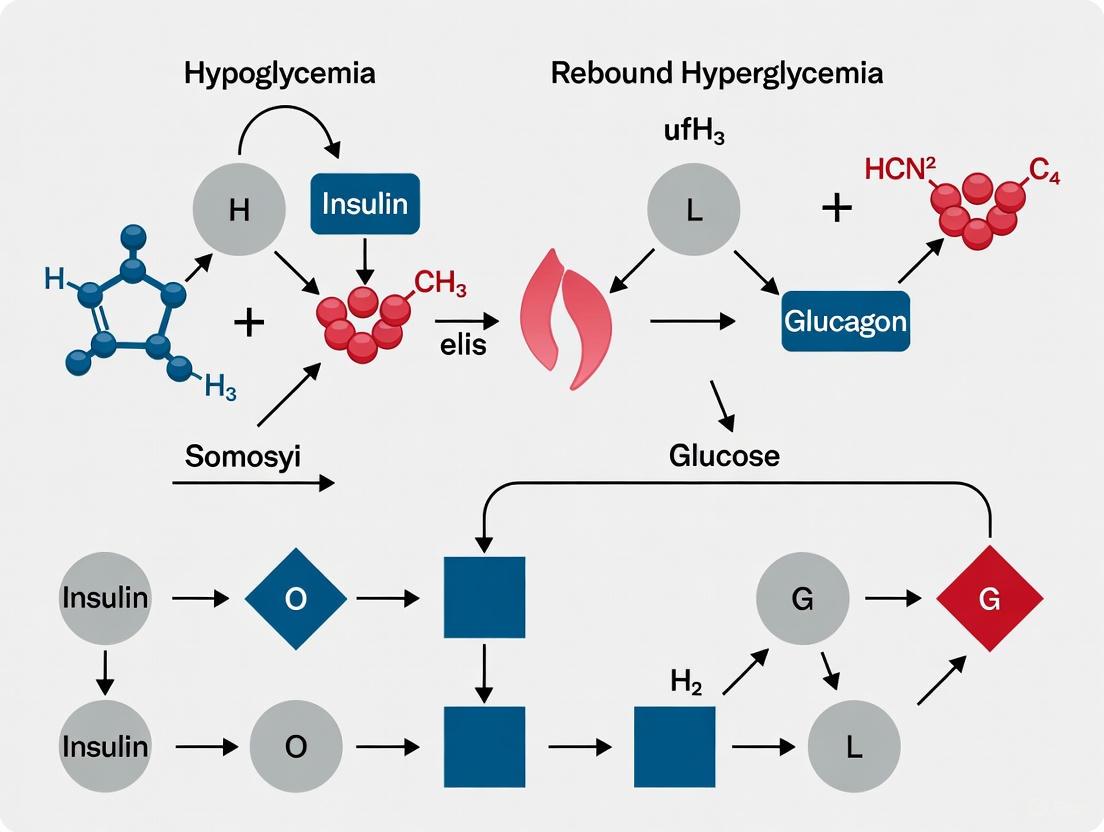

Visualization: The Hypothesized Pathway of the Somogyi Effect

The following diagram illustrates the sequence of physiological events as originally postulated by Michael Somogyi, from the initial insulin administration to the final rebound hyperglycemia.

Diagram 1: The postulated pathway of the Somogyi effect, illustrating the sequence of physiological events from the initial insulin administration to the final rebound hyperglycemia.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is a counterregulatory hormone surge in the context of hypoglycemia? A counterregulatory hormone surge describes the body's physiological defense mechanism against falling blood glucose levels. When hypoglycemia occurs, the body releases several hormones—primarily glucagon, epinephrine, cortisol, and growth hormone—that oppose the action of insulin [9] [2] [10]. These hormones work to raise blood glucose by stimulating glycogenolysis (breakdown of glycogen) and gluconeogenesis (production of new glucose), thereby counteracting the hypoglycemic state [1] [10].

2. What is the Somogyi effect, and what is its current scientific standing? The Somogyi effect is a theory proposing that nocturnal hypoglycemia can trigger a counterregulatory hormone surge, leading to rebound hyperglycemia in the morning [1] [3]. However, its validity is debated in the scientific community. Recent studies using continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) have challenged this theory, showing that nocturnal hypoglycemia often leads to normal or low fasting glucose, not hyperglycemia [1] [2]. Many experts now consider the dawn phenomenon—a natural early morning rise in blood sugar due to hormonal changes—a more common cause of morning hyperglycemia [1] [3].

3. How do counterregulatory hormones mechanistically regulate gluconeogenesis? Counterregulatory hormones regulate gluconeogenesis through rapid hormonal signaling and allosteric modulation of key enzymes.

- Glucagon: Binds to G-protein-coupled receptors, activating protein kinase A (PKA). PKA phosphorylates and inactivates pyruvate kinase, while also reducing levels of fructose-2,6-bisphosphate, a potent inhibitor of gluconeogenesis. This simultaneously halts glycolysis and promotes gluconeogenic flux [11].

- Epinephrine: Acts via beta-adrenergic receptors to stimulate glycogenolysis for immediate glucose release, and provides gluconeogenic precursors by mobilizing lactate and alanine from muscle and glycerol from adipose tissue [9] [12].

- Cortisol and Growth Hormone: These hormones promote insulin resistance in peripheral tissues over several hours, reducing glucose utilization and making more glucose available [9] [13].

4. What are the key experimental considerations for modeling the Somogyi effect in a research setting? Researchers should consider several factors and use appropriate controls to distinguish the Somogyi effect from other phenomena.

- Temporal Monitoring: It is crucial to measure blood glucose concentrations at multiple time points: after an evening meal, at bedtime, in the middle of the night (e.g., 3 AM), and upon waking [3].

- Hormone Assays: Confirm the counterregulatory surge by directly measuring plasma or urinary levels of glucagon, cortisol, epinephrine, and growth hormone [13].

- Control for Dawn Phenomenon: The dawn phenomenon also causes morning hyperglycemia but is not preceded by hypoglycemia. Including a control group or condition without induced hypoglycemia is essential for differentiation [1] [2].

- Subject Selection: The model system (e.g., animal model vs. human patients) and their insulin secretory status (e.g., C-peptide positive vs. negative) can significantly impact results, as endogenous insulin secretion influences counterregulatory responses [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Investigating Unanticipated Morning Hyperglycemia in a Diabetic Research Model

Problem: Consistent, unexplained morning hyperglycemia is observed in a research model, complicating data interpretation in a study of glycemic control.

Solution: A systematic approach is required to identify the root cause.

Step 1: Differentiate Between Somogyi Effect and Dawn Phenomenon

- Action: Implement frequent nocturnal blood glucose monitoring, ideally using a continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) system [2] [3].

- Interpretation: If a hypoglycemic episode (glucose <70 mg/dL or 3.9 mmol/L) is followed by hyperglycemia, it may indicate a Somogyi-like rebound. If glucose levels are stable or steadily rise from ~3 AM onward without preceding hypoglycemia, it is likely the dawn phenomenon [1].

Step 2: Evaluate the Insulin Regimen

- Action: Audit the timing and dosage of insulin administration. An excessive dose of intermediate- or long-acting insulin in the evening is a common cause of nocturnal hypoglycemia [2].

- Interpretation: If nocturnal hypoglycemia is confirmed, the solution is often a reduction in the evening insulin dose or a change to a different insulin formulation, not an increase [2] [3].

Step 3: Assess for Hypoglycemia Unawareness

Guide 2: Inconsistent Gluconeogenesis Flux Measurements in a Hepatic Cell Model

Problem: Measurements of gluconeogenic flux in hepatocyte cultures are highly variable following the application of counterregulatory hormones.

Solution: Inconsistency often stems from unregulated variables in the cellular environment.

Step 1: Verify Substrate Availability

- Action: Ensure the culture media contains an adequate and consistent supply of gluconeogenic precursors such as lactate, pyruvate, alanine, and glycerol [11].

- Interpretation: Gluconeogenesis cannot proceed optimally without sufficient substrates. Inconsistent results may be due to depletion of these compounds.

Step 2: Monitor Cellular Energy Status

- Action: Assess the ATP/ADP and ATP/AMP ratios in cell lysates. Gluconeogenesis is an energy-intensive process that requires high ATP levels [11].

- Interpretation: Low energy charge (high ADP/ATP or AMP/ATP) will inhibit key enzymes like fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase, leading to reduced and variable flux [14] [11] [15].

Step 3: Control for Allosteric Effectors

- Action: Check for the presence and concentration of key allosteric regulators.

- Interpretation:

- Acetyl-CoA: This is a potent allosteric activator of pyruvate carboxylase, the first committed step in gluconeogenesis. Its levels must be sufficient to initiate the pathway [14] [11].

- Fructose-2,6-bisphosphate: This metabolite is a powerful allosteric inhibitor of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase. Hormones like glucagon lower its concentration to de-repress gluconeogenesis [14] [11].

The tables below consolidate key quantitative findings on hypoglycemia thresholds and counterregulatory hormone activity for easy reference.

Table 1: Clinically Defined Thresholds for Hypoglycemia

This table standardizes the classification of hypoglycemic events based on consensus guidelines [12].

| Classification | Glucose Threshold | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Hypoglycemia Alert (Level 1) | ≤70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L) | Indicates a value low enough to require intervention with fast-acting carbohydrates and/or medication adjustment. |

| Clinically Significant Hypoglycemia (Level 2) | <54 mg/dL (3.0 mmol/L) | Sufficiently low to indicate serious, clinically important hypoglycemia that is often accompanied by symptoms. |

| Severe Hypoglycemia (Level 3) | No specific glucose threshold | Defined by severe cognitive impairment requiring external assistance for recovery. |

Table 2: Representative Data on Counterregulatory Hormones in Type 1 Diabetes

This table presents sample data from a clinical study measuring hormone levels in type 1 diabetic patients, illustrating the relationship between these hormones and glucose control [13].

| Parameter | Measured Value (Mean ± SD) | Reference Range | Correlation with Fasting Blood Glucose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma Glucagon | 98 ± 41 pg/mL | 40 – 180 pg/mL | Positive (R=0.378, p=0.047) |

| Urinary GH SD Score | +1.01 ± 0.70 | 0 (Population Mean) | Not Significant |

| Serum Cortisol | 21.6 ± 5.5 µg/dL | 4.0 – 18.3 µg/dL | Not Significant |

| Urinary Cortisol | 238 ± 197 ng/gCr | Not Provided | Negative (R=-0.476, p=0.010) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing the Counterregulatory Hormone Response to Induced Hypoglycemia

Objective: To quantitatively measure the secretion kinetics of glucagon, epinephrine, cortisol, and growth hormone in response to a controlled hypoglycemic clamp.

Methodology:

- Subject Preparation: After an overnight fast, insert intravenous catheters for insulin/glucose infusion and frequent blood sampling.

- Hyperinsulinemic-Hypoglycemic Clamp: Initiate a fixed-rate insulin infusion to induce and maintain hypoglycemia. A variable-rate glucose infusion is used to clamp blood glucose at a target level (~50 mg/dL or 2.8 mmol/L) for a defined period (e.g., 90 minutes) [12].

- Blood Sampling: Collect blood samples at baseline and at regular intervals during the clamp.

- Samples for Glucose: Analyze immediately with a glucose analyzer.

- Samples for Hormones: Collect in pre-chilled tubes containing appropriate preservatives (e.g., EDTA for glucagon, EGTA/glutathione for catecholamines). Centrifuge immediately at 4°C and store plasma at -80°C until assay.

- Hormone Assays: Use commercially available, validated kits:

- Glucagon: Radioimmunoassay (RIA) or ELISA.

- Epinephrine/Norepinephrine: High-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection (HPLC-EC) or ELISA.

- Cortisol & Growth Hormone: Chemiluminescent immunoassay (CLIA) or ELISA.

Key Measurements:

- Glucose Infusion Rate (GIR): The amount of glucose required to maintain the hypoglycemic plateau is an inverse measure of the overall counterregulatory response.

- Hormone Peak Concentrations: The maximum plasma level reached for each hormone.

- Integrated Area Under the Curve (AUC): The total hormone output over time.

Protocol 2: Measuring Gluconeogenesis Flux in Primary Hepatocytes

Objective: To quantify the rate of gluconeogenesis in primary hepatocytes after stimulation with counterregulatory hormones.

Methodology:

- Hepatocyte Isolation and Culture: Isolate primary hepatocytes via collagenase perfusion from a model organism. Culture in a hormonally defined, serum-free medium.

- Treatment Groups:

- Control: Vehicle only.

- Glucagon Treatment: 10-100 nM glucagon.

- Cortisol Treatment: 100-500 nM cortisol.

- Combined Treatment: Glucagon + cortisol.

- Gluconeogenesis Assay:

- Incubate cells in glucose-production buffer containing a saturating concentration of a gluconeogenic precursor (e.g., 10 mM lactate + 1 mM pyruvate).

- After a set incubation period (e.g., 4-6 hours), collect the conditioned medium.

- Measure the accumulated glucose in the medium using a glucose assay kit (e.g., hexokinase/glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase coupled enzyme assay). Normalize the glucose concentration to total cellular protein content (e.g., via Bradford assay).

- Gene Expression Analysis (Optional): Extract RNA and perform RT-qPCR to measure the mRNA expression of key gluconeogenic enzymes, such as PEPCK and Glucose-6-Phosphatase, which are transcriptionally upregulated by these hormones [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Reagent | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Hyperinsulinemic-Hypoglycemic Clamp | The gold-standard in vivo method for inducing controlled hypoglycemia and directly quantifying the counterregulatory hormone response and glucose kinetics [12]. |

| Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) | Provides high-resolution, temporal data on glucose fluctuations, essential for detecting nocturnal hypoglycemia and differentiating the Somogyi effect from the dawn phenomenon [1] [2]. |

| Specific ELISA/RIA Kits | Validated immunoassays for the accurate and sensitive quantification of hormone levels (glucagon, cortisol, epinephrine, growth hormone) in plasma, serum, or urine samples [13]. |

| Primary Hepatocytes | A key in vitro model system for studying the direct effects of counterregulatory hormones on hepatic gluconeogenesis, glycogenolysis, and insulin signaling, free from systemic influences. |

| Stable Isotope Tracers (e.g., [U-¹³C]-lactate) | Used with Mass Spectrometry to precisely track the flux of substrates through the gluconeogenic pathway, allowing for direct measurement of gluconeogenesis rates in vivo or in vitro. |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Counterregulatory Hormone Response to Hypoglycemia

Hormonal Regulation of Key Gluconeogenic Enzymes

What is the defining characteristic of rebound hyperglycemia (Somogyi effect)?

Rebound hyperglycemia, or the Somogyi effect, is defined by a paradoxical rebound from nocturnal hypoglycemia to morning hyperglycemia [1] [3]. This phenomenon was first described by Dr. Michael Somogyi in the 1930s and posits that an episode of low blood glucose (hypoglycemia) during the night triggers a compensatory surge of counter-regulatory hormones (e.g., catecholamines, cortisol, growth hormone, glucagon) [1] [16]. This hormonal response stimulates hepatic glucose production via glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, leading to elevated blood glucose levels upon waking [1] [17]. In individuals with diabetes, the inability to secrete sufficient insulin prevents the correction of this elevated glucose, resulting in persistent hyperglycemia [3].

How does the dawn phenomenon differ from the Somogyi effect?

The dawn phenomenon is a distinct cause of morning hyperglycemia that is not preceded by hypoglycemia [18]. It is attributed to the body's normal circadian rhythm, involving a nocturnal surge of insulin-antagonistic hormones (including growth hormone, cortisol, and glucagon) in the early morning hours [19] [20]. This surge signals the liver to increase glucose output, providing energy to wake up [20]. In individuals without diabetes, a concomitant increase in insulin secretion suppresses hepatic glucose production. However, in diabetes, insufficient insulin production or insulin resistance leads to morning hyperglycemia [18] [20]. The dawn phenomenon is notably more prevalent than the Somogyi effect [1].

The table below summarizes the core differences:

| Feature | Somogyi Effect (Rebound Hyperglycemia) | Dawn Phenomenon |

|---|---|---|

| Core Mechanism | Counter-regulatory hormone response to nocturnal hypoglycemia [3] [16] | Circadian release of insulin-antagonistic hormones; not triggered by low glucose [18] [20] |

| Nocturnal Glucose Pattern | Hypoglycemia (low glucose) around 2-3 a.m., followed by hyperglycemia [17] | Normal or steadily rising glucose through the night and early morning [18] [17] |

| Primary Hormones Involved | Adrenaline, corticosteroids, growth hormone, glucagon [1] [3] | Cortisol, growth hormone, glucagon [18] [20] |

| Prevalence | Less common; subject to ongoing scientific debate [1] [3] | Very common; occurs in over 50% of individuals with both T1D and T2D [18] [20] |

The following diagram illustrates the distinct physiological pathways and resulting glucose profiles for the Somogyi effect versus the dawn phenomenon.

What is the scientific controversy surrounding the Somogyi effect?

The Somogyi effect is a subject of ongoing debate in the scientific community [1]. While it is a well-known concept among clinicians and patients, its existence as a common clinical entity is disputed by modern research utilizing continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) [1] [3].

- Evidence Against the Phenomenon: Some studies have found no correlation between nocturnal hypoglycemia and next-day hyperglycemia. For instance, one study concluded that nocturnal hypoglycemia did not cause daytime hyperglycemia and found no associated rise in counter-regulatory hormones [1]. Another CGM study on Type 1 diabetes patients found that morning hyperglycemia was not linked to nocturnal hypoglycemic events [1] [16].

- Evidence Supporting the Phenomenon: Conversely, other research has concluded that the Somogyi effect is the most common cause of fasting hyperglycemia in patients with Type 1 diabetes who have suboptimal glucose control [16].

- Current Consensus: The prevailing view in the field is shifting. Many experts now believe that early morning hyperglycemia is more frequently caused by the dawn phenomenon or simply by waning insulin levels from the previous evening's dose, rather than a rebound effect [1] [20]. Consequently, some recent clinical resources describe the Somogyi effect as a theory rather than an established fact [3].

What experimental protocols are used to distinguish these entities in a clinical research setting?

Accurate differentiation requires detailed monitoring of glucose levels throughout the night to establish the temporal sequence of events [3] [17].

Protocol 1: Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM)

The most effective method for diagnosis is the use of CGM, which provides a comprehensive profile of glucose fluctuations every few minutes without requiring the subject to wake up [18] [20].

- Equipment: A professional or personal CGM system.

- Procedure: Apply the CGM sensor as per manufacturer instructions. Collect data over a minimum of 2-3 consecutive nights to account for daily variability.

- Data Analysis: Plot the 24-hour glucose trace. Identify the nocturnal glucose nadir (lowest point) and the pre-breakfast glucose value.

- Somogyi Effect Profile: Glucose trace shows a distinct dip below the hypoglycemic threshold (typically <70 mg/dL) between 2:00 a.m. and 4:00 a.m., followed by a sharp rise to hyperglycemic levels by morning [16] [17].

- Dawn Phenomenon Profile: Glucose levels remain stable or gradually decline until approximately 3:00 a.m., after which a steady climb begins without any preceding hypoglycemic event [18].

Protocol 2: Intermittent Capillary Blood Glucose Testing

If CGM is unavailable, a structured intermittent testing protocol can be implemented.

- Equipment: Blood glucose meter, test strips, lancets, logbook.

- Procedure: The subject checks and records their blood glucose at the following times:

- At bedtime (e.g., 10:00 p.m.)

- Between 2:00 a.m. and 3:00 a.m.

- Immediately upon waking (e.g., 7:00 a.m.)

- Data Interpretation:

What are the key research reagents and materials for investigating these conditions?

Research into morning hyperglycemias relies on tools for precise glucose measurement, hormone assays, and controlled insulin delivery.

| Research Tool / Reagent | Primary Function in Investigation |

|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) | Captures high-resolution, interstitial glucose data to establish definitive nocturnal glucose patterns and differentiate between phenomena [18] [20]. |

| Immunoassays (ELISA/RIA) | Quantifies plasma levels of counter-regulatory hormones (e.g., Cortisol, Glucagon, Growth Hormone, Catecholamines) to confirm the underlying endocrine physiology [1]. |

| Long-Acting & Rapid-Acing Insulin Analogs | Used in controlled studies to manipulate nocturnal insulin levels and model waning insulin versus excess insulin conditions [20] [17]. |

| Standardized Meal / Enteral Formula | Provides a controlled carbohydrate and protein load for evening meals to eliminate dietary variability as a confounder in studies [20]. |

| Insulin Pump | Allows for precise, programmable delivery of basal insulin; critical for experiments testing time-specific insulin dosing to counteract the dawn phenomenon [18] [20]. |

How does the management approach differ based on the diagnosis?

The therapeutic strategy diverges completely based on the underlying cause, highlighting the critical importance of a correct diagnosis.

| Management Strategy | Somogyi Effect | Dawn Phenomenon |

|---|---|---|

| Insulin Adjustment | Reduce the dose or change the timing of insulin that is active overnight (e.g., decrease evening long-acting insulin or avoid rapid-acting insulin at supper) [16] [17]. | Increase overnight insulin action. This can be achieved by increasing basal insulin dose, switching to a longer-acting basal insulin, or using an insulin pump to administer an increased basal rate in the early morning hours [18] [20]. |

| Adjunct Therapies | Consuming a small bedtime snack containing complex carbohydrates and/or protein to prevent nocturnal hypoglycemia [16] [17]. | Evening exercise to improve overall insulin sensitivity; consuming a breakfast meal to counter hormone-mediated glucose release [18] [20]. |

| Key Caution | Increasing insulin dose in response to morning hyperglycemia, without investigation, will worsen the nocturnal hypoglycemia and perpetuate the cycle [17]. | Increasing evening insulin without confirming the diagnosis can inadvertently induce nocturnal hypoglycemia, potentially creating a Somogyi-like effect [20]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the Somogyi effect, and what was its original proposed mechanism?

The Somogyi effect, also known as "posthypoglycemic hyperglycemia" or "rebound hyperglycemia," is a theory proposed in the 1930s by Dr. Michael Somogyi. It describes a paradoxical reaction where the body responds to an episode of hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) by producing hyperglycemia (high blood sugar). The mechanism he proposed suggests that when blood glucose drops too low, particularly overnight, it triggers the release of counterregulatory hormones (such as adrenaline, cortisol, growth hormone, and glucagon). This hormonal surge activates gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis, leading to a rebound high blood glucose level, most notably in the early morning [21] [1] [16].

Q2: How does Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) evidence challenge the traditional Somogyi theory?

Modern CGM evidence challenges the Somogyi theory on two main fronts: frequency and causality.

- Lack of Frequent Rebound: CGM studies have shown that nocturnal hypoglycemia is more frequently followed by normal or low fasting glucose levels, not hyperglycemia. One key study of 89 patients with Type 1 Diabetes found that fasting capillary glucose was more likely to be lower following nocturnal hypoglycemia, with only two instances of glucose exceeding 180 mg/dL [2] [1].

- Questioned Hormonal Response: Research has indicated that even when rebound hyperglycemia occurs, it is not consistently associated with elevated levels of counterregulatory hormones like glucagon, epinephrine, growth hormone, or cortisol, which is a cornerstone of the original Somogyi theory [1] [16].

The table below summarizes key CGM study findings that dispute the theory:

| Study Focus | Key Findings from CGM Evidence | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency of Rebound Hyperglycemia [2] | Following nocturnal hypoglycemia, fasting glucose was more often low, with only 2.2% of cases (2/89) showing glucose >180 mg/dL. | The Somogyi effect is a rare occurrence, not a common cause of morning hyperglycemia. |

| Hormonal Response [1] | Daytime hyperglycemia following nocturnal hypoglycemia showed no correlation with increased levels of glucagon, epinephrine, growth hormone, or cortisol. | The postulated counterregulatory hormone surge driving the rebound is not reliably observed. |

| Causality in Morning Hyperglycemia [1] | Patients with early morning hyperglycemia were observed to have high blood glucose measurements at night rather than low ones. | Morning hyperglycemia is more likely caused by other factors, such as the dawn phenomenon or waning insulin. |

Q3: What is the difference between the Somogyi effect and the dawn phenomenon?

It is crucial for researchers to distinguish between these two concepts, as their management strategies differ. The table below outlines the key differences:

| Feature | Somogyi Effect (Theoretical) | Dawn Phenomenon (Common) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Cause | Rebound effect from nocturnal hypoglycemia. | Natural early morning release of counterregulatory hormones (e.g., growth hormone, cortisol). |

| Nocturnal Glucose | Low (hypoglycemic) around 2:00 a.m. - 3:00 a.m. [16] [3] | Normal or steadily rising. |

| Morning Glucose | High (hyperglycemic). | High (hyperglycemic). |

| Prevalence | Considered rare and controversial [3] [2]. | A common occurrence in both diabetic and non-diabetic individuals [1]. |

| Proposed Research Solution | Reduce evening insulin dose to prevent nocturnal lows. | Increase or adjust timing of evening insulin to counteract morning hormone surge. |

Q4: What are the essential components of an experimental protocol to investigate rebound hyperglycemia?

A robust protocol to study this phenomenon requires frequent glucose measurement and careful hormone analysis.

- Participants: Recruit individuals with Type 1 Diabetes on insulin therapy.

- Glucose Monitoring: Utilize Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) systems for seamless, high-frequency (e.g., every 5 minutes) glucose tracking throughout the night and day [22] [2]. This is superior to intermittent finger-stick checks.

- Critical Time Points: If CGM is unavailable, mandate manual blood glucose measurements at key intervals: two hours after the evening meal, at bedtime, at 3:00 a.m., and upon waking [3].

- Hormonal Assays: Collect blood samples during suspected hypoglycemic and subsequent hyperglycemic events to measure levels of counterregulatory hormones (glucagon, cortisol, epinephrine, growth hormone).

- Data Correlation: Analyze the data for temporal relationships between nocturnal hypoglycemia, hormone surges, and morning hyperglycemia.

Q5: What are common technical challenges when using CGM in a clinical study, and how can they be troubleshooted?

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Loss Alarm | Sensor and reader are too far apart (beyond 6 meters/20 feet). | Ensure devices are within range. Try scanning the sensor manually. If persistent, replace the sensor [23]. |

| Sensor Error / Glucose Reading Unavailable | Inability to communicate with sensor; sensor too hot or too cold. | Move to a location with appropriate temperature (10°C - 45°C) and scan again after 10 minutes [23]. |

| Skin Irritation | Sensitivity to adhesive or friction from clothing. | Ensure application site is clean and dry. Consult a healthcare professional to identify hypoallergenic solutions [23]. |

| Inconsistent Data | Sensor may not be properly calibrated or may be failing. | Follow manufacturer calibration guidelines. If errors persist, replace the sensor and document the event [23]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Differentiating Causes of Morning Hyperglycemia

Objective: To determine whether a subject's morning hyperglycemia is attributable to the Somogyi effect, the dawn phenomenon, or chronic insulin underdosing.

Materials:

- Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) system or blood glucose meter with test strips.

- Data log sheet for food, insulin, and activity.

Methodology:

- Instruct the subject to maintain their usual insulin regimen, diet, and exercise for the study duration.

- For three consecutive nights, collect blood glucose readings at the following times:

- Between 10:00 p.m. and 11:00 p.m. (before bed)

- Between 2:00 a.m. and 3:00 a.m. (nocturnal)

- Upon waking between 6:00 a.m. and 8:00 a.m. (fasting)

- If using CGM, ensure it is active and recording data throughout this period.

- Correlate the nocturnal glucose reading with the morning fasting reading.

Interpretation of Results:

- Somogyi Effect Suspected: Nocturnal glucose is low (<70 mg/dL) followed by high morning fasting glucose [16].

- Dawn Phenomenon Suspected: Nocturnal glucose is normal or stable followed by a rise to high morning fasting glucose [2].

- Chronic Insulin Underdosing: Glucose levels are high at all measurement points (bedtime, nocturnal, and morning), indicating persistent insulin deficiency [1].

Protocol 2: Investigating the Counterregulatory Hormone Response

Objective: To quantify the relationship between nocturnal hypoglycemia and the subsequent release of counterregulatory hormones.

Materials:

- CGM system.

- Venous blood collection kits (e.g., vacutainers, butterflies).

- Centrifuge and freezer for serum/plasma separation and storage.

- ELISA or RIA kits for glucagon, cortisol, epinephrine, and growth hormone.

Methodology:

- Admit study participants to a clinical research unit for overnight monitoring.

- Set CGM alarms to alert staff at a predefined hypoglycemic threshold (e.g., 63 mg/dL).

- Upon CGM alarm confirming hypoglycemia, immediately collect a baseline blood sample for hormone analysis.

- Treat the hypoglycemic event according to a standardized protocol.

- Continue to collect blood samples at 30-minute intervals for the next 2-3 hours to track hormone levels and glucose trends.

- Compare hormone profiles from nights with hypoglycemia to control nights without hypoglycemia.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

The table below details key materials and their functions for conducting research in this field.

| Item | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitor | Provides high-frequency, interstitial glucose measurements with minimal participant disturbance; essential for detecting asymptomatic nocturnal hypoglycemia and tracking glucose trends [22]. |

| Insulin Pumps | Allows for precise and programmable delivery of insulin; useful for standardizing basal rates or testing different insulin delivery patterns to provoke or prevent nocturnal hypoglycemia. |

| ELISA Kits | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits for the quantitative measurement of counterregulatory hormones (glucagon, cortisol, growth hormone) in serum/plasma samples. |

| Blood Collection Tubes | Including tubes with appropriate anticoagulants (e.g., EDTA for plasma) and preservatives for stable hormone analysis. |

| Glycated Hemoglobin (HbA1c) Test | Measures average blood glucose over the preceding 2-3 months; a low or in-range HbA1c in the context of morning hyperglycemia can support a theory of rebound from overtreatment [2]. |

Signaling Pathways and Conceptual Workflows

Somogyi Theory vs CGM Evidence

Morning Hyperglycemia Investigation

The Somogyi effect, also known as posthypoglycemic hyperglycemia or rebound hyperglycemia, is a phenomenon historically proposed to explain high morning blood glucose levels following an untreated nocturnal hypoglycemic episode. First described in the 1930s by Dr. Michael Somogyi, it theorizes that the body reacts to nighttime hypoglycemia by activating counterregulatory hormones (such as adrenaline, corticosteroids, growth hormone, and glucagon), leading to increased glucose production and resultant morning hyperglycemia [1] [3]. Within the broader context of managing hypoglycemia and rebound hyperglycemia, understanding the epidemiology and clinical relevance of the Somogyi effect is crucial for researchers and clinicians aiming to optimize glycemic control and interpret complex glucose patterns.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: What is the fundamental pathophysiological pathway of the Somogyi effect?

A1: The proposed sequence involves a hypoglycemic trigger, leading to a counterregulatory hormone response, which subsequently causes rebound hyperglycemia. The diagram below illustrates this theoretical pathway.

Q2: How can I differentiate the Somogyi effect from the Dawn Phenomenon in a research or clinical setting?

A2: The key differentiator is the presence or absence of a preceding hypoglycemic event. The table below outlines the core differences.

| Feature | Somogyi Effect | Dawn Phenomenon |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Cause | Rebound from nocturnal hypoglycemia [1] [3] | Natural early-morning hormone surge (e.g., cortisol, growth hormone) [1] [20] |

| Nocturnal Glucose | Documented hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL) [24] | Stable or steadily rising glucose without hypoglycemia [1] |

| Prevalence | Less common; recent studies question its prevalence [1] | Very common; affects up to half of people with diabetes [20] |

| Research Diagnosis | Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) showing hypoglycemia followed by hyperglycemia before 6:00 am [24] | CGM showing hyperglycemia without a preceding hypoglycemic event [1] |

Q3: What does current epidemiological data reveal about the prevalence of the Somogyi effect?

A3: Recent data from a 2025 study using Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) provides the most current prevalence figures. The table below summarizes key epidemiological metrics.

| Metric | Finding | Source / Study Details |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Prevalence in T1DM | 32.8% of patients experienced at least one episode of Post-Hypoglycemic Nocturnal Hyperglycemia (PHNH) over 14 days [24] | N = 755 T1DM patients using FreeStyle Libre 2 CGM [24] |

| Associated Glycemic Control | Patients with PHNH had longer Time Above Range, shorter Time in Range, and higher glucose variability than those with nocturnal hypoglycemia alone [24] | Cross-sectional study [24] |

| Controversy & Evidence | Some clinical studies and reviews dispute the theory, finding no causal link between nocturnal hypoglycemia and subsequent daytime hyperglycemia [1] | Earlier studies observed high nighttime glucose rather than low in patients with morning hyperglycemia [1] |

Q4: What are the primary risk factors associated with Post-Hypoglycemic Nocturnal Hyperglycemia (PHNH)?

A4: A 2025 study identified specific patient factors linked to a higher likelihood of experiencing PHNH. The table below lists these associated factors.

| Associated Factor | Description |

|---|---|

| Younger Age | Patients with PHNH were significantly younger [24] |

| Higher Insulin Doses | Use of higher total daily doses of insulin [24] |

| Insulin Therapy (T2DM) | Insulin use is a primary risk factor for hypoglycemia, a prerequisite for PHNH [25] [26] |

| Longer Diabetes Duration | Duration greater than 13.7 years is a key predictor of hypoglycemia [26] |

| Renal Impairment | Reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR < 60.2 mL/min/1.73 m²) [26] |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating the Somogyi Effect

Protocol 1: Establishing Phenomena Prevalence with CGM

This protocol outlines the methodology used in a recent study to determine the frequency of PHNH [24].

- 1. Objective: To determine the frequency and associated factors of post-hypoglycemic nocturnal hyperglycemia (PHNH) in patients with Type 1 Diabetes.

- 2. Study Design: Cross-sectional observation of CGM data.

- 3. Population:

- Inclusion: Patients with T1DM (defined by positivity for pancreatic islet autoantibodies and insulin requirement), age ≥18 years, sensor usage ≥70%.

- Exclusion: Patients with stage 1 T1DM, those under 18 years, and pregnant women.

- 4. Data Collection & Tools:

- Primary Tool: FreeStyle Libre 2 CGM system [24].

- Period: Analyze a consecutive 14-day period of CGM data.

- Platform: Use cloud-based platform (e.g., LibreView) to collect glucose data.

- 5. Operational Definitions:

- Nocturnal Hypoglycemia: A glucose value <70 mg/dL recorded between 0:00 am and 6:00 am.

- PHNH Episode: Nocturnal hypoglycemia followed by a glucose value >180 mg/dL before 6:00 am.

- 6. Data Analysis:

- Categorize patients into three groups: (1) No nocturnal hypoglycemia, (2) Nocturnal hypoglycemia without hyperglycemia, (3) ≥1 PHNH episode.

- Compare glycemic metrics (Time in Range, Time Above Range, glucose variability) and patient characteristics (age, insulin dose) between groups using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., chi-square, Mann-Whitney U test) [24].

Protocol 2: Differentiating Dawn Phenomenon vs. Somogyi Effect in Individuals

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for diagnosing the cause of morning hyperglycemia in a clinical research setting [3] [20].

- 1. Objective: To identify the etiology (Dawn Phenomenon vs. Somogyi Effect) of unexplained morning hyperglycemia in an individual subject.

- 2. Materials:

- Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) OR blood glucometer and test strips.

- Blood glucose and symptom log.

- 3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Instruct the subject to maintain their usual evening routine regarding diet, medication, and exercise.

- Step 2: Schedule blood glucose measurements (if not using CGM) at the following times:

- Two hours after the evening meal.

- At bedtime (e.g., 10:00-11:00 PM).

- Between 2:00 AM and 4:00 AM.

- Immediately upon waking.

- Step 3: If using CGM, ensure the device is active and functioning to automatically capture this data [24] [20].

- Step 4: Repeat this process for 3-7 nights to establish a pattern.

- 4. Data Interpretation:

- Consistent Low at 2:00-4:00 AM → High on Waking: Pattern consistent with the Somogyi effect.

- Normal at 2:00-4:00 AM → Steady Rise until Waking: Pattern consistent with the dawn phenomenon.

- High at All Measurement Points: Indicates general insulin insufficiency or dietary factors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below details key tools and materials for conducting research on the Somogyi effect and related glycemic phenomena.

| Tool / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) | Core tool for capturing interstitial glucose levels continuously, enabling detection of asymptomatic nocturnal hypoglycemia and precise tracking of glycemic rebounds [24] [20]. |

| Cloud-Based Data Platforms (e.g., LibreView) | Facilitates the aggregation and analysis of large-scale CGM data from study participants, allowing for remote monitoring and data export [24]. |

| Standardized Hypoglycemia Definition | Critical for consistent phenotyping. Level 1: <70 mg/dL; Level 2: <54 mg/dL; Level 3: severe event requiring assistance [25] [26]. |

| Immunoassay Kits | For measuring counterregulatory hormones (glucagon, cortisol, growth hormone, epinephrine) to objectively validate the physiological response following hypoglycemia [1]. |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Used to analyze complex, non-linear relationships between multiple risk factors (e.g., insulin dose, eGFR, age) and the incidence of hypoglycemia/PHNH in large datasets [26]. |

Advanced Methodologies for Investigating and Quantifying Rebound Hyperglycemia

The Role of Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) in Phenomenon Detection

Scientific Context: CGM and the Somogyi Effect

What is the Somogyi effect and why is it a topic of research?

The Somogyi effect, also known as rebound hyperglycemia, is a theory proposing that nocturnal hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) triggers a counter-regulatory hormonal response (e.g., adrenaline, cortisol, growth hormone, glucagon), leading to hyperglycemia (high blood sugar) by morning [1] [3]. This phenomenon was named after Dr. Michael Somogyi, who described it in the 1930s [1]. For researchers, the effect highlights a complex physiological interplay between hypoglycemia and subsequent hyperglycemia, which is crucial for understanding glycemic variability and optimizing diabetes therapeutics [1] [3].

What is the current scientific consensus on the Somogyi effect?

Recent evidence from studies utilizing Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) has disputed the validity of the Somogyi effect [1] [3]. Modern research indicates that morning hyperglycemia is more frequently caused by the dawn phenomenon (a natural early-morning release of hormones that increase blood sugar) or simple insulin waning overnight [1] [27]. A key study concluded that nocturnal hypoglycemia did not cause daytime hyperglycemia and found no correlation between daytime glucose levels and counter-regulatory hormones [1]. This ongoing debate underscores the importance of precise measurement tools like CGM in clinical and research settings.

CGM Troubleshooting Guide for Research Settings

What are the first steps if a research CGM sensor fails?

If a sensor fails or an applicator malfunctions during a study:

- Do not reapply or reuse the sensor [28].

- Document the incident and save the sensor and its packaging for the manufacturer's analysis [28].

- Contact the manufacturer immediately for a replacement. Provide the sensor's serial number and details of the failure [28] [29].

Table 1: Manufacturer Contact Information for Research Device Support

| Manufacturer | CGM Models | Support Contact |

|---|---|---|

| Abbott | FreeStyle Libre | 1800 801 478 [29] |

| Dexcom | Dexcom G-series | 1300 851 056 [29] |

| Medtronic | Guardian Connect | 1800 777 808 [29] |

How can we prevent sensors from detaching during long-term studies?

Proper adhesion is critical for data integrity. To ensure sensors remain secure:

- Skin Preparation: Clean the application site with an alcohol wipe and allow it to dry completely. Avoid using lotions or oils beforehand [28].

- Adhesive Enhancers: Use approved liquid adhesives or adhesive patches over the sensor for extra security, especially in studies involving exercise or water exposure [28] [29].

- Site Selection: Rotate application sites to avoid skin irritation, and choose areas less likely to be bumped or rubbed [28] [29].

How should we address signal loss between the CGM and receiver?

Signal loss can create gaps in research data. To troubleshoot:

- Proximity: Ensure the receiver (e.g., smartphone) is within 5-6 meters of the sensor [29].

- Bluetooth: Toggle the Bluetooth function on the receiver off and back on [28].

- Interference: Check for and mitigate potential electromagnetic interference from other lab equipment [29].

- Pressure: Avoid applying direct pressure to the sensor, as this can disrupt signals [28].

What steps ensure the accuracy of CGM data in a clinical trial?

To maintain data accuracy and reliability:

- Verify with Blood Glucose Meter (BGM): If CGM readings seem erratic or improbable, compare them with a fingerstick BGM measurement, especially during rapid glucose fluctuations, as CGM readings can lag behind blood glucose by 5-10 minutes [30] [29] [27].

- Check Sensor Warm-up: Ensure the sensor has completed its initial warm-up period (typically up to 2 hours) before recording data [29].

- Monitor Sensor Lifespan: Replace sensors at or before the end of their recommended usage period (usually 7-14 days) [29].

- Environmental Controls: Protect sensors from extreme temperatures, humidity, and direct sunlight [29].

Interpreting CGM Data for Phenomenon Detection

What are the key CGM metrics for analyzing glycemic patterns?

CGM provides standardized metrics that are essential for quantifying glucose control in study participants. A minimum of 14 days of data with at least 70% sensor wear is recommended for a reliable assessment [30] [27].

Table 2: Core CGM Metrics for Clinical Research

| Metric | Definition | Research Significance / Target |

|---|---|---|

| Time in Range (TIR) | % of readings/day within 70-180 mg/dL [30] [27] | Primary outcome for therapy efficacy. Goal >70% [27]. |

| Time Below Range (TBR) | % of readings/day <70 mg/dL (Level 1) and <54 mg/dL (Level 2) [30] | Key for Somogyi hypothesis. Measures hypoglycemia exposure. Goal <4% [27]. |

| Time Above Range (TAR) | % of readings/day >180 mg/dL (Level 1) and >250 mg/dL (Level 2) [30] | Measures hyperglycemia exposure. Goal <25% [27]. |

| Glucose Management Indicator (GMI) | Estimated A1C derived from mean CGM glucose [30] | Predicts lab-measured A1C for long-term control assessment. |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | (Standard Deviation / Mean Glucose) * 100 [30] | Measures glycemic variability. A CV <36% indicates stable glucose [30]. |

How do I use trend arrows to detect rapid glucose changes?

CGM trend arrows provide real-time direction and velocity of glucose change, which is critical for identifying rapid shifts that might be associated with rebound phenomena [31].

Table 3: Interpretation of CGM Trend Arrows

| Trend Arrow | Interpretation (Change per 30 min) | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Rising Rapidly | >90 mg/dL / >5.0 mmol/L [31] | Potential indicator of counter-regulatory hormone surge. |

| Rising | 60-90 mg/dL / 3.3-5.0 mmol/L [31] | Monitor for sustained upward trend. |

| Rising Slowly | 30-60 mg/dL / 1.7-3.3 mmol/L [31] | Common after meals; baseline rate. |

| Stable | Changing <30 mg/dL / <1.7 mmol/L [31] | Steady state; ideal baseline condition. |

| Falling Slowly | -30 to -60 mg/dL / -1.7 to -3.3 mmol/L [31] | Monitor for progression to hypoglycemia. |

| Falling | -60 to -90 mg/dL / -3.3 to -5.0 mmol/L [31] | May require intervention in a study protocol. |

| Falling Rapidly | >-90 mg/dL / >-5.0 mmol/L [31] | Critical for Somogyi trigger; indicates significant hypoglycemic event. |

What is the standard method for visualizing CGM data patterns?

The Ambulatory Glucose Profile (AGP) is the consensus standard for visualizing retrospective CGM data [30] [27]. This single-page report collapses 14 days of data into a single 24-hour graph, providing a modal day view that highlights patterns of hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, and variability [27].

Experimental Protocols for Somogyi Effect Research

What is a standard protocol for investigating overnight glycemic patterns?

Objective: To detect and correlate nocturnal hypoglycemic events with morning hyperglycemia. Methodology:

- Participant Selection: Recruit insulin-dependent diabetic subjects.

- CGM Deployment: Apply a research-grade CGM device. Ensure proper calibration if required.

- Data Collection Period: Collect continuous glucose data for a minimum of 14 nights [30] [27].

- Supplementary Measurements: For validation, schedule periodic fingerstick blood glucose measurements at: Two hours after evening meal, Before bedtime, 2:00 AM - 4:00 AM, Upon waking [3].

- Data Points: Record diet, evening exercise, and insulin dosing.

Analysis:

- Use the AGP report to identify recurring patterns.

- Quantify the frequency of nocturnal hypoglycemia (glucose <70 mg/dL and <54 mg/dL) and the corresponding morning glucose values [30].

- Statistically analyze the correlation between nocturnal hypoglycemia and morning hyperglycemia.

How can we differentiate the Somogyi effect from the dawn phenomenon?

This protocol uses CGM data to distinguish between two causes of morning hyperglycemia.

Table 4: Differential Diagnosis Using CGM Data

| Characteristic | Somogyi Effect | Dawn Phenomenon |

|---|---|---|

| Overnight Pattern | Documented hypoglycemia (e.g., <70 mg/dL) between 2:00 AM - 4:00 AM [3]. | Stable glucose followed by a rise in the early morning (e.g., ~3:00 AM - 8:00 AM) [1]. |

| Morning Glucose | Hyperglycemia upon waking [3]. | Hyperglycemia upon waking [1]. |

| Primary Cause | Rebound from hypoglycemia due to counter-regulatory hormones [1]. | Natural circadian release of growth hormone, cortisol, etc. [1]. |

| Research Implication | May indicate excessive insulin therapy overnight. | May indicate insufficient insulin therapy overnight [1]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Materials and Reagents for CGM-Based Investigations

| Item | Function in Research | Example Brands/Models |

|---|---|---|

| Professional CGM Systems | Clinic-owned devices for intermittent, standardized assessment of glucose patterns in study cohorts [27]. | Abbott FreeStyle Libre Pro, Dexcom G6 Pro, Medtronic iPro2 [27]. |

| Real-Time Personal CGM | For longitudinal studies requiring continuous patient feedback and real-time data collection [27]. | Dexcom G7, Abbott FreeStyle Libre 3, Medtronic Guardian Connect [28] [27]. |

| CGM Adhesive Patches | Secures the sensor for the entire wear duration, critical for data integrity in studies involving sweat or water [28]. | Various overpatches from Skin Grip, Lexcam, Fixic [28]. |

| Liquid Skin Adhesive | Enhances sensor adhesion and prevents premature detachment; essential for rigorous trials [28] [29]. | Products like Skin-Tac [28]. |

| Adhesive Remover | Safely removes sensors without damaging the skin, important for participant compliance in long-term studies [28] [29]. | Wipes containing isopropyl alcohol or specialized solutions [28]. |

| Standardized AGP Report Software | Generates consensus-based reports for uniform data analysis and presentation across research sites [30] [27]. | Software from CGM manufacturers (LibreView, Clarity, CareLink) [27]. |

| Blood Glucose Meter (BGM) | Provides fingerstick reference values to validate CGM accuracy during the study period [29]. | Contour Next One, Accu-Chek Guide, OneTouch Verio [29]. |

FAQs on Rebound Hyperglycemia (Somogyi Effect)

What is the operational definition of a Rebound Hyperglycemia (RH) event for clinical research?

An RH event is quantitatively defined as any series of one or more sensor glucose values (SGVs) >180 mg/dL that starts within two hours of an antecedent SGV <70 mg/dL [32]. Studies may also analyze a severe subset of these events, defined as hyperglycemia following an SGV nadir of <55 mg/dL [32].

What are the standard metrics for quantifying Rebound Hyperglycemia in study populations?

Research quantifies RH using three primary metrics, which allow for objective comparison between study phases or treatment groups. The table below summarizes typical findings from a real-world analysis [32].

| Metric | Definition | Example Baseline Value (Mean) | Example Reduction with Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Number of RH events per week per patient [32]. | 2.39 events/week (after hypoglycemia <70 mg/dL) [32] | 14% with rtCGM use [32]. |

| Duration | Consecutive minutes of SGVs >180 mg/dL following hypoglycemia [32]. | 215 minutes (after hypoglycemia <70 mg/dL) [32] | 12% with rtCGM use [32]. |

| Severity | Area under the curve (AUC) for glucose concentration >180 mg/dL (mg/dL × min) [32]. | 15,476 mg/dL × min (after hypoglycemia <70 mg/dL) [32] | 23% with rtCGM use [32]. |

How does the prevalence of post-hypoglycemic nocturnal hyperglycemia (PHNH) characterize a study cohort?

A 2024 study of 755 users of the FreeStyle Libre 2 CGM system found that 32.8% (248 patients) experienced at least one episode of PHNH (a specific form of RH) over a 14-day observation period [24]. This metric helps define the scale of the problem within a population. The study further characterized these patients as having poorer overall glycemic control, including longer time above range and higher glucose variability, compared to those with nocturnal hypoglycemia not followed by hyperglycemia [24].

What is the pathophysiological sequence of the Somogyi effect? The following diagram illustrates the theorized sequence of events leading to rebound hyperglycemia, driven by the body's counter-regulatory response.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Assessing Impact of Real-Time CGM (rtCGM) on RH

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of real-time continuous glucose monitoring (rtCGM) in mitigating the frequency, duration, and severity of rebound hyperglycemia [32].

Population: Hypoglycemia-unaware individuals with type 1 diabetes (e.g., n=75 as in the HypoDE trial) [32].

- Inclusion Criteria: Type 1 diabetes, impaired awareness of hypoglycemia or recent history of severe hypoglycemia, use of multiple daily insulin injections [32].

- Intervention Group: Uses an rtCGM system (e.g., Dexcom G5/G6) with alerts enabled [32].

Study Design:

- Baseline Phase (4 weeks): Participants wear a blinded rtCGM. Data is collected but not visible to them [32].

- Intervention Phase (4 weeks): Participants wear an unblinded rtCGM and use the system's predictive alerts [32].

- Data Analysis: RH events are identified and quantified from CGM data. Within-patient comparisons of RH metrics (frequency, duration, severity) between the baseline and intervention phases are performed using paired t-tests [32].

Protocol: Analyzing Nocturnal Glycemic Profiles for PHNH

Objective: To determine the prevalence and associated factors of post-hypoglycemic nocturnal hyperglycemia (PHNH) in a type 1 diabetes cohort using CGM [24].

Population: Large cohort of CGM users with type 1 diabetes (e.g., n=755 with FreeStyle Libre 2) [24].

- Inclusion Criteria: Diagnosis of T1DM, sensor usage ≥70% over a 14-day period [24].

Methodology:

- Data Extraction: Nocturnal (00:00 - 06:00) glycemic profiles are analyzed over 14 days via a cloud-based platform (e.g., LibreView) [24].

- Event Classification: Patients are categorized into:

- No nocturnal hypoglycemia

- Nocturnal hypoglycemia only (SGVs <70 mg/dL not followed by hyperglycemia before 6:00 am)

- PHNH Group (≥1 episode of nocturnal hypoglycemia followed by SGV >180 mg/dL before 6:00 am) [24].

- Statistical Analysis: Compare patient characteristics, insulin therapy, and overall glycemic control (Time in Range, glucose variability) between groups using chi-square, Mann-Whitney tests, and multivariate logistic regression [24].

The workflow for this analysis is standardized as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Tool | Function in RH Research |

|---|---|

| Real-Time CGM (e.g., Dexcom G6) | Provides continuous interstitial glucose measurements. The "Urgent Low Soon" predictive alert warns of impending hypoglycemia, enabling study of its preventive effect on RH [32]. |

| Intermittently Scanned CGM (e.g., FreeStyle Libre 2) | Enables large-scale, real-world observational studies of nocturnal glycemic patterns and PHNH prevalence through cloud-based data aggregation [24]. |

| Blinded CGM (e.g., Dexcom G4 with Software 505) | Serves as a critical control tool during baseline study phases to collect data without influencing patient behavior, establishing a within-subject comparative baseline [32]. |

| Cloud Data Platforms (e.g., LibreView) | Facilitates the collection, aggregation, and analysis of anonymized, large-scale CGM data from real-world users for epidemiological studies on RH [24]. |

| Counter-Regulatory Hormone Assays | Used in mechanistic studies to measure plasma levels of glucagon, epinephrine, cortisol, and growth hormone to validate the physiological response to induced hypoglycemia [1] [2]. |

Predictive Algorithms for Hypoglycemia and Mitigation of Subsequent Hyperglycemia

FAQs: Algorithm Development and Clinical Application

Q1: What types of data are most critical for building predictive models for hypoglycemia?

The most effective predictive models integrate multiple data types. Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) data is foundational, providing real-time, high-frequency glucose readings [33]. From this signal, short-term (e.g., rate of change in the past hour), medium-term (e.g., standard deviation over 2-4 hours), and long-term features (e.g., percentage of time in hypo-/hyperglycemia) can be extracted [33]. Electronic Health Record (EHR) data adds crucial context, including laboratory results (e.g., HbA1c, serum creatinine), demographic information, and medication use [34] [35]. For enhanced accuracy, contextual data on insulin delivery and carbohydrate intake can be incorporated, though its impact is more pronounced for longer prediction horizons [33].

Q2: What is the typical performance of current machine learning models in predicting hypoglycemia?

Model performance varies based on the prediction horizon and data sources. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Hypoglycemia Prediction Models

| Study Context | Prediction Horizon | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | Key Algorithm(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth with T1D (CGM data) [33] | 30-minute | >91% | >90% | - | Machine Learning (Feature-based) |

| Youth with T1D (CGM data) [33] | 60-minute | >91% | >90% | - | Machine Learning (Feature-based) |

| Hospitalized Patients (EHR data) [34] | 7-hour (median) | 59.0% | 98.9% | - | Gradient Boosted Trees |

| Hospitalized T2DM Patients (EHR data) [35] | - | - | - | 0.960 | Random Forest |

Q3: How can researchers validate the occurrence of the Somogyi effect in a clinical study?

Validation requires frequent blood glucose monitoring to detect the characteristic pattern of nocturnal hypoglycemia followed by morning hyperglycemia [3] [4] [16]. The recommended protocol is to measure blood glucose at the following times:

- Before bed [3]

- Between 2:00 a.m. and 3:00 a.m. (or during the peak action time of evening insulin) [3] [4] [16]

- Upon waking [3]

A diagnosis of the Somogyi effect is suggested by low blood sugar (<4.0 mmol/L or 70 mg/dL) at the nighttime check and high blood sugar upon waking [4] [16]. Using Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) is the most robust method, as it provides a continuous record of glucose fluctuations throughout the night [3] [33].

Q4: What are the primary challenges in differentiating the Somogyi effect from the dawn phenomenon?

The core challenge is that both conditions present with the same clinical finding: hyperglycemia upon waking [3] [1]. However, their underlying mechanisms are fundamentally different. The Somogyi effect is a rebound phenomenon triggered by nocturnal hypoglycemia, which stimulates a counter-regulatory hormone response [3] [1]. In contrast, the dawn phenomenon is a natural rise in blood sugar in the early morning due to circadian hormone secretion (e.g., growth hormone, cortisol) and is not preceded by hypoglycemia [3] [1] [16]. The only way to distinguish them is through nighttime glucose measurement [16].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Developing a Multiclass Blood Glucose Decompensation Prediction Model from EHR Data

This protocol is based on a large-scale retrospective study using EHR data to predict hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia [34].

1. Study Design and Cohort Selection:

- Design: Conduct a retrospective cohort study.

- Data Source: Use anonymized hospital admission data from a defined period.

- Inclusion Criteria: Include admissions for adult inpatients (≥18 years) with at least one laboratory BG measurement and one of the following:

- A diagnosis of diabetes or related syndrome (using ICD codes).

- Administration of an antidiabetic drug (ATC code A10).

- An extreme BG measurement (<4.0 or ≥11.1 mmol/L) regardless of diagnosis [34].

2. Data Preprocessing and Cleaning:

- Deduplication: Remove duplicate records based on unique case identifiers [34].

- Variable Cleaning:

3. Outcome Definition:

- Define Blood Glucose (BG) decompensation events using the following categories [34]:

- Category 0 (Nondecompensated): BG ≥3.9 to ≤10 mmol/L

- Category 1 (Hypoglycemia): BG <3.9 mmol/L

- Category 2 (Mild Hyperglycemia): BG >10 to ≤13.9 mmol/L

- Category 3 (Moderate Hyperglycemia): BG >13.9 to ≤16.7 mmol/L

- Category 4 (Severe Hyperglycemia): BG >16.7 mmol/L

4. Feature Engineering:

- For each patient admission, use data from a defined "look-back window" prior to a decompensation event.

- For each laboratory analyte in the EHR, calculate derived statistics to capture patient status, including [34]:

- Central Tendency & Spread: Mean, Standard Deviation (SD), Interquartile Range (IQR)

- Range and Extremes: Total range, Minimum value, Maximum value

- Temporal Trends: Recent trend, Most recent value

- Frequency: Analysis count

5. Model Training and Evaluation:

- Algorithm: Employ a second-level ensemble of gradient-boosted binary trees [34].

- Validation: Use appropriate cross-validation techniques suitable for time-series patient data.

- Key Metrics: Evaluate model performance using Specificity and Sensitivity for each decompensation category. Calculate the median prediction horizon (the time between the prediction and the actual event) [34].

Diagram 1: EHR Model Development Workflow

Protocol for a Feature-Based Machine Learning Model Using CGM Data

This protocol details the process for developing a model to predict short-term hypoglycemia risk from CGM data [33].

1. Data Collection:

- Source: Collect CGM data from patients under normal living conditions over an extended period (e.g., 90 days).

- Contextual Data: If available, collect corresponding data on insulin delivery (e.g., from insulin pumps) and carbohydrate intake [33].

2. Feature Extraction:

- Extract a comprehensive set of features from the CGM time-series signal. The following table catalogs a recommended set of features [33].

Table 2: Feature Categories for CGM-Based Prediction Models

| Category | Description | Example Features |

|---|---|---|

| Short-Term | Captures patterns within the last hour. | Current glucose; Difference in glucose from 10, 20, 30 mins ago; Slope over 1 hour [33]. |

| Medium-Term | Captures patterns from 1 to 4 hours prior. | Standard deviation of glucose over 2 & 4 hours; Slope over 2 hours [33]. |

| Long-Term | Captures patient-specific control patterns. | % of time below 70 mg/dL or above 200 mg/dL; Number of "rebound" highs/lows [33]. |

| Snowball Effect | Captures accruing effects of glucose changes. | Sum of all increments/decrements in the last 2 hours; Maximum increase/decrease [33]. |

| Demographic | Static patient characteristics. | Age group, gender, diabetes duration, last HbA1c [33]. |

| Contextual | Temporal and behavioral data. | Time of day, day of week, insulin-on-board, carbohydrate-on-board [33]. |

3. Model Development:

- Parsimonious Feature Selection: Identify the most influential subset of features to avoid overfitting.

- Algorithm Selection: Implement a machine learning classifier (e.g., Logistic Regression, Random Forest, XGBoost).

- Outcome Definition: Define the prediction task as a binary classification: will the patient experience hypoglycemia (BG <70 mg/dL) within a specific time horizon (e.g., 30 or 60 minutes)? [33].

4. Model Evaluation:

- Assess model performance using Sensitivity and Specificity.

- Evaluate the added value of contextual data (insulin/carbs) by comparing model performance with and without these features [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Hypoglycemia Prediction and Rebound Hyperglycemia Research

| Item / Resource | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) System | Provides high-frequency, real-time interstitial glucose measurements. It is the primary data source for feature extraction in short-term prediction models and is critical for validating nocturnal hypoglycemia in Somogyi effect studies [3] [33]. |

| Electronic Health Record (EHR) Data | Serves as a source of longitudinal patient data for developing predictive models, including lab results, diagnoses, medications, and demographics. Essential for risk stratification and studying long-term outcomes [34] [35]. |

| Gradient Boosted Trees (XGBoost) | A powerful machine learning algorithm frequently used for structured data (like EHRs). It effectively handles complex, non-linear relationships between multiple clinical variables to predict events like hypoglycemia [34] [35]. |

| Random Forest (RF) Algorithm | An ensemble machine learning method that builds multiple decision trees. It has shown high accuracy and AUC in predicting hypoglycemia severity in hospitalized patients, often outperforming other models [35]. |

| Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) | A standardized, international medical terminology used for coding and analyzing adverse event reports, such as those in pharmacovigilance studies of insulin therapies [36]. |

| FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) | A public database containing spontaneous reports of adverse drug events. Used for post-marketing safety surveillance to identify potential rare or long-term adverse effects of antidiabetic drugs [36]. |

Signaling Pathway: Somogyi Effect Hypothesized Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the theorized physiological pathway of the Somogyi effect, as originally proposed.

Diagram 2: Somogyi Effect Pathway

Analytical Frameworks for Nocturnal Glucose Data in Large Cohorts

FAQs: Troubleshooting Common Research Challenges

Q1: What is the primary analytical challenge in confirming the Somogyi effect in large datasets? The primary challenge is differentiating the Somogyi effect from the more common Dawn Phenomenon, as both present with morning hyperglycemia. The Somogyi effect is theorized to be a rebound from nocturnal hypoglycemia, while the Dawn Phenomenon is attributed to a natural surge of counter-regulatory hormones in the early morning without a preceding hypoglycemic event [3] [1]. Analysis requires high-frequency nocturnal glucose data to confirm or rule out a hypoglycemic episode, which was often missing in older studies.

Q2: What does current evidence suggest about the prevalence of the Somogyi effect? Recent studies using Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) suggest the Somogyi effect is rare [2]. Research on Type 1 diabetic patients indicates that nocturnal hypoglycemia is more frequently associated with low morning glucose, not hyperglycemia, which refutes the classic Somogyi theory [1]. One study concluded that finding a low fasting glucose was a better indicator of nocturnal hypoglycemia than a rebound high [2].

Q3: What is a key methodological consideration when building predictive models for nocturnal hypoglycemia? A key consideration is the application of a decision-theoretic criterion to optimize the prediction threshold. This involves balancing the benefit of accurately predicting a true nocturnal hypoglycemia event against the cost of a false alarm, which could lead to unnecessary carbohydrate consumption and subsequent hyperglycemia [37]. This maximizes the clinical utility and net benefit of the algorithm.

Q4: How can researchers validate a predictive model for nocturnal hypoglycemia? Validation should occur in multiple stages. After initial training on a large dataset, the model should be tested on a separate, held-out validation set from a clinical trial. Furthermore, in-silico simulation using a virtual patient population provides a powerful tool to estimate the real-world impact and safety of the intervention (e.g., carbohydrate recommendation) before proceeding to costly clinical trials [37].

Experimental Protocols & Data Analysis

Protocol: Developing a Nocturnal Hypoglycemia Prediction Algorithm

This protocol is based on a study that used a Support Vector Regression (SVR) model to predict overnight minimum glucose [37].

1. Data Collection & Preprocessing:

- Data Sources: Utilize large-scale datasets combining CGM data (readings every 5 minutes) and insulin data (e.g., from insulin pumps). The training dataset used in the cited study included 22,804 valid nights from 124 individuals with T1D [37].

- Data Cleaning: Exclude nights with interventions that confound natural glucose fluctuations, such as meal consumption after 11 PM [37].

- Feature Engineering: Extract relevant features from CGM and insulin data leading up to bedtime. This likely includes metrics like rate of glucose change, total insulin delivered, and time in specific glucose ranges.

2. Model Training & Optimization:

- Algorithm Selection: Train a Support Vector Regression (SVR) model to predict the numerical value of the overnight minimum glucose [37].

- Decision Theory Application: Derive a binary classification threshold (e.g., hypoglycemia at <3.9 mmol/L) by applying a decision-theoretic criterion to maximize the expected net benefit of the prediction, balancing sensitivity and specificity [37].

3. Model Validation:

- Clinical Validation Set: Test the model's performance on a separate, prospectively collected dataset (e.g., from a 4-week clinical trial with 10 participants) [37].

- Performance Metrics: Evaluate using:

- Sensitivity and Specificity for predicting nocturnal hypoglycemia events.

- Correlation (R-value) between predicted and actual minimum glucose.

- Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE).

- Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC) [37].

4. In-Silico Impact Assessment:

- Virtual Patient Population: Use a validated computer simulation of a T1D population to test the algorithm's intervention strategy [37].

- Intervention Simulation: Simulate the effect of administering a carbohydrate snack at bedtime when the algorithm predicts hypoglycemia.

- Outcome Measurement: Quantify the potential reduction in nocturnal hypoglycemia and assess the impact on overall time-in-target glucose range [37].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of an SVR Model for Predicting Nocturnal Hypoglycemia

| Metric | Reported Performance | Context / Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 94.1% (95% CI: 71.3-99.9) | Predicting nocturnal hypoglycemia (<3.9 mmol/L) [37] |

| AUC-ROC | 0.86 (95% CI: 0.75-0.98) | Discriminatory power for hypoglycemia events [37] |

| Correlation (R) | 0.71 (P < 0.001) | Between predicted and actual minimum glucose [37] |

| Simulated Reduction | 77.0% (P = 0.006) | Reduction in nocturnal hypoglycemia with algorithm use [37] |

Table 2: Key Characteristics of Data Sets Used in Model Development

| Data Set | Subjects (n) | Nights of Data (n) | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Set | 124 | 22,804 | Model training and parameter optimization [37] |

| Validation Set 1 | 10 | 117 | Initial clinical validation [37] |

| Virtual Population | 20 | N/A | In-silico testing of intervention impact [37] |

Signaling Pathways and Conceptual Workflows

Theoretical Pathophysiology of the Somogyi Effect

Experimental Workflow for Predictive Model Development