Overcoming the Lag: Advanced Strategies for Continuous Glucose Monitoring Sensor Delay Compensation in Clinical Research and Drug Development

Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) has revolutionized metabolic research and therapy development, yet the inherent time lag between blood and interstitial fluid glucose measurements remains a critical challenge.

Overcoming the Lag: Advanced Strategies for Continuous Glucose Monitoring Sensor Delay Compensation in Clinical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) has revolutionized metabolic research and therapy development, yet the inherent time lag between blood and interstitial fluid glucose measurements remains a critical challenge. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the sources, implications, and compensation strategies for CGM sensor delay. We explore the physiological and technical foundations of delay, evaluate algorithmic and model-based compensation methodologies, and present optimization techniques for enhancing accuracy. The content synthesizes recent evidence on validation frameworks and comparative performance of leading CGM systems, offering a scientific foundation for improving clinical trial design, biomarker validation, and therapeutic intervention studies in diabetes and metabolic disorders.

The Physiology and Impact of CGM Sensor Delay: From Interstitial Fluid Dynamics to Clinical Consequences

Continuous Glucose Monitor latency originates from two primary sources: physiological lag and technical delay. The physiological lag, estimated at 6-10 minutes, stems from the time required for glucose to passively diffuse from blood capillaries into the interstitial fluid (ISF) where the sensor is located [1]. This delay can extend during rapid glucose changes, such as after a meal or insulin administration. The technical delay encompasses the time for glucose diffusion through sensor membranes, the electrochemical reaction time with the glucose oxidase enzyme, and the application of calibration algorithms to smooth the raw sensor signal [1]. Combined, these factors create a total time lag that typically ranges between 10-15 minutes compared to plasma glucose measurements [2] [1].

FAQ: How can researchers quantitatively measure and characterize CGM latency?

Researchers can employ standardized protocols to measure the total CGM latency. One key method involves conducting Oral Glucose Tolerance Tests (OGTT) while collecting paired plasma glucose (PG) and CGM measurements at regular intervals [2]. Two analytical approaches for quantifying the delay from this data are:

- MARD Minimization: The interstitial glucose measurements are systematically shifted in time (e.g., by 5, 10, and 15 minutes), and the time shift that results in the minimum Mean Absolute Relative Difference (MARD) between the CGM and PG values is identified as the total delay [2].

- Minimum Deviation Match: For each PG measurement, the CGM value that provides the smallest absolute difference within a plausible delay window (e.g., 0-15 minutes after the blood draw) is identified. The average of these optimal time shifts across all data points represents the delay [2]. Studies suggest this method may be more suitable due to less variability in timing glucose peaks [2].

The table below summarizes performance data from a latency characterization study using the SiJoy GS1 CGM during an OGTT [2].

Table 1: CGM Performance and Latency Data from an OGTT Study (n=129)

| Metric | Result | Context/Description |

|---|---|---|

| Overall MARD | 8.01% (± 4.9%) | Measured during the fasting phase [2]. |

| Consensus Error Grid | 89.22% in Zone A; 100% in Zones A+B | Indicates clinical accuracy [2]. |

| Suggested Delay (MARD Minimization) | 15 minutes | Identified at 30 minutes post-OGTT [2]. |

| Suggested Delay (Min. Deviation Match) | 10 minutes | Identified as the average delay time [2]. |

FAQ: What experimental protocols are used to evaluate CGM latency?

A detailed protocol for evaluating CGM sensor performance and latency is outlined below. This methodology is adapted from a clinical study performance evaluation [2].

Protocol: Evaluating CGM Latency via Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT)

- Objective: To assess the performance of a CGM system and characterize the time lag between plasma glucose (PG) and CGM measurements during rapid glucose excursions.

- Study Design: Cross-sectional observational study.

- Participants:

- Number: 129 participants with complete OGTT records [2].

- Inclusion Criteria: Healthy adults (aged 20-60 years), non-smokers, no history of diabetes, no recent medication use, blood pressure < 140/90 mmHg [2].

- Key Demographic Characteristics: Mean age 37.6 (± 11.2) years; 51.9% female, 48.1% male [2].

- Pre-Test Procedures:

- OGTT Execution:

- Data Management & Analysis:

- PG measurements are aligned with CGM values recorded at the same timestamp.

- Apply the MARD Minimization and Minimum Deviation Match methods to estimate the total time delay as described in FAQ #2.

- Calculate overall MARD and Consensus Error Grid analysis to determine clinical accuracy.

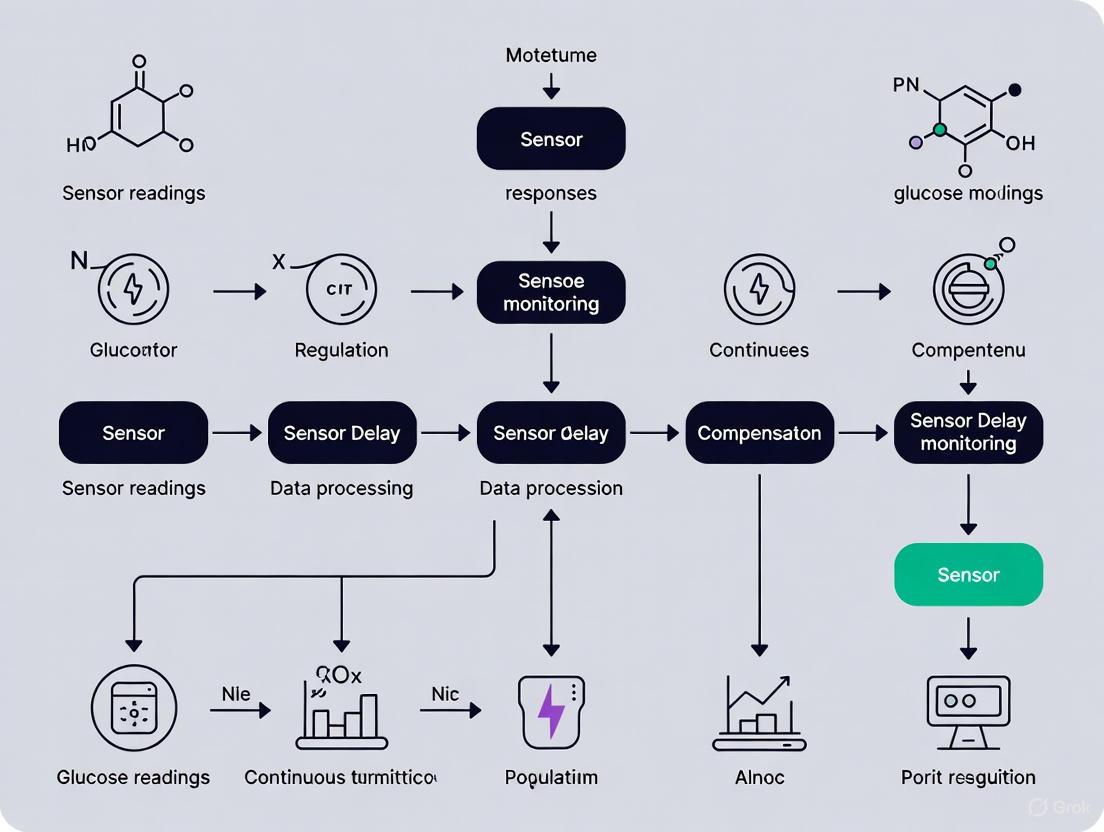

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for CGM Latency Characterization

FAQ: What are the clinical implications of CGM latency, especially during rapid glucose changes?

The intrinsic latency of CGM systems has direct clinical implications for data interpretation and patient management. During periods of rapidly changing glucose levels (e.g., postprandially or after insulin administration), the discrepancy between plasma glucose and the delayed interstitial glucose reading can be significant [1]. For instance, if blood glucose is dropping rapidly into a hypoglycemic range, the CGM value may still appear normal, potentially delaying critical alerts and interventions [1]. This is a key limitation that compensation algorithms aim to address. Modern CGM systems incorporate predictive alerts for upward and downward trends to partially mitigate this risk, providing warnings before severe hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia occurs [1].

FAQ: What novel computational approaches are being developed to compensate for CGM latency?

Emerging research focuses on using artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning models to compensate for latency and improve glucose prediction. One innovative approach is the development of a "virtual CGM" [3]. This framework utilizes a deep learning model, specifically a bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network with an encoder-decoder architecture, to infer current and future glucose levels [3]. Crucially, this model can operate independently of prior CGM readings during inference by leveraging comprehensive "life-log" data as input, including [3]:

- Dietary intake (calories, macronutrients)

- Physical activity (MET values, step counts)

- Temporal data (time of day)

This approach demonstrates the potential to maintain glucose monitoring during periods of CGM signal dropout or to support intermittent monitoring scenarios, effectively compensating for physical sensor limitations and delays [3].

Diagram: "Virtual CGM" Deep Learning Framework for Latency Compensation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for CGM Latency Research

| Item / Solution | Function in Research Context |

|---|---|

| CGM Systems (e.g., SiJoy GS1, Dexcom G7) | The primary device under test; provides continuous interstitial glucose measurements for comparison against gold standard methods [2] [3]. |

| Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) Kit | A standardized provocative test (typically 75g glucose) to induce rapid glycemic excursions, essential for characterizing sensor performance and latency under dynamic conditions [2]. |

| Enzymatic Plasma Glucose Assays | Gold-standard reference method for measuring glucose concentration in plasma samples obtained during venipuncture; used for calibrating and validating CGM accuracy [2]. |

| Biocompatible Skinfold Calipers | Tools to measure subcutaneous fat thickness at sensor insertion sites, a potential variable affecting physiological glucose diffusion time and sensor signal stability. |

| Data Analysis Software (e.g., Python with scikit-learn, TensorFlow/PyTorch) | Platforms for implementing MARD calculations, error grid analysis, and developing advanced machine learning models (e.g., LSTM networks) for latency prediction and compensation [2] [3]. |

This technical support document provides evidence-based troubleshooting guidance for researchers investigating the time lag between plasma and interstitial glucose dynamics. The physiological delay in glucose transport from the vascular compartment to the interstitial space is a critical factor affecting the accuracy of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) systems. This guide synthesizes findings from recent Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) studies to help you design better experiments and optimize sensor delay compensation algorithms.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the typical physiological time lag between plasma and interstitial glucose? The intrinsic physiological time lag—the time required for glucose to travel from blood capillaries to the interstitial fluid—is generally shorter than the total lag observed with CGM systems. Direct measurement using glucose tracers and microdialysis in fasted, healthy adults has found this physiological delay to be approximately 5-6 minutes [4]. Another study using multitracer plasma and interstitium data reported an "equilibration time" of 9.1 and 11.0 minutes in healthy and type 1 diabetic subjects, respectively [5]. The total observed lag during an OGTT is often longer due to additional technical factors.

FAQ 2: Why does the observed lag during an OGTT often exceed the physiological lag? The lag reported in OGTT studies (often 10-15 minutes) represents the combined effect of the physiological lag and technical delays introduced by the CGM system itself [2]. Technical factors include the sensor's electrochemical response time and the signal processing algorithms (such as filtering) applied to raw CGM data to reduce noise [5] [6]. This is why the total lag is greater than the pure physiological transport time.

FAQ 3: How does the plasma-interstitium glucose relationship change during rapid glucose shifts? The agreement between plasma and interstitial glucose values is not constant. During the dynamic phases of an OGTT (e.g., at 30 and 60 minutes), CGM devices tend to underestimate plasma glucose levels, with mean differences of -1.1 mmol/L at 30 min and -1.4 mmol/L at 60 min reported in one study [7]. This phenomenon, where CGM underestimates high plasma glucose values, can lead to an underestimation of hyperglycemic excursions [7].

FAQ 4: Is the time lag consistent across all patient populations? No, the lag can vary based on population characteristics. For instance, one study noted a proportional bias at 0 and 120 minutes of the OGTT, meaning the difference between CGM and OGTT values increased as the mean glucose concentration increased [7]. Furthermore, glucose kinetics may differ between healthy individuals and those with diabetes [5].

FAQ 5: Can CGM replace plasma glucose measurements for assessing glucose tolerance? Current evidence suggests caution. One study in a prediabetic population concluded that due to poor agreement with wide 95% limits of agreement and proportional bias, the potential for using CGM alone to assess glucose tolerance is questionable [7]. However, other research indicates that CGM glucose can be a viable alternative for calibrating personalized models of glucose-insulin dynamics, with the advantage of being minimally invasive [8].

Table 1: Reported Time Lags Between Plasma and Interstitial Glucose

| Study Population | Experimental Condition | Reported Time Lag (minutes) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Adults [4] | Fasting; Intravenous Tracer Bolus | 5.3 - 6.2 | Direct measurement of physiological glucose transport using tracers and microdialysis. |

| Healthy & T1DM Subjects [5] | Fasting; Multitracer & Microdialysis | 9.1 (Healthy), 11.0 (T1DM) | Model-derived "equilibration time." Suggests a slightly longer lag in T1DM. |

| Prediabetes & Overweight [7] | OGTT; CGM (Medtronic iPro2) | Best match found within a 0-15 min window | CGM values were consistently below OGTT values during post-challenge period. |

| Healthy Adults [2] | OGTT; CGM (SiJoy GS1) | 10-15 (Method-dependent) | One minimization method suggested a 15-min delay; another proposed 10 min. |

Table 2: Mean Differences Between CGM and OGTT Plasma Glucose Values During an OGTT in Prediabetes [7]

| OGTT Time Point (minutes) | Mean Difference (CGM - OGTT) mmol/L (SD) |

|---|---|

| 0 (Fasting) | 0.2 (0.7) |

| 30 | -1.1 (1.3) |

| 60 | -1.4 (1.8) |

| 120 | -0.5 (1.1) |

Experimental Protocols for Lag Assessment

Protocol 1: Lag Assessment During a Standard OGTT

This protocol is suitable for evaluating the combined physiological and technical lag of a CGM system in a clinical setting [7] [2].

- Participant Preparation: Participants should fast for ≥10 hours overnight. Avoid vigorous exercise, illness, and medications that affect glucose tolerance for at least 3 days prior to the test.

- Sensor Insertion: Insert the CGM sensor (e.g., on the abdomen or posterior upper arm) at least 48 hours before the OGTT to allow the sensor to stabilize and the local tissue trauma to subside [2].

- OGTT Execution:

- Collect a baseline venous blood sample (t=0 min).

- Administer a standardized 75g glucose drink within 5 minutes.

- Collect subsequent venous plasma samples at key time points (e.g., 30, 60, 120 minutes post-load).

- CGM Data Collection: Ensure the CGM device is set to record glucose concentrations every 5 minutes throughout the OGTT.

- Calibration: Calibrate the CGM device according to the manufacturer's instructions using capillary or plasma glucose values. Note the timing of calibration as it can affect accuracy.

- Data Alignment and Analysis:

- Minimum Deviation Match: For each post-challenge plasma glucose value, find the CGM value within a 0-15 minute window that results in the smallest absolute difference. Record the time difference for each match [7] [2].

- MARD Minimization: Shift the entire CGM time-series by fixed intervals (e.g., 5, 10, 15 minutes) and calculate the Mean Absolute Relative Difference (MARD) between the shifted CGM values and the plasma glucose values at the corresponding OGTT time points. The shift with the lowest MARD indicates the optimal lag compensation [2].

Protocol 2: Advanced Tracer Protocol for Physiological Lag

This complex protocol uses glucose tracers to isolate the physiological component of the lag [5] [4].

- Tracer Administration: Intravenously administer a bolus of stable or radioactive glucose tracers (e.g., [1-13C] glucose, [6,6-2H2] glucose).

- Simultaneous Sampling: Frequently and simultaneously collect timed samples of arterialized venous plasma and subcutaneous interstitial fluid using a technique like microdialysis with multiple catheters.

- Microdialysis Considerations: Account for the dead space and time delay inherent in the microdialysis system itself (e.g., a 6.2-minute transit time correction may be required) [4].

- Biochemical Analysis: Analyze plasma and microdialysate samples for glucose tracer enrichments using mass spectrometry.

- Kinetic Modeling: Model the plasma-to-ISF glucose kinetics using linear time-invariant compartmental models. The "equilibration time" (time constant) of the model characterizes the intrinsic delay [5].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Glucose pathway from ingestion to CGM signal.

Diagram 2: Workflow for OGTT-based CGM lag assessment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Plasma-Interstitium Glucose Studies

| Item | Function / Application | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitors | Measures interstitial glucose concentrations at regular intervals (e.g., every 5 mins). | Medtronic iPro2 with Enlite sensor [7], SiJoy GS1 [2], DexCom, Abbott systems. |

| Glucose Tracers | Allows direct tracking of glucose kinetics between compartments without isotopic effects. | Stable isotopes: [1-13C] glucose, [6,6-2H2] glucose [5] [4]. |

| Microdialysis System | Directly samples interstitial fluid from subcutaneous tissue for quantitative analysis. | CMA microdialysis catheters (e.g., CMA 63) and perfusion pumps [4]. |

| Enzymatic Assays | Precisely measures glucose concentrations in plasma and microdialysate samples. | Hexokinase method (high precision) [9], Glucose Oxidase method. |

| Calibration Glucometer | Provides reference blood glucose values for CGM calibration during wear. | Contour XT glucometer [7]. |

| Mass Spectrometry | Measures very low concentrations and enrichment of glucose tracers in plasma and ISF. | Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) [4]. |

FAQ: Understanding Sensor Delay

What is sensor delay, and what causes it? Sensor delay, or lag time, refers to the phenomenon where Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) readings from interstitial fluid (ISF) lag behind blood glucose meter readings from capillary blood. This occurs for two main reasons:

- Physiological Delay: Glucose moves from the blood vessels into the interstitial fluid, a process that takes time, especially during periods of rapid glucose change [10].

- Technical Delay: The sensor itself requires time to process the glucose signal from the interstitial fluid [11]. The combined delay is typically up to 15 minutes [10] [11].

Why is sensor delay a critical concern for hypoglycemia detection? Sensor delay can postpone the recognition of a rapidly falling or low blood glucose event. A CGM might display a near-normal glucose value while the actual blood glucose level is already at or below the hypoglycemic threshold (≤4 mmol/L) [12] [10]. This lag can delay corrective action, increasing the risk and duration of a hypoglycemic episode, which is a leading cause of hospitalization in vulnerable populations like long-term care residents [12].

How does sensor delay affect core glycemic metrics like Time in Range (TIR)? Sensor delay can introduce inaccuracies into glycemic variability metrics. During rapid glucose transitions, the delay means CGM data does not reflect the real-time glycemic state. This can lead to:

- Underestimation of Hypoglycemia: The duration and severity of hypoglycemic events may be inaccurately represented, affecting the "Time Below Range" metric [12].

- Inaccurate Glycemic Excursion Mapping: The precise timing and amplitude of glucose peaks and troughs are shifted, which can skew the calculation of Time in Range and Glucose Management Indicator (GMI) [11].

Troubleshooting Guide: Mitigating the Impact of Sensor Delay in Research

Issue: Hypoglycemia events detected by CGM are not aligned with clinical observations or blood glucose measurements. Solution:

- Validate with Blood Glucose Meter (BGM): Always corroborate CGM readings below 4 mmol/L or during periods of rapid change with a fingerstick test from a calibrated BGM [13].

- Understand Lag Dynamics: Recognize that the delay is most pronounced when glucose levels are changing rapidly. Inform study protocols to account for this inherent limitation [10].

- Analyze Trend Arrows: Use the CGM's trend arrows (e.g., ↓→) as a more actionable indicator of glucose direction than a single, potentially lagging, glucose value.

Issue: Experimental data shows a systematic time shift between CGM and plasma glucose (PG) during an Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT). Solution: This is an expected physiological phenomenon. Implement a data processing methodology to quantify and compensate for the delay [11].

- MARD Minimization Method: Shift the CGM-derived ISF glucose measurements by set intervals (e.g., 5, 10, 15 minutes) and calculate the Mean Absolute Relative Difference (MARD) at each interval against PG. The optimal delay is determined by the shift that produces the minimum MARD [11].

- Minimum Deviation Match Method: Align each PG measurement with the CGM value that provides the smallest absolute difference within a plausible delay window (e.g., 0-15 minutes) after the blood draw. This method can be advantageous when there is high variability in individual glucose peak times [11].

Quantitative Data on Sensor Performance and Delay

Table 1: Clinical Performance of a CGM Sensor (SiJoy GS1) During OGTT [11]

| Performance Metric | Result (Fasting Phase) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| MARD | 8.01% (± 4.9) | Lower MARD indicates superior sensor accuracy. |

| 20/20% Consensus | 96.6% | Percentage of sensor values within 20% of reference value or within 20 mg/dL for values <100 mg/dL. |

| Error Grid (Zone A) | 89.22% | Values indicating clinically accurate readings. |

| Error Grid (Zone A+B) | 100% | Values indicating clinically acceptable readings. |

Table 2: Impact of CGM Implementation in Long-Term Care (LTC) [12]

| Metric | Baseline (Fingerstick) | Post-CGM Implementation | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing Time per Test | 5.1 minutes | 3.1 minutes | 40% reduction |

| Total Glucose Readings | 19,438 | 35,971 | Increased frequency |

| Detected Hypoglycemic Events | 88 | 1,049 | 12-fold increase |

Experimental Protocols for Delay Compensation Research

Protocol: Quantifying Time Lag During an Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) [11]

Objective: To evaluate the total time delay (physiological and technical) between plasma glucose (PG) and interstitial fluid glucose (ISFG) measured by CGM during standardized glucose excursions.

Materials:

- CGM system (e.g., SiJoy GS1, FreeStyle Libre 2, Dexcom G6)

- Participants (e.g., healthy adults or individuals with prediabetes/diabetes)

- Standard 75g glucose solution for OGTT

- Venous blood collection equipment

- Laboratory chemistry analyzer for PG measurement

Methodology:

- Sensor Placement: Apply the CGM sensor to the participant's posterior upper arm at least 48 hours before the OGTT to ensure stabilization.

- OGTT Procedure: After an overnight fast, participants ingest the 75g glucose solution within 10 minutes.

- Blood Sampling: Collect venous blood samples for PG measurement at predefined intervals (e.g., 0, 30, 60, 120, and 180 minutes).

- Data Collection: Record concurrent CGM values every 5 minutes throughout the test.

- Data Analysis: Apply the MARD Minimization or Minimum Deviation Match method (described above) to the paired PG-CGM data sets to calculate the optimal time delay.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

CGM Sensor Delay Pathway

OGTT-Based Sensor Delay Evaluation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for CGM Delay Compensation Research

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| CGM Systems (e.g., Dexcom G6, Abbott Libre 2, SiJoy GS1, Medtronic Guardian) | The primary devices under investigation for their delay characteristics and accuracy metrics (MARD) [12] [11]. |

| Calibrated Blood Glucose Meter (BGM) | Provides the point-of-care reference value for validating CGM readings, especially during hypoglycemia or rapid glucose changes [13]. |

| Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) Kit | A standardized tool (75g glucose) for creating a controlled and reproducible glycemic excursion to study sensor performance dynamics [11]. |

| Laboratory Plasma Glucose Analyzer | The gold-standard method for measuring venous plasma glucose, used as the primary reference for assessing CGM accuracy and calculating time lag [11]. |

| Data Analysis Software (e.g., Python, R, MATLAB) | Used to implement and run delay compensation algorithms (MARD minimization, deviation matching) on synchronized PG and CGM data sets [11]. |

For researchers developing non-adjunctive glucose monitoring systems—where patients make therapy decisions without confirmatory fingerstick testing—establishing robust accuracy thresholds is paramount. The Mean Absolute Relative Difference (MARD) serves as the primary benchmark for quantifying Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) sensor performance [14]. A lower MARD value indicates higher accuracy, with a MARD under 10% generally considered acceptable for insulin dosing decisions [14]. However, MARD is an average value and may mask clinically significant inaccuracies at glycemic extremes (hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia), necessitating complementary metrics for a complete performance evaluation [14].

Regulatory distinctions critically impact therapy development. Devices are categorized as either adjunctive (requiring confirmation via finger-prick testing before insulin dosing) or non-adjunctive (approved for independent insulin-dosing decisions) [14]. The regulatory bar is higher for non-adjunctive use. In the US, this typically involves the FDA's "integrated CGM" (iCGM) designation and Class III pre-market approval, which demands stricter criteria for accuracy, reliability, and interoperability [14]. CE or UKCA marking, while necessary for market access in Europe, does not itself guarantee a device's suitability for non-adjunctive insulin dosing [14].

Essential Accuracy Metrics & Performance Data

Beyond MARD, a comprehensive sensor evaluation requires additional metrics that provide a more nuanced view of clinical accuracy, especially in hypoglycemic and hyperglycemic ranges critical for patient safety.

Table 1: Key CGM Accuracy Metrics for Non-Adjunct Use Evaluation

| Metric | Definition | Clinical Significance for Therapy Development |

|---|---|---|

| MARD | Mean Absolute Relative Difference; the average variance between CGM readings and reference values [14]. | Primary benchmark; a value <10% is a common target for insulin-dosing systems [14]. |

| 20/20 Accuracy | Percentage of CGM values within ±1.1 mmol/L (±20 mg/dL) of reference at glucose <5.5 mmol/L, or within ±20% at glucose ≥5.5 mmol/L [14]. | Measures clinically accurate readings; higher percentages indicate greater reliability for safe dosing. |

| 40/40 Accuracy | Percentage of CGM values within ±2.2 mmol/L (±40 mg/dL) of reference at glucose <5.5 mmol/L, or within ±40% at glucose ≥5.5 mmol/L [14]. | Identifies readings with larger errors that could lead to significant insulin dosing mistakes. |

The following diagram illustrates the foundational workflow for establishing CGM accuracy, integrating these core metrics and regulatory considerations.

CGM Accuracy Evaluation Workflow

Researcher FAQs on CGM Performance

Q: What are the internationally accepted criteria for a robust CGM performance study design? A: A trustworthy study design for non-adjunctive use should meet five key criteria endorsed by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and the International Federation for Clinical Chemistry (IFCC) Working Group [14]:

- Peer-reviewed data

- Population: Inclusion of more than 70% of participants with type 1 diabetes.

- Challenges: Use of meal and insulin challenges to test performance under real-world conditions.

- Range: Evaluation across a broad glucose range (typically 2.2–22.2 mmol/L).

- Episodes: Inclusion of both hypoglycemic and hyperglycemic episodes.

Q: Why is MARD alone an insufficient metric for certifying a device for non-adjunctive use? A: While MARD is a valuable average, it can obscure critical performance issues. A device might have a low overall MARD yet perform poorly in the hypoglycemic range, where accurate readings are most critical for preventing severe adverse events. Therefore, regulators and developers must analyze metrics like 20/20 and 40/40 accuracy, which provide a clearer picture of performance at the clinically critical extremes [14].

Q: What are common real-world failure modes that performance studies should seek to replicate? A: Beyond controlled clinical settings, researchers must account for scenarios reported by users [15] [16]:

- Compression Lows: Falsely low readings caused by pressure on the sensor (e.g., during sleep), which can lead to unnecessary carbohydrate intake or ignored alarms [15] [16].

- Sensor Displacement/Adhesive Failure: Physical issues leading to sensor detachment or erroneous data [15].

- Connectivity Issues: Bluetooth drops or smartphone notification settings that prevent critical alerts from reaching the user [15].

- Algorithmic Drift: Sensor inaccuracies that develop over the wear period due to manufacturing defects or body chemistry interactions [15].

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimental & Device Errors

This guide addresses specific issues researchers might encounter during bench testing and clinical validation of CGM systems.

Table 2: Troubleshooting CGM Research & Development Challenges

| Problem Scenario | Root Cause | Investigation & Resolution Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Unexplained MARD Increase | Sensor manufacturing batch defects, unstable enzyme chemistry, or biocompatibility issues (foreign body response). | 1. Lot Analysis: Compare MARD by sensor lot number. 2. Accelerated Aging: Test sensor stability under various environmental conditions. 3. Histology: In animal studies, examine tissue surrounding the sensor for inflammation. |

| Compression Lows in Data | Physical pressure on sensor site altering interstitial fluid dynamics [15] [16]. | 1. Algorithm Filtering: Develop and validate algorithms to detect and flag pressure-artifact signals. 2. Placement Guidance: Define and validate optimal anatomical placement sites to minimize pressure in protocols. 3. Subject Reporting: Implement robust participant reporting for sleep position and physical activity. |

| Connectivity Gaps in Data Stream | Bluetooth interference, receiver hardware failure, or software bugs in data handling [15]. | 1. Signal Mapping: Document signal strength and drop-out locations in clinical settings. 2. Hardware Diagnostics: Implement built-in receiver diagnostics to log connection health. 3. Data Bridging: Develop algorithms to intelligently bridge short data gaps. |

| Inaccurate Hyperglycemia Readings | Sensor "drift" due to biofouling, delayed interstitial fluid (ISF) equilibrium, or calibration errors. | 1. ISF Lag Characterization: Quantify plasma-to-ISF lag time under hyperglycemic clamps. 2. Dynamic Calibration: Investigate multi-point calibration models that account for rate-of-change. 3. Reference Verification: Ensure frequent and accurate reference measurements (e.g., YSI) during high glucose periods. |

The signaling pathway below outlines the logical relationship between a CGM reading error and its potential downstream consequences, which is vital for risk assessment in therapy development.

CGM Error Consequence Pathway

Experimental Protocols for Sensor Validation

Protocol 1: Assessing Clinical Accuracy Against Reference Standards Objective: To determine the MARD, 20/20, and 40/40 accuracy of a CGM system across the glycemic range. Methodology:

- Participant Cohort: Recruit a minimum of 100 subjects, with over 70% having type 1 diabetes to ensure testing under conditions of significant glycemic variability [14].

- Reference Method: Use a clinically approved reference method such as a YSI blood analyzer or frequent capillary blood glucose testing with a validated meter.

- Clamp Protocol: Implement glucose challenges, including meal tests and insulin-induced hypoglycemia, to generate a wide range of glucose values (target: 2.2 to 22.2 mmol/L) [14].

- Data Pairing: Collect a minimum of 150-200 paired data points (CGM vs. reference) per subject over the sensor's wear period.

- Analysis: Calculate overall MARD, MARD by glucose range, and the percentages of points meeting 20/20 and 40/40 criteria [14].

Protocol 2: Investigating Sensor Delay (ISF Lag) Compensation Objective: To characterize and model the physiological time lag between blood and interstitial fluid glucose. Methodology:

- Hyperglycemic Clamp: Establish a steady-state hyperglycemic level in a clinical research unit.

- High-Frequency Sampling: Measure plasma glucose and CGM values simultaneously at 1-5 minute intervals during the clamp's upward ramp and subsequent decline.

- Time-Series Analysis: Use cross-correlation analysis to determine the average time lag between plasma and ISF glucose trajectories.

- Algorithm Development: Train a predictive compensation algorithm (e.g., using Kalman filtering or a machine learning model) on one dataset and validate it on a separate hold-out dataset to improve real-time accuracy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for CGM Performance and Delay Research

| Research Tool | Function in CGM Development |

|---|---|

| YSI 2300 STAT Plus Analyzer | The gold-standard reference instrument for measuring plasma glucose in clinical studies, providing the benchmark for MARD calculation [14]. |

| Glucose Clamp Apparatus | A system for performing hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic or hyperglycemic clamps, allowing controlled manipulation of blood glucose to test sensor performance and lag [17]. |

| Continuous Glucose Monitoring Simulator (e.g., UVA/Padova Simulator) | A validated computer model of the glucose-insulin system that allows for in-silico testing of sensor algorithms and lag compensation methods without initial human trials. |

| Biofouling Characterization Materials | Tools (e.g., ELISA kits, histology stains) to analyze protein adsorption and inflammatory cell attachment on explanted sensors, investigating causes of signal drift. |

| Kalman Filter / Machine Learning Framework | A software framework (e.g., in Python/MATLAB) for developing and testing predictive algorithms that compensate for sensor noise and physiological ISF lag. |

This technical support center is designed for researchers and scientists investigating the interindividual variability in metabolic rate and physiology, with a specific focus on its implications for continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) sensor delay compensation. A profound understanding of these biological variabilities is critical for developing next-generation CGM systems and robust compensation algorithms. The guides and FAQs that follow address common experimental challenges, provide standardized protocols for measuring key metabolic parameters, and offer resources for troubleshooting CGM data acquisition in a research setting. The core premise is that the delay characteristics observed in CGM signals are not merely a technological artifact but are significantly influenced by the underlying physiological heterogeneity of the human body.

Researcher FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is understanding interindividual variability in metabolic rate crucial for CGM delay compensation research?

Interindividual variability in metabolic rate signifies that the same physiological event (e.g., a glucose bolus) will be processed at different rates by different individuals. This metabolic heterogeneity is a primary source of the variability observed in the physiological lag between blood glucose and interstitial fluid glucose. Compensation algorithms that assume a fixed population-wide delay will therefore be inherently inaccurate for a significant portion of users. Research into this variability allows for the development of personalized delay models that can significantly improve CGM accuracy [18].

FAQ 2: What are the primary physiological factors contributing to CGM sensor delay?

The sensor delay is a composite of several physiological processes:

- Physiological Lag: The time required for glucose to diffuse from capillaries into the interstitial fluid (ISF). This is influenced by local blood flow, capillary wall permeability, and the metabolic rate of the subcutaneous tissue.

- Sensor Response Time: The electrochemical reaction time of the sensor itself, which is typically a constant but can be influenced by local tissue reactions that vary between individuals.

- Data Processing and Smoothing: The algorithmic processing applied by the CGM system to raw sensor data. The interplay of these factors means that the total observed delay is not a static value but can fluctuate within and between individuals based on their unique and dynamic physiology [19].

FAQ 3: How can I control for intra-individual variation in metabolic rate during my experiments?

Intra-individual variation in Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) can be significant. Key experimental controls include:

- Strict Fasting Protocol: Ensure subjects are in a true post-absorptive state. Non-compliance with fasting can increase the within-subject coefficient of variation (CV) in BMR measurements [20].

- Standardize Pre-Test Activity: Monitor and, if possible, standardize physical activity levels for 24-72 hours prior to metabolic testing using tools like tri-axial accelerometers. While one study found BMR measurements were reproducible despite day-to-day activity variations, controlling for this variable reduces unexplained noise [20].

- Regular Equipment Calibration: Conduct regular function checks of metabolic measurement systems (e.g., ventilated-hood systems) to account for within-machine variability [20].

FAQ 4: My research CGM system is experiencing frequent signal loss. What are the common causes?

Signal loss interrupts the continuous data stream, which is fatal for delay characterization studies. Common causes include:

- Bluetooth Connectivity Issues: The display device (smartphone/receiver) is too far from the sensor (beyond ~20 feet) or has obstructions (walls, water) between them [21] [22].

- Device-Specific Software: Outdated CGM app versions may not be compatible with new transmitter serial numbers or operating systems (e.g., iOS/Android updates) [23] [22].

- Incorrect Device Settings: Features like "Locked and Hidden apps" in iOS 18 can block critical glucose alarms and data transmission [22].

Step-by-Step Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent CGM Sensor Accuracy During a Clinical Study

| Step | Action | Rationale & Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify sensor code entry and warm-up period completion. | An incorrect sensor code or interrupted warm-up can compromise factory calibration. The G6 and G7 are factory-calibrated and should not require user calibration if the code is entered correctly [23] [24]. |

| 2 | Inspect the sensor insertion site for pressure (pressure-induced sensor attenuation) or irritation. | Mechanical pressure on the sensor can cause falsely low readings. Ensure the site is free from tight clothing or positions that cause pressure during sleep or rest [23]. |

| 3 | Cross-validate with a reference method (e.g., Yellow Springs Instrument). | If readings seem inaccurate, use a high-quality, calibrated reference method to establish ground truth. Note that temporary mismatches can occur, but values should converge over time [23]. |

| 4 | Check for confounding medications. | Unlike earlier models, Dexcom G6 and G7 are not affected by common NSAIDs like ibuprofen, but it is critical to verify the latest drug-interaction charts for the specific sensor model in use [21]. |

| 5 | Document and report the sensor. | For a systematic study, note the sensor's serial number and session details. Manufacturers have replacement policies for confirmed sensor failures, which can be tracked for quality control in your research [21] [23]. |

Problem: Connectivity and Data Transmission Failure to Research Display Device

| Step | Action | Rationale & Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Confirm proximity and clear line-of-sight between sensor and display device. | Bluetooth has a limited range (~20 feet) and can be blocked by physical obstacles. Keep the devices in close, unobstructed proximity [22]. |

| 2 | Toggle device Bluetooth off and on. | This resets the Bluetooth stack and can often re-establish a lost connection [22]. |

| 3 | Restart the display device (smartphone/receiver). | A device reboot clears temporary software glitches that may be preventing communication [22]. |

| 4 | Update the CGM application to the latest version. | Older app versions may lack compatibility with new transmitters or operating systems. Always use the latest verified research-compatible version [23]. |

| 5 | Check for operating system compatibility. | Before updating phone OS (e.g., to iOS 18), consult the manufacturer's compatibility guide. New OS features can interfere with app functionality and alarm delivery [22]. |

Quantitative Data & Sensor Specifications

CGM Sensor Performance Metrics for Research Selection

The following table summarizes key performance characteristics of common CGM sensors, which are critical for designing experiments on delay compensation. Accuracy, measured by MARD, is a primary differentiator.

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics of Dexcom CGM Sensors for Research Applications

| Sensor Model | MARD (%) | Warm-up Time (min) | Sensor Life (days) | Calibration Required? | Key Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dexcom G7 | 8.2 [24] | 30 [24] | 10.5 | No | Ideal for studies requiring the lowest intrinsic sensor delay and highest accuracy. |

| Dexcom G6 | 9.0 [24] | 120 [24] | 10 | No | The established benchmark; extensive literature for validation and comparison studies. |

| Dexcom ONE+ | Not specified (Marketed as "most accurate") [24] | Not specified | 10 | No | A cost-effective option for large-scale population studies on variability. |

Quantitative Data on Metabolic Rate Variability

Understanding the expected range of metabolic variability is essential for powering studies and interpreting results.

Table 2: Measured Variability in Human Metabolic Parameters

| Metabolic Parameter | Type of Variability | Measured Coefficient of Variation (CV) | Key Influencing Factors | Experimental Control Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) | Intra-individual | 3.3% (range 0.4% - 7.2%) [20] | Fasting status, physical activity prior to testing, machine variability [20]. | Strict fasting, pre-test activity monitoring, regular equipment calibration [20]. |

| Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) | Interindividual | Can be "significant" after controlling for known factors [18] | Body composition, age, sex, genetic factors, thyroid function [18]. | Precise phenotyping of participants (e.g., DEXA scans) for use as covariates in analysis. |

| Total Daily Energy Expenditure | Interindividual | Significant variability exists beyond BMR [18] | Diet-induced thermogenesis, exercise, non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) [18]. | Standardized diet and activity protocols in controlled settings. |

Standardized Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Assessing Intra-Individual BMR Variation

Objective: To reliably measure the within-subject variation in Basal Metabolic Rate using a standard out-patient protocol. Materials: Ventilated-hood indirect calorimetry system, tri-axial accelerometer, subject questionnaire. Methodology:

- Participant Preparation: Participants spend the night before testing at home and transport themselves to the lab. They must fast for a minimum of 12 hours prior to the measurement.

- Pre-Test Activity Monitoring: Participants wear a tri-axial accelerometer for the 3 days preceding each BMR measurement to quantify habitual physical activity.

- BMR Measurement: Upon arrival, the subject rests in a supine position in a thermoneutral, quiet, and dimly lit room for 30 minutes. BMR is then measured via indirect calorimetry for a minimum of 30 minutes, following manufacturer guidelines.

- Replication: The measurement is repeated three times with 2-week intervals to assess variability.

- Data Validation: Exclude measurements from analysis if protocol non-compliance is reported (e.g., non-fasting). Correct for within-machine variability based on regular system checks [20].

Protocol for Correlating Metabolic Phenotypes with CGM Delay

Objective: To characterize the relationship between an individual's metabolic phenotype and the observed physiological delay in CGM readings. Materials: CGM system (e.g., Dexcom G7), reference blood glucose analyzer (e.g., YSI), indirect calorimeter, food and exercise standardization materials. Methodology:

- Participant Phenotyping:

- Measure BMR via indirect calorimetry as in Protocol 4.1.

- Conduct body composition analysis (e.g., DEXA or BIA).

- Administer an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) with frequent venous blood sampling to establish individual glucose metabolism dynamics.

- CGM Data Collection: Apply a CGM sensor to each participant according to manufacturer instructions. Simultaneously, collect frequent capillary or venous blood samples over a 24-48 hour period that includes standardized meals and activities for reference glucose values.

- Delay Calculation: For each meal or glucose excursion, calculate the physiological lag by cross-correlating the CGM trace with the reference blood glucose trace to find the time shift that produces the maximum correlation.

- Data Analysis: Use multiple regression analysis to model the calculated delay time as a function of the phenotypic variables (BMR, body composition indices, OGTT results).

Conceptual Diagrams & Workflows

Factors of Sensor Delay

Experiment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Metabolic and CGM Delay Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) | Captures continuous interstitial glucose readings for delay analysis. | Dexcom G7 (high accuracy, short warm-up) [24] or Dexcom G6 (extensively validated) [24]. |

| Reference Blood Glucose Analyzer | Provides the "gold standard" blood glucose measurement for calibrating and validating CGM delay. | Yellow Springs Instruments (YSI) Life Sciences analyzer. |

| Indirect Calorimeter | Precisely measures Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) and Resting Energy Expenditure (REE) for metabolic phenotyping. | Ventilated-hood systems (e.g., Cosmed Quark CPET). |

| Tri-axial Accelerometer | Objectively quantifies physical activity levels before and during metabolic testing to control for this variable. | Devices used for research-grade activity monitoring. |

| Body Composition Analyzer | Quantifies fat mass, lean body mass, and total body water, which are key covariates for metabolic rate. | Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA) scanner or Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA) scale. |

| Data Analysis Software | For statistical modeling, cross-correlation analysis, and development of machine learning algorithms for delay compensation. | Python/R, Dexcom Clarity Software [24], custom signal processing toolboxes. |

Algorithmic Solutions and Technical Approaches for Real-Time Sensor Delay Compensation

Troubleshooting Guide and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary sources of time delay in Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) signals, and how do they impact sensor performance? CGM signals are affected by a combination of physiological and technological time delays. The physiological delay, primarily due to the time required for glucose to diffuse from blood capillaries to the interstitial fluid (ISF) where most sensors are placed, is estimated to be 5-10 minutes on average [25]. The technological delay arises from sensor-specific factors, including the diffusion of glucose through the sensor's protective membranes, the speed of the electrochemical reaction, and the mathematical filtering applied to the raw signal to reduce noise. The total time delay can range from 5 to 40 minutes [25]. This delay can hamper the detection of rapid glucose changes, such as impending hypoglycemic events, and negatively impact the calculated Mean Absolute Relative Difference (MARD), a key metric for sensor accuracy [25].

Q2: How does a Kalman filter improve real-time CGM signal processing? The Kalman filter is a recursive algorithm ideally suited for real-time analysis of nonstationary time series data, such as CGM signals [26]. Its primary advantages include:

- Real-time Adaptation: It can adapt, in real-time, to abrupt changes in the signal baseline caused by external disturbances or physiological changes [26].

- Noise Reduction: It effectively reduces measurement noise without introducing significant lag, providing a smoother and more reliable glucose trend [26].

- Predictive Capability: By leveraging the dynamics of glucose diffusion between blood and tissue, the Kalman filter can estimate current blood glucose levels from interstitial fluid measurements, accounting for the inherent time delay [27]. One implementation uses the filter to improve the estimation accuracy of blood glucose levels from interstitial measurements [27].

Q3: What is time-dependent zero-signal correction, and what problem does it solve? Time-dependent zero-signal correction is a method to compensate for a sensor's baseline drift over time. The "zero-signal" refers to the sensor's output in the absence of the target analyte (e.g., glucose). This baseline is not static and can drift due to factors like sensor aging and material degradation [28] [29]. The method involves accurately determining this time-dependent zero-signal level and subtracting it from the continuous sensor signal [27]. This compensates for drift and interference, resulting in a more accurate representation of the actual glucose concentration in the body fluid [27].

Q4: My CGM data shows sudden, sharp drops. Could this be a compression artifact, and how can it be detected? Yes, sudden, sharp drops can be caused by compression artifacts, which occur when pressure is applied to the sensor site, temporarily disrupting the ISF glucose reading and potentially causing false hypoglycemia alarms. A patented method for real-time detection involves comparing clearance values between consecutive CGM readings to their normal distributions. If the clearance values fall outside these normal distributions, it indicates a compression artifact, allowing the system to flag the data point and prevent false alarms or inappropriate insulin shutoff [27].

Q5: What advanced machine learning approaches are being used for long-term drift compensation? Beyond traditional filters, advanced AI techniques are being explored to handle complex, nonlinear drift patterns. One novel framework combines an iterative random forest-based algorithm for real-time error correction with an Incremental Domain-Adversarial Network (IDAN) for long-term drift compensation [29]. The random forest algorithm leverages data from multiple sensor channels to identify and rectify abnormal responses, while the IDAN uses domain-adversarial learning to manage temporal variations in sensor data, significantly enhancing long-term data integrity [29].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High signal noise obscuring trends | Intrinsic electronic noise; environmental interference. | Apply a Kalman filter [26] or moving average filter. Balance filter length to avoid introducing excessive time delay [25]. |

| Systematic drift over sensor lifetime | Sensor aging (biofouling, material degradation) [25] [29]. | Implement time-dependent zero-signal correction [27] or employ machine learning models (e.g., Incremental Domain-Adversarial Network) trained for long-term drift compensation [29]. |

| Discrepancy between CGM and blood glucose during rapid changes | Physiological time lag (BG-to-ISF delay) and technological delay [25]. | Use a prediction algorithm or a Kalman filter to estimate blood glucose from ISF measurements, reducing the effective delay by several minutes [25] [27]. |

| Sudden, unrealistic signal dips | Compression artifact from physical pressure on the sensor [27]. | Implement a real-time detection algorithm that analyzes signal clearance values to identify and flag compression events [27]. |

| Declining sensor accuracy after initial calibration | Time-varying sensor sensitivity and calibration error [30]. | Utilize factory calibration parameters with machine learning or adopt dual-sensor calibration methods to estimate personalized, time-varying constants [27]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementing a Kalman Filter for CGM Signal Enhancement

Objective: To reduce noise and improve the real-time estimation of blood glucose from CGM (interstitial fluid) data.

Principles: The Kalman filter is a recursive estimator that optimally combines predictions from a process model with new measurements, each with known uncertainty. For CGM, the process model often describes glucose flux dynamics [27] [26].

Methodology:

- State Definition: Define the state vector. In its simplest form, this could be the true glucose level and its rate of change (e.g., ( xk = [Gk, Ḡk]^T ), where ( Gk ) is glucose concentration and ( Ḡ_k ) is its derivative at time ( k )).

- Process Model: Define a state transition model that predicts the next state. For example: ( x{k+1} = F \cdot xk + wk ), where ( F ) is the state transition matrix and ( wk ) is the process noise (assumed to be normally distributed).

- Measurement Model: Define how the sensor measurements relate to the state. Typically, ( zk = H \cdot xk + vk ), where ( zk ) is the CGM measurement, ( H ) is the observation matrix, and ( v_k ) is the measurement noise.

- Algorithm Execution: For each new CGM reading, execute the two-step Kalman filter algorithm:

- Predict Step: Project the previous state and error covariance forward.

- Update Step: Compute the Kalman gain, update the state estimate with the new measurement, and update the error covariance.

The filter's capability to adapt to nonstationary data makes it particularly valuable for handling the abrupt signal changes common in CGM data [26].

Protocol 2: Applying Time-Dependent Zero-Signal Correction

Objective: To compensate for the long-term baseline drift of a CGM sensor, thereby improving accuracy over its functional lifetime.

Principles: This method addresses the systematic deviation of a sensor's baseline (zero-signal) over time, which is a key component of sensor drift [27] [29].

Methodology:

- Baseline Characterization: During sensor development or a dedicated calibration period, characterize the zero-signal output of the sensor over time in a controlled, analyte-free environment.

- Model Fitting: Model the zero-signal drift as a function of time. This model could be a simple linear function, a polynomial, or a more complex machine-learned model, depending on the observed drift behavior.

- Real-time Correction: During sensor operation, continuously or periodically calculate the estimated zero-signal level based on the model and the sensor's elapsed operational time.

- Signal Adjustment: Subtract the estimated zero-signal value from the raw sensor signal to obtain the corrected glucose value:

Corrected Signal = Raw Sensor Signal - Time-Dependent Zero-Signal[27].

This approach directly counters one of the fundamental causes of inaccuracy in long-term sensor deployments [29].

Performance Data and Technical Specifications

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Signal Processing Algorithms

| Algorithm / Method | Key Performance Metric | Result / Value | Context / Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kalman Filter [27] | Improved delay estimation | Enables real-time BG estimation from ISF | Accounts for BG-to-ISF glucose diffusion dynamics. |

| Time-Dependent Zero-Signal Correction [27] | Compensates for sensor drift | Results in a more accurate glucose representation | Applied to raw CGM signal to counter drift and interference. |

| Prediction Algorithm [25] | Reduction in time delay | Average reduction of 4 minutes | Applied to CGM raw signals with an overall mean delay of 9.5 minutes. |

| Iterative Random Forest + IDAN [29] | Data integrity & drift compensation | Achieved robust accuracy with severe drift | Tested on a metal-oxide gas sensor array dataset over 36 months. |

| Random Forest Regressor [30] | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | 16.13 mg/dL | Model trained on a generated dataset of 500 sensor responses. |

| Support Vector Regressor [30] | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | 16.22 mg/dL | Model trained on a generated dataset of 500 sensor responses. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function in Research | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| CGM Sensor Simulator | Generates realistic glucose and sensor response data for algorithm development and testing. | Simglucose (FDA-approved UVa/Padova Simulator) [30]. |

| Long-term Drift Dataset | Provides benchmark data for developing and evaluating drift compensation algorithms. | Gas Sensor Array Drift (GSAD) Dataset [29] or a modern 62-sensor E-nose dataset [28]. |

| Metal-Oxide Sensor Array | Serves as a test platform for studying generalized drift phenomena in electrochemical sensors. | Commercial electronic nose (e.g., Smelldect) with multiple SnO2 sensors [28]. |

| Machine Learning Framework | Enables the implementation of complex correction models (Random Forest, SVMs, Neural Networks). | Python with scikit-learn, TensorFlow/PyTorch [29] [30]. |

| TinyML Platform | Allows the deployment of optimized ML models onto low-power, embedded micro-controllers for edge processing. | STM32 micro-controllers [30]. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Diagrams

Kalman Filter Process Flow

Zero-Signal Correction Logic

CGM Signal Delay Composition

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

This section addresses common technical and methodological questions researchers encounter when implementing SCINet architectures for Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) sensor delay compensation.

General SCINet Architecture

Q1: What is the core innovation of the SCINet architecture in processing glucose time-series data? SCINet (Simplified Complex Interval Neural Network) introduces a unique recursive down-sampling structure. It effectively captures multi-scale dynamic features in time-series data by recursively splitting the input sequence into sub-sequences at odd and even time positions. This process allows the network to extract features at different temporal resolutions, making it particularly suited for capturing the complex, multi-scale dynamics of glucose fluctuations [31].

Q2: How does the double-layer stacked SCINet model improve prediction performance? Stacking multiple SCINet layers creates a deeper hierarchical feature extraction process. The first layer captures fundamental temporal patterns, while the subsequent layer learns more complex, higher-order features from the first layer's output. This stacked architecture has demonstrated superior predictive performance across various prediction horizons (e.g., 15, 30, 60 minutes) compared to single-layer models and other time-series forecasting algorithms [31].

Sensor Delay & Lag Compensation

Q3: What is the physiological basis for CGM sensor delay, and how can SCINet models compensate for it? CGM sensors measure glucose concentration in the interstitial fluid, not the blood. This results in a physiological delay of approximately 10-20 minutes compared to fingerstick blood glucose measurements due to the time required for glucose to equilibrate across the capillary membrane [31] [32]. SCINet models address this through two primary strategies [31]:

- Extended Look-back Window: Using a 30-minute historical data window ensures the model input encompasses the period of physiological delay.

- Sensor Parameter Integration: Incorporating "sensor response time" (

sensor_k) as an input feature allows the model to learn and adjust for the specific delay characteristics of the sensor hardware.

Q4: My model's hypoglycemia alerts are delayed. How can I improve alert accuracy using the SCINet framework? Experimental results with the SCINet architecture show that explicit lag compensation, as described above, can improve hypoglycemia alert accuracy by up to 12% (e.g., from 78% to 90%). Ensure your model training pipeline includes sensor-specific delay parameters and that the prediction horizon accounts for both the physiological and algorithmic processing delays [31].

Data & Experimental Setup

Q5: What are the critical input features for training a robust SCINet glucose prediction model? Beyond the core CGM time-series, feature optimization is crucial. Key features include [31] [32]:

- Historical CGM values over a sufficiently long window (e.g., 30-60 minutes).

- Sensor-specific parameters, such as sensor response time (

sensor_k). - Physiological context from health records (e.g., HbA1c, weight, age) in a multimodal setup, which helps inform patient-specific glucose variations [32].

Q6: My model performs well on one sensor type but poorly on another. How can I improve generalizability? This is a common challenge due to inter-sensor variability. Employ a multimodal approach that incorporates sensor-type as a categorical feature or meta-parameter. Furthermore, training on datasets from multiple sensor types, like the Menarini and Abbott sensors used in related research, can enhance model robustness and generalizability across different hardware [32].

Quantitative Performance Data

The following tables summarize key performance metrics from recent studies utilizing advanced neural networks for glucose prediction, providing benchmarks for your SCINet experiments.

Table 1: Multimodal Deep Learning Model Performance

Performance of a CNN-BiLSTM with attention on different CGM sensors (Prediction Horizon: PH) [32].

| CGM Sensor Type | PH: 15 min MAPE (mg/dL) | PH: 30 min MAPE (mg/dL) | PH: 60 min MAPE (mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Menarini | 14 - 24 | 19 - 22 | 25 - 26 |

| Abbott | 6 - 11 | 9 - 14 | 12 - 18 |

Table 2: Comparative Model Performance on Ohio T1DM Dataset

Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of various models for 30-minute and 60-minute prediction horizons [31].

| Model Architecture | 30-min RMSE (mg/dL) | 60-min RMSE (mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|

| Support Vector Regression (SVR) | ~20.38 (with feature engineering) | - |

| Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) | 20.7 ± 3.2 | 33.6 ± 3.2 |

| Artificial Neural Network (ANN) | 19.33 | 31.72 |

| SCINet (Proposed) | Outperforms above models | Outperforms above models |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Core Protocol: Implementing a SCINet for Glucose Prediction

This protocol outlines the key steps for building and evaluating a SCINet model, incorporating lag compensation.

1. Data Preprocessing & Lag Compensation Setup:

- Data Sourcing: Utilize CGM data from real-patient records. Example sources include hospital inpatient data or publicly available datasets like Ohio T1DM [31].

- Data Cleansing: Handle signal loss and sensor failure artifacts using interpolation or data rejection strategies [32].

- Lag Compensation: Integrate the sensor response time parameter (

sensor_k) as a model feature. Structure the input data with a look-back window that covers the physiological delay period (e.g., 30 minutes) [31].

2. Model Architecture Configuration:

- SCI-Block: Implement the basic building block of SCINet, which decomposes input features into two sub-features through splitting and interactive learning operations [31].

- Stacking: Construct a double-layer SCINet stack to enable multi-scale feature learning. The first layer processes the original sequence, while the second layer processes the transformed features from the first, capturing hierarchical temporal patterns [31].

- Output: Configure the final layers for regression to predict future glucose values (e.g., 15, 30, 60 minutes ahead).

3. Training & Validation:

- Training Dataset: Train the model using multiple continuous glucose monitoring datasets.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Conduct multiple experiments to optimize hyperparameters (e.g., learning rate, number of filters, depth of recursion).

- Performance Validation: Validate predictive performance on a held-out test dataset. Use metrics like RMSE and MAPE, and compare against baseline time-series prediction algorithms [31].

The workflow for this protocol, including the crucial step of lag compensation, is visualized below.

The Lag Compensation Mechanism

The following diagram details the internal process of the Lag Compensation Module, a critical component for accurate prediction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential computational and data components for conducting research in this field.

| Item/Resource | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|

| CGM Datasets (e.g., Ohio T1DM, Yixing People's Hospital data) | Provides the foundational time-series data for model training and validation. Essential for benchmarking algorithm performance [31]. |

| SCINet Architecture | The core neural network model for multi-scale temporal feature extraction. Replaces traditional RNNs/CNNs for potentially superior performance on glucose prediction tasks [31]. |

| Sensor Response Parameter (sensor_k) | A critical input feature that models the relationship between signal delay and specific sensor hardware parameters, directly enabling lag compensation [31]. |

| Multimodal Health Data (e.g., HbA1c, weight, age) | Provides physiological context. When fused with CGM data in a model, it helps account for inter-individual variability and improves personalization [32]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Necessary for efficient training of deep learning models like stacked SCINet, which require significant computational resources for hyperparameter tuning and multiple experiments [31]. |

What are Hybrid Monitoring Systems in Glucose Research? Hybrid monitoring systems combine invasive (or minimally invasive) and non-invasive sensors to continuously measure blood glucose levels. The primary goal is to leverage the proven accuracy of invasive methods, such as Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGMs), to validate and enhance the performance of non-invasive sensors, which are often affected by physiological and technical challenges [2] [33]. A central research focus is sensor delay compensation, which addresses the time lag between glucose levels in the blood plasma and the readings from interstitial fluid or non-invasive sensors [2].

Why is Data Correlation Crucial? Correlating data from these different sensor types is essential for developing accurate and clinically reliable non-invasive monitoring devices. This process helps overcome issues like:

- Physiological Delays: The natural time lag (estimated at 6-10 minutes) for glucose to diffuse from blood vessels into the interstitial fluid where some sensors operate [2].

- Technical Delays: Latency introduced by the sensor's own technology and signal processing algorithms [2].

- Signal Interference: Non-invasive optical signals can be affected by skin color, ambient light, finger pressure, and other biological components, making calibration with a trusted reference vital [33].

Troubleshooting Common Integration Issues

FAQ 1: How do I resolve a consistent time lag between my invasive and non-invasive sensor readings?

- Problem: A persistent delay is observed between the glucose value from the reference CGM and the non-invasive sensor.

- Solution: This is often an expected physiological and technical delay. Implement and compare these two data alignment methods:

- MARD Minimization: Shift the non-invasive sensor's glucose values in time (e.g., by 5, 10, or 15 minutes) and calculate the Mean Absolute Relative Difference (MARD) at each shift point. The time shift that yields the minimum MARD is the optimal delay for your system [2].

- Minimum Deviation Match: For each reference plasma glucose measurement, find the non-invasive sensor value within a subsequent time window (e.g., 0-15 minutes) that has the smallest absolute difference. This method can account for variable delays, especially during rapid glucose changes like an Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) [2].

FAQ 2: What should I check if the correlation between sensors is weak or inconsistent?

- Problem: The data from the invasive and non-invasive sensors show poor correlation, making reliable calibration impossible.

- Solution: Follow this troubleshooting checklist:

- Verify Sensor Placement and Operation: Ensure the non-invasive sensor (e.g., an optical unit) is correctly positioned and making consistent contact. Loose connections or movement artifacts can corrupt data [33].

- Check for Environmental Interference: Ambient light or significant temperature fluctuations can interfere with optical sensors. Conduct experiments in a controlled environment and use sensor designs that shield against such noise [33].

- Inspect Data Quality: Examine the raw signal from the non-invasive sensor for anomalies or dropouts. Algorithms may struggle with poor-quality input data.

- Validate Reference Method: Ensure the invasive reference sensor (CGM) is properly calibrated and functioning correctly. A faulty reference will lead to incorrect correlation.

FAQ 3: How can I improve the accuracy of my non-invasive glucose predictions?

- Problem: Even after correlation, the non-invasive sensor's glucose predictions have unacceptably high error.

- Solution: Move beyond simple linear regression models. Employ advanced machine learning techniques:

- Use Classification over Regression: Instead of predicting a continuous glucose value, train a model to classify readings into discrete glucose ranges (e.g., bins of 10 mg/dL). This can significantly improve the accuracy of identifying clinically critical hypoglycemic or hyperglycemic states [34].

- Leverage Multiple Wavelengths: If using an optical sensor, utilize multiple light wavelengths (e.g., 485, 645, 860, and 940 nm) instead of a single one. This multi-wavelength approach helps compensate for errors caused by inter-individual differences in tissue and blood components [34].

- Implement Robust Algorithms: Studies have shown that Support Vector Machines (SVM) and other classification models can achieve high accuracy (F1-scores of 99%) and place over 99% of readings in clinically acceptable zones of a Clarke Error Grid analysis [34].

Experimental Protocols for Data Correlation

The following workflow details a standardized method for correlating data from invasive and non-invasive sensors, crucial for delay compensation research.

Detailed Methodology:

Participant Preparation & Sensor Deployment:

- Recruit participants according to study protocol (e.g., healthy adults or diabetic patients) with informed consent [2].

- Place the reference sensor (e.g., a CGM like the SiJoy GS1 on the posterior upper arm) at least 48 hours before intensive testing to allow for stabilization [2].

- Deploy the non-invasive sensor (e.g., a custom NIR optical sensor with wavelengths such as 940 nm on the finger or wrist) [34] [33].

Provocative Testing & Data Collection:

- After an overnight fast, perform an Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) by administering 75g of glucose solution [2].

- Collect venous Plasma Glucose (PG) samples at key time points: 0 (fasting), 30, 60, 120, and 180 minutes. This provides the gold-standard reference [2].

- Simultaneously, record glucose readings from both the CGM and the non-invasive sensor at high frequency (e.g., every 5 minutes). Also, record any potential confounding factors like skin temperature or patient activity [2] [33].

Data Pre-processing & Synchronization:

- Synchronize all datasets (PG, CGM, non-invasive) using precise timestamps.

- Clean the data by handling outliers and correcting for any baseline drift in sensor signals.

Time Lag Analysis and Data Alignment:

- Use one of the two methods described in the FAQs to determine the optimal time shift between the PG reference and the sensor signals.

- Align the datasets based on the calculated delay.

Model Training and Validation:

- Use the aligned data to train a machine learning model. The features could be raw optical intensities from multiple wavelengths, and the target is the reference PG value (for regression) or its class (for classification) [34] [33].

- Validate the model's performance on a separate, unseen dataset.

- Use robust metrics and tools like the Clarke Error Grid (CEG) to analyze clinical accuracy, Bland-Altman plots to assess agreement, and Mean Absolute Relative Difference (MARD) to quantify overall error [2] [33].

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies, providing benchmarks for your hybrid system's evaluation.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Glucose Monitoring Systems from Recent Research

| System / Study Focus | Key Performance Metrics | Data Analysis Method | Reported Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-invasive Optical Sensor [34] | Prediction Accuracy, F1-Score, Clarke Error Grid | Support Vector Machine (SVM) Classification | 99% F1-Score; 99.75% of readings in clinically acceptable zones (CEG) |

| SiJoy GS1 CGM Evaluation [2] | MARD, Clarke Error Grid | MARD Minimization & Minimum Deviation Match | Overall MARD of 8.01%; 89.22% in CEG Zone A, 100% in Zone A+B |

| niGLUC-2.0v Sensor Prototype [33] | Accuracy, Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Clarke Error Grid | Ridge Regression (RR) | Wrist prototype Accuracy: 99.96%, MAE: 0.06; 100% in CEG Zone A |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Hybrid Glucose Sensor Research

| Item | Specification / Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Reference CGM | SiJoy GS1, Dexcom G6 | Provides calibrated, continuous interstitial glucose readings to serve as a benchmark for correlation [2]. |

| Non-Invasive Sensor Prototype | Custom NIR sensor (e.g., 940 nm LED, 900-1700 nm detector) | Measures optical properties (absorption/scattering) correlated with glucose levels without breaking the skin [34] [33]. |

| Clinical Glucose Analyzer | AU5800 (Beckman Coulter) | Provides gold-standard Plasma Glucose (PG) measurements from venous blood draws for ultimate validation [2]. |

| Data Acquisition System | Custom PCB with microcontroll-er, Triad AS7265x Spectrometer | Captures raw analog signals from sensors and converts them to digital data for analysis [34]. |

| Standardized Glucose Challenge | 75g Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) | Induces rapid and predictable changes in blood glucose, essential for studying dynamic response and time lags [2]. |

System Calibration and Validation Logic

Achieving a clinically acceptable system requires a rigorous, iterative process of calibration and validation, as outlined below.

FAQs: Understanding Compression in Monitoring Systems

Q1: What is a compression artifact and how does it affect data? A compression artifact is a noticeable distortion of media (including images, audio, and video) caused by the application of lossy data compression [35]. This occurs when data is discarded to reduce file size for storage or transmission, potentially introducing errors. In the context of Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM), failures such as compression artifacts can impact both real-time and retrospective data analysis [36]. These artifacts can obscure true physiological signals, such as glucose fluctuations, leading to inaccurate clinical interpretations.

Q2: Why is real-time artifact detection and compensation crucial for CGM systems? CGM systems measure glucose in the interstitial fluid, not in blood. Rapid changes in blood glucose are not accompanied by similar immediate changes in the interstitial fluid but follow with a physiological time delay [37]. This delay, with a mean of approximately 9.5 minutes [37], hampers the detection of fast glucose changes, such as the onset of hypoglycemia. When compression artifacts affect the data stream, they compound this inherent delay, further degrading data quality and reliability for real-time therapy decisions like insulin dosing.

Q3: What are the common types of artifacts in data streams? Artifacts manifest differently depending on the data type:

- In Video/Imaging: Common artifacts include "blockiness" (also called blocking or quilting), "ringing" around edges, and "mosquito noise" (a shimmering blur of dots around edges) [35]. These are prevalent in formats like MPEG and JPEG.

- In Sensor Data (e.g., CGM): Artifacts can appear as physiologically implausible signal drop-outs, rapid fluctuations, or "spikes" [36]. These are distinct from the sensor's inherent time delay and represent data integrity failures.

Q4: How can researchers detect compression artifacts in CGM data? A data-driven, supervised approach can be effective. One method involves generating an in-silico dataset (e.g., using the T1D UVa/Padova simulator) and adding compression artifacts at known positions to create a labeled dataset. The detection problem can then be addressed using supervised algorithms like Random Forest, which has shown satisfactory performance in detecting these faults on simulated data [36].