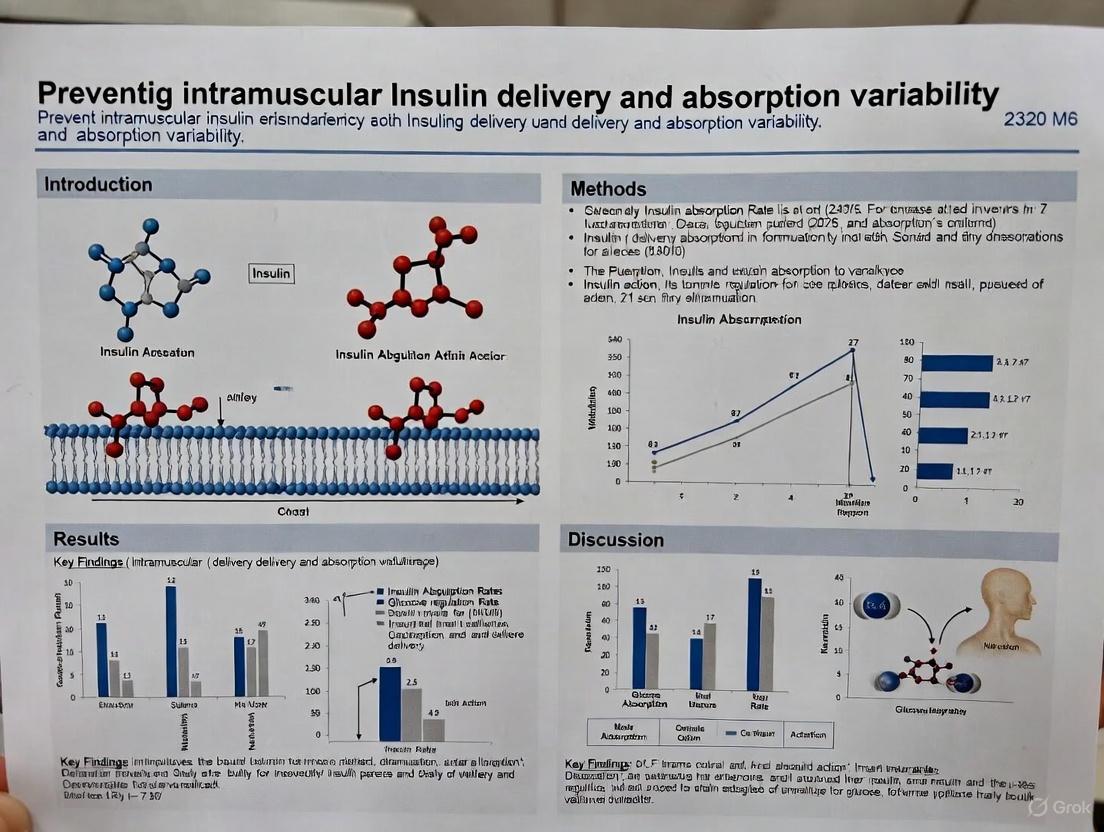

Optimizing Subcutaneous Insulin Delivery: Strategies to Prevent Intramuscular Injection and Reduce Absorption Variability in Diabetes Therapy

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the factors contributing to unpredictable insulin absorption, with a specific focus on the risks and consequences of unintentional intramuscular (IM) delivery.

Optimizing Subcutaneous Insulin Delivery: Strategies to Prevent Intramuscular Injection and Reduce Absorption Variability in Diabetes Therapy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the factors contributing to unpredictable insulin absorption, with a specific focus on the risks and consequences of unintentional intramuscular (IM) delivery. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational physiology, current injection methodologies, and troubleshooting strategies for lipohypertrophy. The content further explores validation techniques using continuous glucose monitoring and comparative analyses of insulin regimens, while also surveying the horizon of emerging technologies, including automated insulin delivery systems and smart injection devices, that promise to mitigate variability and enhance glycemic control.

The Science of Subcutaneous Absorption: Physiology and Pathophysiology of Insulin Variability

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is understanding skin and subcutaneous tissue thickness critical for intramuscular insulin delivery research?

Accurate understanding of these layers is essential to prevent inadvertent intramuscular (IM) injection, which can lead to unpredictable insulin absorption and affect glycemic control. Research shows that skin thickness (ST) is relatively consistent across populations and injection sites, while subcutaneous adipose layer thickness (SCT) varies significantly with body mass index (BMI), gender, and race. [1] Using a needle longer than the SCT at a given site, especially in lean individuals or certain body areas like the limbs, risks depositing insulin into muscle tissue. This can accelerate absorption into the bloodstream, potentially causing rapid glucose lowering and increasing hypoglycemia risk, thereby introducing significant variability in pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies. [1]

Q2: What are the key anatomical landmarks and risks associated with different injection sites?

The selection of an injection site must consider the underlying anatomy to avoid neurovascular injury. [2] The following table summarizes common sites:

| Injection Site | Anatomical Landmark Description | Key Neurovascular Structures to Avoid |

|---|---|---|

| Ventrogluteal | Triangle formed by placing the heel of the hand on the greater trochanter, index finger on the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), and middle finger along the iliac crest. Inject in the center of the triangle. [2] [3] | Superior and inferior gluteal arteries; Gluteal nerves. Considered the safest gluteal site with the thickest muscle and absence of major nerves. [2] [3] |

| Deltoid | Approximately 2.5 to 5 cm below the acromion process, in the middle of the muscle belly. [2] [3] | Axillary and radial nerves. The safe zone is approximately 7–13 cm below the mid-acromion, midway between the acromion and deltoid tuberosity. [2] |

| Vastus Lateralis | Middle third of the line joining the greater trochanter of the femur and the lateral femoral condyle of the knee. [2] | Femoral nerve and blood vessels. The middle of the muscle is considered safe. [2] |

| Dorsogluteal | Upper outer quadrant of the buttock. [2] | Sciatic nerve. This site is not routinely recommended due to its proximity to the sciatic nerve and major blood vessels, and inconsistent depth of adipose tissue. [2] [3] |

Q3: What experimental methodology is used to precisely measure skin and subcutaneous tissue thickness?

High-resolution ultrasonography is the standard, non-invasive method for obtaining precise measurements of skin thickness (ST) and subcutaneous adipose layer thickness (SCT) in vivo. [1]

Experimental Protocol:

- Subject Preparation: Recruit a diverse cohort of adults (e.g., by BMI, gender, race). Stabilize subjects in a relaxed, supine or sitting position for at least 5 minutes prior to measurement to ensure consistent muscle tone and blood flow.

- Site Selection and Marking: Clearly mark the four standard injection sites (abdomen, arm, thigh, buttock) using anatomical landmarks. Ensure consistency in the exact location measured across all subjects.

- Ultrasound Imaging: Use a high-frequency linear array ultrasound transducer (e.g., ≥10 MHz). Apply a generous amount of water-soluble transmission gel to the mark on the skin to ensure acoustic coupling. Place the transducer perpendicular to the skin surface without compressing the underlying tissues, as compression can artificially reduce SCT measurements.

- Image Capture and Measurement: Capture a static image. On the ultrasound image:

- Skin Thickness (ST): Measure the distance from the skin surface (entry echo) to the entrance of the dermis into the subcutaneous tissue.

- Subcutaneous Tissue Thickness (SCT): Measure the distance from the dermo-hypodermal junction to the surface of the muscle fascia. [1]

- Data Analysis: Perform multiple measurements per site per subject to ensure reliability. Analyze data using multivariate analyses to determine the statistical significance of factors like body site, gender, and BMI.

Q4: My research involves repeated injections in an animal model. What complications should I monitor for?

Common complications from IM injections include pain, bleeding, and inflammation. More serious complications to monitor for include:

- Nerve Injury: Resulting from direct needle trauma or compression from a hematoma. This can cause pain, paresthesia, or paralysis (e.g., foot drop from sciatic nerve injury). [2]

- Abscess Formation: Caused by bacterial introduction due to inadequate aseptic technique, or as a sterile aseptic abscess from insoluble or irritating drugs. [4] [2]

- Tissue Necrosis: Occurs from injecting substances contraindicated for IM administration, such as calcium chloride. [4]

- Intramuscular Hematoma: A particular risk in subjects with thrombocytopenia or coagulation defects. [2] [3]

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution / Preventive Action |

|---|---|---|

| High variability in insulin absorption data | Inadvertent intramuscular injection due to inappropriate needle length for the subject's SCT. | Use ultrasound to measure SCT at the study site. Select a needle length that ensures subcutaneous deposition without risk of IM injection. For most adults, a 4-5 mm needle inserted at 90° minimizes IM risk. [1] |

| Subject reports severe pain or neurological symptoms post-injection | Needle contact with or injury to a peripheral nerve. | Immediately suspend dosing. Perform a neurological assessment. Confirm injection technique and site landmarks. For subsequent injections, switch to a safer site (e.g., ventrogluteal over dorsogluteal) and ensure correct landmark identification. [2] |

| Induration, swelling, or redness at injection site | Sterile abscess from irritating drug formulation or infectious abscess from breached asepsis. | Ensure strict aseptic technique. For irritating drugs, use the Z-track technique to seal the medication in the muscle. Rotate injection sites frequently to prevent lipohypertrophy and allow tissue recovery. [4] [2] [3] |

| Unexpectedly rapid hypoglycemia following insulin administration | Insulin deposited directly into muscle tissue, leading to accelerated absorption. | Review and confirm the needle length and injection technique are appropriate for the subject's SCT. Aspirate before injection (if using the dorsogluteal site) to check for blood, though note this practice is debated for other sites. [1] [3] |

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from Gibney et al. (2010) on skin and subcutaneous tissue thickness in adults with diabetes. [1]

Table 1: Mean Skin Thickness (ST) and Subcutaneous Tissue Thickness (SCT) by Injection Site

| Injection Site | Mean Skin Thickness (mm) (± 95% CI) | Mean Subcutaneous Tissue Thickness (mm) (± 95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Abdomen | 2.2 (2.1, 2.2) | 13.9 (13.2, 17.7) |

| Arm | 2.2 (2.2, 2.3) | 10.8 (10.2, 11.3) |

| Thigh | 1.9 (1.8, 1.9) | 10.4 (9.8, 10.9) |

| Buttocks | 2.4 (2.4, 2.5) | 15.4 (14.7, 16.2) |

Table 2: Impact of Subject Factors on Tissue Thickness

| Factor | Impact on Skin Thickness (ST) | Impact on Subcutaneous Tissue (SCT) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (Female vs. Male) | Statistically significant, but small effect. | Females had 5.1 mm greater mean SCT. [1] |

| BMI (Difference of 10 kg/m²) | Accounts for ~0.2 mm variation. [1] | Accounts for ~4.0 mm variation. [1] |

| Race | Statistically significant, but small effect. | Significant factor, with wider variation. [1] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| High-Frequency Linear Ultrasound | Non-invasive measurement of skin and subcutaneous tissue thickness at designated injection sites with high precision. [1] |

| Anatomical Marking Pen | Precisely marks injection sites based on standardized anatomical landmarks to ensure consistency across measurements and injections. |

| Water-Soluble Ultrasound Gel | Provides acoustic coupling between the ultrasound transducer and the skin, enabling clear image acquisition without compressing the tissue. |

| Fixed-Capacity Insulin Syringes (Various Needle Lengths) | Allows for systematic investigation of how needle length (e.g., 4mm, 5mm, 8mm, 12.7mm) affects injection depth and insulin deposition. |

| Bioassay/Analytical Platform (e.g., ELISA, HPLC) | Measures serum insulin levels and/or glucose kinetics to quantify the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic variability resulting from different injection depths. |

Anatomical and Experimental Visualization

Injection Site Anatomy and Needle Depth

Experimental Workflow for Tissue Measurement

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Researchers

FAQ 1: What are the primary physiological structures that form a barrier to insulin delivery in the subcutaneous tissue? The subcutaneous tissue is composed of adipose tissue separated by connective tissue septae. The extracellular matrix (ECM) within this connective tissue is the main physiological barrier. The ECM consists of proteins like collagen and elastin, as well as glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). Insulin must navigate this gel-like matrix before reaching the systemic circulation. Furthermore, insulin can bind to ECM proteins like collagen, which may act as temporary tissue reservoirs [5].

FAQ 2: How does the molecular state of insulin influence its absorption pathway? Upon injection, soluble insulin exists in an equilibrium of monomers, dimers, and hexamers. Monomers (6 kDa) and dimers (12 kDa) are small enough to be absorbed directly into the blood capillaries. Larger hexamers (36 kDa) are generally not absorbed into capillaries but can be taken up by the lymphatic system due to its more permeable structure. The absorption process involves the dissociation of injected hexamers into dimers and monomers at the injection site [5].

FAQ 3: How do injection parameters affect the formation and dispersion of a subcutaneous insulin depot? Recent high-resolution imaging studies show that injection parameters significantly influence depot morphology. Higher injection volumes lead to larger, less spherical depots with greater surface area. The formation of tissue "cracks" during injection can direct plume spread along specific pathways, influencing initial drug distribution. Faster initial flow rates, common in autoinjectors, can increase initial depot pressure but do not necessarily change the final shape [6].

FAQ 4: What is the role of the lymphatic system in insulin absorption? The lymphatic system plays a complementary role, particularly for larger insulin molecules or complexes. Lymphatic capillaries, located in a plexus between the dermis and subcutis, have endothelial cells that lack tight junctions, allowing the uptake of larger molecules. The composition of interstitial fluid is similar to plasma but with a much lower protein content, and fluid not recovered by blood venules is absorbed by the lymphatic system [5] [7].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: High Variability in Absorption Pharmacokinetics

- Potential Cause: Injection technique and site selection. Physiological factors such as local blood flow, skin temperature, and exercise can increase subcutaneous blood flow, thereby accelerating absorption.

- Solution: Standardize injection protocols across study subjects. Utilize imaging techniques like synchrotron CT or radiography to visualize and control for depot formation. Ensure consistent injection depth to avoid accidental intramuscular delivery, which has a faster absorption profile [5] [6].

Challenge 2: Unexpectedly Slow or Rapid Insulin Absorption Profile

- Potential Cause: Formulation-excipient interactions in the subcutaneous space. Excipients like phenol and meta-cresol stabilize insulin hexamers in the vial. Upon SC injection, their dispersion away from the depot shifts the equilibrium towards absorbable dimers and monomers. Issues with this dissociation can alter the absorption rate.

- Solution: Characterize the oligomer dissociation kinetics of your insulin formulation under simulated subcutaneous conditions. Consider the isoelectric point of the insulin preparation and its potential binding to ECM components [5].

Quantitative Data on Factors Influencing Insulin Absorption

Table 1: Molecular Oligomers of Insulin and Their Absorption Pathways

| Oligomer State | Molecular Weight | Primary Absorption Pathway | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monomer | 6 kDa | Blood Capillaries | Readily absorbed into circulation [5] |

| Dimer | 12 kDa | Blood Capillaries | Readily absorbed into circulation [5] |

| Hexamer | 36 kDa | Primarily Lymphatic System | Must dissociate into dimers/monomers for capillary uptake [5] |

Table 2: Impact of Autoinjector Delivery Volume on Depot Morphology (Ex-Vivo Data)

| Injection Volume | Depot Volume (mL) | Aspect Ratio | Sphericity | Surface Area (mm²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 mL | 0.48 | 2.10 | 0.68 | 340 |

| 1.0 mL | 0.95 | 2.35 | 0.62 | 520 |

| 2.0 mL | 1.89 | 2.92 | 0.49 | 810 |

Data adapted from synchrotron CT analysis of injections into excised pork belly tissue [6].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Synchrotron Imaging of SC Depot Formation

This protocol details the methodology for visualizing real-time subcutaneous depot formation and diffusion, as utilized in recent studies [6].

1. Objective: To characterize the impact of injection parameters (e.g., volume, flow rate) on the initial formation, morphology, and diffusion of a subcutaneous drug depot.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Test Formulation: Iodine-based contrast solution (e.g., 30% w.t.) to simulate drug fluid with radiopaque properties.

- Biological Substrate: Excised pork belly tissue, used as a model for human subcutaneous tissue due to its structural similarity.

- Delivery Device: Autoinjectors with varying designed volumes (e.g., 0.5 mL, 1.0 mL, 2.0 mL).

- Imaging Equipment: Synchrotron facility for high-speed, high-resolution imaging.

- Synchrotron Radiography: For real-time 2D visualization of plume growth during injection (temporal resolution: ~1.02 seconds per frame).

- Synchrotron Computed Tomography (CT): For post-injection 3D reconstruction of final depot morphology.

3. Methodology: 1. Sample Preparation: Equilibrate autoinjectors and biological tissue to a standard room temperature (e.g., 20-25°C) to minimize temperature-induced variability. 2. Image Acquisition: - Radiography Setup: Position the autoinjector perpendicular to the tissue surface and the synchrotron X-ray beam. - Injection & Recording: Initiate the autoinjector and simultaneously begin high-speed radiography to capture the dynamic process of fluid ejection, tissue displacement, and plume formation. - Post-injection CT Scan: After needle retraction, perform a CT scan of the tissue sample to obtain a 3D model of the deposited depot. 3. Data Analysis: - Plume Growth Kinematics: From radiography sequences, analyze the rate and direction of plume expansion, noting the formation of tissue cracks. - Depot Morphometry: From CT data, calculate quantitative metrics for the final depot, including volume, surface area, aspect ratio, and sphericity. - Diffusion Analysis: Measure the mean gray value intensity in regions around the depot periphery over time to quantify the diffusion of the contrast solution into the surrounding tissue.

Pathway and Experimental Visualization

Insulin Absorption Pathway

SC Depot Imaging Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for SC Absorption and Depot Formation Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Iodine Contrast Solution | Simulates the drug formulation, providing radiopacity for high-resolution X-ray imaging with synchrotron CT or radiography [6]. |

| Excised Pork Belly Tissue | Serves as an ex-vivo biological substrate that models the structural properties of human subcutaneous tissue for injection studies [6]. |

| Autoinjector Devices | Provides a standardized, clinically relevant method for administering subcutaneous injections with controlled parameters [6]. |

| Synchrotron Imaging Facility | Enables real-time, high-speed radiography and high-resolution CT imaging to visualize dynamic fluid-structure interactions during and after injection [6]. |

| Recombinant Human Insulin & Analogues | The active pharmaceutical ingredient for pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies. Includes rapid-, short-, intermediate-, and long-acting types [5]. |

| Stabilizing Excipients (Phenol, meta-cresol, Zinc) | Used in formulations to control insulin oligomerization (shifting equilibrium toward hexamers) and study their dissociation kinetics in the subcutaneous space [5]. |

FAQs: Intramuscular Delivery and Pharmacokinetics

Q1: What are the primary pharmacokinetic consequences of accidental intramuscular (IM) insulin delivery? Accidental IM delivery of insulin significantly alters its pharmacokinetic profile. Uptake from muscle tissue is markedly faster and more variable than from subcutaneous (SC) fat, leading to unpredictable blood glucose levels. This erratic absorption increases the risk of both hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia, compromising treatment safety and efficacy [8] [9]. The variability is further amplified if the muscle is exercised, accelerating uptake even more [8].

Q2: How can researchers ensure subcutaneous deposition in animal or human studies? The most effective strategy is to use the shortest needle possible. For most subjects, including adults and children, 4-mm needles are sufficient to reliably reach the SC tissue while minimizing the risk of IM injection. In very lean subjects, a skinfold lift is recommended, even with short needles. The use of longer needles (≥8 mm) substantially increases the risk of IM deposition and should be avoided [8] [10].

Q3: What is lipohypertrophy (LH) and how does it impact drug absorption? LH is a localized thickening of fatty tissue and a common complication of repeated SC injections, with a prevalence of over 50% in some studies. It is caused by improper injection site rotation and needle reuse. Injecting into LH lesions reduces and delays insulin absorption, increases pharmacokinetic variability, and leads to suboptimal glucose control [8] [9].

Q4: What are the best practices for injection site rotation to prevent tissue complications? A structured rotation schedule is crucial. The recommended practice is to use the same general area (e.g., abdomen) at the same time of day but rotate the exact injection spot within that site. The area should be divided into quadrants or halves, with daily injections administered at least 1-2 cm (about one finger's width) apart. This prevents repeated trauma to the same spot of tissue, reducing the risk of LH [10].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Injection Technique Errors

| Error | Consequence | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Using overly long needles [8] [10] | High risk of intramuscular injection, leading to faster, erratic drug uptake. | Switch to 4-mm pen needles for most subjects. Use 5-mm or 6-mm needles only with a skinfold or 45° angle if 4-mm is unavailable [8]. |

| Injecting into Lipohypertrophy (LH) [8] [9] | Unpredictable and reduced drug absorption, leading to poor glycemic control and unexplained glucose fluctuations. | Implement a structured site rotation plan. Visually inspect and palpate sites regularly. Avoid injecting into hardened or lumpy areas [10]. |

| Applying excessive injection force [10] | Increases the risk of depositing the drug intramuscularly. | Train on gentle needle insertion. If a dent is visible on the skin from force, pressure is too high. Consider contoured-needle designs [10]. |

| Reusing pen needles [8] [10] | Increases risk of LH, infection, pain, and bleeding. Compromises sterility and injection accuracy. | Counsel on "one needle, one injection" policy. Ensure an adequate supply of needles is provided to the patient/study subject [10]. |

| Incorrect skinfold technique with short needles [10] | Unnecessary complexity; for most adults, a skinfold is not required with 4-mm or 5-mm needles. | For 4-mm needles, a perpendicular (90°) injection without a skinfold is appropriate for most adults. Reserve skinfolds for very lean subjects and children [8]. |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Delivery Kinetics

Protocol 1: Ultrasonography for Tissue Depth Measurement

Objective: To determine SC adipose tissue thickness at various injection sites to inform appropriate needle length selection.

- Subject Positioning: Position the subject supine for abdominal and thigh sites, or in a lateral decubitus position for ventrogluteal sites.

- Site Marking: Mark standard injection sites (abdomen, thigh, arm, buttocks) for consistent measurement.

- Imaging: Use a high-frequency linear array ultrasound probe. Apply a generous amount of water-soluble gel to the transducer head.

- Measurement: Place the transducer perpendicular to the skin surface without compressing the tissue. Capture images and measure the distance from the skin surface to the muscle fascia. Take multiple measurements per site.

- Data Analysis: Correlate SC thickness with subject demographics (BMI, sex, age) to identify risk factors for IM injection [8].

Protocol 2: Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) Profiling of SC vs. IM Delivery

Objective: To quantitatively compare the absorption and action profiles of a drug delivered via SC and IM routes.

- Study Design: A controlled, crossover study is recommended.

- Dosing: Administer a standardized dose of the drug (e.g., insulin) via both SC and IM routes in the same subject, with an adequate washout period between interventions.

- Blood Sampling: Collect frequent serial blood samples over a period covering the drug's expected duration of action.

- SC Analysis: Measure serum drug concentrations (e.g., insulin levels) to generate PK parameters: Time to maximum concentration (T~max~), Maximum concentration (C~max~), and Area Under the Curve (AUC).

- PD Analysis: For insulin, measure blood glucose levels at the same time points to determine the glucose-lowering effect [8].

- Data Interpretation: Compare PK/PD parameters between SC and IM routes. IM injection is expected to show a significantly shorter T~max~, higher C~max~, and greater variability in both PK and PD measures, especially if the muscle is active [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| 4-mm Pen Needles | The recommended needle length for ensuring consistent subcutaneous deposition and minimizing the risk of intramuscular injection in most subjects, from children to obese adults [8] [9]. |

| High-Frequency Linear Ultrasound | Used to precisely measure skin and subcutaneous tissue thickness at potential injection sites, providing an evidence base for selecting appropriate needle lengths [8] [9]. |

| Contoured-Hub Needles | Pen needles with a redesigned hub that distributes insertion force over a larger area, reducing variability in penetration depth caused by differing application pressures [9]. |

| Vials and Syringes (for control) | Traditional delivery method used as a control in experiments comparing the pharmacokinetic profiles of different delivery systems (e.g., vs. pen devices) [9]. |

Diagrams of Pathways and Workflows

DOT Script for Drug Delivery Pathway

DOT Script for Experimental PK Workflow

Data presented as mean thickness in millimeters (mm) measured via ultrasonography.

| Body Site | BMI Category (kg/m²) | Skin Thickness (mm) | SC Tissue Thickness (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arm | < 23 | : 1.7 | : 3.6 |

| : 1.5 | : 6.5 | ||

| 23-25 | : 1.9 | : 7.6 | |

| : 1.8 | : 11.1 | ||

| > 25 | : 2.1 | : 12.5 | |

| : 2.1 | : 15.3 | ||

| Thigh | < 23 | : 1.7 | : 4.4 |

| : 1.5 | : 8.5 | ||

| 23-25 | : 1.9 | : 8.2 | |

| : 1.8 | : 13.3 | ||

| > 25 | : 2.1 | : 14.3 | |

| : 2.1 | : 19.2 | ||

| Abdomen | < 23 | : 1.6 | : 5.8 |

| : 1.6 | : 8.1 | ||

| 23-25 | : 1.8 | : 10.3 | |

| : 1.7 | : 13.9 | ||

| > 25 | : 1.9 | : 18.4 | |

| : 1.9 | : 19.1 |

Model-adjusted mean thickness (mm) in a diabetic population. Dermis thickness includes the epidermis.

| Cohort | Group | Abdominal Dermis (mm) | Abdominal Subcutis (mm) | Thigh Dermis (mm) | Thigh Subcutis (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children (Pre-pubertal) | Boys | 1.45 | 7.10 | 1.30 | 6.10 |

| Girls | 1.43 | 7.00 | 1.28 | 6.00 | |

| Children (Pubertal) | Boys | 1.89 | 9.25 | 1.60 | 7.78 |

| Girls | 1.83 | 16.70 | 1.57 | 16.70 | |

| Adults | Men | 2.10 | 17.90 | 1.89 | 9.80 |

| Women | 1.99 | 21.30 | 1.65 | 17.70 |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Objective: To obtain accurate and reproducible measurements of skin and subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) thickness at key anatomical sites.

Key Materials and Equipment:

- Ultrasound System: B-mode ultrasound machine with a high-frequency linear array transducer (e.g., 12-17 MHz) for high-resolution imaging [11] [12].

- Coupling Gel: A thick layer of water-soluble gel is used to eliminate compression artifacts by ensuring no direct pressure is applied to the site by the transducer [13] [14].

- Anatomical Markers: For consistent site relocation.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Participant Preparation: Position the participant according to the study protocol (e.g., lying down, sitting). Ensure the anatomical site is relaxed and accessible.

- Site Identification and Marking: Identify and mark measurement sites using standardized bony landmarks to reduce inter-subject variability [11]:

- Abdomen: Midway between the umbilicus and the iliac crest.

- Thigh: Mid-section on the anterior thigh between the iliac crest and the top of the patella.

- Arm: Rear upper arm, mid-way between the acromion and olecranon processes.

- Image Acquisition: Apply a generous amount of coupling gel to the marked site. Place the transducer perpendicular to the skin surface without compressing the tissue. Capture a clear cross-sectional image showing the distinct layers: the epidermis/dermis (skin), the hypoechoic subcutaneous adipose tissue, and the underlying muscle fascia [15].

- Thickness Measurement: Using the ultrasound machine's calibrated caliper function:

- Data Recording: Record multiple measurements at each site to calculate a mean value and ensure reliability.

Objective: To evaluate structural changes in the skin and subcutaneous tissue resulting from repeated insulin injections without adequate site rotation.

Key Materials and Equipment:

- Ultrasound System (as described in Protocol 1).

- Skin Biopsy Kit for histological analysis (optional, for deep mechanistic studies).

- Staining Materials: Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) for general histology; Congo Red for amyloid detection; antibodies for immunohistochemical analysis (e.g., anti-insulin antibody) [16].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Cohort Selection: Recruit insulin-treated patients with and without palpable skin abnormalities (e.g., subcutaneous nodules, induration) at their injection sites [16].

- Site Examination: For each participant, perform ultrasonography on both the abnormal injection site and a contralateral or distant normal, non-injected control site using Protocol 1 [16].

- Image Analysis: Quantify and compare skin thickness and SAT thickness between the normal and affected sites. Note any changes in tissue layering structure and echo brightness [16].

- Histological Confirmation (Optional): In a subset of participants, perform a skin biopsy on the indurated site. Process and stain the tissue sections to identify pathological features such as thickened collagen bundles, amyloid deposits, and the presence of insulin-derived material [16].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our ultrasound measurements of subcutaneous fat thickness are inconsistent. What are the primary sources of error and how can we mitigate them? [13] [15] [14]

- Problem: High variability in repeated measurements.

- Solution:

- Avoid Tissue Compression: This is a critical error. Use a thick layer of US gel as a standoff between the probe and skin to prevent deformation of the compressible fat layer, which can reduce thickness by 25-37% [14].

- Standardize Site Mapping: Use a systematic body mapping approach with precisely defined anatomical landmarks relative to body height to ensure consistency across measurements and studies [13].

- Operator Training: The technique is operator-dependent. Ensure all technicians undergo standardized training to achieve high inter- and intra-observer reliability, with target errors of less than 0.15 mm [13].

Q2: We observe unexplained variability in insulin absorption pharmacokinetics in our pre-clinical models. Could injection site characteristics be a factor? [17] [16] [18]

- Problem: Erratic insulin absorption profiles.

- Solution:

- Confirm SC Placement: Intramuscular injection leads to faster, more variable absorption. Use shorter needles (e.g., 4-5 mm) to minimize this risk [18].

- Screen for Lipohypertrophy: Visually inspect and palpate injection sites. Injecting into areas of lipohypertrophy (LH) significantly impairs and variates insulin absorption. Ensure systematic site rotation in study protocols to prevent LH [8].

- Account for SC Thickness: The inverse relationship between SC tissue thickness and insulin absorption rate is well-established. Stratify subjects or animal models by BMI and measure local SC thickness, as thicker adipose layers are associated with tempered insulin absorption [18].

Q3: How does the participant's posture during an injection study affect the relevance of our skin thickness measurements? [19]

- Problem: Measured skin thickness may not reflect real-world conditions.

- Solution:

- Simulate Actual Injection Conditions: Measure skin and SC thickness with the participant in their typical injection posture (e.g., sitting for abdominal injections). Evidence shows that average abdominal skin thickness measured while sitting (3.3 mm) is significantly greater than when measured lying down (2.2 mm), which could impact the risk of intradermal injection with shorter needles [19].

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

SC Tissue Variation Factors

Tissue Change Assessment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|

| High-Frequency Linear Ultrasound Probe (12-18 MHz) | Provides high-resolution imaging for accurate differentiation of skin, subcutaneous fat, and muscle layers. Essential for precise thickness measurements with technical accuracy as high as 0.1 mm [13] [15] [14]. |

| Agarose/Gelatin-Based Tissue Phantoms | Custom-fabricated phantoms with known layer thicknesses simulate skin, SAT, and muscle. Used to validate ultrasound measurement protocols, test new algorithms for automated boundary detection, and train technicians [14]. |

| Anti-Insulin Antibody (Monoclonal) | Used in immunohistochemical staining of biopsy specimens from injection sites to confirm the presence and localization of insulin-derived amyloid deposits, a key pathological finding in injection site reactions [16]. |

| Congo Red Stain | A histological dye used to detect amyloid deposits in tissue sections. Shows apple-green birefringence under polarized light, confirming the diagnosis of injection-localized amyloidosis [16]. |

| Standardized Site Mapping Chart | A template or digital tool based on relative body distances (e.g., percentages of height) to ensure consistent and reproducible identification of measurement sites across all subjects in a longitudinal study [13]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do formulation excipients like zinc and phenol directly influence insulin oligomerization kinetics? Zinc ions and phenolic compounds (e.g., metacresol) are critical excipients that stabilize the insulin hexamer, significantly altering its dissociation kinetics. Zinc coordinates with HisB10 on insulin dimers to form a toroidal hexamer structure [20]. Phenolic ligands, such as phenol or metacresol, induce a conformational change in the hexamer from the T-state (tense) to the R-state (relaxed), forming a markedly more stable complex (T3R3) [21] [20]. This stabilization can have a profound effect on disassembly rates; for instance, a single amino acid substitution (TyrB26→Trp) designed to enhance aromatic interactions at the dimer interface, when combined with these excipients, resulted in a 150-fold increase in hexamer half-life in vitro compared to the wild-type control [21].

Q2: What is the experimental evidence for alternative insulin assembly pathways beyond the classic monomer-dimer-hexamer model? Recent single-molecule studies have directly observed that insulin oligomerization can operate via multiple pathways, not just monomeric additions. The research quantified the existence and abundance of assembly and disassembly pathways involving the addition of monomeric, dimeric, or tetrameric insulin species [20]. The pathway taken is rerouted by solution conditions and excipients. For example, the presence of Zn²⁺ and phenol shifts the pathway to favor dimeric or tetrameric additions, thereby enhancing hexamer formation and stability. This direct evidence revises the oversimplified classical model and explains the high abundance of oligomers across a wide concentration range [20].

Q3: Why does intramuscular (IM) insulin injection lead to greater absorption variability compared to subcutaneous (SC) injection, and how does this impact research? Intramuscular injection leads to faster and more variable absorption because muscle tissue has a higher density of blood vessels and greater blood flow, especially during physical activity, compared to subcutaneous adipose tissue [22] [18]. One study found that the day-to-day (intrapatient) coefficient of variation for the absorption rate (T50%) of NPH insulin was significantly higher for IM injections (29.8%) than for SC injections (18.4%) [22]. For researchers, this highlights that inadvertent IM delivery is a major confounding variable in absorption studies. Ensuring true SC injection through validated techniques (e.g., using shorter needles, ultrasound guidance) is critical for obtaining reproducible pharmacokinetic data [22] [18] [23].

Q4: How can excipients be manipulated to create a stable, ultra-rapid acting insulin formulation rich in monomers? Creating a stable, monomer-rich formulation requires the strategic removal of excipients that promote oligomerization and their replacement with agents that stabilize the monomer. A proven strategy involves:

- Removing Zinc: Eliminating Zn²⁺ prevents the coordination that stabilizes hexamers [24].

- Replacing Phenolic Preservatives: Substituting metacresol with a non-phenolic antimicrobial agent like phenoxyethanol prevents stabilization of the R6 hexamer state [24].

- Adding a Stabilizing Polymer: Incorporating an amphiphilic acrylamide copolymer excipient (e.g., poly(acryloylmorpholine-co-N-isopropylacrylamide), or "MoNi") provides stability to the monomeric and dimeric forms [24]. This specific excipient combination has been shown to yield a formulation containing about 70% insulin monomers that is twice as stable as commercial rapid-acting analogs in stressed aging tests [24].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Variable Insulin Absorption Rates inIn VivoModels

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Inconsistent Injection Depth. Intramuscular vs. subcutaneous delivery results in significantly different pharmacokinetics [18].

- Solution: Standardize injection protocols. Use shorter (e.g., 4-5 mm) needles to minimize risk of IM injection. For preclinical studies, consider ultrasound guidance to verify subcutaneous placement [18] [23].

- Cause 2: Site-to-Site Variability. Absorption rates differ between anatomical sites (abdomen > arm > thigh > buttock) due to variations in blood flow and subcutaneous tissue properties [25].

- Solution: Use a single, standardized injection site (e.g., abdomen) for a given study arm to reduce inter-injection variability.

- Cause 3: Local Tissue Status. Lipohypertrophy (fatty lumps from repeated injections) or local temperature changes can drastically alter absorption [18] [25].

- Solution: Rotate injection sites systematically within the approved anatomical area. Monitor and control ambient temperature at the injection site.

Problem: Unexpectedly Slow or Fast Hexamer Dissociation inIn VitroAssays

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Unaccounted for Excipients. Trace amounts of zinc or phenolic preservatives in commercial insulin can profoundly skew oligomerization kinetics.

- Solution: Pre-treat insulin with chelating agents (e.g., EDTA) to remove zinc, and use size-exclusion chromatography to buffer exchange and remove preservatives prior to assay setup [24]. Precisely document and control all excipients in your experimental buffer.

- Cause 2: Assay Concentration Range. The oligomerization pathway is concentration-dependent. The abundance of different oligomers shifts across the nM to mM range [20].

- Solution: Use an assay appropriate for your target concentration. Single-molecule techniques (e.g., TIRF) are reliable at nM concentrations, while bulk assays (e.g., DLS, AUC) are better for µM-mM ranges [20].

Quantitative Data on Insulin Oligomerization

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Hexamer Dissociation Half-Lives

Data adapted from Brader et al., 2018 [21]

| Insulin Analog | Key Modification / Feature | Excipients Present | Half-life (t½, min ± S.D.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wildtype (WT) | Native human insulin | Zinc, Phenol | 7.7 (± 1.3) |

| Lispro | Weakened dimer interface | Zinc, Phenol | 4.6 (± 0.3) |

| OrnB29 | Semisynthesis-compatible control | Zinc, Phenol | 8.2 (± 0.8) |

| TrpB26, OrnB29 | Enhanced aromatic cluster | Zinc, Phenol | ~1200 (± 300) |

Table 2: Impact of Formulation Excipients on Insulin Association State

Data synthesized from Ma et al., 2022 [24]

| Formulation Base | Zinc | Phenolic Preservative (e.g., Metacresol) | Alternative Preservative | Stabilizing Polymer (MoNi) | Predominant Association State(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial (e.g., Humalog) | Yes | Yes | No | No | Hexamer / Dimer |

| Zinc-Free Lispro-1 | No | Yes | No | Yes | Hexamer / Dimer |

| Zinc-Free Lispro-2 | No | Reduced | Phenoxyethanol | Yes | Mixed |

| Zinc-Free Lispro-3 | No | No | Phenoxyethanol | Yes | Monomer / Dimer |

| Zinc-Free RHI (Regular Human Insulin) | No | No | Phenoxyethanol | Yes | Hexamer |

Standard Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Insulin Oligomerization State via Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC)

Objective: To determine the relative proportions of monomers, dimers, and hexamers in an insulin formulation. Methodology [24]:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare insulin samples at a standard concentration (e.g., 3.45 mg/mL or 100 U/mL) in the desired buffer with excipients.

- Instrument Setup: Use a preparative ultracentrifuge with an An-50 Ti analytical rotor. Set temperature to 20°C and speed to 45,000 rpm.

- Data Acquisition: Acquire data over 200 scans. Analyze data using software such as SEDFIT, employing the c(s) continuous size distribution model.

- Data Analysis: Identify oligomeric states based on their sedimentation coefficients (s). The stoichiometry (N) can be estimated from the monomer sedimentation coefficient (s1) using the relationship: (sN / s1)^(3/2). Typical ranges are:

- Monomer: s ~ 1.0-2.0 S

- Dimer: s ~ 2.5-3.5 S

- Hexamer: s > 5.0 S

Protocol 2: Measuring Hexamer Dissociation Kinetics via Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)

Objective: To monitor the rate of dissociation of insulin hexamers into smaller oligomers under conditions that destabilize the hexamer. Methodology (adapted from [21]):

- Sample Formulation: Formulate insulin with ZnCl₂ (e.g., 2 Zn²⁺ ions per hexamer) and phenol to stabilize the R6 hexamer state.

- Chromatography: Inject the stabilized sample onto an SEC column pre-equilibrated with a zinc- and phenol-free mobile phase.

- Monitoring Dissociation: The change from the mobile phase triggers hexamer disassembly. Monitor the elution profile over time.

- Data Analysis: The chromatogram will show peaks corresponding to different oligomeric states (hexamers, dimers, monomers). The rate of disappearance of the hexamer peak and the appearance of smaller oligomer peaks can be used to calculate dissociation rate constants and half-lives.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram: Insulin Oligomerization Pathways and Excipient Influence

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Oligomer State Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating Insulin Oligomerization

Compiled from multiple sources [21] [24] [20]

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Zinc Chloride (ZnCl₂) | Stabilizes tetramer and hexamer formation via coordination with HisB10. | Creating pharmaceutical-like, stable hexameric insulin for baseline dissociation studies [20]. |

| Phenol / m-Cresol | Phenolic preservatives that induce T→R state transition, dramatically increasing hexamer stability. | Studying the R6 hexamer state and its dissociation kinetics [21] [24]. |

| Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) | Chelating agent that binds Zn²⁺ and other divalent cations. | Removing zinc from commercial formulations to create zinc-free insulin for monomer/dimer studies [24]. |

| Phenoxyethanol | Non-phenolic antimicrobial agent. | Replacing m-cresol in formulations to prevent hexamer stabilization without compromising sterility [24]. |

| Amphiphilic Acrylamide Copolymer (MoNi) | Stabilizing excipient for monomeric/dimeric insulin. | Developing and studying ultra-rapid, stable monomeric insulin formulations [24]. |

| Fluorescent Dye (e.g., ATTO655) | Covalent label for single-molecule detection. | Labeling insulin at sites like LysB28 for real-time tracking of oligomerization via TIRF microscopy [20]. |

Best Practices in Injection Technique and Device Technology to Ensure Subcutaneous Deposition

FAQs: Needle Length and Intramuscular Injection Risk

Q1: What is the primary clinical risk of using a needle that is too long for subcutaneous insulin delivery?

The primary risk is unintentional intramuscular (IM) injection. Insulin delivered into muscle is absorbed more quickly and completely than from subcutaneous tissue, which can lead to unpredictable blood glucose levels and an increased risk of hypoglycemia. This absorption variability is a significant confounder in clinical trials aiming to study the pharmacokinetics of new insulin formulations [26].

Q2: Why is the 4mm pen needle recommended as the standard length for the vast majority of patients?

A 4mm needle is sufficient to reach the subcutaneous tissue in individuals of all body mass indices (BMIs) while minimizing the risk of intramuscular injection. This promotes consistent, predictable absorption and glycemic control. Longer needles do not provide additional therapeutic benefit for subcutaneous delivery and increase the risk of IM injection, especially in leaner individuals [26].

Q3: How does preventing intramuscular injection contribute to more robust research data in drug development?

Unintended IM injection introduces significant variability in insulin absorption rates. By standardizing the use of 4mm needles, researchers can minimize this procedural variable, leading to cleaner data and more accurate assessment of a new insulin product's true pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile [26].

Q4: What are the evidence-based techniques to further reduce injection pain and variability?

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have identified several techniques that reduce IM injection pain, which can be applied to insulin injections. The evidence supports applying manual pressure or rhythmic (Helfer) tapping at the injection site before and during the injection. Furthermore, injections administered in the ventrogluteal site have been shown to be less painful than those in the dorsogluteal site [26].

Troubleshooting Guide for Researchers

Issue: Unexplained Variability in Insulin Absorption Data

This guide is designed to help researchers identify and correct for factors that introduce variability in insulin absorption data during clinical trials.

| Investigation Step | Purpose & Methodology | Interpretation of Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Verify Injection Technique | Ensure consistent subcutaneous delivery. Method: Train staff/participants on proper 4mm needle use with a 90-degree angle; utilize ultrasound imaging on a subset to confirm needle tip placement. | Ultrasound confirmation of IM placement identifies a major source of absorption variability and supports the need for technique re-training. |

| Analyze by Injection Site | Identify site-specific absorption differences. Method: In a controlled sub-study, systematically rotate and document injection sites (abdomen, thigh, arm) and compare pharmacokinetic (PK) curves. | Significant differences in PK parameters (e.g., T~max~, C~max~) between sites confirms site-specific absorption as a key variable. |

| Review Technique & Pain Metrics | Correlate procedure with patient-reported outcomes. Method: Implement standardized pain scales (e.g., Visual Analogue Scale) immediately post-injection and analyze against absorption data. | Reports of higher pain may correlate with quicker absorption, potentially indicating IM injection or nerve contact, highlighting the need for technique refinement [26]. |

| Control for Tissue Morphology | Account for the impact of subcutaneous fat thickness. Method: Use anthropometric measurements or imaging to categorize subjects and perform stratified analysis of PK data. | Increased variability in absorption for subjects with lower subcutaneous fat thickness provides strong evidence for the 4mm needle standard. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating Needle Length Sufficiency via Ultrasound Imaging

Objective: To empirically verify that a 4mm pen needle consistently achieves subcutaneous deposition without risking intramuscular injection across a diverse patient population.

Methodology:

- Participant Recruitment: Recruit a cohort of participants with a wide range of BMIs.

- Imaging Setup: Mark potential injection sites (abdomen, thigh). Use a high-frequency linear ultrasound transducer to visualize the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscle layers. Measure the skin-to-muscle distance.

- Needle Insertion: Insert a 4mm pen needle adjacent to the transducer at a 90-degree angle.

- Data Collection: Capture ultrasound video and still images to document the final position of the needle tip relative to the muscle fascia.

- Data Analysis: Correlate BMI, subcutaneous tissue thickness, and the success rate of subcutaneous placement without muscle penetration.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Absorption Variability in a Crossover Study

Objective: To compare the pharmacokinetic variability of insulin after administration with 4mm needles versus longer needles (e.g., 8mm or 12mm).

Methodology:

- Study Design: A randomized, double-blind, crossover study where each participant receives standardized doses of insulin using both 4mm and longer needles in different study periods.

- Procedure: Administer insulin under fasting, standardized conditions. Injections should be performed by trained professionals at the same anatomical site.

- Blood Sampling: Conduct frequent serial blood sampling to measure serum insulin concentrations and/or glucose infusion rates (euglycemic clamp technique) over a period of 6-8 hours.

- Data Analysis: Calculate key PK parameters including Time to maximum concentration (T~max~), Maximum concentration (C~max~), and Area Under the Curve (AUC). The primary outcome is the coefficient of variation (CV) for these parameters between the two needle-length groups. A lower CV with the 4mm needle would demonstrate reduced variability [27].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials for conducting research on injection depth and insulin absorption.

| Item | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|

| 4mm Insulin Pen Needles | The intervention being studied; the standard for ensuring consistent subcutaneous delivery and minimizing IM injection risk in all patients. |

| High-Frequency Ultrasound System | To objectively measure subcutaneous adipose tissue thickness and visually confirm needle tip placement (subcutaneous vs. intramuscular) during method validation. |

| Pharmacokinetic (PK) Assay Kits | (e.g., ELISA or similar) For measuring serial serum insulin concentrations to generate PK profiles and calculate variability metrics (AUC, C~max~, T~max~). |

| Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) | A standardized tool (typically a 100mm line) for subjects to quantitatively report injection-associated pain, allowing correlation with injection technique and depth. |

| Euglycemic Clamp Apparatus | The "gold standard" method for measuring insulin sensitivity and pharmacodynamics; involves controlled IV glucose infusion to maintain a fixed blood glucose level, providing a direct measure of insulin action. |

Research Methodology Visualization

ERS: Insulin Absorption Variability Study

ITV: Injection Technique Investigation

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is preventing intramuscular (IM) insulin injection a critical consideration in pharmacokinetic research? Intramuscular injection of insulin leads to faster and more erratic absorption compared to subcutaneous (SC) delivery [8]. This variability is a significant confounder in pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) studies, as it can precipitate hypoglycemia and result in inconsistent glucose control, thereby compromising the reliability of data on insulin action and bioavailability [8].

Q2: What is the evidence-based recommendation for insulin injection angle? Current expert consensus recommends a 90-degree (perpendicular) angle for the vast majority of injections using 4mm, 5mm, and 6mm needles [8]. This technique, when performed without a skinfold in appropriate patients, ensures consistent deposition into the subcutaneous tissue. Angled injections are generally not recommended with modern short needles.

Q3: How does needle length influence the decision to pinch a skinfold? Needle length is the primary determinant for the pinching technique. The following table summarizes the core recommendations:

| Needle Length | Recommended Technique | Key Rationale & Patient Demographics |

|---|---|---|

| 4 mm | Do not pinch for most adults [8]. | Sufficient to traverse skin, minimal IM risk. Suitable for all BMIs [8]. |

| Pinch for very thin adults (BMI <19 kg/m²) and children ≤6 years [8]. | Ensures SC delivery in individuals with reduced SC fat thickness [8]. | |

| 5 mm | Pinch is recommended [8]. | Provides an additional safety margin to avoid IM injection [8]. |

| 6 mm | Pinch and inject at a 45° angle [8]. | The angled injection effectively reduces the delivery depth to approximately 4 mm [8]. |

| 8 mm+ | Use is strongly discouraged; switch to a shorter needle [8]. | High risk of IM injection, more painful, and no glycemic benefit [8]. |

Q4: What are the most common errors in insulin injection technique that can introduce variability in research settings? The most prevalent errors that negatively impact insulin absorption and increase data variability are:

- Needle Reuse: Leads to lipohypertrophy (LH), increased pain, and inconsistent dosing [28] [8].

- Failure to Rotate Sites: The primary cause of LH, which alters insulin pharmacokinetics and can increase glucose variability [28] [8].

- Injecting into Lipohypertrophy: Insulin absorption from LH tissue is slowed and erratic, leading to unexplained hyperglycemia and higher insulin doses [28] [8].

Experimental Protocols for Technique Assessment

Protocol 1: Validating Injection Technique in a Clinical Cohort This methodology is adapted from a cross-sectional study designed to quantify the association between injection technique and glycemic outcomes [28].

- Objective: To determine the correlation between a standardized injection technique score and metabolic parameters (HbA1c, FBS, 2HPP).

- Patient Population: 301 adults with type 2 diabetes using insulin pens for at least 3 months.

- Technique Assessment: A 13-item, researcher-made questionnaire with a total score of 26. The tool's validity was confirmed by endocrinologist review, and reliability was established with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.75 [28].

- Key Assessment Items:

- Needle reuse frequency

- Skin fold formation

- Site rotation practice

- Injection angle

- Needle hold time in skin

- Insulin resuspension (for NPH)

- Data Collection: Disease-related data (HbA1c, FBS) were extracted from medical records. Injection sites were physically examined for lipohypertrophy by a trained diabetes educator [28].

- Statistical Analysis: Data were analyzed using SPSS. Correlation between the total injection score and HbA1c was tested using regression analysis, revealing a significant negative correlation (β = -0.263, P < 0.001) [28].

Protocol 2: Point-of-Care Education and Follow-up (ITPR 2.0 Study) This protocol evaluates the effectiveness of immediate feedback on correcting injection errors [29].

- Objective: To explore the effectiveness of feedback and education at the point of care in improving patients’ insulin injection technique.

- Study Design: Physicians completed a baseline assessment survey for eligible patients. If an error was identified, a pop-up knowledge transfer (KT) prompt based on the Forum for Injection Technique (FITTER) recommendations was triggered, providing immediate, specific feedback [29].

- Intervention: The KT prompts provided verbal feedback and information on best practices related to the specific error identified (e.g., needle reuse, incorrect hold time).

- Follow-up: Patients completed a follow-up survey 1-3 months later (average 34.7 days) to identify changes in their technique [29].

- Outcome Measures: Reduction in the number of technique errors per patient. The study found a modest but significant improvement, with patients reducing an average of one error at follow-up [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function in Research Context |

|---|---|

| 4 mm Insulin Pen Needles | The recommended standard needle for minimizing IM injection risk across diverse patient demographics in clinical trials [8]. |

| Lipohypertrophy (LH) Palpation Protocol | A standardized method for identifying and documenting LH at injection sites, a key variable affecting insulin absorption kinetics [28] [8]. |

| Validated Injection Technique Questionnaire (ITQ) | A standardized tool (e.g., 13-item scale) to quantitatively assess participant adherence to proper injection protocols, allowing for correlation with PK/PD data [28]. |

| Structured Point-of-Care Feedback System | A protocol for delivering immediate, standardized education based on FITTER guidelines to correct technique errors during study visits, minimizing interventional variability [29]. |

Decision Pathway for Injection Technique

The following diagram outlines the logical decision process for selecting the correct insulin injection technique based on patient demographics and needle length, integrating evidence-based recommendations to minimize intramuscular delivery risk.

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Technique Errors

| Clinical or Research Observation | Probable Technique Error | Evidence-Based Correction |

|---|---|---|

| Unexplained hypoglycemia, especially post-injection [8]. | Intramuscular injection [8]. | Switch to a 4mm needle and inject at a 90-degree angle without pinching for most adults [8]. |

| Unexplained hyperglycemia & high glucose variability; presence of rubbery or swollen tissue at injection sites [28] [8]. | Lipohypertrophy (LH) from lack of site rotation and needle reuse [28] [8]. | 1. Avoid LH sites entirely. 2. Implement systematic site rotation. 3. Use needles only once. 4. Regularly inspect and palpate sites [28] [8]. |

| Reports of pain during injection; visible skin backflow [28]. | Needle reuse (blunting the needle) and/or incorrect injection angle [28] [8]. | 1. Educate on single-needle use. 2. Ensure a perpendicular (90°) angle with a 4mm or 5mm needle [28] [8]. |

| Inconsistent PK/PD profiles in a study cohort. | Lack of standardized technique training and validation among participants. | Incorporate a validated injection technique questionnaire and direct observation with immediate feedback at study initiation and follow-ups [28] [29]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequent Infusion Set and Pen Needle Issues

Problem: Unexplained Hyperglycemia Following Infusion Set Change

- Question: After I change my infusion set, my blood glucose frequently spikes and does not respond to correction boluses. What could be causing this, and how can I prevent it?

- Answer: This is a common issue often linked to the infusion set. A spike in glucose after a set change can indicate that the new site is not delivering insulin effectively.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Prime the Set Properly: Ensure both the tubing and the catheter are fully primed with insulin after changing the set to eliminate any air gaps [30].

- Time the Change: Change the infusion set just before a meal and administer a full meal bolus immediately after inserting the new set. This helps verify the system is working and counteracts any initial absorption delay [30].

- Administer a Small Extra Bolus: Consider giving an additional small bolus (e.g., 0.5-1.0 unit) once the new infusion set is in place to account for potential undelivered insulin [30].

- Check for Bent Cannula: Upon removal, inspect the flexible cannula. If it is bent, it can impede insulin flow. To prevent this, choose insertion sites with ample subcutaneous fat, use a shorter cannula, or switch to a steel needle infusion set [30].

Problem: High Variability in Experimental Injection Depths

- Question: In our preclinical studies, we observe high variability in needle penetration depth (NPD) even when using needles of the same labeled length. What factors contribute to this, and how can we control for them?

- Answer: Variability in NPD is significantly influenced by two key factors: the hub design of the pen needle and the force applied against the skin during injection. A conventional "posted-hub" design offers less control over depth compared to a reengineered, flatter hub.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Select an Advanced Hub Design: Utilize a pen needle with a hub engineered to control depth. One study showed a reengineered hub achieved the target 4 mm depth with "significantly less variability" across a range of injection forces compared to posted-hub designs [31].

- Standardize Injection Force: In your experimental protocol, define and control the force applied during injection. Highly variable intra- and inter-operator applied skin forces are a major source of NPD inconsistency [31].

- Consider an Autoinjector Shield: Using a shield-triggered autoinjector can standardize the insertion and has been shown to reduce skin blood perfusion, a marker for tissue trauma, by controlling skin deflection [32].

Problem: Persistent Pain or Discomfort During Injection

- Question: Study participants or end-users report significant pain or discomfort during subcutaneous injection. What needle-related factors can we adjust to improve comfort?

- Answer: Pain can be mitigated through several design and technique modifications focused on the needle's physical characteristics and the injection process itself.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Use a Thinner, Shorter Needle: Research consistently shows that higher-gauge (thinner) needles result in lower reported pain levels. Similarly, using the shortest needle length appropriate for the subcutaneous tissue depth minimizes tissue trauma [33] [34].

- Evaluate the Hub Design: A hard polymer hub can minimize "flexing" during injection, which prevents leakage and potential tissue disturbance that can cause pain [35].

- Implement Cold Needle Technique: A prospective randomized controlled study found that using a needle chilled to 0-2 °C significantly reduced injection pain and increased patient satisfaction compared to a needle at room temperature [36].

- Ensure a Sharp, Multi-Beveled Tip: Needle tips with multiple bevels (e.g., 5 facets) are designed for smoother skin penetration, reducing insertion force and discomfort [34].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How does needle hub design physically influence the consistency of needle penetration depth?

The hub is the polymer base that connects the needle to the syringe or pen. Its geometry determines how it sits against the skin and interacts with tissue during insertion.

- Conventional Posted-Hub: This design features a small cylindrical post that extends from the hub base. This post can indent the skin upon application, allowing the needle to achieve a deeper-than-intended penetration, especially with higher injection forces. This leads to high variability in depth [31].

- Reengineered/Advanced Hub: These hubs are designed with a wider, flatter geometry that distributes pressure more evenly and limits skin indentation. This design effectively "bottoms out" on the skin surface, creating a more reliable stop that ensures the needle reaches the target subcutaneous tissue consistently, regardless of moderate variations in applied force [31].

FAQ 2: Beyond patient comfort, what is the critical research imperative for reducing intramuscular (IM) injection risk?

The primary research imperative is to control experimental variables and ensure accurate drug delivery. An unintended intramuscular injection represents a critical failure in subcutaneous dosing studies.

- Altered Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics (PK/PD): Insulin and many other drugs are absorbed much more rapidly from muscle tissue than from subcutaneous fat. An IM injection can cause a dangerously rapid onset of action and skew PK/PD data, leading to incorrect conclusions about a drug's profile [31].

- Increased Data Variability: Uncontrolled penetration depth is a major source of variability in absorption studies. By using hub designs that ensure consistent subcutaneous delivery, researchers can reduce noise in their data and achieve more reliable and reproducible results [31].

FAQ 3: Are there reusable or multi-use needle designs that are suitable for repeated preclinical testing?

Yes, novel robust needle designs are being developed for multi-use applications. Their suitability depends on the specific requirements of the test.

- Design Principle: These needles feature a reinforced tip geometry, such as larger bevel angles and a pre-bent design, to enhance durability and resist deformation (hooking) after multiple insertions [32].

- Preclinical Evidence: One study showed that a robust needle (EXP) required a force of 5.38 N to form a 33 µm hook, compared to only 0.92 N for a conventional single-use needle (NF30). When tested in a porcine model, this robust needle did not induce more tissue trauma than its single-use counterpart, especially when used with an autoinjector shield [32].

- Application: Such needles are ideal for repeated-dose studies or device durability testing, as they can reduce consumable costs and environmental impact while maintaining experimental integrity.

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from research on needle hubs and related technologies.

Table 1: Impact of Hub Design and Injection Force on Needle Penetration Depth (NPD) and IM Risk

| Hub Design Type | Applied Force (lbf [N]) | Mean Needle Penetration Depth (NPD) | Variability (vs. Target Depth) | Modeled IM Injection Risk (vs. Posted-Hub) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reengineered Hub [31] | 0.25 lbf [1.1 N] | Closer to 4 mm target | Significantly less variability (P = 0.006) | ~2-8 times reduction |

| 0.75 lbf [3.3 N] | Closer to 4 mm target | Significantly less variability (P = 0.006) | ~2-8 times reduction | |

| 1.25 lbf [5.6 N] | Closer to 4 mm target | Significantly less variability (P = 0.006) | ~2-8 times reduction | |

| 2.00 lbf [8.9 N] | Closer to 4 mm target | Significantly less variability (P = 0.006) | ~2-8 times reduction | |

| Commercial Posted-Hub [31] | 0.25 lbf [1.1 N] | Deviated from 4 mm target | Higher variability | Baseline (Higher) |

| 0.75 lbf [3.3 N] | Deviated from 4 mm target | Higher variability | Baseline (Higher) | |

| 1.25 lbf [5.6 N] | Deviated from 4 mm target | Higher variability | Baseline (Higher) | |

| 2.00 lbf [8.9 N] | Deviated from 4 mm target | Higher variability | Baseline (Higher) |

Table 2: Efficacy of Pain Reduction and Needle Robustness Techniques

| Technique / Design | Metric | Result / Effect | Clinical / Research Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cold Needle [36] | Pain Score (VAS) | 21.0 ± 14.46 (Cold) vs. 33.0 ± 18.03 (Room Temp) | Significant reduction in patient-reported pain. |

| Injection Satisfaction Score | 86.33 ± 11.29 (Cold) vs. 73.00 ± 17.04 (Room Temp) | Significant increase in patient satisfaction. | |

| Robust Needle (EXP) [32] | Force to form 33µm hook | 5.38 N (EXP) vs. 0.92 N (Control NF30) | Withstands significantly more mechanical stress, enabling multi-use. |

| Hard Polymer Hub (HPC) [35] | Pressure Resistance | Withstands up to 2.5x more pressure | Prevents hub flexing and leakage, ensuring dose accuracy. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vivo Measurement of Needle Penetration Depth (NPD) Using Fluoroscopy

This protocol is adapted from a preclinical study that quantified the impact of hub design and injection force on penetration depth [31].

- Objective: To precisely measure the in vivo depth a needle reaches in subcutaneous tissue under controlled application forces.

- Materials:

- Animal Model: Yorkshire swine (35-40 kg). Swine skin is structurally and compositionally similar to human skin, providing a valid model [31] [32].

- Devices: Pen needles with different hub designs (e.g., reengineered vs. posted-hub). A standard pen injector (e.g., ClikSTAR).

- Instrumentation: Custom Insertion Force Measurement Tool (IFMT) with a donut load cell. Fluoroscope (e.g., Glenbrook Technologies LabScope).

- Injectate: Iodinated contrast agent (e.g., Omnipaque 350 mg Iodine/ml).

- Methodology:

- Anesthesia and Positioning: Anesthetize the animal and position it under the fluoroscope with the target flank area perpendicular to the X-ray beam path.

- Site Identification: Mark and number an array of injection sites on the flank.

- Force-Targeted Injection: Connect the IFMT between the pen and the needle. For each injection, the operator targets a specific application force (e.g., 0.25, 0.75, 1.25, 2.00 lbf). The IFMT acquires and displays force data in real-time.

- Contrast Administration: Administer a small, controlled volume (e.g., 20 µl) of contrast agent.

- Image Acquisition: Capture a fluoroscopic image immediately after injection to visualize the radio-opaque depot.

- Depth Measurement: Calculate the NPD from the 2D image against a radiopaque scale placed in the field of view, applying a parallax correction factor.

- Analysis: Statistically compare the mean NPD and variability for each hub design across the different force levels. Use an in silico probability model to estimate IM injection risk based on NPD data and human tissue thickness measurements.

Protocol 2: Assessing Injection Site Trauma via Skin Blood Perfusion (LASCA)

This protocol assesses tissue trauma, a proxy for pain and tissue damage, resulting from different needle designs [32].

- Objective: To quantify local tissue trauma induced by needle insertion by measuring changes in skin blood perfusion (SBP).

- Materials:

- Animal Model: Landrace, Yorkshire, and Duroc (LYD) pigs.

- Devices: Test needles (e.g., novel robust needle, conventional control needles), autoinjector shields.

- Instrumentation: Laser Speckle Contrast Analysis (LASCA) system. Handheld digital force gauge.

- Methodology:

- Site Preparation: Shave the pig's neck area one day before the experiment. On the day, mark a grid of insertion sites.

- Needle Insertion: Perform needle insertions according to the experimental plan (e.g., different needles, with/without shield, various applied forces). Use a force gauge to standardize shield pressure.

- LASCA Imaging: Use the LASCA system to scan the insertion area immediately after needle removal. The system measures microcirculatory blood flow by analyzing the speckle pattern of laser light.

- Blinding: The operator performing insertions and analysis should be blinded to the needle type to prevent bias.

- Analysis: Compare the SBP values between different needle groups. A higher SBP indicates greater tissue trauma and a stronger inflammatory response.

Experimental Workflow and Logical Diagrams

Diagram 1: NPD Evaluation Workflow

Diagram 2: Logic of Injection Variability

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Needle Hub and Injection Depth Research

| Item | Function / Application in Research | Key Specification / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Yorkshire Swine Model [31] | In vivo model for injection studies. | Skin structure, elasticity, and SC tissue thickness are highly analogous to humans. |

| Insertion Force Measurement Tool (IFMT) [31] | Precisely measures and controls the force applied against the skin during injection. | Critical for standardizing one of the most significant human factors (force) in injection depth studies. |

| Fluoroscope with Contrast Agent [31] | Enables real-time visualization and measurement of needle tip depth and injectate depot location. | Provides direct, quantitative data on Needle Penetration Depth (NPD). |

| Laser Speckle Contrast Analysis (LASCA) [32] | Quantifies local skin blood perfusion (SBP) as a non-invasive marker for needle-induced tissue trauma. | Offers an objective, preclinical measure of tissue damage and potential pain. |

| Reengineered Hub Pen Needles [31] | The independent variable in studies aiming to control injection depth. | Designed with a wider, flatter geometry to limit skin indentation and reduce NPD variability. |

| Autoinjector Shields [32] | Used to standardize the insertion angle and control skin deflection during automated injections. | Helps isolate the effect of needle design from user technique and can reduce tissue trauma. |

Systematic Site Rotation Protocols to Prevent Tissue Complications and Ensure Consistent Absorption

For researchers and drug development professionals, the subcutaneous (SC) space represents a critical interface for the delivery of biotherapeutics, particularly insulin. The integrity of this tissue is paramount for ensuring consistent pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) profiles of administered drugs. Lipohypertrophy (LH)—the localized hypertrophy of subcutaneous fat—is a frequent tissue complication that significantly alters drug absorption, leading to unpredictable glycemic outcomes in clinical trials and unreliable PK/PD data in pre-clinical studies [8] [37]. Systematic site rotation is a foundational methodology to preserve tissue health and ensure the reproducibility of absorption data. This guide provides troubleshooting and protocols to standardize this crucial aspect of preclinical and clinical research.

Understanding the Problem: Lipohypertrophy and Research Outcomes

The Impact of Lipohypertrophy on Drug Absorption

Lipohypertrophy is more than a clinical nuisance; it is a significant confounding variable in research settings. Injecting into LH tissue leads to:

- Erratic Absorption: Insulin absorption from LH sites is slowed and highly variable, increasing intrasubject variability and compromising data integrity [8] [37].

- Reduced Drug Action: The glucose-lowering effect of insulin is blunted and unpredictable when administered into LH [8] [38].

- Increased Resource Consumption: Studies note that subjects with LH may require a mean of over 10 IU more insulin per day to achieve glycemic control, directly impacting study dosing and cost calculations [38].

Pathophysiology and Histology

Histological analysis of LH tissue reveals a disrupted architecture, explaining the altered absorption kinetics. Affected areas show:

- Macro-adipocytes: Approximately 75% of the SC tissue is composed of enlarged fat cells compared to normal adjacent adipocytes [37].

- Fibrosis: Increased presence of fibrotic tissue, which may physically impede the diffusion and absorption of therapeutic agents [37].

- Altered Vascularization: The normal capillary network may be compromised, directly affecting the pathway of insulin into the bloodstream [18].

The following diagram illustrates the stark difference in insulin absorption pathways between healthy and lipohypertrophic subcutaneous tissue.

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: What are the primary risk factors for lipohypertrophy in a research cohort?

Answer: The development of LH is primarily technique-dependent. Key risk factors identified in large surveys and clinical studies include [8] [37] [38]:

- Lack of Systematic Site Rotation: Failure to rotate injection sites is the most significant factor.

- Needle Reuse: Reusing pen or syringe needles causes increased tissue trauma and is strongly correlated with LH.

- High Injection Frequency: A greater number of daily injections into a limited area elevates risk.

- Large Injection Volumes: Administering large volumes per injection (>50 µL) may contribute to tissue trauma.

- Incorrect Needle Length: Using needles that are too long can increase the risk of intramuscular injection and deeper tissue damage.

FAQ 2: How can we accurately detect and monitor lipohypertrophy in study subjects?

Answer: A multi-modal approach is recommended for rigorous data collection.

Method 1: Visual Inspection and Palpation

- Protocol: Visually inspect and gently palpate the entire injection area with clean hands. Have the subject change body position (e.g., rotate torso) to make subtle LH more visible. A "pinching" maneuver helps identify elastic, non-visible nodules [37].

- Limitations: Subject to examiner experience. One study showed trained professionals are 45% more likely to correctly detect LH than untrained staff [37].

Method 2: High-Frequency Ultrasound

- Protocol: Utilize ultrasound imaging to obtain cross-sectional views of the subcutaneous tissue. LH appears as hyperechoic (brighter) regions with altered architecture [37].

- Advantages: Approximately 30% more sensitive than palpation. It can detect deeper structural changes before they are visible or palpable, providing objective, quantifiable data for longitudinal studies [37].

Troubleshooting Table: Common Injection Site Issues and Research Impact

| Problem | Underlying Mechanism | Impact on Research Data | Corrective Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipohypertrophy (LH) | Repetitive trauma & anabolic effect of insulin causing macro-adipocytes & fibrosis [37]. | Highly variable PK/PD; increased insulin dose requirements; unreliable glucose response curves [8] [38]. | Implement strict site rotation; prohibit needle reuse; use ultrasound for detection; avoid injecting into affected areas. |