Optimizing Glycemic Control: A Scientific Review of Injection Site Rotation for the Prevention of Insulin-Associated Lipodystrophy

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and clinical scientists on the critical role of injection site rotation in preventing lipodystrophy, a common complication of insulin therapy.

Optimizing Glycemic Control: A Scientific Review of Injection Site Rotation for the Prevention of Insulin-Associated Lipodystrophy

Abstract

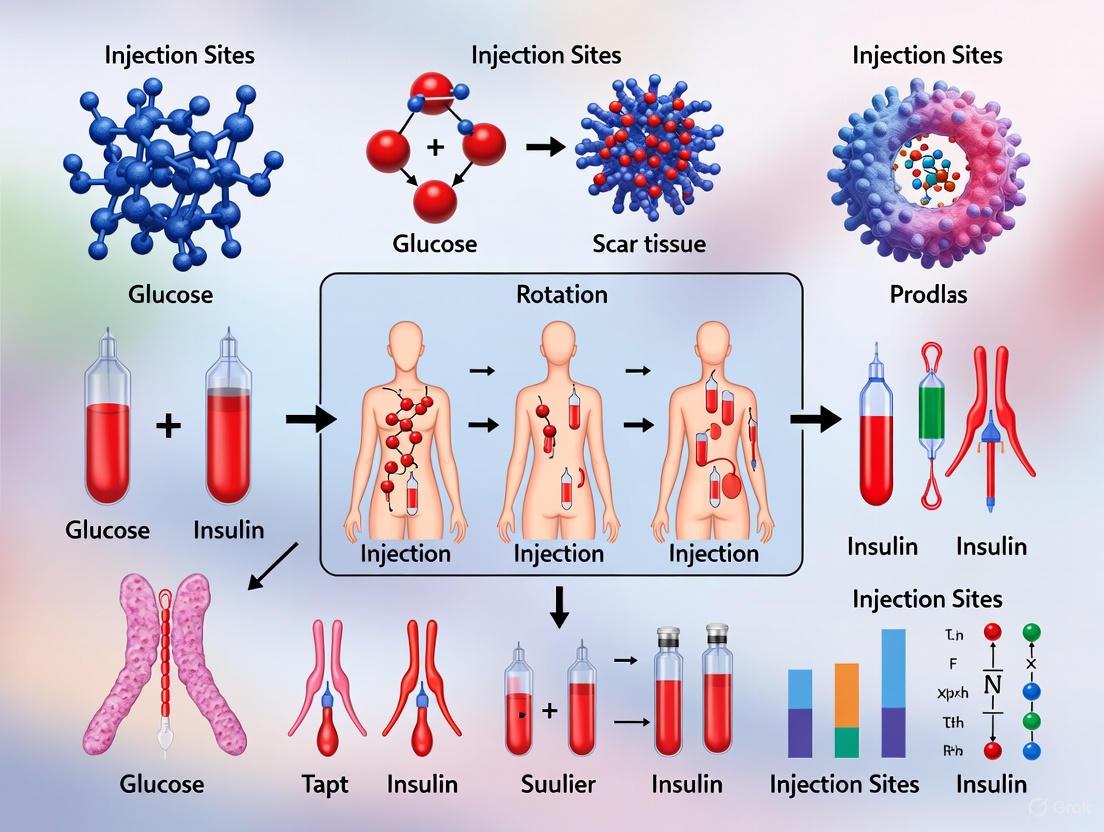

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and clinical scientists on the critical role of injection site rotation in preventing lipodystrophy, a common complication of insulin therapy. We explore the underlying pathophysiology of lipohypertrophy, its significant impact on glycemic variability and insulin pharmacokinetics, and the barriers to effective prevention. The content systematically reviews evidence-based injection protocols, advanced detection methodologies including ultrasound, and evaluates the efficacy of structured educational interventions. By synthesizing current evidence and identifying research gaps, this review aims to inform both clinical practice and the development of next-generation insulin delivery systems.

The Pathophysiology and Clinical Impact of Insulin-Associated Lipohypertrophy

Definition and Clinical Significance

Lipohypertrophy (LH) is defined as a tumor-like lump, visible and touchable, comprising swollen adipose tissue at the site of repeated insulin injection [1]. It represents the most prevalent local cutaneous complication of insulin therapy, with reported prevalence in insulin-treated individuals ranging from 11.1% to 73.4%; recent studies in China report rates from 53.1% to 73.4% [1]. This pathology is characterized by the proliferation of adipose tissue and manifests as subcutaneous nodular swelling due to adipose tissue proliferation at injection sites [2]. Histological examination reveals that LH tissue contains a significantly larger number of macro-adipocytes and fibrosis compared to normal adipose tissue [3].

The clinical impact of LH is profound. Injecting insulin into lipohypertrophic tissue significantly impairs insulin absorption, leading to marked hyperglycemia and substantial glycemic variability [2] [1]. This disrupted absorption results in a separation of post-meal blood glucose curves after 30 minutes, leading to significant differences in blood glucose levels from 2 hours onwards and in maximum postprandial blood glucose concentrations [1]. Conversely, when patients subsequently inject their usual insulin dose into unaffected tissue, the risk of unpredictable and severe hypoglycemia increases substantially [3] [1]. These glycemic excursions contribute to poor long-term metabolic control and increased risk of diabetes complications.

Table 1: Epidemiological and Clinical Characteristics of Lipohypertrophy

| Characteristic | Details |

|---|---|

| Global Prevalence in Insulin Users | 11.1% - 73.4% (average ~41.8%) [2] [1] |

| Reported Prevalence in China | 53.1% - 73.4% [1] |

| Primary Etiology | Repeated insulin exposure to subcutaneous tissue [2] [1] |

| Key Histological Features | Macro-adipocytes, fibrosis, dense fibrous texture [3] [1] |

| Impact on Insulin Pharmacokinetics | Slower, unpredictable absorption [1] |

| Key Clinical Consequences | Glycemic variability, unexplained hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, increased insulin requirements [2] [3] [1] |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs for Researchers

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the primary cellular mechanisms driving lipohypertrophy development? The pathophysiology of insulin-related LH is not fully elucidated, but several mechanisms have been proposed. The predominant theory suggests insulin's anabolic effect on local adipocytes promotes the synthesis of fats and proteins, leading to adipose tissue expansion [1]. Some evidence suggests that anti-insulin antibody levels show a positive relationship with LH, indicating possible immunological factors [1]. Histological studies show that areas with insulin-induced LH contain a significantly larger number of macro-adipocytes and fibrosis compared to normal adipose tissue [3].

Q2: Why does insulin absorption become impaired in lipohypertrophic tissue? The structural properties of LH tissue, characterized by thickened, hard, elastic adipose tissue with large adipocytes and dense fibrous texture, create a physical barrier that makes insulin release slower and more unpredictable [1]. The fibrotic components likely disrupt normal capillary perfusion and create diffusion barriers, leading to blunted and more variable insulin absorption and action, ultimately impairing postprandial glucose control [1].

Q3: What are the key risk factors for lipohypertrophy development in clinical populations? Major risk factors include failure to rotate injection sites, concentrating injections in a small area, needle reuse, injection of cold insulin, high number of daily injections, large injection volumes, and using long and thick needles [3]. Patient behavior is particularly significant, as individuals often prefer reusing less painful tissue and more promptly accessible sites [1].

Q4: What detection methods are most sensitive for identifying early lipohypertrophy? While conventional diagnosis relies on visual inspection and palpation, these methods exhibit limited effectiveness in detecting flat LH lesions [2]. Ultrasound examination emerges as a superior diagnostic modality, offering approximately 30% greater sensitivity in detecting LH compared to palpation [3]. Ultrasound can reveal structural changes in deeper levels of subcutaneous tissue before any visual surface changes appear [3].

Q5: How can researchers differentiate lipohypertrophy from other injection site reactions? LH typically presents as a soft, spongy, or firm swelling at injection sites, unlike lipoatrophy which presents as dimpling or loss of subcutaneous fat [3] [4]. Histologically, LH demonstrates adipocyte hypertrophy and fibrosis rather than the inflammatory infiltrates or fat destruction seen in other conditions. Ultrasound characterization can precisely differentiate LH from other subcutaneous pathologies by revealing distinct echogenicity patterns and structural changes [3].

Table 2: Key Risk Factors for Lipohypertrophy Development

| Risk Factor Category | Specific Factors | Strength of Association |

|---|---|---|

| Injection Technique | Failure to rotate sites, needle reuse (>3 times), small rotation area | Strong [2] [3] [1] |

| Patient Factors | High BMI, long insulin therapy duration, high HbA1c, hypoglycemia history | Moderate [1] |

| Insulin Formulation | Use of regular insulin (3.2-fold risk vs. rapid-acting) [1] | Moderate |

| Device Factors | Longer/thicker needles, improper technique | Moderate [3] |

Experimental Models and Research Methodologies

Established Research Protocols

Protocol 1: Ultrasound Detection and Characterization of Lipohypertrophy

Ultrasound represents the gold standard for non-invasive LH detection in both clinical and research settings [1]. The protocol should utilize high-frequency linear array transducers (≥12 MHz) for optimal subcutaneous tissue resolution. Examination should include:

- B-mode imaging to assess subcutaneous tissue echogenicity and architechture

- Measurement of subcutaneous layer thickness at both affected and unaffected sites

- Doppler evaluation to assess vascularity within the lesion

- Elastography (where available) to evaluate tissue stiffness

LH typically appears as an increased echo of the subcutaneous tissue, with or without different sizes of definite nodules in the boundary area [1]. Researchers should document the size, shape, echogenicity, and vascularity of all identified lesions. This method is particularly valuable for identifying non-palpable "flat" LH that escapes detection by physical examination [2] [3].

Protocol 2: Histopathological Analysis of Lipohypertrophy

For studies utilizing animal models or human biopsy specimens, comprehensive histological characterization should include:

- Standard H&E staining to assess overall tissue architecture and adipocyte morphology

- Masson's Trichrome or Picrosirius Red staining to quantify collagen deposition and fibrosis

- Immunohistochemistry for adipocyte differentiation markers (PPAR-γ, C/EBP-α) and proliferation markers (Ki-67)

- Scanning electron microscopy to examine adipocyte ultrastructure and extracellular matrix organization

Histology images of LH obtained through scanning electron microscopy have shown that up to 75% of the subcutaneous tissue is composed of macro-adipocytes with significantly larger size than adjacent normal adipocytes, associated with increased fibrosis and apoptosis [3].

Protocol 3: Metabolic Characterization in Preclinical Models

To evaluate the metabolic consequences of LH in animal models:

- Inject insulin exclusively into induced-LH sites and compare pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profiles with normal tissue

- Perform frequent glucose measurements following injection to assess absorption variability

- Conduct hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps to quantify insulin sensitivity

- Measure adipokine profiles (leptin, adiponectin) in serum and tissue

Studies in humans have demonstrated that injection into LH sites results in significant differences in postprandial blood glucose from 2 hours onwards, and in maximum postprandial blood glucose concentrations compared to normal tissue [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Lipohypertrophy Investigation

| Reagent/Material | Application in LH Research | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-frequency Ultrasound Systems (≥12 MHz) | Non-invasive detection and monitoring of subcutaneous tissue changes | Enables precise measurement of lesion size, echogenicity, and evolution over time [3] |

| Collagenase Type I/II | Isolation of stromal vascular fraction (SVF) from adipose tissue | Critical for digesting extracellular matrix to release adipocytes and progenitor cells for in vitro studies [5] |

| Adipocyte Differentiation Media | In vitro modeling of adipogenesis | Typically contains insulin, dexamethasone, IBMX, and indomethacin to induce preadipocyte differentiation |

| Anti-PPAR-γ & C/EBP-α Antibodies | Immunohistochemical analysis of adipocyte differentiation | Key transcription factors regulating adipogenesis; expression patterns altered in LH [6] |

| Masson's Trichrome Stain | Histological quantification of fibrosis | Differentiates collagen (blue/green) from muscle/cytoplasm (red) in tissue sections [3] |

| Human Insulin Preparations | In vitro stimulation of adipocyte cultures | Used to model repeated insulin exposure; regular insulin shows 3.2-fold higher LH risk vs. rapid-acting [1] |

| GLUT4 Translocation Assays | Assessment of insulin signaling integrity | LH tissue demonstrates impaired insulin responsiveness and glucose uptake |

| Cytokine Profiling Arrays | Analysis of inflammatory mediators in LH tissue | LH may involve low-grade inflammation; panels should include TNF-α, IL-6, adiponectin, leptin [5] |

Pathophysiological Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The development of lipohypertrophy involves complex interactions between insulin's biological actions and the subcutaneous tissue response. Several interconnected pathways contribute to its pathogenesis:

Insulin's Anabolic Actions: Insulin exerts direct lipogenic effects on adipocytes, promoting the synthesis of fats and proteins, which drives adipocyte hypertrophy and tissue expansion [1]. This localized trophic effect is amplified by repeated insulin exposure in the same tissue areas.

Fibrotic Remodeling: Histological analysis reveals that LH tissue contains a significantly larger number of macro-adipocytes and fibrosis compared to normal adipose tissue [3]. This fibrotic component develops through the activation of profibrotic genes such as connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and TGF-β signaling components, leading to extracellular matrix accumulation [6].

Mechanical Trauma and Tissue Repair: Repeated needle insertion creates microtrauma that initiates wound healing responses, potentially leading to excessive extracellular matrix deposition and fibrotic remodeling [2]. This process is exacerbated by needle reuse, which dulls needles and increases tissue damage.

Potential Immunological Factors: Some evidence suggests immunological involvement, with studies showing a positive relationship between anti-insulin antibody levels and LH development [1]. The role of immune cell infiltration and localized inflammation warrants further investigation.

Prevention and Management Strategies in Research Context

Understanding LH pathology directly informs prevention strategies, which are particularly relevant for longitudinal studies involving repeated injections in animal models or clinical trials.

Injection Site Rotation Protocols: Systematic rotation of injection sites is fundamental to preventing LH. Research protocols should implement standardized rotation patterns that ensure ≥1 cm spacing between consecutive injections [2]. The recommended anatomical sites include abdominal wall, lateral/posterior arms, anterolateral thighs, and buttocks [2] [7].

Needle Replacement Guidelines: Studies consistently show that needle reuse correlates with increased LH prevalence [3]. Research protocols should specify single-use of disposable needles to minimize tissue trauma [2]. The use of shorter needles (4 mm) is also recommended to reduce deep tissue injury while ensuring consistent subcutaneous delivery [2].

Educational Interventions: Research from clinical settings demonstrates that structured education significantly improves injection technique and reduces LH incidence [8]. In one study of Chinese community nurses, 47.7% had poor insulin injection knowledge, highlighting the need for comprehensive training even among healthcare professionals [8]. Research protocols should include standardized training and periodic reassessment of injection technique.

Monitoring and Early Detection: Regular monitoring of injection sites using standardized palpation techniques or ultrasound can detect early LH formation [2] [3]. The pinching maneuver can aid in identifying less visible, elastic nodules, though ultrasound examination remains the most sensitive detection method, particularly for non-palpable LH [2].

The reversibility of LH with proper injection technique underscores the importance of these preventive measures. With consistent site rotation and avoidance of affected areas, existing LH lesions can gradually resolve over time, restoring normal insulin absorption and metabolic control [1].

Lipohypertrophy (LH), the thickening of fatty tissue at insulin injection sites, represents a prevalent and significant complication in diabetes management. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding its epidemiology and the underlying pathophysiology is crucial for developing advanced insulin formulations and delivery systems. This complication, often overlooked in clinical practice, directly impacts drug absorption kinetics, glycemic control, and therapeutic outcomes, making it a critical area of scientific inquiry within the context of injection site rotation and scar tissue research.

Epidemiology and Prevalence Data

Extensive clinical studies have quantified the significant burden of lipohypertrophy among insulin-treated patients. The table below summarizes key epidemiological findings:

Table 1: Documented Prevalence of Lipohypertrophy in Diabetes Populations

| Study / Population Context | Reported Prevalence | Key Risk Factors Identified |

|---|---|---|

| General diabetes population [9] | Up to 64% | Failure to rotate injection/infusion sites; Low BMI; Reuse of needles; Use of human (vs. analog) insulin |

| Patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes [10] | Up to 62% | Continuous injections at the same site; Injection into areas of scar tissue |

| Global Injection Technique Questionnaire (ITQ) Survey [11] | Nearly 50% | Reusing injection sites for a whole day or even days; Injecting into lipohypertrophic areas (reported by 26% of respondents) |

The high prevalence is largely attributed to persistent suboptimal injection techniques among patients. A major global survey, the Forum for Injection Technique (FITTER) Injection Technique Questionnaire (ITQ), highlighted that nearly 50% of patients exhibit symptoms suggestive of LH, with 21% reporting repeated injections at the exact same site over multiple days [11]. This underscores a critical gap between established clinical guidelines and real-world patient practices.

Pathophysiology and Experimental Models

Underlying Biological Mechanisms

Lipohypertrophy results from the localized trophic effects of insulin repeated injections into the same subcutaneous site [12]. The condition is characterized by:

- Cellular Hypertrophy: Lipohypertrophic fat cells can be approximately twice the size of normal adipocytes, contributing to the visible and palpable lump [9].

- Tissue Composition: The lumps consist of a buildup of fat, protein, and scar tissue [9].

- Absorption Dysregulation: The altered architecture and vascularization of the tissue lead to erratic and unpredictable absorption of insulin [9] [10]. Depending on the injection, insulin release from these sites can be delayed or accelerated, causing glycemic excursions.

This pathophysiology can be conceptually mapped to guide research focus:

Standardized Clinical Assessment Protocol

For consistent evaluation in clinical trials or studies, researchers should employ a standardized diagnostic protocol.

- 1. Patient History: Systematically document injection habits, including duration of insulin use, frequency of site rotation, and needle reuse practices [9] [10].

- 2. Visual Inspection: Examine common injection sites (abdomen, thighs, arms, buttocks) for raised, swollen, or thickened areas of skin. LH can vary in size from a golf ball to a fist [9] [13].

- 3. Palpation: Methodically palpate all potential injection areas. LH typically feels firm, rubbery, or lumpy and is often characterized by reduced sensation or numbness compared to surrounding healthy tissue [9] [10].

- 4. Severity Grading: For facial lipoatrophy (a related condition), a 5-degree scale exists, ranging from discrete flattening to excessive indentation with protruding bone structures [14]. While a universally accepted grading scale for LH is not explicitly detailed in the sources, the principle of classifying severity based on physical characteristics is a key research methodology.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Methods for Lipohypertrophy Research

| Tool / Material | Research Function & Application |

|---|---|

| High-Frequency Ultrasound | High-resolution imaging to non-invasively measure skin thickness, subcutaneous tissue depth, and quantitatively characterize the internal structure of LH lesions [11]. |

| Insulin Analogs | Comparative studies to investigate the mitogenic potency and lipohypertrophic potential of different insulin formulations (e.g., glargine, detemir, degludec) versus human insulin [12]. |

| Histopathological Staining | Analysis of biopsy specimens from LH sites to identify key tissue changes: lobular panniculitis, lymphocytic infiltration, hyaline necrosis of fat lobules, and fibrosis [14]. |

| Patient Injection Technique Questionnaire (ITQ) | Validated survey tool to quantitatively assess patient behaviors related to site rotation, needle reuse, and injection into LH areas, correlating practices with clinical outcomes [11]. |

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ for Research and Clinical Trial Design

Q1: In our clinical trials, we observe significant variability in insulin absorption. Could undiagnosed lipohypertrophy be a confounding factor, and how can we control for it? Yes, LH is a major source of pharmacokinetic variability. Insulin absorption from LH sites is erratic, leading to unpredictable glycemic excursions that can obscure trial results [9] [15].

- Troubleshooting Protocol: Implement a mandatory injection site examination for all trial participants at every study visit. This should include both visual inspection and systematic palpation of all potential injection areas by a trained healthcare professional [10]. Participants found to have LH should be instructed to strictly avoid injecting into affected areas for a minimum of 2-3 months to allow for tissue healing [9].

Q2: Our in-vitro models show differences in IGF-1 receptor affinity between insulin analogs. What is the clinical significance of this for long-term tissue effects like lipohypertrophy? While in-vitro studies indicated that insulin glargine had a higher mitogenic potency and IGF-1 receptor affinity, it is rapidly degraded to metabolites (M1) in the subcutaneous tissue with lower binding affinity [12]. Large-scale human epidemiologic studies and observational studies with up to 7 years of follow-up have not found conclusive evidence of an associated increased risk of malignancy or specific tissue complications like LH compared to other insulins [12]. The long-term clinical significance of differences in IGF-1 binding remains an area of active investigation, highlighting the necessity of robust post-marketing surveillance.

Q3: What are the most critical, evidence-based recommendations we can provide to patients in our studies to prevent lipohypertrophy? The cornerstone of prevention is proper injection technique, which can be standardized in clinical protocols [11]:

- Systematic Site Rotation: Establish and document a formal rotation plan that moves injections/system sites around the body (abdomen, thigh, buttocks, arms) [9] [16].

- Avoid Needle Reuse: Mandate the use of a new needle for every injection. Reused needles cause microtrauma that contributes to tissue damage [9] [17].

- Spatial Separation within a Site: Ensure successive injections in the same general area (e.g., the abdomen) are spaced at least one finger-width (approximately 1-2 cm) apart to prevent over-stimulating a single spot [9].

Q4: How can we objectively measure the resolution of lipohypertrophy in intervention studies? The primary method is the cessation of injections into the affected area and longitudinal monitoring.

- Methodology: Document the size and texture of the LH area via palpation and photography at baseline. Re-examine the area at regular intervals (e.g., monthly). Natural resolution can take months to years [9]. High-frequency ultrasound can be used as an objective tool to track changes in subcutaneous tissue thickness and echogenicity over time [11].

Core Molecular Mechanisms of Insulin

Insulin Synthesis, Structure, and Key Metabolic Functions

Insulin is a peptide hormone essential for energy conservation and utilization, produced by pancreatic beta cells. Its synthesis begins with preproinsulin, which is cleaved in the endoplasmic reticulum to form proinsulin. Further processing removes the C-peptide, yielding the bioactive hormone composed of 51 amino acids arranged in two chains (A and B) linked by disulfide bonds [18] [19]. The primary anabolic effects of insulin are mediated through its binding to the Insulin Receptor (INSR), a receptor tyrosine kinase expressed on the surface of target cells [19]. This interaction triggers a downstream signaling cascade that regulates glucose, lipid, and protein metabolism.

The table below summarizes insulin's key anabolic effects on different metabolic pathways [18].

| Metabolic Pathway | Insulin's Effect | Key Molecular Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose Metabolism | Stimulates glucose uptake; suppresses hepatic glucose production | Activates phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) pathway; promotes translocation of GLUT-4 transporters to cell membrane in muscle and adipose tissue [18]. |

| Glycogen Metabolism | Promotes glycogenesis (glycogen synthesis) | Activates Protein Phosphatase 1 (PP1), which dephosphorylates and activates glycogen synthase and inactivates glycogen-degrading enzymes [18]. |

| Lipid Metabolism | Stimulates lipogenesis; inhibits lipolysis | Increases expression of lipogenic enzymes (e.g., fatty acid synthase); dephosphorylates and inhibits hormone-sensitive lipase [18]. |

| Protein Metabolism | Stimulates protein synthesis; inhibits degradation | Increases cellular uptake of amino acids; upregulates expression of proteins like albumin and muscle myosin; downregulates proteases involved in degradation [18]. |

The Anti-Inflammatory Role of Insulin

Beyond its metabolic roles, insulin possesses significant anti-inflammatory properties. Within endothelial cells and macrophages, insulin suppresses the activity of the pro-inflammatory transcription factor nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB). This suppression reduces the expression of adhesion molecules and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8. Insulin also stimulates the release of nitric oxide (NO) from the endothelium, promoting vasodilation, and suppresses the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in macrophages [18]. In the context of obesity, the development of insulin resistance (IR) creates a vicious cycle by disrupting these anti-inflammatory actions and promoting a state of chronic, low-grade inflammation [19].

Cellular Pathology of Injection Site Trauma

Repeated insulin injections or infusion set placements can cause localized tissue injury, initiating a wound healing response that, when chronically activated, leads to pathological skin complications. The two most common sequelae are lipohypertrophy and fibrosis [20].

Lipohypertrophy

This condition is characterized by a local accumulation of fatty tissue at the injection site. It results from the direct stimulatory effect of insulin on adipocytes, leading to both hypertrophy and hyperplasia of fat cells [20]. It is incredibly common, with an estimated prevalence of between 14.5% and 88% of insulin-dependent people with diabetes [20].

Fibrosis

Fibrosis involves the accumulation of stiff, dense scar tissue at the injection site. It is a chronic process driven by repeated minor tissue trauma and the ensuing inflammatory response. This leads to the activation of fibroblasts, which deposit a pathological amount of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins [20].

The table below compares these two primary complications.

| Feature | Lipohypertrophy | Fibrosis (Scarring) |

|---|---|---|

| Pathological Process | Local expansion of adipose tissue [20]. | Excessive deposition of dense, collagen-rich scar tissue [20]. |

| Primary Cellular Driver | Adipocytes (fat cells) [20]. | Fibroblasts [20]. |

| Key Stimulus | Direct anabolic effect of insulin on lipid metabolism [20]. | Repeated tissue trauma and inflammatory response [20]. |

| Palpable Feel | Soft, rubbery, or swollen mass [20]. | Firm, hard, dense nodule [20]. |

Insulin-Derived Amyloidosis

A less common but significant complication is insulin-derived amyloidosis (AIns), where insulin aggregates into amyloid fibrils at the injection site, forming palpable, hard subcutaneous masses. The formation of these cytotoxic fibrils, primarily from the insulin B-chain, fundamentally disrupts insulin absorption, leading to subcutaneous insulin resistance and poor glycemic control [21]. A key finding is that the average daily insulin dose can be reduced by 30 units when patients avoid injecting into amyloid sites [21].

The Role of Mechanical Forces and Experimental Pathways

Mechanopathology of Tissue Trauma

The role of mechanical forces in the development of injection site complications is a critical area of research.

- Fibrosis and Mechanical Tension: Fibroblasts are highly sensitive to mechanical stress. Increased skin tension stimulates them to produce excess ECM, a hallmark of fibrosis. Clinical studies have shown that tension-offloading of surgical wounds significantly reduces scarring, suggesting a similar approach could benefit injection-related fibrosis [20].

- Lipohypertrophy and Compression: Adipocytes also sense mechanical forces. Intriguingly, in vitro studies indicate that compressive force can inhibit adipocyte production and differentiation by downregulating key adipogenic genes. This suggests that applying controlled compression might counteract the processes driving lipohypertrophy [20].

Experimental Therapeutic Strategies

A proposed theoretical approach involves using a tension-offloading dressing (e.g., the embrace device) at insulin injection sites. This device applies a compressive, tension-reducing force across the skin. Based on existing evidence, this strategy could simultaneously target the mechanical drivers of both fibrosis (by reducing tension) and lipohypertrophy (by applying compression) [20]. Clinical trials are needed to validate this approach for preventing insulin injection site complications [20].

Mechanistic Pathways of Injection Site Trauma and a Theoretical Intervention

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Methodologies

The following table details essential materials and methods for investigating insulin's molecular biology and injection site pathologies.

| Tool/Reagent | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Ultrasonography | Used to non-invasively measure skin and subcutaneous tissue thickness, identify and characterize lesions like lipohypertrophy and amyloidosis, and guide needle length selection [11] [21]. |

| Tension-Offloading Dressings | An experimental device (e.g., embrace) applied to injection sites to apply compressive, tension-reducing forces; used to test the hypothesis that modulating mechanics prevents fibrosis and lipohypertrophy [20]. |

| Behavioral Insulin Administration Skills (BIAS) Rubric | A validated observational scoring tool used in clinical studies to systematically assess a patient's insulin injection technique and identify common errors [22]. |

| Injection Technique Questionnaire (ITQ) | A large-scale global survey tool used to collect data on patients' injection practices, knowledge, and the prevalence of skin complications [11]. |

| Histological Staining & Analysis | Essential for definitive diagnosis of tissue complications. Allows for visualization of amyloid deposits, fibrotic scar tissue, and adipocyte morphology in biopsy samples [20] [21]. |

| Cell Culture Models (Fibroblasts & Adipocytes) | In vitro systems used to study the direct effects of insulin and mechanical forces (tension/compression) on ECM production, fibroblast activation, and adipocyte differentiation/gene expression [20]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Troubleshooting Experimental & Clinical Challenges

Q1: In our in vitro models, we see inconsistent results when studying insulin's effect on adipogenesis. What is a key mechanical factor we might be overlooking? A: The application of compressive force has been shown in vitro to inhibit adipocyte production and differentiation by down-regulating key adipogenic genes [20]. Standard cell culture methods may not account for this mechanical variable. Ensure your experimental setup controls for or investigates the role of physical force on adipocyte behavior.

Q2: Our clinical trial data shows high variability in insulin absorption rates among participants. What is a common, often overlooked, confounding variable we should control for? A: Injection into lipohypertrophic or fibrotic sites is a major source of erratic absorption. One study found that total daily insulin doses for patients with lipohypertrophy were, on average, 36% higher (an absolute difference of 15 IU/day) than for those without it, due to impaired and variable absorption [20] [22]. Protocol should include systematic palpation and visual inspection of all potential injection sites by a trained clinician to exclude these areas from the study.

Q3: When developing new insulin formulations, how can we pre-clinically assess the risk of inducing localized amyloidosis? A: The formation of amyloid fibrils is linked to the dissociation of insulin hexamers into monomers, with the B-chain being the principal amyloidogenic factor [21]. Pre-clinical assays should focus on the formulation's stability and its propensity for monomer aggregation under stress conditions. Techniques like electron microscopy and thioflavin T staining can be used to detect fibril formation in experimental models.

Q4: What is the most critical technique failure in patients with poorly controlled glucose despite high insulin doses? A: A failure to properly rotate injection sites is a primary cause. Repeated injections in the same spot lead to lipohypertrophy and fibrosis, which severely impair insulin absorption. Educating patients on structured rotation, using methods like a 4x4 grid on the abdomen and moving to different body parts, is crucial [23]. Studies show that simply educating patients on proper rotation can lead to significant improvements in glycemic control and a reduction in daily insulin requirements [11].

The Direct Link Between Lipohypertrophy and Unpredictable Insulin Pharmacokinetics

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the pathophysiological basis for altered insulin absorption in lipohypertrophic tissue?

A1: Lipohypertrophy (LH) is characterized by adipose tissue hyperplasia and hypertrophy, combined with fibrotic tissue deposition [3] [20]. Histological analysis reveals that approximately 75% of the subcutaneous tissue in LH lesions consists of macro-adipocytes that are significantly larger than normal adipocytes, alongside increased fibrosis and apoptosis [3]. This pathological remodeling creates a diffusion barrier and alters local blood flow. The fibrotic component impedes insulin diffusion, while the enlarged, insulin-stimulated adipocytes create an erratic reservoir effect. This combination results in non-linear and unpredictable absorption kinetics, manifesting as both delayed and sometimes accelerated insulin release into the systemic circulation [20] [24].

Q2: What is the prevalence of lipohypertrophy in research cohorts, and what are its primary risk factors?

A2: The prevalence of LH is substantially high but varies significantly with detection methodology. Clinical studies using visual inspection and palpation report prevalence rates between 37% and 64% in insulin-treated populations [3] [9]. When more sensitive ultrasound techniques are employed, detection rates can be even higher, as ultrasound identifies structural changes in deeper tissue layers before surface manifestations occur [3]. The key risk factors identified in clinical research are summarized in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Key Risk Factors for Lipohypertrophy Development

| Risk Factor | Experimental/Observational Evidence |

|---|---|

| Lack of Injection Site Rotation | Consistently identified as the primary modifiable risk factor; leads to concentrated micro-trauma and localized insulin action [3] [9] [25]. |

| Needle Reuse | Damages the needle tip (visible under microscopy), increasing tissue trauma and the risk of scarring and LH [3] [17] [24]. |

| High Number of Daily Injections | A higher frequency of injections per day correlates with an increased prevalence of LH [3]. |

| Large Injection Volumes | Single injections exceeding recommended volumes contribute to localized tissue stress and expansion [3]. |

| Longer/Thicker Needles | The use of longer and thicker needles is associated with a greater risk of developing LH [3]. |

Q3: What quantitative impact does lipohypertrophy have on insulin dosing and glycemic outcomes?

A3: LH has a demonstrable and significant impact on both pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic outcomes. Research indicates that total daily insulin doses for patients with LH are, on average, 36% higher than for those without LH, representing an absolute mean increase of 15 IU/day [20]. This suggests impaired and wasted insulin absorption. Glycemically, this translates to increased glycemic variability, a 2.7 times higher risk of unexplained hypoglycemia, and an increased risk of hyperglycemia and diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) [20]. Case studies document patients with fluctuating blood glucose and unpredictable hypoglycemia resolving after avoiding LH sites, with HbA1c improvements of over 2% [24].

Q4: What are the standard and advanced experimental methods for detecting and quantifying lipohypertrophy in a research setting?

A4: The diagnostic and research methods for LH range from simple clinical techniques to advanced imaging, as outlined in the experimental protocol below.

Table 2: Methodologies for Lipohypertrophy Detection and Characterization

| Method | Protocol Description | Utility and Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Visual Inspection & Palpation | Protocol: Visually assess for raised, swollen areas. Perform a pinching maneuver and deep palpation to detect elastic or firm nodules, even if not visible. Change body positioning to improve detectability [3]. | Utility: Low-cost, clinically feasible. Limitation: Low sensitivity for small or deep lesions; diagnostic accuracy highly dependent on examiner training (trained professionals are 45% better at detecting sub-4cm lesions) [3]. |

| High-Frequency Ultrasound | Protocol: Use a high-frequency linear array transducer. Measure dermal and subcutaneous echo-texture, thickness, and look for structural disorganization, hypoechoic areas (fat), and hyperechoic strands (fibrosis) [3]. | Utility: Gold standard for research. ~30% more sensitive than palpation. Allows objective quantification of tissue changes, including depth and fibrosis [3] [20]. |

| Histological Analysis | Protocol: Tissue biopsy of affected sites, followed by staining (e.g., H&E, Masson's Trichrome for collagen) and analysis via light or scanning electron microscopy [3]. | Utility: Reveals pathophysiological mechanisms: macro-adipocytes, fibrosis, and apoptosis. Limitation: Invasive; not for routine use [3] [20]. |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Lipohypertrophy

Protocol for a Randomized Site-Rotation Intervention Study

Objective: To quantify the effect of a structured injection site rotation protocol on the incidence of new LH and glycemic variability.

Methodology:

- Cohort Recruitment: Recruit insulin-dependent participants with no existing LH, confirmed via baseline ultrasound.

- Randomization & Intervention: Randomize into two groups:

- Intervention Group: Follows a structured, timed site rotation schedule (e.g., consistent morning injections in the thigh, evening injections in the abdomen) with each injection spaced at least one finger-width apart [26] [25] [17]. Use of body maps and tracking apps is mandated.

- Control Group: Receives standard care with general advice to rotate sites.

- Blinding: Outcome assessors (e.g., ultrasound technicians) should be blinded to group allocation.

- Outcome Measures:

- Primary: Incidence of new LH at 6 and 12 months, diagnosed by ultrasound.

- Secondary: Change in HbA1c, Glucose Time-in-Range (TIR), hypoglycemia events, and total daily insulin dose.

Protocol for Assessing Insulin Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics (PK/PD)

Objective: To directly compare the absorption profile and action of insulin injected into healthy versus lipohypertrophic tissue.

Methodology:

- Participant Selection: Recruit participants with clearly demarcated LH areas and adjacent healthy tissue.

- Study Design: Cross-over design where each participant serves as their own control.

- Experimental Procedure: After an overnight fast and standardized basal insulin, administer an identical dose of rapid-acting insulin into both the LH site and a healthy control site on separate study days.

- Data Collection: Measure plasma insulin concentrations and blood glucose levels frequently over the subsequent 6-8 hours. Use euglycemic clamps if possible to precisely quantify glucose infusion rates (GIR).

- PK/PD Analysis: Calculate for both sites:

- T~max~: Time to maximum insulin concentration.

- C~max~: Maximum insulin concentration.

- AUC: Total area under the insulin concentration-time curve.

- GIR~AUC~: Total glucose infused to maintain euglycemia.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the mechanistic pathway from repeated insulin injections to unpredictable pharmacokinetics, integrating the roles of mechanical force and insulin's biological action.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Lipohypertrophy Research

| Research Tool / Reagent | Function in Experimental Context |

|---|---|

| High-Frequency Ultrasound System | The primary non-invasive tool for objective quantification of subcutaneous tissue architecture, thickness, and echogenicity to characterize and monitor LH lesions [3]. |

| Human Insulin (Various Formulations) | To study the differential effects of human vs. analog insulin on adipocyte stimulation and LH development in experimental models [9] [24]. |

| Rapid-Acting Insulin Analog | The standard for PK/PD studies due to its widespread use in pumps and injections; allows for precise measurement of absorption kinetics from different tissue sites [27]. |

| Tension-Offloading Dressings | An investigational device (e.g., embrace) based on the hypothesis that reducing mechanical tension can mitigate injection-induced fibrosis and potentially LH, providing a mechanistic intervention [20]. |

| Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Kits | For precise and frequent measurement of serum/plasma insulin concentrations in PK studies, especially when high doses are involved that require sample dilution [28]. |

| Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) Systems | To collect high-resolution glycemic data (Time-in-Range, variability) as a pharmacodynamic readout of insulin absorption efficiency from LH vs. healthy tissue [3] [27]. |

| Sterile Single-Use Needles (4-6mm) | The research standard to control for the confounding variable of needle reuse, ensuring that tissue trauma is consistent and not exacerbated by a damaged needle tip [3] [17]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions for Researchers

Q1: What is the established clinical link between improper injection site rotation and glycemic variability?

A1: Research demonstrates a direct correlation. A 2018 study found that a poorer insulin injection technique score was negatively correlated with the Mean Amplitude of Glycemic Excursion (MAGE), a key metric for GV. Patients who self-injected had significantly higher MAGE than when injections were performed by a specialist nurse, who ensured proper technique including site rotation [29]. Furthermore, improper rotation leads to lipohypertrophy (LH), which results in erratic and unpredictable insulin absorption, directly driving glycemic fluctuations [30] [31].

Q2: How can a researcher experimentally confirm that lipohypertrophy is causing unexplained hypoglycemia in a study subject?

A2: A focused diagnostic approach is required [32].

- Clinical Examination: First, thoroughly inspect and palpate all potential injection sites (abdomen, thighs, arms) for rubbery or raised lumps [30] [31].

- Intervention: Instruct the subject to strictly avoid injecting into any suspected LH areas for a minimum of six months [33].

- Monitoring: Implement continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) to track hypoglycemic events (Time Below Range, TBR) and glycemic variability (Coefficient of Variation, CV) [34] [35].

- Outcome: A significant reduction in unexplained hypoglycemic events and improved GV after switching to healthy injection sites confirms the diagnosis. Concurrently, you may observe a reduction in total daily insulin requirements, as insulin absorption from healthy tissue is more efficient [31].

Q3: What are the core mechanisms by which scar tissue (lipohypertrophy) increases insulin requirements?

A3: Lipohypertrophy alters the pharmacokinetics of insulin via two primary mechanisms [31]:

- Impaired Absorption: The altered architecture of scarred and fatty tissue disrupts normal vascularization, leading to delayed, erratic, or sometimes trapped insulin absorption.

- Reduced Bioavailability: A portion of the injected insulin may become sequestered within the LH tissue, failing to enter the systemic circulation. This necessitates a higher administered dose to achieve the required therapeutic plasma insulin level. When the injection site is subsequently rotated to healthy tissue, the accumulated insulin can be released, leading to dangerous, unexplained hypoglycemia [33].

Q4: Which quantitative metrics from Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) are most critical for assessing the impact of injection technique in a clinical trial?

A4: Beyond HbA1c, CGM provides dynamic data essential for this assessment. Key metrics include [34] [35]:

- Time in Range (TIR): Percentage of time glucose is between 70-180 mg/dL. A low TIR indicates poor control.

- Time Below Range (TBR): Percentage of time glucose is <70 mg/dL (<54 mg/dL is clinically significant). High TBR indicates hypoglycemia risk.

- Coefficient of Variation (CV): A measure of glycemic variability (standard deviation/mean glucose). A CV ≤ 36% indicates stable glucose, while a higher CV predicts hypoglycemia risk.

- Mean Amplitude of Glycemic Excursion (MAGE): A specific measure of major glucose swings, which has been directly linked to poor injection technique scores [29].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Scenarios

Problem: Unexplained Hypoglycemia in a Study Cohort

- Potential Cause: Undiagnosed lipohypertrophy leading to erratic insulin release; surreptitious insulin use; pancreatic pathology (e.g., insulinoma); adrenal or pituitary insufficiency [32] [31].

- Action Plan:

- Inspect and Palpate all injection sites for LH [30].

- Implement Site Rotation and monitor hypoglycemia frequency [33].

- Conduct a focused lab workup during a hypoglycemic event: measure plasma glucose, insulin, C-peptide, and β-hydroxybutyrate. Inappropriately "normal" or high insulin and C-peptide with low glucose suggest excessive endogenous insulin (e.g., from sulfonylurea use or insulinoma), while suppressed insulin points to other causes [32].

Problem: High Glycemic Variability Despite Optimal HbA1c

- Potential Cause: Improper injection technique, including failure to rotate sites and needle reuse, leading to LH [30] [29].

- Action Plan:

- Audit Injection Technique using a validated skill-assessment scale [29].

- Analyze CGM Data for CV and MAGE. A high CV (>36%) confirms unstable control [34] [35].

- Educate on Site Rotation and proper technique. A study showed that correcting technique alone improved MAGE and overall glycemic control [29].

Problem: Consistently High Insulin Requirements with Poor Response

- Potential Cause: Injecting into lipohypertrophic sites with poor absorption, necessitating dose escalation [31].

- Action Plan:

- Systematically rotate to unaffected sites.

- Monitor and Log insulin doses and corresponding glucose responses.

- Expect a Dose Reduction: After switching to healthy sites, insulin requirements often decrease significantly due to restored absorption efficiency. Carefully monitor for hypoglycemia during this transition period [31].

Table 1: Prevalence of Improper Injection Techniques and Lipohypertrophy (Cross-Sectional Study, n=851) [30]

| Parameter | Type 1 Diabetes (n=298) | Type 2 Diabetes (n=553) |

|---|---|---|

| Performed Site Rotation | 66.8% | 69.4% |

| Needle Reuse (>3 times) | 36.6% | 50.5% |

| Lipohypertrophy Prevalence | 57.0% | 55.5% |

| Mean HbA1c (Uncontrolled, >7%) | 8.8% ± 1.8 | 7.6% ± 6.9 |

Table 2: Impact of Injection Technique on Glycemic Control (Self-Controlled Trial, n=52) [29]

| Glycemic Metric | Patient Self-Injection Period | Specialist Nurse Injection Period | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Amplitude of Glycemic Excursion (MAGE) | Significantly Higher | Significantly Lower | < 0.05 |

| Mean Injection Technique Score (out of 30) | 17.0 ± 4.4 | Optimal (30) | Not Applicable |

| Correlation | IT score negatively correlated with MAGE & HbA1c | < 0.05 |

Table 3: Key CGM Metrics for Assessing Glycemic Control and Variability [34] [35]

| Metric | Definition | Target (Most Adults with Diabetes) |

|---|---|---|

| Time in Range (TIR) | % of time glucose is between 70–180 mg/dL | >70% |

| Time Below Range (TBR) | % of time glucose is below 70 mg/dL | <4% |

| Time Above Range (TAR) | % of time glucose is above 180 mg/dL | <25% |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | (Standard Deviation / Mean Glucose) x 100; measures variability | ≤36% |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Injection Technique and Its Correlation with Glycemic Variability

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the quality of insulin injection technique in study subjects and determine its correlation with short-term glycemic variability using Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM).

Methodology (Based on a published self-controlled trial) [29]:

- Subject Recruitment: Enroll patients with diabetes (Type 1 or 2) who have been on a stable regimen of premixed or basal-bolus insulin for at least three months.

- Study Design: A single-center, cross-sectional, self-controlled design.

- Intervention Phases:

- Phase 1 (Patient Injection - 2 days): Subjects self-inject insulin as per their usual technique.

- Phase 2 (Nurse Injection - 2 days): A specialist nurse administers the same type and dose of insulin using optimal technique.

- Data Collection:

- CGM: A CGM system (e.g., Medtronic CGM) is worn for 96 hours throughout both phases. Data from the second day of each phase is analyzed.

- Injection Technique Assessment: On the last day of Phase 1, two independent nurses assess the subject's technique using a validated 15-item skill scale. Each item is scored from 0-2 (maximum score 30). Key items include:

- Key Outcome Measures:

- Primary: Mean Amplitude of Glycemic Excursion (MAGE) during the patient injection period vs. the nurse injection period.

- Secondary: Correlation between the total injection technique score and MAGE; Correlation between the technique score and HbA1c.

Protocol 2: Investigating the Impact of Lipohypertrophy on Insulin Pharmacokinetics

Objective: To compare the absorption profile and glycemic response of insulin injected into lipohypertrophic (LH) sites versus healthy, rotation-managed control sites.

Methodology:

- Subject Selection: Recruit subjects with confirmed, palpable lipohypertrophy.

- Study Design: Randomized, cross-over study.

- Intervention:

- On two separate study days, subjects receive a standardized dose of fast-acting insulin.

- Day A: Injection into a documented LH site.

- Day B: Injection into a healthy, non-LH site (contralateral side or different anatomical area).

- Data Collection:

- Frequent Plasma Sampling: Measure serum insulin and glucose levels at regular intervals (e.g., every 15-30 minutes) for 4-6 hours post-injection.

- CGM: Use CGM to capture real-time glucose fluctuations and calculate TIR, TBR, and CV for each study day [34].

- Absorption Kinetics: Calculate the area under the curve (AUC) for insulin concentration, time to peak concentration (Cmax), and absorption half-life.

- Key Outcome Measures:

- Differences in insulin AUC and Cmax between LH and healthy sites.

- Differences in glucose AUC and the frequency of hypoglycemic events (TBR) between the two conditions.

- Documented delay in time to peak insulin action from LH sites.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: Pathophysiological pathway of poor injection technique consequences.

Diagram 2: Diagnostic workflow for unexplained hypoglycemia.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials and Tools for Investigating Injection Site Complications

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Research | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) System | Provides high-frequency glucose data to calculate GV metrics (MAGE, TIR, TBR, CV) and assess glycemic control in real-world settings [34] [35]. | Medtronic CGM, Dexcom G6 [29]. |

| Validated Injection Technique Assessment Scale | Standardized tool to quantitatively evaluate and score a subject's adherence to proper injection protocols, allowing for correlation with outcomes [29]. | 15-item skill scale (score 0-30) assessing resuspension, site rotation, needle reuse, etc [29]. |

| High-Frequency Plasma Sampling Assays | To measure insulin pharmacokinetics (absorption rate, Cmax, Tmax, AUC) following injection into LH vs. healthy sites. | ELISA or Chemiluminescence assays for serum insulin. |

| Standardized Lipohypertrophy Palpation Protocol | Ensures consistent and objective identification and documentation of LH lesions across all study subjects. | Defined by size, texture (rubbery vs. hard), and location [30] [31]. |

| Ultrasound Imaging | Provides objective, quantitative measurement of subcutaneous tissue structure and can precisely characterize the size and depth of LH lesions. | High-frequency linear array probe. |

Economic and Quality of Life Burden on Patients and Healthcare Systems

Lipohypertrophy (LH), the most prevalent local complication of insulin therapy, presents as subcutaneous nodular swelling due to adipose tissue proliferation at injection sites. With an average occurrence rate of 41.8% among insulin users, LH represents a significant clinical and economic challenge in diabetes management. Insulin injection into LH-affected sites significantly impairs insulin absorption, leading to marked glycemic excursions including both hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia. These clinical consequences contribute to increased healthcare expenditures and represent a substantial quality of life burden for patients. This technical support document establishes a framework for researchers investigating injection site rotation protocols and their impact on preventing LH, thereby reducing the associated economic and quality of life burdens on patients and healthcare systems.

Key Research Gaps and Clinical Challenges

Quantitative Data on LH Prevalence and Risk Factors

Table 1: Epidemiological Data on Lipohypertrophy in Insulin-Treated Diabetes

| Parameter | Statistical Value | Context & Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Global Diabetes Prevalence | 537 million adults (20-79 years) | Represents 10.5% of global population; establishes population at risk [2] |

| China Diabetes Prevalence | 12.4% (over 140 million affected) | Exceeds global rates; highlights significant at-risk population [2] |

| LH Prevalence Average | 41.8% of insulin users | Indicates high frequency of this complication among insulin-dependent patients [2] |

| Common Insulin Regimen | 4 times per day (in studied cohort) | High injection frequency increases LH risk without proper site rotation [2] |

| Mean Insulin Therapy Duration | 7.2 ± 3.2 years (in studied cohort) | Longer therapy duration correlates with increased LH development risk [2] |

Identified Barriers to Effective Injection Site Rotation

Table 2: Barriers to LH Prevention in Diabetes Self-Management

| Theme Category | Specific Barriers | Representative Participant Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Deficits | Insufficient health education, Forgetfulness, Misconceptions | "When I was hospitalized before, they (HCPs) did not tell me about LH..." (P7) [2] |

| Implementation Challenges | Limitations in site rotation, Financial pressures in needle replacement, Failure to self-monitor flat LH | "The HCPs asked me to rotate the injection site, but they did not say how to do it clearly." (P10) [2] |

| Motivational Barriers | Low perceived severity, Low perceived susceptibility | No specific quotation provided in search results, but identified as key thematic barrier [2] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Qualitative Research Protocol for Barrier Identification

Research Design: Qualitative descriptive design using semi-structured interviews [2] Participant Selection:

- Inclusion Criteria: Diagnosis of diabetes mellitus receiving insulin therapy; LH confirmed by ultrasound examination; self-administered insulin at home prior to admission; volunteered for study participation [2]

- Exclusion Criteria: Medical record of severe psychiatric or cognitive disorders; inability to participate in interviews for any reason [2] Sample Characteristics: 17 participants (10 male, 7 female) with type 2 diabetes; mean age 56.1±8.3 years [2] Data Collection: Face-to-face interviews in quiet, separate room; 20-60 minute duration; audio recorded and transcribed verbatim within 24 hours; participants reviewed summaries for factual verification [2] Data Analysis: Thematic analysis following Braun and Clarke methodology; six-phase analytical process using NVivo 8 software; continued until data saturation achieved [2]

Ultrasound Detection Protocol for LH Assessment

Clinical Procedure: Ultrasound examination emerges as superior diagnostic modality compared to conventional palpation, offering enhanced sensitivity and specificity particularly for non-palpable LH [2] Technical Advantages: Facilitates precise identification of optimal injection sites in patients with LH concerns; enables detection of flat LH lesions that are challenging to identify through physical assessment alone [2] Implementation Gap: Lack of routine LH examinations for outpatient and hospitalized individuals with diabetes in hospitals in China highlights translational challenge between research and clinical practice [2]

Diagram 1: Qualitative Research Methodology Workflow for LH Barrier Identification

Technical Support: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions for Research Implementation

Q: What are the most significant methodological challenges in LH prevention research? A: The primary challenges include: (1) accurate detection of non-palpable "flat LH" without routine ultrasound screening; (2) participant adherence to complex site rotation protocols in real-world settings; (3) differentiation between knowledge deficits and implementation barriers; and (4) accounting for financial constraints that lead to needle reuse exceeding recommended limits [2].

Q: How can researchers effectively measure adherence to injection site rotation protocols? A: Recommended approaches include: (1) combining self-report interviews with visual inspection and ultrasound confirmation; (2) utilizing injection site mapping tools to track rotation patterns; (3) assessing needle reuse through prescription refill patterns and direct participant reporting; and (4) incorporating both qualitative and quantitative measures to capture the multifactorial nature of adherence barriers [2].

Q: What physiological mechanisms explain impaired insulin absorption at LH sites? A: While the complete mechanism requires further research, current evidence suggests that injection into LH-affected areas significantly alters insulin pharmacokinetics, resulting in impaired absorption and marked glycemic excursions. The anabolic effects of insulin on regional adipose tissue, combined with repeated injection-induced subcutaneous tissue trauma and subsequent repair processes, contribute to this phenomenon [2].

Q: How do financial barriers impact needle replacement practices? A: Economic constraints create significant pressure for patients to reuse needles beyond recommended limits. This cost-saving measure directly contradicts optimal injection technique guidelines which recommend single-use disposable needles, creating a tension between clinical recommendations and financial realities for many patients [2].

Troubleshooting Guide for LH Research Protocols

Problem: Low participant recognition of flat LH lesions during self-assessment. Solution: Implement standardized ultrasound screening protocols at study baseline to establish objective LH presence regardless of palpability. Develop visual aids and tactile training tools to enhance participant detection capabilities [2].

Problem: Inconsistent application of site rotation protocols among study participants. Solution: Utilize simplified rotation guides with clear visual mapping of appropriate sites (abdominal wall, lateral/posterior arms, anterolateral thighs, and buttocks). Emphasize the critical ≥1 cm spacing requirement between injections through practical demonstration and reinforcement [2].

Problem: High rates of needle reuse contradicting research protocols. Solution: Acknowledge financial pressures and incorporate needle provision into study design where feasible. Address cost-benefit perceptions through education about long-term consequences of LH development, including increased insulin requirements and healthcare utilization [2].

Problem: Underestimation of LH severity and susceptibility among participants. Solution: Develop targeted educational materials demonstrating the clinical and economic impact of LH, including its effects on glycemic control, insulin pharmacokinetics, and long-term diabetes outcomes [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Methodologies for LH Research

| Research Tool | Specifications & Applications | Research Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound Imaging System | High-frequency linear array transducer (7-15 MHz) | Gold-standard detection of LH lesions, particularly non-palpable "flat LH"; enables precise characterization of subcutaneous tissue changes [2] |

| Semi-structured Interview Guide | Open-ended questions exploring knowledge, practices, and barriers | Qualitative data collection on patient experiences, perceptions, and implementation challenges regarding injection site rotation [2] |

| Site Rotation Mapping Tool | Anatomical diagrams with injection site documentation | Visual documentation of rotation practices; enables correlation of specific sites with LH development patterns [2] |

| Needle Use Assessment Protocol | Combination of self-report and prescription refill data | Objective measurement of needle replacement practices and identification of economic barriers to adherence [2] |

| Qualitative Data Analysis Software | NVivo, MAXQDA, or similar platforms | Systematic organization and thematic analysis of interview transcripts; facilitates identification of emergent themes and patterns [2] |

Diagram 2: Clinical Consequences Pathway of Lipohypertrophy Development

The economic and quality of life burden associated with lipohypertrophy represents a significant yet preventable challenge in diabetes management. The identified barriers—knowledge deficits, implementation challenges, and motivational factors—provide critical targets for intervention development. Future research should focus on translating these findings into practical, patient-centered solutions that address both the clinical and economic dimensions of LH prevention. By developing more effective injection site rotation protocols and addressing the systemic barriers to their implementation, researchers can contribute substantially to reducing the economic and quality of life burden on both patients and healthcare systems.

Evidence-Based Protocols for Optimal Injection Technique and Site Rotation

FAQs: Core Principles of the FITTER Forward Guidelines

Q1: What are the FITTER Forward recommendations and why were they developed?

Q2: How do proper injection techniques specifically prevent lipodystrophy in research models?

Lipodystrophy, particularly lipohypertrophy (LH), is a common complication of subcutaneous insulin injections, presenting as thickened, "rubbery" tissue swellings [37]. The pathophysiology involves both the growth-promoting properties of insulin and localized trauma from poor injection habits. Injecting into these lesions causes erratic insulin absorption, leading to wide glycemic oscillations including unexplained hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, which are scarcely responsive to insulin dose adjustments [37]. Proper site rotation prevents this localized trauma. The FITTER Forward guidelines emphasize that correct technique is a more crucial factor in maintaining target blood glucose levels than many realize, directly impacting the predictability of insulin absorption and the prevention of LH [38].

Q3: What are the critical methodological steps for assessing injection sites in clinical research?

A key diagnostic methodology involves systematic palpation of all potential injection sites [37]. Researchers should visually inspect and palpate for areas that feel lumpy, firm, rubbery, or raised compared to surrounding tissue [9]. These areas often have reduced sensation. In research settings, accurate identification is crucial as LH can be easily missed in a standard examination. The use of ultrasound and radiological methods can provide objective confirmation, but structured palpation techniques have been validated for clinical and research identification of LH [37]. Unexplained variations in glucose levels and/or unexplained hypoglycemic episodes in study participants should prompt a thorough examination for LH [37].

Q4: What are the quantitative clinical impacts of improper injection technique?

Improper technique, particularly injection into lipohypertrophic tissue, has significant, measurable clinical consequences. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from the literature.

Table 1: Quantitative Impacts of Improper Injection Technique and Lipohypertrophy (LH)

| Parameter | Impact | Source/Study Context |

|---|---|---|

| LH Prevalence | Affects up to 64% of people with diabetes; 46.2% in a study of 780 insulin-treated adults [37]. | Clinical observational studies [9] [37]. |

| Glycemic Control | Erratic absorption causes wide glucose oscillations, increased hypoglycemia, and hyperglycemia [9] [37]. | Clinical observation in patients with LH [9] [37]. |

| Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) | Can be reduced by 1.0% within 6 months by correcting technique errors like needle reuse and using proper needle length [39]. | Interventional study on injection technique [39]. |

| Insulin Dose | Increased requirements are common when injecting into LH sites; doses often normalize after switching to healthy sites [9] [37]. | Clinical observation [9] [37]. |

| Needle Reuse | 39% of participants in a Canadian survey reused pen needles, a major risk factor for LH [39]. | Survey of 230 Canadian participants [39]. |

| Injection into LH | 37% of survey participants injected insulin into lipohypertrophic tissue [39]. | Survey of 230 Canadian participants [39]. |

Troubleshooting Guides for Research and Clinical Practice

Guide 1: Managing and Reversing Lipohypertrophy in Study Cohorts

Problem: Persistent lipohypertrophy (LH) nodules in clinical trial participants, leading to unpredictable insulin pharmacokinetics and compromised study data.

Solution Protocol:

- Immediate Cessation: Instruct participants to completely avoid injecting into any identified LH areas. This is the single most critical step [9].

- Healing Period: Document a cessation period of a minimum of 2 to 3 months, and sometimes years, for the tissue to heal and return to normal [9] [23].

- Site Mapping: Implement a structured site rotation plan for the participant using a body map or chart to track used and unused sites, ensuring healed areas are not re-used prematurely [9] [17].

- Verification: Confirm tissue healing via palpation (and ultrasound if available) before the area is cleared for use again in the study [9] [37].

- Surgical Consideration (Severe Cases): For severe, persistent deposits that do not resolve with conservative management, a protocol deviation may be considered for surgical removal via liposuction [9].

Guide 2: Implementing a Structured Rotation Protocol

Problem: Inconsistent and inadequate site rotation, a primary cause of lipodystrophy.

Solution Protocol: Adopt the FITTER Forward-recommended structured rotation plan [40] [38], which can be visualized as the following workflow for research participants.

Key Procedural Steps:

- Site Selection: Valid regions include the abdomen (avoiding a 5 cm perimeter around the navel), thighs, buttocks, and upper arms [17] [23].

- Systematic Rotation: Within a region (e.g., abdomen), use a systematic pattern, moving injection sites at least 1-2 cm (one finger width) apart from the previous injection [9] [39]. For pump infusion sets, the minimum distance is 1 inch for 90-degree sets and 2 inches for angled sets [23].

- Needle Usage: Mandate the use of a new needle for every injection to prevent tissue trauma and ensure sterility [9] [39] [17].

- Documentation: Provide participants with a logbook, calendar, or smartphone app to meticulously track injection sites [9] [23].

Guide 3: Addressing Participant-Specific Barriers to Adherence

Problem: Low adherence to rotation protocols due to participant-reported barriers.

Solution Protocol: A survey of youth with Type 1 diabetes identified key barriers and offers targeted solutions [41].

Table 2: Common Barriers to Site Rotation and Proposed Mitigation Strategies

| Barrier | Proposed Mitigation Strategy for Researchers |

|---|---|

| Fear of Pain in New Sites [41] | Counsel on using room-temperature insulin and shorter needles (4-6 mm). Teach relaxation and distraction techniques. [41] [17] |

| Difficulty Reaching Sites (e.g., arms, buttocks) | Recommend the use of an insertion device for hard-to-reach sites. For self-injection, identify the most accessible body regions for the participant. [23] |

| Habit and Forgetfulness | Implement structured reminder systems: pump alarms, phone alerts, or calendar notations. Correlate site changes with a regular weekly activity. [23] |

| Belief that LH is Not Problematic | Educate on the direct link between LH, erratic insulin absorption, and unexplained hypoglycemia/hyperglycemia, using data from Table 1. [9] [37] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Materials

This table details essential materials for studies investigating injection techniques and lipodystrophy.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Injection Technique Studies

| Item | Function/Justification in Research |

|---|---|

| Short Pen Needles (4-6 mm) | Recommended for most adults to ensure subcutaneous delivery and minimize intramuscular injection, a key variable in pharmacokinetic studies. [39] [17] |

| Non-Posted (Contoured) Pen Needles | Research tool to control for and study the impact of unintended injection force, which can lead to intramuscular injection and variable results. [39] |

| High-Frequency Ultrasound System | Gold-standard for objective, quantitative measurement of subcutaneous fat thickness and the precise characterization of lipohypertrophic lesions. [37] |

| Structured Palpation Protocol | A validated, low-cost methodological tool for the systematic identification and documentation of lipohypertrophic skin lesions during clinical assessments. [37] |

| Patient Body Maps & Logbooks | Essential for tracking injection site history, correlating specific sites with local tissue reactions, and monitoring adherence to rotation protocols. [9] [23] |

Visualizing the Pathophysiology and Clinical Impact

The following diagram synthesizes the relationship between improper injection practices, the development of lipohypertrophy, and the subsequent clinical and research outcomes, as detailed in the literature [9] [39] [37].

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

What is injection site lipodystrophy and why should researchers be concerned about it?

Lipodystrophy (LD) is a disorder of adipose tissue and a common complication of subcutaneous insulin injections in research models. It presents in two primary forms [37]:

- Lipoatrophy (LA): Defined as large, often deep, retracted scars on the skin resulting from serious damage to subcutaneous fatty tissue. Its prevalence has dropped to only 1–2% with the use of purified insulin, and an immunological etiology is suggested [37].

- Lipohypertrophy (LH): Characterized by thickened, "rubbery" tissue swellings which may be firm or occasionally soft. The exact etiology is unclear but is associated with the insulin molecule's growth-promoting properties and repeated trauma from poor injection habits like infrequent site rotation and needle reuse [37].

Clinical/Experimental Consequences: Injecting into LD-affected sites causes wide glycemic oscillations, including inexplicably high glucose levels and unexplained hypoglycemic episodes. These fluctuations are poorly responsive to insulin dose adjustments and can compromise data integrity in studies involving insulin administration [37].

How can researchers systematically define anatomical rotation zones to prevent lipodystrophy?

A systematic approach involves dividing the body into standardized anatomical zones based on established terminology [42] [43] [44].

- Anterior and Posterior Trunk: Utilize the ventral (anterior) and dorsal (posterior) surfaces. The abdomen is a common injection site on the anterior trunk [43].

- Lateral Aspects of Trunk and Limbs: The lateral body surfaces, away from the midline, provide additional injection areas [43].

- Proximal and Distal Limb Segments: The limbs can be divided into proximal segments (closer to the torso, like the upper arm and thigh) and distal segments (further away, like the forearm) [43].

- Consistent Landmarks: Use fixed bony landmarks, such as the iliac crest or patella, to ensure consistent and reproducible zone delineation across multiple researchers and sessions [43].

What are the best practices for implementing a rotation scheme in a longitudinal study?

Implementing a successful rotation scheme requires planning and documentation.

- Structured Patterns: Employ fixed, predictable rotation patterns (e.g., Zone A → Zone B → Zone C) to ensure all sites are used equally and allow adequate time for tissue recovery between injections in the same zone [45].

- Detailed Documentation: Meticulously log the specific zone used for each injection for every subject. Visual aids and maps in animal records can enhance accuracy [37].

- Regular Palpation: Before each injection, palpate (feel) the intended site for any rubbery or thickened tissue (indicating LH) or retracted areas (indicating LA). Avoid injecting into these areas [37].

Troubleshooting: If subjects exhibit unexplained glycemic variability, check for undiagnosed LH at common injection sites. Implementing an educational program on proper rotation techniques has been shown to significantly reduce glucose oscillations [37].

What quantitative data supports the need for systematic site rotation?

The table below summarizes key findings from clinical studies on lipodystrophy prevalence and its impact [37].

| Parameter | Quantitative Finding | Study Context |

|---|---|---|

| LH Prevalence | 46.2% of patients | n=780 insulin-treated adults (Type 1 & 2) |

| Mean LH Lesion Diameter | 4.8 ± 3.1 cm | n=780 insulin-treated adults (Type 1 & 2) |

| LA Prevalence | 3.2% of patients | n=780 insulin-treated adults (Type 1 & 2) |

| Bruising Prevalence | 33.2% of patients | n=780 insulin-treated adults (Type 1 & 2) |

| Effect of Education | Significant reduction in glucose oscillations | Observed after patient education on injection technique |

Experimental Protocols for Monitoring Lipodystrophy

Protocol 1: Palpation and Visual Inspection for Lipohypertrophy and Lipoatrophy

Objective: To consistently identify and document LD in research subjects. Materials: Examination gloves, subject skin maps, calipers (for measuring lesion size), camera (for documentation). Methodology [37]:

- With the subject in a relaxed, standing or sitting position, expose the common injection sites (abdomen, thighs, upper arms).

- Visually inspect all sites for visible swellings, dimples, or skin retractions.

- Using the palmar surfaces of the fingers, systematically palpate all injection zones.

- Feel for abnormal tissue consistency—LH typically presents as a thickened, "rubbery" swelling, while LA feels like an indentation or loss of underlying tissue.

- If a lesion is found, measure its dimensions with calipers and document its location and characteristics on the subject's skin map. Photograph the lesion if possible for longitudinal tracking. Frequency: This inspection should be performed weekly during studies involving frequent subcutaneous injections.

Protocol 2: Ultrasound Assessment of Subcutaneous Tissue Thickness

Objective: To obtain quantitative, high-fidelity data on subcutaneous tissue changes. Materials: High-frequency linear array ultrasound system, ultrasound gel, measurement calipers (digital). Methodology [37]:

- Mark standard anatomical zones on the subject's skin with a surgical pen for consistent probe placement over time.

- Apply ultrasound gel to the transducer head to ensure acoustic coupling.

- Place the transducer perpendicular to the skin surface on the marked zone. Acquire a clear image showing the skin layer, subcutaneous tissue (hypodermis), and underlying muscle fascia.

- Use the machine's electronic calipers to measure the distance from the dermis-subcutaneous junction to the subcutaneous-muscle fascia junction.