Model Predictive Control vs. Standard Insulin Therapy: A Comprehensive Validation for the Artificial Pancreas

This article provides a systematic analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the validation of Model Predictive Control (MPC) for automated insulin delivery against standard insulin therapy.

Model Predictive Control vs. Standard Insulin Therapy: A Comprehensive Validation for the Artificial Pancreas

Abstract

This article provides a systematic analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the validation of Model Predictive Control (MPC) for automated insulin delivery against standard insulin therapy. It covers the foundational principles of MPC and its advantages over traditional reactive control, explores methodological approaches including model personalization and data-driven predictors, addresses key optimization challenges and limitations of current hybrid systems, and synthesizes clinical evidence from meta-analyses and trials. The review highlights how MPC-based systems significantly improve time-in-range and reduce hypoglycemia, while outlining future research directions for next-generation, fully automated insulin delivery.

Understanding Model Predictive Control and Its Role in Diabetes Technology

Core Principles of Model Predictive Control (MPC) for Insulin Delivery

Model Predictive Control (MPC) has emerged as a leading control strategy for developing Automated Insulin Delivery (AID) systems, also known as the artificial pancreas, for managing type 1 diabetes [1] [2]. This advanced control methodology utilizes mathematical models of glucose-insulin interactions to forecast future glucose levels and autonomously calculate optimal insulin doses [1]. By continuously modulating subcutaneous insulin delivery in response to real-time sensor glucose concentrations, MPC-based systems aim to maintain blood glucose within a target range while minimizing hypoglycemia risk [3]. The evolution of AID systems represents a significant technological breakthrough, enabling people with type 1 diabetes to achieve better glycemic outcomes and improved quality of life [4] [5]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of MPC-based insulin delivery performance against standard therapies, detailing experimental protocols and technical implementations for research applications.

Core Algorithmic Framework and Variants

Fundamental MPC Architecture

The fundamental MPC architecture for insulin delivery operates as a receding horizon optimal controller. The algorithm employs an internal model of glucose-insulin dynamics to predict future glucose trajectories over a predefined prediction horizon (typically 2-4 hours) based on current glucose readings, insulin delivery history, and announced meals [1]. At each control cycle (usually every 5-15 minutes), it computes an optimal sequence of insulin infusion rates that minimizes deviation from the target glucose range while respecting safety constraints on maximum insulin delivery and hypoglycemia risk [1] [2]. Only the first insulin command in this sequence is implemented, and the optimization repeats at the next control interval with updated glucose measurements.

Key mathematical components include:

- State-Space Model: A linearized representation of glucose-insulin-physiology dynamics

- Cost Function: Quadratic programming formulation penalizing glucose deviations from target

- Constraints: Safety limits on insulin infusion rates, insulin-on-board, and glucose thresholds

- State Estimator: Kalman filter or similar approach to handle sensor noise and unmeasured disturbances

Advanced MPC Formulations

Recent research has developed specialized MPC variants to address specific challenges in glycemic control:

Offset-Free Zone MPC (OF-ZMPC) incorporates disturbance estimation techniques to correct plant-model mismatch, ensuring accurate insulin dosing despite physiological variations [1] [2]. This approach eliminates steady-state errors that occur with traditional MPC when actual patient response differs from model predictions.

Impulsive MPC delivers insulin as discrete impulses rather than continuous infusions, better aligning with the physiological need for bolus insulin responses to meals and correcting hyperglycemic excursions [6] [1]. This formulation is particularly effective for handling sudden glucose rises from unannounced carbohydrate intake.

Adaptive Personalized MPC automatically adjusts control parameters based on recent individual patient data, dynamically modulating control aggressiveness according to temporal patterns in insulin sensitivity [1] [2].

Multi-Hormonal MPC extends beyond insulin-only control to incorporate glucagon delivery in dual-hormone systems, providing an additional counter-regulatory mechanism to prevent hypoglycemia, especially during exercise and overnight periods [5].

Comparative Efficacy Analysis: MPC vs. Standard Therapies

Glycemic Outcomes in Type 1 Diabetes

Table 1: Comparison of Glycemic Outcomes for AID Systems Using MPC vs. Standard Insulin Therapy in Type 1 Diabetes

| Treatment Modality | Time in Range (70-180 mg/dL) | Time Above Range (>180 mg/dL) | Time Below Range (<70 mg/dL) | Evidence Certainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced Hybrid Closed-Loop (AHCL) | +24.1% [18.2%; 29.9%] | -19.6% [-25.1%; -14.0%] | No significant difference | Moderate [4] [7] |

| Hybrid Closed-Loop (HCL) | +19.7% [13.2%; 26.1%] | Data not reported | No significant difference | Moderate [4] [7] |

| Full Closed-Loop (FCL) | +25.5% [11.1%; 39.9%] | Data not reported | No significant difference | High [4] [7] |

| Sensor-Augmented Pump (SAP) | Reference | Reference | Reference | [7] |

The network meta-analysis of 46 randomized controlled trials with 4,113 participants demonstrates that MPC-driven AID systems significantly improve time in range compared with pump therapy alone [4] [7]. The benefits are consistent across different AID architectures, with advanced systems showing incremental improvements.

Special Population Applications

Table 2: MPC Performance in Special Populations and Challenging Conditions

| Population/Condition | Key Findings | Study Design |

|---|---|---|

| Type 2 Diabetes Requiring Dialysis | TIR (5.6-10.0 mmol/L): 52.8% (closed-loop) vs. 37.7% (control); P<0.001 [3] | 20-day randomized crossover trial (n=26) |

| Overnight Control in Adults | Overnight TIR (3.9-8.0 mmol/L): +13.5% with closed-loop (p<0.001) [8] | 4-week multicenter crossover study (n=24) |

| Unannounced Meal Challenge (Preclinical) | 83.4% TIR (80-180 mg/dL) with peak hyperglycemia regulated within 50 minutes [6] [1] | 72-hour test in diabetic rats (n=14) |

| Exercise Management | Reduced hypoglycemia with elevated temp targets; automatic detection in development [5] | Multiple outpatient RCTs |

MPC-based systems have demonstrated efficacy in challenging clinical scenarios, including patients with end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis, where glucose management is particularly difficult due to altered glucose metabolism [3]. These systems automatically adjust insulin delivery on dialysis days versus non-dialysis days, responding to changing insulin sensitivity [3].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Clinical Trial Designs

Outpatient Randomized Controlled Trials The strongest evidence for MPC efficacy comes from outpatient randomized controlled trials with intervention periods of at least three weeks [4] [7]. These studies typically employ crossover designs where participants complete both experimental (MPC) and control (standard therapy) periods in random order, separated by washout periods [8] [3]. Studies utilize intention-to-treat analysis, with primary endpoints focused on continuous glucose monitoring metrics, particularly time in target range (70-180 mg/dL) [4] [7].

Transitional Study Designs Initial feasibility studies often begin with supervised clinical research facility admissions [8], followed by transitional designs with the first night of closed-loop supervised in-hospital and subsequent nights unsupervised at home [8]. This approach allows safety monitoring during algorithm familiarization while collecting real-world efficacy data.

Blinding and Control Considerations While complete blinding is challenging due to visible devices, control groups typically use sensor-augmented pump therapy with or without predictive low glucose suspend features [8] [7]. Recent trials have improved blinding by using masked continuous glucose monitors during control periods [3].

Preclinical Validation Models

Diabetic Rat Models Preclinical validation of novel MPC algorithms utilizes diabetic rodent models induced with streptozotocin [6] [1]. A typical protocol involves: (1) diabetes induction and recovery; (2) Day 1: manual insulin injection with glucose response recording and offline parameter estimation; (3) Day 2: controller parameter testing and adjustment; (4) Day 3: initiation of 72-hour fully autonomous operation with unannounced meals [6] [1]. These models demonstrate the controller's ability to handle plant-model mismatch, with reported median absolute relative difference between predictions and actual sensor data of 24.66% [6].

In-Silico Simulation The FDA-accepted UVA/Padova type 1 diabetes simulator provides a robust in-silico environment for preliminary algorithm testing [1] [2]. This approach allows researchers to test control strategies across virtual populations with different ages, insulin sensitivities, and meal challenges before proceeding to animal or human trials [1].

Technical Implementation and Research Toolkit

Essential Research Components

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for MPC Insulin Delivery Development

| Component | Specifications | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitor | Freestyle Libre (Abbott) with Miaomiao transmitter; 5-minute sampling [1] | Real-time glucose sensing for control algorithm |

| Insulin Pump | Custom ESP32-based pump with DRV8833 motor driver; precision dosing [1] | Accurate subcutaneous insulin delivery |

| Control Algorithm | Offset-free zone MPC with impulsive capabilities [6] [1] | Core optimization and decision engine |

| Rapid-Acting Insulin | Faster insulin aspart (FiAsp) [3] | Reduced pharmacodynamic delay for better postprandial control |

| Communication Framework | Bluetooth/WiFi connectivity with safety interlock [1] | Reliable data exchange between system components |

| Physical Activity Monitor | Consumer wearables (smartwatches/rings) with heart rate and accelerometry [5] | Exercise detection for hypoglycemia prevention |

System Architecture and Workflow

The system architecture illustrates the continuous feedback loop essential for MPC operation. The controller integrates real-time glucose data with physiological models to compute optimal insulin dosing decisions while incorporating physical activity signals for enhanced hypoglycemia prevention [5] [1].

Current Research Gaps and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, several research challenges remain in MPC development for insulin delivery:

Meal and Exercise Detection Current AID systems are predominantly hybrid, requiring manual announcement of carbohydrate intake and exercise [5]. Next-generation systems are focusing on automated meal and exercise detection using pattern recognition algorithms integrated with wearable device data [5]. Research shows promising approaches including simplified meal announcements (qualitative estimates rather than precise counting), gesture detection apps that recognize eating behaviors, and integration of meal composition models that account for fat and protein effects on postprandial glucose [5].

Special Populations MPC algorithms require further development and validation in special populations including older adults, pregnant people, and very young children [5]. Current systems are not specifically designed for the unique physiological needs of these groups, representing a significant implementation gap.

Faster-Acting Insulins and Adjunctive Therapies The inherent delays in subcutaneous insulin absorption limit MPC performance, particularly for postprandial control [5]. Research is exploring ultra-rapid insulin formulations and adjunctive therapies like pramlintide (amylin analog) and SGLT2 inhibitors to improve postprandial outcomes [5].

Adaptive Personalization While current systems incorporate some personalization through baseline parameters, future MPC developments focus on continuous adaptation to individual physiological changes, leveraging artificial intelligence and digital twin technologies to create highly personalized models that evolve with the patient's changing metabolism [5] [1].

Model Predictive Control represents the most advanced approach for automated insulin delivery in diabetes management, demonstrating significant improvements in time-in-range across diverse patient populations compared to standard insulin therapies. The core strength of MPC lies in its predictive capabilities and constraint-handling framework, which enable proactive rather than reactive glucose management. As research addresses current challenges in meal detection, exercise response, and population-specific customization, MPC-based systems are poised to deliver increasingly automated and personalized diabetes care. The continued refinement of control algorithms, coupled with advances in insulin formulations and sensor technologies, promises to further reduce the management burden while improving glycemic outcomes for people with diabetes.

For individuals with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), achieving optimal glycemic control is fundamental to preventing long-term complications. Intensive insulin therapy, delivered via multiple daily injections (MDI) or continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) pumps, has been the standard of care. A significant advancement was the introduction of sensor-augmented pump (SAP) therapy, which integrates a CSII pump with a real-time continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) system, allowing users to see trend arrows and current glucose levels. While superior to conventional CSII, SAP therapy still places the burden of decision-making and corrective action entirely on the user. Despite these technological improvements, conventional CSII and SAP therapies exhibit significant limitations, including persistent hyperglycemia, the inescapable risk of hypoglycemia, and substantial user burden, which prevent a large proportion of patients from consistently achieving international glycemic targets. This analysis details these limitations and frames them within the emerging paradigm of model predictive control (MPC), an advanced control strategy that forecasts future glucose levels to automate insulin dosing, thereby directly addressing the core shortcomings of conventional approaches.

Limitations of Conventional Insulin Pump Therapies

Evidence from clinical and real-world studies consistently highlights specific glycemic and usability challenges associated with conventional CSII and SAP therapy.

Glycemic Control Gaps: Persistent Hyperglycemia and Unmet Targets

A primary limitation of conventional CSII and SAP is their inability to reliably eliminate hyperglycemia. A 2018 study examining the switch from CSII to SAP in Japanese patients with T1DM found that while hypoglycemia decreased, the duration of hyperglycemia (>180 mg/dL) did not differ significantly before and after the treatment switch [9]. This indicates that SAP therapy, while beneficial for hypoglycemia, may not be sufficient to fully address elevated glucose levels without more automated intervention.

Long-term data from public healthcare systems corroborate this finding. A 2021 Spanish study of adults with T1DM on CSII for over a decade showed that glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) remained unchanged at 7.5% (58 mmol/mol) from initiation to the end of follow-up [10]. This suggests that the metabolic benefit of CSII may plateau over time, failing to further improve glycemic control despite its use. Furthermore, a 2025 real-world study evaluating automated insulin delivery (AID) systems revealed that at baseline, before switching to an AID, the vast majority of patients using advanced technologies like SAP were not meeting consensus targets; only 9.72% of participants achieved the international goals for Time in Range (TIR), Time Above Range (TAR), and Time Below Range (TBR) [11].

Table 1: Limitations of Conventional CSII and SAP Therapy from Clinical Studies

| Study (Year) | Therapy Analyzed | Key Findings on Limitations | Clinical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ogawa et al. (2018) [9] | SAP vs. conventional CSII | Duration of hyperglycemia (>180 mg/dL) showed no improvement. | SAP does not automatically correct for high glucose levels. |

| Moreno-Fernandez et al. (2021) [10] | Long-term CSII | HbA1c remained at 7.5% over a mean of 11.4 years. | Glycemic benefits of CSII may not improve beyond a certain plateau. |

| Fernandez et al. (2025) [11] | Pre-AID baseline (incl. SAP) | Only 9.72% of patients met all international TIR, TAR, and TBR targets. | Conventional advanced therapies are insufficient for most to achieve goals. |

The Hypoglycemia Problem and Its Impact

Reducing hypoglycemia is a key strength of SAP therapy; however, risks remain. The same Japanese study confirmed that SAP significantly reduced the duration of hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL) at 6 and 12 months [9]. This benefit is not universally observed in all metrics, as the long-term Spanish CSII study reported that the percentage of patients with at least one episode of severe hypoglycemia in the last year decreased from 36% to 7% over the follow-up period [10]. While this represents a major improvement, the persistence of any severe hypoglycemic events underscores a critical limitation of conventional systems: they cannot autonomously suspend insulin delivery to prevent impending hypoglycemia. This inherent risk contributes to psychological burden and fear, which in turn can lead to deliberate chronic hyperglycemia as a protective mechanism by patients.

User Burden and the Challenge of Manual Control

Both conventional CSII and SAP therapies are categorized as "open-loop" systems. The pump delivers insulin based on settings programmed by the user and clinician, but it cannot automatically adjust to dynamic physiological changes. A SAP provides more data, but the onus is still on the user to interpret CGM trend arrows, calculate corrective boluses, and suspend insulin delivery [9]. This constant need for vigilance and manual intervention creates a significant cognitive and behavioral burden, leading to burnout, suboptimal device use, and disengagement from therapy. The limitation is not in the hardware but in the control logic; these systems lack the predictive and automated decision-making capabilities required for truly responsive insulin dosing.

Model Predictive Control: A Theoretical Framework for Overcoming Limitations

Model predictive control (MPC) is an advanced method of process control that uses an internal dynamic model to forecast future system behavior. In the context of diabetes, an MPC algorithm uses mathematical models of a patient's glucose-insulin dynamics to predict future glucose levels and calculate optimal insulin doses to keep glucose within a target range, all while respecting pre-defined safety constraints to minimize hypoglycemia risk [12] [13] [14].

The core principles of MPC that directly address the limitations of SAP and CSII are:

- Predictive Capability: Unlike reactive systems, MPC anticipates future high and low glucose events, enabling proactive adjustments to insulin infusion [14].

- Multivariable Constraint Handling: MPC can simultaneously manage multiple objectives, such as maximizing Time in Range while strictly enforcing a hard constraint on minimum glucose to prevent hypoglycemia [12] [13].

- Receding Horizon Optimization: The algorithm continuously recalculates the optimal insulin delivery plan based on the most recent CGM reading, making it robust to unmeasured disturbances like stress or unannounced exercise [14].

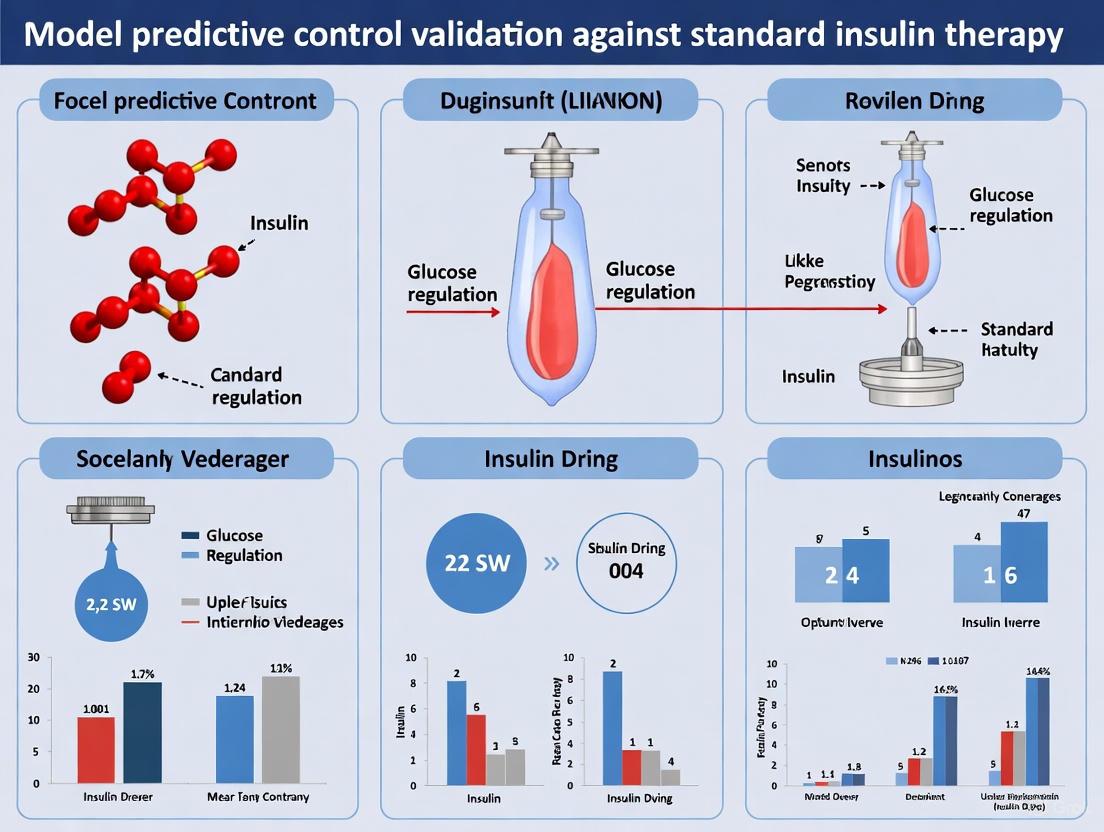

Diagram 1: Model Predictive Control (MPC) feedback loop for automated insulin delivery. The algorithm uses a physiological model to predict glucose levels and calculates optimal insulin doses, implementing only the immediate dose before repeating the process [12] [13] [14].

Experimental Validation: MPC-Driven AID vs. Conventional SAP

Recent real-world studies on AID systems utilizing MPC algorithms provide compelling data that directly validates their superiority over conventional SAP therapy.

Glycemic Outcomes and Protocol

A 2025 retrospective study compared the one-year performance of four different AID systems, including the MiniMed 780G (MM780G) which uses an MPC-based algorithm, in adults with T1DM. The study protocol involved collecting glucometric data from the Asturias Automatic Insulin Devices Registry. Key inclusion criteria were T1D diagnosis, prior use of CSII or MDI, and CGM use. Glucometrics were analyzed at baseline (on pre-AID therapy, which included SAP users) and at 3, 6, and 12 months after AID initiation [11].

The results were striking. After 12 months of AID use, the proportion of patients achieving the composite international consensus target (TIR>70%, TAR<25%, TBR<4%) improved from 9.72% to over 52% [11]. When comparing systems, users of the MM780G system achieved the best results in terms of mean glucose, TIR, and Glucose Management Indicator (GMI) after 12 months [11]. This demonstrates that MPC-driven systems can achieve a level of glycemic control that is largely unattainable with conventional SAP for the majority of users.

Table 2: Glycemic Outcomes with AID (MPC) vs. Pre-AID Baseline (Including SAP) [11]

| Glycemic Parameter | Pre-AID Baseline | 12 Months on AID | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients meeting all targets (TIR>70%, TAR<25%, TBR<4%) | 9.72% | >52% | >42% increase |

| Time in Range (TIR) | Not specified | Best results with MM780G (MPC) | Significant improvement |

| Mean Glucose | Not specified | Best results with MM780G (MPC) | Significant improvement |

Efficacy in Diverse Populations

The adaptability of MPC is further validated by its performance in phenotypically diverse populations, including those with type 2 diabetes (T2D). A large-scale real-world analysis of the MM780G system in over 26,000 users with T2D and high insulin resistance showed consistent glycemic improvements across different cohorts. All user groups, including those with a total daily insulin dose ≥100 IU, achieved a Time in Range (TIR) >70% and Time Below Range (TBR) <1% [15]. This highlights the robustness of the MPC algorithm in managing highly variable and complex gluco-regulatory systems, a challenge that is often difficult to address with static, conventional pump therapy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Technologies

Research into MPC-based AID systems relies on a specific suite of tools and technologies.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Functions for AID Investigation

| Tool/Technology | Function in Research | Example Use in Cited Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Insulin Delivery (AID) System | The integrated device (pump, CGM, algorithm) used as the intervention in clinical studies. | MiniMed 780G, Tandem t:slim X2 with Control-IQ, CamAPS FX [11]. |

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) | Provides real-time, high-frequency interstitial glucose measurements for the control algorithm and outcome assessment. | Guardian Sensor 4 (Medtronic), Dexcom G6 [15] [11]. |

| Model Predictive Control (MPC) Algorithm | The core software that predicts future glucose and calculates insulin doses; the subject of validation. | SmartGuard (MM780G), Control-IQ, Diabeloop [11]. |

| Diabetes Management Software | Platform for retrospective data aggregation and analysis of glucometrics (TIR, TBR, CV, etc.). | CareLink, LibreView, Glooko, CLARITY [9] [11]. |

| Physiological Model | A mathematical representation of glucose-insulin dynamics used internally by the MPC for predictions. | Models of insulin pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics and carbohydrate absorption [12] [13]. |

Diagram 2: Core components of a Model Predictive Control Automated Insulin Delivery system, showing the integration of CGM, algorithm, and pump in a closed feedback loop with the patient [11].

Conventional CSII and SAP therapies, while representing significant milestones in diabetes management, are fundamentally limited by their reactive nature and reliance on user input. Clinical evidence demonstrates their failure to eliminate hyperglycemia for many users, their incomplete protection against hypoglycemia, and the high cognitive burden they impose. Model predictive control emerges as a validated solution to these exact problems. By employing a predictive, optimizing, and automated control strategy, MPC-based AID systems have demonstrated superior glycemic outcomes, including significantly higher Time in Range and a greater proportion of patients achieving international targets, across both T1D and T2D populations. The transition from manual conventional therapies to automated, MPC-driven systems represents a paradigm shift from simply delivering insulin to intelligently governing its physiological effects.

The Artificial Pancreas System (APS), also known as a closed-loop system or automated insulin delivery (AID) system, represents a revolutionary therapeutic approach for diabetes mellitus. By integrating three core components—a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), a control algorithm, and an insulin pump—the APS aims to mimic the glucose-regulating function of a healthy pancreas [16]. This system provides continuous, autonomous adjustment of insulin delivery based on real-time fluctuations in blood glucose levels, significantly reducing the management burden on patients while improving glycemic outcomes [17] [18]. The development of these systems marks a paradigm shift from reactive to proactive diabetes management, leveraging technological advancements to address the persistent challenge of maintaining euglycemia.

The clinical significance of APS is profound, particularly for type 1 diabetes (T1D) where insulin deficiency is absolute. Traditional management with multiple daily injections (MDI) or sensor-augmented pumps (SAP) requires constant vigilance from patients and families [17]. The APS automates the most demanding aspect of care—the continuous titration of insulin delivery—which has been shown to improve time-in-range (TIR), reduce hypoglycemic events, and enhance quality of life [19] [20]. The following schematic illustrates the fundamental operational logic of a closed-loop artificial pancreas system.

Commercial APS Landscape: A Comparative Analysis of Key Systems

The APS landscape has evolved rapidly, with several commercial systems now established as the standard of care for T1D. These systems primarily operate as hybrid closed-loop (HCL) systems, which automate basal insulin delivery but still require user input for meal boluses [17] [18]. More advanced advanced hybrid closed-loop (AHCL) systems have since been developed that add automated correction boluses, further reducing user intervention [17] [19]. The following table provides a structured comparison of leading commercial APS, highlighting their key characteristics and algorithmic foundations.

| System Name (Developer) | System Type | Control Algorithm | Key Features & Indications | Representative Performance Data (TIR %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MiniMed 780G (Medtronic) [17] [19] | AHCL | Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) with Fuzzy Logic | Auto-correction boluses; Suitable for ages 2+ [19] | ~75% (Real-world studies) [19] |

| t:slim X2 with Control-IQ (Tandem) [17] [19] | AHCL | Model Predictive Control (MPC) | Automates basal and correction boluses; Sleep mode feature [19] | ~71-74% (Clinical trials) [19] |

| OmniPod 5 (Insulet) [17] [19] | HCL | Model Predictive Control (MPC) | First tubeless patch pump integrated into a closed-loop system [19] | ~65-70% (Increased from baseline by ~10%) [20] |

| CamAPS FX (CamDiab) [17] [19] | AHCL | Model Predictive Control (MPC) | Approved for use in pregnant women with T1D [19] | ~75% (Pregnant population) [19] |

| iLet Bionic Pancreas (Beta Bionics) [19] | AHCL | Proprietary Algorithm | Requires minimal user input (weight only); Potentially capable of dual-hormone delivery [19] | ~73% (Superior to standard care) [19] |

The performance data in the table above is primarily measured by Time-in-Range (TIR), which is the percentage of time a patient's glucose levels remain within the target range (70-180 mg/dL). This metric, derived from CGM data, has become a key standard for evaluating glycemic control in clinical studies of APS [18]. Real-world evidence and meta-analyses consistently show that these AID systems offer superior glycemic control compared to traditional methods, with an average TIR increase of ~10% and a simultaneous ~50% reduction in time spent in hypoglycemia [20].

Frontiers in APS Research: Beyond Commercial HCL Systems

Current research is focused on overcoming the limitations of commercial HCL systems to achieve fully closed-loop (FCL) operation and improve efficacy in challenging physiological scenarios.

Dual-Hormone Artificial Pancreas (DHAP)

A key frontier is the development of Dual-Hormone Artificial Pancreas (DHAP) systems that administer both insulin and glucagon [17] [21]. This approach offers a physiological counter-regulation mechanism to rapidly mitigate hypoglycemia, a significant advantage over insulin-only systems [21]. Recent studies indicate DHAPs are particularly effective at reducing hypoglycemic events, especially those related to post-meal glucose spikes and physical exercise [21].

Advanced Control Algorithms: Machine Learning and Deep Reinforcement Learning

While commercial systems primarily use PID and MPC algorithms, research is exploring more adaptive, personalized control strategies. Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) has emerged as a promising data-driven approach for achieving FCL control without meal announcements [22]. A recent study implemented a DRL controller with a dual safety mechanism ("proactive guidance + reactive correction") that achieved a median TIR of 87.45% in a simulator, effectively eliminating severe hypoglycemia [22]. Another innovative approach combines Model Predictive Control (MPC) with an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) for time-series glucose prediction. This NN-MPC framework was validated in an in vivo study with T1D rats, achieving a remarkable 88.47% TIR, significantly outperforming the open-source OpenAPS benchmark (71.82% TIR) [23].

Experimental Validation: Methodologies for APS Performance Assessment

Rigorous experimental protocols are essential for validating the efficacy and safety of APS, spanning from controlled clinical trials to real-world observational studies.

Clinical Trial Design

Pivotal trials for regulatory approval are typically randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or crossover studies comparing the investigational APS against a control therapy (e.g., SAP or MDI) over several weeks to months [19] [20]. Key endpoints include change in HbA1c, TIR, and time below range (TBR). For example, a multicenter RCT for the MiniMed 780G system demonstrated a 12% higher TIR in the APS group compared to controls, with an 18% higher nocturnal TIR, highlighting the system's particular benefit overnight [18].

In Vivo Preclinical Models

Preclinical research utilizes animal models, such as streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats, for initial proof-of-concept and 24/7 system testing. The experimental workflow for such a study is complex, requiring specialized equipment and surgical procedures, as shown below.

Performance Metrics and Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome for most contemporary APS studies is CGM-derived metrics as per international consensus [20] [18]. The core metrics are:

- Time-in-Range (TIR): Percentage of CGM readings between 70-180 mg/dL. Goal is typically >70%.

- Time Below Range (TBR): Percentage of readings <70 mg/dL (<54 mg/dL for level 2 hypoglycemia). Goal is <4% (<1% for level 2).

- Time Above Range (TAR): Percentage of readings >180 mg/dL.

- Glucose Management Indicator (GMI): An estimate of HbA1c derived from mean CGM glucose.

- Coefficient of Variation (CV): A measure of glycemic variability.

Statistical analyses compare these metrics between treatment arms using appropriate tests (e.g., paired t-tests for crossover studies, mixed-effects models for longitudinal data) [23].

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function & Application in APS Research |

|---|---|

| T1DiabetesGranada Dataset [21] | A detailed, open-access longitudinal dataset for 736 T1D patients. Used for training and validating machine learning models for glucose prediction and event classification. |

| Simglucose Simulator [22] | An open-source simulation environment for in silico testing of APS control algorithms. Allows for efficient and safe testing of new controllers against a virtual cohort of T1D patients. |

| Open Artificial Pancreas System (OpenAPS) [23] | An open-source APS platform used as a benchmark or development foundation in research. Provides a reference for real-life control performance. |

| Bergman Minimal Model (BMM) [21] | A widely accepted mathematical model of glucose-insulin dynamics. Serves as the physiological basis for designing and simulating feedback controllers in APS. |

| Streptozotocin (STZ) [23] | A chemical compound used to selectively destroy pancreatic beta cells in laboratory animals (e.g., rats). Essential for creating an in vivo T1D model for preclinical APS testing. |

| Nonlinear Autoregressive Network with Exogenous Inputs (NARX) [23] | A type of recurrent dynamic neural network. Used for multi-step ahead blood glucose level prediction based on past CGM values, insulin doses, and other inputs. |

The integration of CGM, advanced control algorithms, and insulin pumps in the Artificial Pancreas System has fundamentally transformed the management of type 1 diabetes. Commercial HCL and AHCL systems have proven their mettle through extensive clinical validation, consistently demonstrating superior glycemic control versus previous standards of care. Research continues to push the boundaries toward fully closed-loop systems utilizing dual-hormone delivery and sophisticated algorithms like DRL and NN-MPC. The ongoing validation of these systems within the framework of model predictive control and other advanced strategies not only promises to further alleviate the patient burden but also to provide a robust, personalized, and safe therapeutic option for a growing number of insulin-dependent individuals.

Model Predictive Control (MPC) represents a significant advancement in automated insulin delivery systems for diabetes management. Unlike traditional control methods, MPC is an advanced process control strategy that uses an internal dynamic model to predict future system behavior and optimize control actions over a finite time horizon, a capability that is absent in conventional PID controllers [14]. This proactive approach is particularly suited for managing the complex and highly variable physiology of blood glucose regulation. The core strength of MPC lies in its ability to systematically handle constraints—such as maximum safe insulin doses—and to be personalized for individual patient needs, thereby enhancing both safety and efficacy [14] [24]. This guide objectively compares the performance of MPC-based artificial pancreas systems against standard insulin therapies, framing the analysis within the broader thesis of validating MPC's role in diabetes treatment for a research-focused audience.

Performance Comparison: MPC vs. Standard Therapies

Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials provide robust quantitative evidence for comparing MPC-based artificial pancreas systems with conventional insulin therapy. The data, summarized in the table below, highlight performance differences across key glycemic control metrics.

Table 1: Glycemic Control Outcomes: MPC vs. Conventional Insulin Therapy

| Outcome Measure | Therapy | Performance (Mean Difference, %) | Statistical Significance (p-value) | Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time in Target Range (3.9-10 mmol/L) | MPC-Based AP | +10.03% (95% CI: 7.50, 12.56) | p < 0.00001 [25] | Overnight Use |

| Time in Hypoglycemia (< 3.9 mmol/L) | MPC-Based AP | -1.34% (95% CI: -1.87, -0.81) | p < 0.00001 [25] | Overnight Use, >1 Month Follow-up |

| Hypoglycemia Risk | MPC with IOB Constraint | 10% of simulations [24] | Not Provided | In-silico Simulation |

| Hypoglycemia Risk | Control without IOB Constraint | 50% of simulations [24] | Not Provided | In-silico Simulation |

The data demonstrates that MPC algorithms significantly improve glycemic control by increasing time in the target range while concurrently reducing hypoglycemic risk, a critical challenge in intensive insulin therapy [26] [25]. The in-silico data further underscores the importance of specific safety constraints in achieving these safety outcomes.

Core Advantages of MPC in Diabetes Management

Proactive and Predictive Control

MPC's fundamental advantage is its predictive nature. Instead of merely reacting to current glucose levels like traditional PID controllers or manual injections, MPC uses a dynamic model of the patient's glucose-insulin dynamics to forecast future glucose trajectories [14] [24]. This allows the algorithm to anticipate and proactively counteract hyperglycemic and hypoglycemic events. For instance, if the model predicts a falling glucose trend, MPC can reduce or suspend insulin infusion before hypoglycemia occurs, a capability that is absent in reactive therapies [14] [27].

Systematic Constraint Handling

The ability to explicitly incorporate system constraints into its optimization problem is a key selling point of MPC [14] [28]. In an artificial pancreas, critical safety constraints include:

- Insulin on Board (IOB) Constraint: This dynamic safety constraint uses the insulin delivery history and an estimate of active insulin in the body to prevent over-delivery and hypoglycemia [24].

- Input and Output Limits: The algorithm can be configured to respect maximum and minimum insulin infusion rates (input limits) and to maintain glucose within a predefined safe range (output limit) [24] [28].

Research has shown that incorporating an IOB constraint can drastically reduce hypoglycemic events, from 50% of simulations without the constraint to just 10% with it [24]. This systematic handling of constraints ensures that aggressive control actions for high glucose do not lead to dangerous lows.

Personalization and Adaptation

MPC frameworks are inherently suited for personalization, which is crucial given the significant inter- and intra-subject variability in insulin sensitivity and response [24] [29]. Personalization occurs on multiple levels:

- Model Personalization: The internal predictive model can be tailored to an individual's physiology using data from clinical experiments [24].

- Parameter Tuning: Key parameters like the insulin-to-carbohydrate ratio (I:C) and correction factor (CF) can be empirically determined for each patient and incorporated into the control law [24].

- Adaptive Frameworks: Emerging research, such as the "ChatMPC" concept, explores using natural language interaction to allow users to personalize control behavior and provide real-time environmental information, further adapting the system to individual needs and changing conditions [30].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Clinical Trial Design

The quantitative findings in this guide are primarily derived from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses thereof. A typical protocol involves:

- Participants: Outpatients with type 1 diabetes, including adults and children [25].

- Intervention: Use of an MPC-based artificial pancreas system consisting of a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), the MPC control algorithm, and an insulin pump [25].

- Comparator: Conventional insulin therapy, such as sensor-augmented pumps (SAP) or continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) [25].

- Outcomes: Primary outcome is the percentage of time in the target glucose range (3.9–10 mmol/L). Key secondary outcomes include time in hypoglycemia (< 3.9 mmol/L) and total daily insulin dose [25].

- Duration: Trials range from short-term (single night) to longer-term studies (over one month) to assess both immediate efficacy and sustained performance [25].

In-Silico Testing

Before clinical implementation, MPC algorithms undergo extensive validation in simulation environments. The core methodology includes:

- Simulation Platform: Use of FDA-approved simulation environments, such as the one based on the T1DM model of Dalla Man et al., which contains a cohort of virtual patients representing a wide range of physiologies [24].

- Model Identification: Developing the internal MPC model, often an Auto-Regressive eXogenous (ARX) model, from input-output data collected in clinical experiments [24]. The model takes the form:

y(k) = αy(k-1) + βy(k-2) + γu(k-1), whereyis glucose anduis insulin. - Robustness Testing: Evaluating controller performance under uncertainty by using a model identified from one virtual subject to control others, and by adding measurement noise (e.g., 50% normal random noise) to simulate real-world CGM inaccuracy [24].

- Constraint Implementation: Testing the safety constraints, where the maximum insulin delivery

U_max(k)is dynamically calculated based on IOB to override aggressive control moves [24].

System Workflow and Logic

The following diagram illustrates the core operational logic of an MPC-based artificial pancreas system, integrating proactive prediction, constraint handling, and personalized control.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Components for Artificial Pancreas Research

| Component | Function in Research | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) | Provides real-time, high-frequency glucose measurements as the primary input to the control algorithm. | Critical for both in-patient studies and real-world system operation [25]. |

| Insulin Pump | Acts as the final control element, delivering subcutaneously calculated insulin doses. | Often integrated with the CGM and algorithm on a single platform [25]. |

| MPC Software Framework | The core implementation of the control algorithm that performs prediction and optimization. | Open-source tools like ACADOS and GRAMPC facilitate development and testing [14]. |

| In-Silico Simulator | A mathematical simulation environment for pre-clinical testing and validation of control algorithms. | FDA-approved simulators (e.g., based on the Dalla Man model) use virtual patient cohorts [24]. |

| Dynamic System Model | The internal model (e.g., ARX model) used by the MPC to predict glucose-insulin dynamics. | y(k)=αy(k-1)+βy(k-2)+γu(k-1); identified from clinical data [24]. |

| Personalization Parameters | Patient-specific parameters that tailor the algorithm to an individual's physiology. | Insulin-to-Carbohydrate Ratio (I:C), Correction Factor (CF), and total daily insulin [24]. |

The validation of Model Predictive Control against standard insulin therapy, as demonstrated by meta-analyses of clinical trials and in-silico studies, confirms its key advantages in proactive control, systematic constraint handling, and personalization. MPC-based systems consistently show a statistically significant improvement in maintaining target glycemia while reducing hypoglycemia, a critical trade-off in diabetes management. The incorporation of safety constraints like IOB is fundamental to this success. For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings validate MPC as a robust and safe technological framework for the next generation of automated insulin delivery systems, with ongoing innovation focused on further enhancing adaptability and user-specific customization.

Implementing and Personalizing MPC Algorithms for Glycemic Control

In the pursuit of precision medicine for diabetes management, model individualization has emerged as a critical capability for optimizing treatment outcomes. The validation of Model Predictive Control (MPC) against standard insulin therapy research depends fundamentally on the ability to create accurate, personalized models of an individual's glucose-insulin physiology. Two dominant paradigms have emerged for achieving this personalization: physiological modeling grounded in mechanistic understanding of biological processes, and data-driven approaches that leverage machine learning to extract patterns from individual patient data [31] [32] [33]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these strategies, examining their methodological foundations, experimental validation, and performance in artificial pancreas systems.

Physiological Modeling Approaches

Foundation in Biological Mechanisms

Physiological models are built upon mathematical representations of known biological systems and processes. These models employ differential equations to describe the fundamental physiology of glucose-insulin regulation, including glucose absorption, insulin secretion and kinetics, and glucose utilization by tissues [31] [33]. For diabetes management, the Padova model represents a landmark achievement - a physiologically-based mathematical model of the glucose-insulin system that has been accepted by regulatory authorities for in-silico testing of control algorithms [34].

The core strength of physiological models lies in their interpretability; each parameter corresponds to a specific physiological quantity, such as insulin sensitivity or glucose effectiveness. This mechanistic foundation allows researchers to make clinically meaningful adjustments based on physiological understanding rather than black-box optimization [31]. For instance, Huang et al. developed a diabetes treatment model using differential equations that theoretically demonstrates unique, globally stable periodic solutions for T1DM patients and system persistence for T2DM patients [31].

Individualization Methodologies

Physiological models are individualized through parameter estimation, where key physiological parameters are adjusted to match an individual's characteristics and response patterns:

Demographic Personalization: Basic individualization incorporates demographic data including height, weight, age, and sex, which rescores average organ volumes and blood flows [33].

Physiological Measurement Integration: Advanced personalization incorporates directly measured physiological parameters such as liver blood flow (measured via MRI), glomerular filtration rate, and hematocrit levels [33].

Hybrid Mechanistic-ML Approaches: Emerging strategies combine physiological models with machine learning, using techniques like expansion state observers (ESO) to dynamically estimate disturbances and unmodeled dynamics in real-time [34].

A study on physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling of caffeine demonstrated the progressive improvement in prediction accuracy achieved through stepwise personalization. The percentage of predictions within 1.25-fold of observed values increased from 45.8% (base model) to 66.15% when demography, physiology, and enzyme activity were all individualized [33].

Table 1: Performance Improvement with Stepwise Physiological Model Personalization

| Personalization Level | Prediction Accuracy (% within 1.25-fold) | Key Personalized Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Base Model | 45.8% | Population averages |

| Demography Only | 57.8% | Height, weight, age, sex |

| Demography + Physiology | 59.1% | Liver blood flow, GFR, hematocrit |

| Full Personalization | 66.15% | Demography, physiology, CYP1A2 activity |

Data-Driven Modeling Approaches

Foundation in Pattern Recognition

Data-driven approaches bypass explicit physiological modeling in favor of extracting predictive patterns directly from individual data streams. These methods leverage machine learning algorithms to establish correlations between inputs (e.g., continuous glucose monitor readings, heart rate, acceleration) and outcomes (e.g., future glucose values, hypoglycemia events) without requiring a priori physiological knowledge [32].

The fundamental premise of data-driven individualization is that individuals exhibit unique but consistent patterns in their physiological responses that can be discovered through statistical analysis of sufficient data. Rather than modeling the underlying biological processes, these approaches model the individual's manifestation of those processes through their data signatures [32].

Individualization Methodologies

Data-driven individualization employs various machine learning techniques to create personalized predictive models:

Individual-Specific Classifiers: Random forests and k-nearest neighbor classifiers trained exclusively on individual data have demonstrated superior performance for predicting psychological and physiological states compared to general models [32].

Feature Extraction from Time-Series: Algorithms automatically extract relevant features from physiological time-series data (e.g., electrodermal activity, heart rate variability) that correlate with target states like stress or glycemic events [32].

Digital Twin Creation: Generative AI and deep learning techniques create virtual patient representations that can be personalized using individual data, enabling prediction of individual drug responses and optimization of dosing strategies [35].

A critical study comparing individual-specific versus general models for predicting affective arousal states found that models tailored to individuals significantly outperformed population-level models, demonstrating the value of personalized pattern recognition over one-size-fits-all approaches [32].

Table 2: Data-Driven Model Performance for Individual State Prediction

| Model Type | Prediction Accuracy | Data Requirements | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| k-Nearest Neighbor with Dynamic Time Warping | Moderate | High temporal density | Low |

| Random Forests with TSFRESH Features | High | Moderate with feature engineering | Medium |

| Individual-Specific Random Forests | Highest | Extensive individual data | High |

| General Population Model | Lower | Diverse population data | Low |

Comparative Experimental Evaluation

Performance in Artificial Pancreas Systems

The ultimate validation of model individualization strategies occurs in their application to closed-loop glucose control systems. Comparative studies using the FDA-accepted UVA/Padova T1DM simulator have revealed distinct performance characteristics for different approaches:

Self-Anti-Disturbance Control with Basal Estimation: This physiological approach combined with dynamic parameter estimation demonstrated robust performance under challenging conditions with incorrectly specified basal rates. In scenarios with over-estimated basal rates, this method maintained glucose in target range (70-180 mg/dL) for 89.6% of time with announced meals and 71.8% with unannounced meals, outperforming zone Model Predictive Control (zMPC) in safety metrics [34].

Zone Model Predictive Control: This established physiological control strategy showed strong performance under normal conditions but greater susceptibility to incorrect basal parameter specification. With over-estimated basal rates and unannounced meals, zMPC maintained glucose in target range only 58.6% of the time, with 3.2% of values falling dangerously below 54 mg/dL [34].

Differential Equation-Based Exercise Modeling: Physiological models incorporating exercise parameters have quantified the glycemic impact of different exercise intensities, demonstrating that high-intensity aerobic exercise can trigger hypoglycemic events (<3.89 mmol/L), while low-to-moderate intensity provides safer glycemic management [31].

Table 3: Control Algorithm Performance Under Basal Rate Misspecification

| Control Scenario | Control Algorithm | Time in Target Range | Time <54 mg/dL | Time >250 mg/dL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2x Basal, Announced Meals | zMPC | 83.7% | 0% | 0% |

| 2x Basal, Announced Meals | ADRC with Basal Estimation | 89.6% | 0% | 0% |

| 2x Basal, Unannounced Meals | zMPC | 58.6% | 3.2% | 3.2% |

| 2x Basal, Unannounced Meals | ADRC with Basal Estimation | 71.8% | 0% | 2.5% |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Robust validation of individualized models requires standardized experimental protocols:

UVA/Padova Simulator Testing Protocol

- Population: 100 virtual adult subjects with T1DM characteristics

- Duration: 48-hour simulation with three main meals and optional snacks

- Conditions: Variations in basal rate accuracy (50%-200% of true requirement)

- Meal Scenarios: Both announced and unannounced meal challenges

- Performance Metrics: Percentage time in ranges (hypoglycemia, target, hyperglycemia), glucose variability indices, safety metrics [34]

Empirical Exercise Response Protocol

- Population: T1DM and T2DM virtual cohorts

- Exercise Interventions: Low (q2=0.1), medium (q2=0.4), and high intensity (q2=0.7) aerobic exercise

- Measurements: Continuous glucose monitoring, insulin infusion rates

- Analysis: Blood Glucose Risk Index (BGRI) calculation quantifying low and high glucose risks [31]

Ecological Momentary Assessment Protocol

- Population: 25 participants wearing Empatica E4 wristbands

- Duration: 4-week continuous monitoring with 6 daily self-reports

- Data Streams: Electrodermal activity, heart rate, acceleration, self-reported arousal

- Model Training: Individual-specific random forest classifiers using tsfresh-extracted features [32]

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents and Platforms for Model Individualization Research

| Research Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| UVA/Padova T1DM Simulator | FDA-accepted platform for in-silico testing of glucose control algorithms | Validation of physiological MPC strategies [34] |

| Empatica E4 Wristband | Wearable physiological monitor capturing EDA, ACC, BVP, HR | Passive data collection for data-driven model training [32] |

| PK-Sim & MoBi Toolbox | PBPK modeling software with MATLAB integration | Mechanistic model personalization and sensitivity analysis [33] |

| TSFRESH Python Package | Automated time-series feature extraction | Feature generation for machine learning classification [32] |

| Open Systems Pharmacology Suite | Open-source platform for PBPK/PD modeling | QSP model development and personalization [33] |

Visualization of Modeling Approaches

The fundamental differences between physiological and data-driven individualization strategies can be visualized through their distinct methodological workflows:

Model Individualization Methodological Pathways

The workflow visualization illustrates how physiological modeling begins with established biological knowledge and population parameters, then incorporates individual demographic and physiological measurements to estimate personalized parameters through mechanistic frameworks. In contrast, data-driven approaches begin with raw individual sensor data, employ feature extraction and machine learning to discover predictive patterns, and produce models optimized for individual prediction without explicit physiological representation.

The comparison between physiological and data-driven model individualization strategies reveals a complementary relationship rather than a strict superiority of either approach. Physiological models provide interpretability and mechanistic insight, which is particularly valuable for clinical understanding and regulatory acceptance. Data-driven approaches offer flexibility in capturing unique individual patterns that may not be fully represented by simplified physiological models. The most promising direction emerging from current research involves hybrid approaches that combine mechanistic understanding with data-driven personalization, such as the self-anti-disturbance control with basal rate estimation that demonstrated robust performance across challenging scenarios. As artificial intelligence and physiological modeling continue to converge, the distinction between these approaches may blur, leading to more sophisticated and effective individualized models for diabetes management and beyond.

Leveraging AI and LSTM Networks for Enhanced Blood Glucose Prediction

The global challenge of diabetes management has been significantly transformed by the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) technologies. For researchers and drug development professionals, accurate blood glucose level (BGL) prediction represents a critical component in the development of automated insulin delivery systems and model predictive control (MPC) frameworks. These predictive models serve as the foundational intelligence that enables proactive rather than reactive glycemic management, potentially revolutionizing treatment outcomes for the estimated 537 million adults affected worldwide [36]. The emergence of sophisticated neural network architectures, particularly Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, has dramatically improved our ability to forecast glucose fluctuations with clinically relevant precision and extended prediction horizons.

This analysis provides a comprehensive comparison of current AI-driven BGL prediction methodologies, with particular emphasis on their validation within MPC systems for diabetes management. We objectively evaluate model performance against traditional approaches, present detailed experimental protocols from key studies, and provide essential resources for research and development teams working at the intersection of AI and diabetic therapeutics.

Comparative Analysis of Blood Glucose Prediction Models

Performance Metrics Across Model Architectures

Table 1: Performance comparison of AI models for blood glucose prediction (RMSE in mg/dL)

| Model Architecture | Prediction Horizon | RMSE Performance | Key Advantages | Clinical Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM with Temporal Features [37] | 60 minutes | 10.93 mg/dL | Captures temporal dependencies; handles sequential data | Validated on 12 patients with CGM data |

| Transformer-LSTM Hybrid [38] | 120 minutes | 13.986 mg/dL | Captures long-range dependencies; extended prediction horizon | Clark Grid Analysis: >96% in clinical safety zone |

| LSTM-XGBoost Fusion [37] | 30 minutes | 9.63 mg/dL | Combines sequential learning with feature importance | Superior short-term accuracy |

| Traditional Machine Learning [39] | 30 minutes | Varies by approach | Fast training; high interpretability | Comprehensive statistical validation on Ohio datasets |

| Memory-Augmented LSTM (MemLSTM) [40] | 30-60 minutes | Improved over baselines | Case-based reasoning; attention mechanisms | Testing on synthetic and real-patient data |

| Deep Learning with Physiological Data [41] | 30-60 minutes | Varies with input variables | Incorporates heart rate, steps, carbohydrates | Uses multimodal wearable data |

Input Variable Impact on Prediction Accuracy

Table 2: Effect of input variables on prediction performance across model types

| Input Variables | LSTM Performance | Traditional ML Performance | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| CGM data only [39] | Moderate accuracy (univariate) | Fast training; moderate accuracy | Practical for real-world application |

| CGM + Insulin + Carbs [39] | High accuracy with quality data | Varies with feature engineering | Physiologically comprehensive |

| CGM + Heart Rate + Activity [41] [42] | Improved trend prediction | Limited improvement | Captures exercise impacts |

| Meal Composition + Insulin [38] | Enhanced personalization | N/A | High relevance for MPC systems |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Frameworks

LSTM and Hybrid Model Development

The experimental protocol for developing LSTM-based glucose prediction models typically follows a structured pipeline. Data acquisition begins with CGM devices (e.g., Medtronic Guardian Sensor 3) that collect interstitial glucose measurements at 5-minute intervals [41]. For comprehensive modeling, additional physiological data may include heart rate (from Fitbit Charge 4 or similar devices), step counts, and self-reported carbohydrate intake and insulin administration [41] [39].

Data preprocessing is critical for model performance. Raw CGM data typically undergoes linear interpolation for missing values (limited to gaps ≤1 hour), temporal alignment of all variables to consistent 5-minute intervals, and signal smoothing for impulsive inputs like carbohydrates and insulin using physiological filters based on established models (e.g., Hovorka model) [41]. For carbohydrate inputs, a two-compartment gut absorption model is often applied, characterized by differential equations that convert raw carbohydrate intake into glucose absorption rates, providing smoother, more physiologically relevant input signals to the models [41].

The model architecture for LSTM networks typically involves input layers that accept sequential data (e.g., 60-90 minutes of historical glucose values), followed by multiple LSTM layers with 50-100 units each, dropout layers for regularization (0.2-0.5 dropout rates), and fully connected layers for output predictions [40] [37]. The sliding window approach is standard, where the model uses recent historical data to predict glucose values at future time points (30, 60, 90, or 120 minutes ahead) [38]. Training generally employs mean squared error (MSE) or root mean square error (RMSE) as loss functions, with Adam optimizer and learning rates between 0.001 and 0.01 [37].

Model Validation Frameworks

Validation of BGL prediction models employs both regression-based metrics and clinical accuracy assessments. Standard regression metrics include Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Time Gain (TG) [37] [39]. For clinical validation, the Clarke Error Grid Analysis (EGA) is essential, categorizing predictions into zones A (clinically accurate), B (clinically acceptable), C (may lead to unnecessary corrections), D (potentially dangerous failure to detect), and E (erroneous treatment) [38]. High-performing models typically achieve >96% of predictions in zones A and B for horizons up to 120 minutes [38].

Rigorous statistical analysis is crucial for meaningful comparison between approaches. Studies should employ paired t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests to compare model performance across patients, and repeated measures ANOVA to evaluate performance across different prediction horizons [39]. Validation should use appropriate dataset splits (typically 70-80% training, 10-15% validation, 10-15% testing) with patient-wise splitting rather than random temporal splitting to ensure realistic evaluation [39].

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational resources for BGL prediction studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Datasets | OhioT1DM Dataset [40] [39] | Model training and benchmarking | CGM, insulin, carbs, heart rate; 12 patients with T1D |

| DiaTrend Dataset [41] | Multimodal model development | CGM, heart rate, steps, carbs; free-living conditions | |

| Software Libraries | TensorFlow/PyTorch [37] [38] | Deep learning implementation | LSTM, Transformer architectures |

| scikit-learn [39] | Traditional ML models | Random Forest, SVM, Bayesian methods | |

| VOSviewer/CiteSpace [43] | Bibliometric analysis | Research trend visualization | |

| Clinical Validation Tools | Clarke Error Grid Analysis [38] | Clinical accuracy assessment | Zones A-E for clinical relevance |

| Statistical Tests [39] | Performance comparison | Paired t-tests, Wilcoxon, ANOVA | |

| Wearable Devices | Medtronic CGM [41] [39] | Glucose data collection | 5-minute sampling; clinical grade |

| Fitbit/Activity Trackers [41] [42] | Physiological data collection | Heart rate, activity, sleep patterns |

Integration with Model Predictive Control Systems

The validation of AI-driven prediction models within model predictive control (MPC) frameworks represents a critical research direction with significant clinical implications. MPC systems for automated insulin delivery rely on accurate glucose predictions to calculate optimal insulin dosages, creating a closed-loop system that mimics pancreatic function [43] [44]. The integration of LSTM-based predictors has demonstrated particular promise in these systems due to their ability to model complex temporal patterns in glucose dynamics.

Recent advances show that hybrid closed-loop systems incorporating AI predictions outperform non-automated systems, improving time in target glucose range by approximately 8-12 percentage points, reducing hyperglycemia exposure, and maintaining or reducing hypoglycemia risk [44]. The transition from laboratory environments to clinical applications requires rigorous validation of these integrated systems, with particular attention to safety constraints, meal detection algorithms, and adaptation to individual patient responses.

The integration of LSTM networks and hybrid AI architectures has substantially advanced the field of blood glucose prediction, enabling longer prediction horizons with clinically acceptable accuracy. For research teams focused on validating MPC against standard insulin therapy, these predictive models provide the critical intelligence layer that enables more responsive and personalized glycemic control.

Future research priorities should address several key challenges: improving model interpretability for clinical adoption, enhancing generalizability across diverse patient populations, developing effective transfer learning approaches for patient-specific adaptation, and establishing standardized benchmarks for fair comparison of emerging architectures [44] [42]. The promising results from recent studies, particularly those achieving >96% clinical accuracy on Clarke Error Grid Analysis for extended prediction horizons [38], suggest that AI-enhanced MPC systems may soon set new standards for diabetes management, potentially transforming care for millions of patients worldwide.

For research teams embarking on MPC validation studies, the experimental protocols and performance benchmarks provided herein offer a foundational framework for designing rigorous, clinically relevant evaluations of these emerging technologies.

The validation of Model Predictive Control (MPC) against standard insulin therapy represents a pivotal advancement in diabetes management research. Artificial pancreas systems, which automate insulin delivery through the integration of continuous glucose monitors (CGM), control algorithms, and insulin pumps, have fundamentally reshaped treatment paradigms for type 1 diabetes (T1D) [19]. Central to these systems is the model predictive control algorithm, which uses a mathematical model of a patient's glucose-insulin dynamics to forecast future glucose levels and preemptively calculate optimal insulin doses [25]. The core challenge in this domain has shifted from basic automation to sophisticated personalization—adapting these systems to individual physiological characteristics, behaviors, and changing metabolic needs.

Personalization frameworks in MPC systems generally focus on individualizing the model parameters, refining the cost function, or both. The model encapsulates the patient's unique gluco-regulatory dynamics, while the cost function defines the optimization targets, balancing glucose control objectives with safety constraints. Research indicates that the most effective systems often employ dual personalization strategies, adapting both components to achieve superior clinical outcomes [45] [1]. This comparative guide examines the performance of various personalized MPC implementations against standard insulin therapies, analyzing the experimental data and methodologies that underscore their efficacy and safety profiles for research and development professionals.

Comparative Analysis of Personalized MPC vs. Standard Therapy

Table 1: Clinical Outcomes of Personalized MPC vs. Standard Insulin Therapy

| Study Population & System | Time in Range (TIR) 70-180 mg/dL | Time in Hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL) | Time in Hyperglycemia (>250 mg/dL) | Key Personalization Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults (Omnipod HCL) [45] | HCL: 73.7%ST: 68.0% (P=0.08) | HCL: 1.9%ST: 3.1% (P=0.005) | HCL: 4.5%ST: 7.3% (P=0.1) | Personalized Model Parameters (MPC) |

| Adolescents (Omnipod HCL) [45] | HCL: 79.0%ST: 60.6% (P=0.01) | HCL: 2.5%ST: 2.9% (P=0.3) | HCL: 3.5%ST: 11.9% (P=0.02) | Personalized Model Parameters (MPC) |

| Children (Omnipod HCL) [45] | HCL: 69.2%ST: 54.9% (P=0.003) | HCL: 2.2%ST: 2.8% (P=0.3) | HCL: 8.6%ST: 17.1% (P=0.03) | Personalized Model Parameters (MPC) |

| Overnight MPC Use (Meta-Analysis) [25] | MPC: +10.03%(95% CI [7.50, 12.56], p<0.00001) | MPC: -1.34%(95% CI [-1.87, -0.81], p<0.00001) | Not Reported | Varied (Model & Cost Function) |

| Diabetic Rats (i-AiDS) [1] | 83.4% (within 80-180 mg/dL) | 3.62 ± 1.8 mild events per subject | No severe events | Offset-free MPC (Handles model mismatch) |

Table 2: Algorithm and Personalization Features in Commercial AID Systems

| System/Algorithm | Core Algorithm Type | Personalization Scope | Key Feature | Reported Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OmniPod 5 [45] [19] | Personalized MPC | Model Parameters | Learns individual insulin needs | Significant TIR improvements in all age groups [45] |

| Tandem t:slim X2 & Mobi [19] | MPC (Control-IQ) | Model & Cost Function | Automated basal & correction boluses | Successful real-world use; NEJM publications [19] |

| Medtronic 780G [19] | PID + Fuzzy Logic | Cost Function (Automated correction boluses) | Hybrid algorithm | Real-world outcomes reported [19] |

| CamAPS FX [19] | MPC | Model & Cost Function | First approved for pregnancy with T1D | Clinical trials featured in NEJM [19] |

| iLet Bionic Pancreas [19] | MPC | Model & Cost Function | Requires minimal user input | Featured in NEJM clinical trials [19] |

The quantitative data reveals a consistent trend: personalized MPC systems significantly outperform standard insulin therapy, primarily by increasing Time in Range (TIR) while reducing hyperglycemic exposure. The meta-analysis of overnight use provides compelling evidence, showing a statistically significant 10% absolute improvement in TIR and a 1.34% reduction in hypoglycemia [25]. The Omnipod personalized MPC algorithm demonstrated particularly strong results in adolescent populations, achieving a 79% TIR compared to 60.6% with standard therapy [45]. Furthermore, the preclinical validation in diabetic rats achieved an remarkable 83.4% TIR, demonstrating the potential of advanced offset-free MPC controllers to handle plant-model mismatch and external disturbances like unannounced meals [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Clinical Trial Design for AP Systems

The gold standard for validating artificial pancreas systems is the randomized controlled trial (RCT), often employing a crossover design. A typical protocol involves:

- Participant Recruitment: Studies typically enroll participants with T1D across various age groups (children, adolescents, adults). Key eligibility criteria often include a specific HbA1c threshold (e.g., <10.0%) and current use of insulin pump therapy or multiple daily injections [45].

- Study Phases:

- Run-In/Standard Therapy (ST) Phase: Participants use their usual diabetes management (e.g., sensor-augmented pump) for a period (e.g., 7 days) to establish baseline data [45].

- Intervention/Hybrid Closed-Loop (HCL) Phase: Participants use the investigational personalized MPC system for a defined period, ranging from a few days in early feasibility studies to several months in larger trials. To simulate real-world conditions, this phase often occurs in supervised hotel or free-living settings with challenges like unrestricted meals and daily physical activity [45] [25].

- Data Collection & Analysis: Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) data is collected throughout both phases. Primary endpoints are typically the percentage of time in target range (3.9-10 mmol/L or 70-180 mg/dL), time in hypoglycemia (<3.9 mmol/L or <70 mg/dL), and time in hyperglycemia (>10 or >13.9 mmol/L, or >180 or >250 mg/dL). Statistical analyses (e.g., paired t-tests) compare the outcomes between the HCL and ST phases [45] [25].

Preclinical Validation in Animal Models

Before human trials, MPC algorithms undergo rigorous preclinical testing.

- Animal Model Induction: Studies use animal models like male Wistar rats, where diabetes is induced chemically (e.g., with streptozotocin) [1].

- System Setup and Tuning: Researchers implant a CGM and a customized insulin pump. The initial phase often involves manual insulin injections to record the glucose response and perform an off-line parametric estimation for the model. Controller parameters are then tuned via simulation based on the identified model [1].

- Autonomous Testing: Finally, the system is tested in a fully autonomous mode over an extended period (e.g., 72 hours). The controller's performance is assessed by its ability to maintain glucose within a target range (e.g., 80-180 mg/dL) and handle unannounced carbohydrate intake and other physiological disturbances [1].

Visualization of Personalization Frameworks and Workflows

Personalization Framework for MPC in an Artificial Pancreas

This diagram illustrates the two primary axes for personalization in an MPC system for diabetes: the physiological model and the cost function.

Typical Clinical Validation Workflow for a Personalized MPC System

This workflow outlines the key stages from initial algorithm development to the final assessment of a personalized MPC system in a clinical trial.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for AP and Personalized MPC Research

| Reagent / Solution / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) | Measures interstitial fluid glucose levels in near-real-time, providing the essential feedback signal for the control algorithm [19]. |

| Insulin Infusion Pump | Delects subcutaneously infused insulin according to commands from the control algorithm [19]. |

| Control Algorithm (MPC) | The core "brain" of the system; uses a model to predict future glucose levels and computes optimal insulin doses [25] [19]. |

| In-Silico Simulator (e.g., FDA-Accepted T1D Simulator) | A virtual population of patients with T1D used for initial testing and refinement of control algorithms, reducing the need for animal and early human trials [19]. |

| Animal Models (e.g., STZ-induced Diabetic Rats) | Provides a pre-clinical model for testing the safety and efficacy of the integrated system (sensor, algorithm, pump) in a living organism [1]. |

| Streptozotocin (STZ) | A chemical compound used in research to selectively destroy pancreatic beta cells in animal models, inducing an experimental form of diabetes [1]. |

The evidence from clinical trials and meta-analyses firmly establishes that personalized MPC frameworks, whether they individualize the model, cost function, or both, yield statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in glycemic outcomes compared to standard insulin therapy. The consistent enhancement in Time in Range, coupled with reductions in hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, underscores the transformative role of personalization in diabetes technology. Future research directions highlighted in the literature include the integration of dual-hormone (insulin and glucagon) systems, the application of machine learning for fully adaptive personalization, and the expansion of these technologies to populations with type 2 diabetes. For researchers and drug development professionals, the continued refinement of these personalization frameworks represents the frontier in the quest to fully automate and optimize diabetes management.

The management of type 1 diabetes (T1D) has been profoundly transformed by automated insulin delivery (AID) systems. These systems aim to reduce the cognitive burden of diabetes while improving glycemic outcomes. Within this field, a critical research focus is the validation of advanced control algorithms, particularly Model Predictive Control (MPC), against standard insulin therapy. MPC-based algorithms predict future glucose levels to proactively adjust insulin delivery, a feature that is crucial for managing the complex challenges of meal consumption and physical activity. This guide objectively compares the performance of contemporary Hybrid Closed-Loop (HCL) systems, framing their efficacy within the broader thesis of MPC validation. The data presented serves the needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals by summarizing experimental outcomes and detailed methodologies from recent clinical investigations.

Performance Comparison of Hybrid Closed-Loop Systems

The following tables synthesize quantitative glycemic outcomes and key characteristics from recent studies and real-world evidence, comparing different AID systems and their approaches to meal and exercise management.

Table 1: Comparative Glycemic Outcomes from Clinical Studies and Real-World Evidence