Model Predictive Control for Blood Glucose Regulation: Algorithm Design, Clinical Validation, and Future Directions

This comprehensive review examines Model Predictive Control (MPC) algorithms for automated blood glucose regulation in type 1 diabetes.

Model Predictive Control for Blood Glucose Regulation: Algorithm Design, Clinical Validation, and Future Directions

Abstract

This comprehensive review examines Model Predictive Control (MPC) algorithms for automated blood glucose regulation in type 1 diabetes. We explore foundational MPC principles and their application in artificial pancreas systems, detailing methodological advances including adaptive tuning strategies and data-driven predictors using LSTM networks. The analysis covers troubleshooting challenges like model inaccuracies and optimization techniques, alongside rigorous clinical validation through comparative trials against PID control and conventional insulin therapy. Synthesizing evidence from recent clinical studies and meta-analyses, this article provides researchers and drug development professionals with a thorough technical foundation and critical assessment of MPC performance, safety considerations, and future research trajectories in closed-loop glucose management.

Fundamental Principles and Clinical Rationale for MPC in Glucose Regulation

The artificial pancreas (AP), or automated insulin delivery (AID) system, represents a landmark achievement in the treatment of Type 1 Diabetes (T1D), transforming a once-disputed concept into the modern standard of care [1]. This technology aims to mimic the glucose-regulatory function of a healthy pancreas by automating insulin delivery. At its core, the artificial pancreas is a closed-loop control system that integrates continuous glucose monitoring with automated insulin infusion [2]. The development of these systems has been largely driven by advances in control algorithms, with Model Predictive Control (MPC) emerging as a predominant strategy due to its ability to handle system delays, constraints, and disturbances [3] [4]. This document details the core components of the AP system, analyzes the specific challenges in glucose control, and provides structured experimental protocols for evaluating MPC algorithms in both simulation and clinical settings, framed within the context of blood glucose regulation research.

System Components of the Artificial Pancreas

An artificial pancreas system is composed of three interconnected hardware components that work in concert with a control algorithm.

Core Components

- Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM): This sensor measures glucose concentrations in the interstitial fluid subcutaneously, transmitting data to the control algorithm nearly in real-time. Modern CGMs have been pivotal for AP development, though they introduce challenges such as a physiological time lag (typically 5-15 minutes) between blood and interstitial glucose levels and require periodic calibration [5].

- Control Algorithm: This is the "brain" of the AP system. Residing on a dedicated controller or a smartphone, the algorithm processes CGM data and determines the appropriate insulin infusion rate. Model Predictive Control (MPC) is particularly prominent because it uses a model of the patient's glucose-insulin dynamics to predict future glucose levels and computes optimal insulin deliveries while respecting safety constraints on insulin delivery and glucose levels [3] [4].

- Insulin Pump: This device delivers rapid-acting insulin subcutaneously based on commands from the control algorithm. Most systems use conventional pumps with infusion sets, while patch pumps that adhere directly to the skin are also available [5].

The Research Toolkit: Essential Components and Reagents

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for AP Development

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| In Silico Simulator | A computer model of the human metabolic system in T1D, accepted by regulatory bodies as a substitute for animal trials in early algorithm testing [1]. |

| Universal Research Platform (e.g., APS) | A software platform that enables automated communication between various CGMs, pumps, and control algorithms, powering early inpatient clinical trials [1]. |

| Rapid-Acting Insulin Analogue | The manipulated input in the control system; its pharmacodynamic variability and slow absorption kinetics are major challenges for controller design [5]. |

| Metabolic Challenge Meals | Standardized meals used in clinical trials to create a consistent and significant disturbance (glucose excursion) to evaluate controller performance [3]. |

| Continuous Glucose Monitor | Provides the primary feedback signal for the closed-loop system; its accuracy, delay, and reliability are critical for safe operation [5]. |

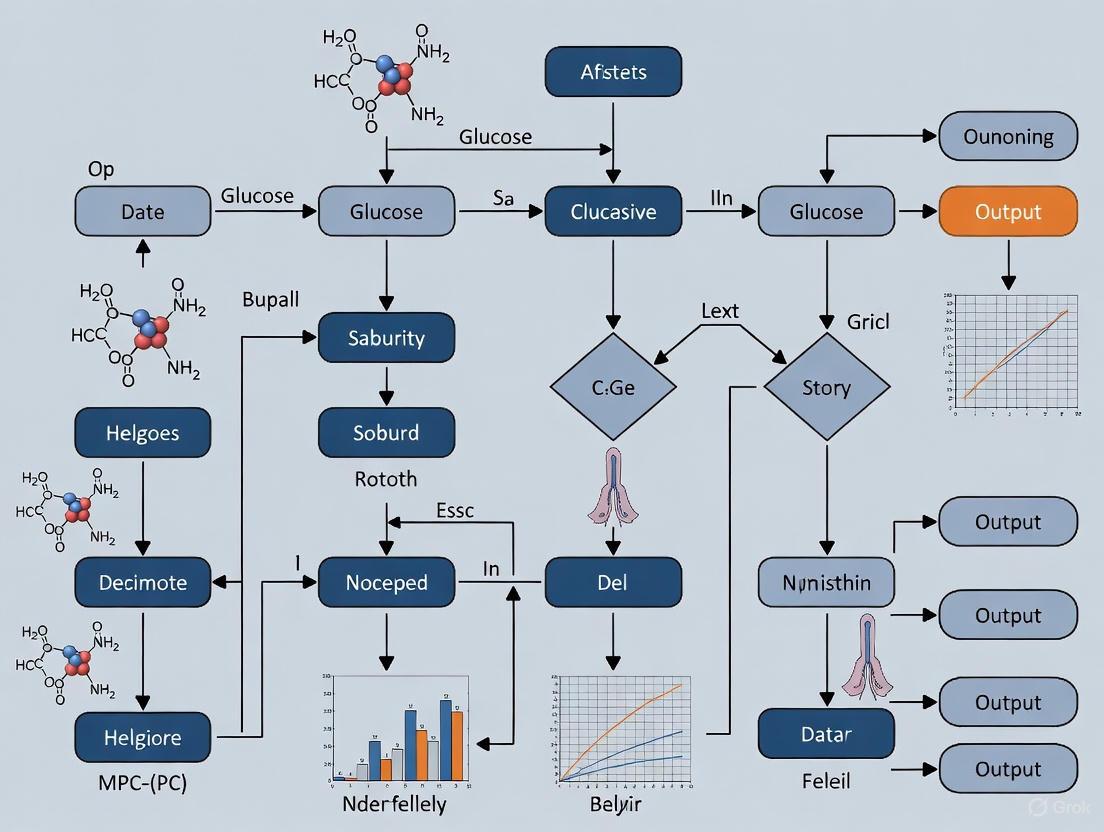

The interaction of these components forms a closed-loop control system, visually summarized in the workflow below.

Control Challenges and the Role of MPC

The primary challenge in closing the glucose control loop stems from the complex, nonlinear, and highly variable physiology of glucose-insulin dynamics. MPC has become a leading algorithmic approach due to its inherent ability to address several of these fundamental challenges.

Primary Control Challenges

- Significant Time Delays: The system is affected by multiple delays, including the slow absorption of subcutaneously administered insulin, the lag between blood and interstitial glucose measured by the CGM, and the delayed action of insulin on glucose uptake [5] [3].

- Meal Disturbances: Carbohydrate intake represents a large, rapid, and often uncertain disturbance. Accurately estimating the carbohydrate content of a meal is difficult, and the rate of glucose appearance in the blood is variable [5] [6].

- Inter- and Intra-Patient Variability: An individual's insulin sensitivity changes throughout the day and is influenced by factors like exercise, stress, and hormonal cycles. Furthermore, there is significant variability in insulin pharmacodynamics between different patients [5] [7].

- Actuator and Sensor Limitations: Insulin pumps can experience infusion set failures, while CGM sensors can suffer from signal dropouts or calibration errors, requiring the control algorithm to be robust to such device-related faults [5] [6].

- Safety Constraints: The controller must strictly avoid hypoglycemia while simultaneously minimizing hyperglycemia, creating a narrow therapeutic window for operation [8].

How MPC Addresses These Challenges

MPC is well-suited to this problem because it uses an internal model to predict future glucose trajectories over a defined horizon. This allows it to anticipate and proactively counteract glycemic events [3]. Key advantages include:

- Constraint Handling: MPC can explicitly incorporate constraints on maximum insulin delivery and minimum glucose levels, enhancing safety [3] [8].

- Delay Compensation: By forecasting future states, MPC can account for the system's inherent delays [3].

- Meal Announcement: MPC can effectively utilize feedforward action from meal announcements to improve postprandial control, though it must also handle unannounced meals robustly [3].

Quantitative Performance of MPC Algorithms

The effectiveness of MPC-based AID systems has been validated in numerous clinical trials. The table below summarizes key glycemic outcomes from a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Table 2: Glycemic Outcomes of MPC-based Artificial Pancreas vs. Conventional Therapy [4]

| Outcome Measure | Intervention Scenario | Mean Difference (MPC vs. Control) | Statistical Significance (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time in Target Range (3.9-10 mmol/L) | Overnight Use | +10.03% (95% CI: 7.50, 12.56) | < 0.00001 |

| Time in Hypoglycemia (< 3.9 mmol/L) | Overnight Use (Long-term: >1 month) | -1.34% (95% CI: -1.87, -0.81) | < 0.00001 |

Experimental Protocols for AP Research

Protocol 1: In Silico Closed-Loop Validation

This protocol uses a computer simulator to test and refine MPC algorithms prior to clinical studies [3].

- Objective: To assess the performance, robustness, and safety of a novel MPC algorithm under controlled conditions with a large virtual population.

- Materials:

- Simulator: FDA-accepted T1D simulation platform (e.g., UVa/Padova Simulator) [3].

- Algorithm: The MPC algorithm to be tested.

- Virtual Cohort: A population of

n(e.g., 100) adult, pediatric, and adolescent simulators with varying insulin sensitivities.

- Procedure:

- Day 1: Run a 24-hour simulation with a standard meal protocol (e.g., 45g breakfast, 70g lunch, 60g dinner) with 50% of meals announced to the algorithm.

- Day 2-4: Introduce realistic meal variations using a stochastic meal generator and include a period of moderate-intensity exercise (e.g., 45 minutes) on one day [9].

- Day 5: Test robustness by simulating a 30% over-estimation of carbohydrate content for all meals and a temporary CGM signal dropout.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate primary outcomes: Percentage of Time in Range (3.9-10.0 mmol/L), time in hypoglycemia (<3.9 mmol/L), and time in hyperglycemia (>10.0 mmol/L).

- Calculate secondary outcomes: Mean glucose, glucose standard deviation, and LBGI/HBGI (Low/High Blood Glucose Indices) [8].

The following diagram illustrates the iterative process of an in silico trial using MPC.

Protocol 2: Clinical Outpatient Trial

After successful in silico testing, the algorithm progresses to a clinical trial in a free-living environment.

- Objective: To evaluate the safety and efficacy of the MPC-based AP system in real-world conditions over an extended period.

- Materials:

- AID System: The integrated system comprising CGM, insulin pump, and handheld controller running the MPC algorithm.

- Study Cohort:

n(e.g., 30-50) adult participants with T1D. - Comparator: Sensor-augmented pump (SAP) therapy as the control intervention.

- Procedure:

- Design: Randomized, crossover trial where each participant undergoes both AID and control periods.

- Run-in Phase: A 1-2 week period where all participants use SAP therapy to collect baseline data and individualize pump settings.

- Intervention Phase: A 3-month period where the participant uses the MPC-based AID system. Users are instructed to announce meals but are not forced to, allowing for assessment of algorithm performance with unannounced meals.

- Control Phase: A 3-month period where the participant uses SAP therapy.

- Data Collection and Analysis:

Advanced MPC Formulations and Future Directions

Research continues to address the limitations of linear MPC. Recent advances explored in the literature include:

- Nonlinear Explicit MPC (NEMPC): This approach uses Taylor series expansion to create an analytical solution to the nonlinear MPC problem, significantly reducing computational burden and avoiding the need for iterative online optimization, which is beneficial for portable devices [8].

- Data-Driven and LSTM-Augmented MPC: To improve long-term prediction accuracy, studies are incorporating Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural networks to learn the nonlinear glucose dynamics from data. The predictor is structured to be affine in the future control inputs, allowing the MPC problem to remain a tractable quadratic program [9].

- Adaptive and Fault-Tolerant Control: Research into adaptive backstepping and other nonlinear methods aims to compensate for unannounced meals and actuator faults, providing robustness in cases of pump failures or mis-estimated meal sizes [6].

Model Predictive Control (MPC) is an advanced, model-based control strategy that uses a dynamic model of a system to predict its future behavior and compute optimal control actions through online optimization [10] [11]. Unlike reactive control strategies such as PID control, MPC operates on a proactive principle, anticipating future system behavior and disturbances to make informed decisions [10] [11]. This capability is particularly valuable for complex, multivariable systems with constraints, such as blood glucose regulation in artificial pancreas systems [12] [13].

The core architecture of MPC rests on three fundamental pillars: (1) a prediction model that forecasts system behavior, (2) an optimization process that computes control actions by minimizing a cost function, and (3) a receding horizon implementation that provides feedback and robustness [10] [11]. This architecture enables MPC to handle constraints directly, manage multivariable interactions, and compensate for delays—properties that make it exceptionally suitable for biomedical applications like glucose regulation [13].

In the context of blood glucose regulation for Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) patients, MPC has emerged as a leading control algorithm for artificial pancreas systems [12] [13]. Its predictive capability allows it to anticipate glycemic fluctuations and calculate appropriate insulin doses while respecting safety constraints on both insulin delivery and glucose concentrations [12]. This application note explores the core architectural components of MPC and their specific implementation in glucose regulation research.

Core Architectural Components of MPC

Prediction Models

The prediction model forms the foundation of any MPC implementation, serving as the mathematical representation of the system dynamics used to forecast future behavior [10] [11]. The choice of model significantly impacts the controller's performance, robustness, and computational requirements.

For discrete-time systems, which are common in digital control implementations including artificial pancreas systems, the state-space representation is typically used:

[ x{k+1} = f(xk, uk, pk) ] [ yk = h(xk, uk, pk) ]

Where (xk) represents the system states, (uk) the control inputs, (pk) the parameters, and (yk) the system outputs [11]. In glucose regulation applications, the states may include plasma glucose, subcutaneous glucose, insulin concentrations, and other physiological variables; the control input is typically insulin infusion rate; and the output is often the continuous glucose monitor (CGM) measurement [12] [13].

Table: Common Model Types in MPC for Glucose Regulation

| Model Type | Description | Advantages | Limitations | Representative Uses in Glucose Regulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological (Sorensen) | Comprehensive 19-state model representing organ-level glucose-insulin dynamics [13] | High physiological fidelity, accounts for glucagon | High complexity, computationally intensive | Dual-hormone (insulin & glucagon) control [13] |

| Compartmental (Hovorka) | 6-state nonlinear model with glucose compartments, insulin action, and plasma insulin [13] | Balanced complexity and accuracy, validated in clinical studies | Limited individualization | Single-hormone MPC implementations |

| Data-Driven (CHoKI) | Nonparametric learning method using patient data [12] | Customized per patient, no need for physiological model | Requires extensive training data | Learning-based MPC for inter-patient variability [12] |

| Minimal (Bergman) | 3-state model with plasma glucose, remote insulin, plasma insulin [13] | Simple structure, rapid computation | Limited accuracy, especially during meals | Early artificial pancreas prototypes |

For complex physiological systems like glucose metabolism, two main modeling approaches prevail: first-principles models derived from mass balance and physiological knowledge (e.g., Sorensen model), and data-driven models learned from patient data (e.g., CHoKI - Componentwise Hölder Kinky Inference) [12] [13]. The Sorensen model, with its 19 differential equations, offers comprehensive representation of glucose-insulin-glucagon dynamics but presents significant computational challenges [13]. In contrast, data-driven approaches like CHoKI create customized models for individual patients, potentially enhancing performance despite inter- and intra-patient variability in diabetes [12].

Optimization Framework

The optimization component is the computational engine of MPC, responsible for calculating control actions that minimize a defined cost function while satisfying operational constraints [10] [11]. The general finite-horizon optimal control problem solved at each sampling instant can be formulated as:

[ \min{\mathbf{u}{0:N}} J = \sum{k=0}^{N-1} l(xk, uk, pk) + m(xN) ] Subject to: [ x{k+1} = f(xk, uk, pk), \quad k = 0,\dots,N-1 ] [ u{lb} \leq uk \leq u{ub}, \quad k = 0,\dots,N-1 ] [ x{lb} \leq xk \leq x{ub}, \quad k = 0,\dots,N ] [ g(xk, u_k) \leq 0, \quad k = 0,\dots,N ]

Where (N) is the prediction horizon, (l(\cdot)) is the stage cost function, (m(\cdot)) is the terminal cost function, and the constraints represent input limits, state boundaries, and general nonlinear constraints [11].

In glucose regulation, the cost function typically penalizes deviations from the target glucose range (70-180 mg/dL) while minimizing excessive insulin delivery [12] [13]. For example:

[ J = \sum{k=1}^{N} wg(Gk - G{target})^2 + \sum{k=0}^{N-1} wI(Ik - I{basal})^2 ]

Where (Gk) is the predicted glucose level, (Ik) is the insulin infusion rate, and (wg), (wI) are weighting factors that balance the competing objectives of glucose control and insulin conservation [12].

Table: Optimization Considerations in Glucose Regulation MPC

| Aspect | Considerations in Glucose Regulation | Typical Values/Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Cost Function Terms | Glucose deviation from target, insulin delivery amount, constraint violation penalties | Quadratic terms for glucose error ((wg = 1.0)), smaller weights for insulin ((wI = 0.01)) [13] |

| Constraints | Hypoglycemia prevention (<70 mg/dL), hyperglycemia mitigation (>180 mg/dL), maximum insulin delivery, insulin on board (IOB) limits [12] | Hard constraints at 70 mg/dL and 250 mg/dL, IOB constraints based on patient-specific factors [12] |

| Optimization Algorithm | Computational efficiency, handling of nonlinearities, guarantee of feasible solution | Quadratic programming (linearized models), nonlinear programming (SQP, interior-point), explicit MPC [14] |

| Horizon Selection | Long enough to capture meal response, short enough for computational tractability | Prediction horizon: 2-6 hours; Control horizon: 30-120 minutes [12] |

A critical safety consideration in glucose regulation MPC is the incorporation of Insulin on Board (IOB) constraints [12]. These constraints dynamically limit insulin delivery based on previously administered insulin that remains active in the body, thereby reducing hypoglycemia risk:

[ uk \leq u{max} - IOB_k ]

Where (IOB_k) represents the estimated active insulin at time (k) [12]. This constraint prevents excessive insulin stacking, particularly following correction boluses or during periods of increasing insulin sensitivity.

Receding Horizon Principle

The receding horizon principle implements feedback in MPC and distinguishes it from traditional optimal control [10] [11]. This mechanism involves:

- At each sampling instant (k), measuring or estimating the current system state (x_k)

- Solving an optimization problem over a finite prediction horizon (N) to determine a sequence of optimal control moves (\mathbf{u}_{k:k+N-1}^*)

- Implementing only the first control action (u_k^*) from the optimized sequence

- Advancing to the next sampling instant (k+1), measuring the new state, and repeating the entire process

This "plan-and-execute-one-step" approach introduces feedback that compensates for model inaccuracies, measurement noise, and unmeasured disturbances [10]. In glucose regulation, this means the MPC can continuously adjust to unexpected glucose fluctuations, changes in insulin sensitivity, or unannounced meals [13].

The following diagram illustrates the receding horizon principle in the context of an artificial pancreas system:

Diagram: Receding Horizon Principle in Artificial Pancreas

The selection of appropriate horizons represents a critical design trade-off. The prediction horizon must be sufficiently long to capture the dominant dynamics—typically 2-6 hours in glucose regulation to account for meal responses and insulin pharmacokinetics [12]. The control horizon is often shorter (30-120 minutes) to reduce computational complexity while maintaining adequate degrees of freedom [10]. The sampling time (typically 5-10 minutes) balances responsiveness to rapid glucose changes with computational burden and CGM measurement frequency [13].

MPC Implementation Protocols for Glucose Regulation

Experimental Setup and Reagent Solutions

Robust experimental protocols are essential for developing and validating MPC systems for glucose regulation. The following table details key research components and their functions:

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Glucose Regulation MPC

| Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| In Silico Simulator | Provides validated virtual patient population for testing and development | UVA/Padova T1D Simulator (FDA-accepted substitute for preclinical trials) [12] |

| Physiological Model | Represents glucose-insulin dynamics for prediction | Sorensen Model (19 states), Hovorka Model (6 states), Bergman Minimal Model (3 states) [13] |

| Learning Method | Customizes controller to individual patient characteristics | Componentwise Hölder Kinky Inference (CHoKI) - nonparametric learning [12] |

| Performance Metrics | Quantifies controller efficacy and safety | Time-in-Range (70-180 mg/dL), Time-in-Hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL), Time-in-Hyperglycemia (>180 mg/dL) [12] |

| Constraint Formulation | Ensures patient safety despite disturbances | Insulin-on-Board (IOB) constraints, maximum basal rate limits, hypoglycemia prediction constraints [12] |

The UVA/Padova simulator has emerged as a critical tool in artificial pancreas research, providing a population of virtual T1D patients with realistic physiological variability [12]. This simulator enables controlled, reproducible testing of MPC algorithms without risking patient safety, and its FDA acceptance for preclinical studies underscores its validity [12].

Detailed Protocol: CHoKI-Based MPC Implementation

The following protocol outlines the implementation procedure for a data-driven MPC using the CHoKI learning method, as presented in recent research [12]:

Objective: Implement a personalized MPC for basal insulin delivery in T1D patients that maintains blood glucose in the safe range (70-180 mg/dL) while minimizing hypoglycemia risk through IOB constraints.

Materials:

- UVA/Padova T1D Simulator (10 adult patients)

- Historical data collection: CGM measurements, insulin delivery records, meal announcements (if available)

- MATLAB/Python implementation environment with optimization toolbox

- CHoKI learning method code implementation

Procedure:

Data Collection Phase (2 weeks per virtual patient):

- Collect CGM measurements at 5-minute intervals

- Record basal insulin delivery rates

- Log meal carbohydrate content and timing (if available)

- Include various daily patterns to capture inter-day variability

Model Identification Phase:

- Apply CHoKI nonparametric learning to historical data

- Identify input-output relationship: ( G{k+1} = f(Gk, G{k-1}, ..., Ik, I_{k-1}, ...) )

- Validate model prediction accuracy on withheld data (10% of dataset)

- Require minimum prediction accuracy: CVGA A/B zone > 90%

MPC Configuration:

- Prediction horizon: 3 hours (N = 36 steps at 5-minute intervals)

- Control horizon: 1 hour (M = 12 steps)

- Cost function weights: ( wg = 1.0 ) (glucose error), ( wI = 0.01 ) (insulin change)

- Safety constraints:

- Hard glucose constraint: 70 mg/dL (lower bound)

- IOB-dependent insulin constraint: ( uk \leq u{max} - IOB_k )

- Maximum basal rate: patient-specific based on total daily dose

Closed-Loop Evaluation:

- Implement 7-day in-silico trial for each virtual patient

- Include unannounced meals (50% of meals) to test robustness

- Introduce ±30% insulin sensitivity variations to test adaptation

- Compare against standard constant basal therapy (control)

Performance Analysis:

- Calculate percentage time in target range (70-180 mg/dL)

- Quantify time in hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL) and hyperglycemia (>180 mg/dL)

- Compute average glucose and glucose variability (coefficient of variation)

- Perform statistical analysis (paired t-tests) against control condition

The following workflow diagram illustrates the CHoKI-based MPC development process:

Diagram: CHoKI-Based MPC Development Workflow

Performance Metrics and Validation

Rigorous performance validation is essential for evaluating glucose regulation MPC. Recent studies have demonstrated promising results with the CHoKI-based approach:

Table: Quantitative Performance of CHoKI-MPC in Glucose Regulation

| Metric | Standard Basal Therapy | CHoKI-MPC | Improvement | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time-in-Range (70-180 mg/dL) | 65.2% | 78.9% | +13.7% | 7-day in-silico trial (n=10 adults) [12] |

| Time-in-Hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL) | 4.8% | 1.2% | -3.6% (75% reduction) | UVA/Padova simulator [12] |

| Time-in-Hyperglycemia (>180 mg/dL) | 30.0% | 19.9% | -10.1% | With ±30% insulin sensitivity variation [12] |

| Average Tracking Error | 14.3 mg/dL | 4.4 mg/dL | -9.9 mg/dL | Compared to setpoint of 90 mg/dL [13] |

The significant reduction in hypoglycemia time (75% reduction) demonstrates the particular strength of MPC with IOB constraints in mitigating the most acute safety risk in glucose regulation [12]. The improved time-in-range (+13.7%) while simultaneously reducing hyperglycemia confirms the multi-objective optimization capability of MPC [12].

Advanced MPC Architectures for Enhanced Robustness

Multi-Stage MPC for Uncertainty Management

Multi-stage MPC extends the basic architecture to explicitly handle system uncertainties through a scenario-tree formulation [11]. This approach is particularly valuable in glucose regulation due to significant inter- and intra-patient variability in insulin sensitivity and meal responses.

The multi-stage approach:

- Approximates the uncertainty space with discrete samples

- Constructs a tree of possible future scenarios

- Optimizes control actions that are feasible for all considered scenarios

- Incorporates feedback information through non-anticipativity constraints

For a system with (np) uncertain parameters and (vi) possible values for each parameter, the number of scenarios grows as (Ns = (\prod{i=1}^{np} vi)^{N{robust}}) [11]. To maintain computational tractability, branching is typically limited to a robust horizon ((N{robust})) shorter than the prediction horizon.

In glucose regulation applications, key uncertainties include:

- Meal absorption rates and timing

- Insulin sensitivity variations

- Physical activity effects

- Stress and illness impacts

Hybrid MPC for Dual-Hormone Control

Advanced artificial pancreas systems may employ dual-hormone control using both insulin (to lower glucose) and glucagon (to raise glucose) [13]. This requires hybrid MPC architectures capable of managing multiple manipulated variables with different constraints and dynamics.

The MPC formulation for dual-hormone control extends the cost function:

[ J = \sum{k=1}^{N} wg(Gk - G{target})^2 + \sum{k=0}^{N-1} [wI(Ik - I{basal})^2 + w{GL}(GLk)^2] ]

Where (GL_k) represents glucagon delivery, with appropriate constraints on both hormone delivery rates [13]. The Sorensen model, with its explicit representation of glucagon dynamics, is particularly suited for such applications [13].

The core architecture of Model Predictive Control—encompassing prediction models, optimization, and receding horizon implementation—provides a powerful framework for blood glucose regulation in artificial pancreas systems. The predictive capability enables anticipation of glycemic fluctuations, while the optimization framework permits explicit handling of safety constraints and competing control objectives.

The integration of data-driven learning methods like CHoKI with traditional MPC represents a promising direction for personalized glucose control, adapting to individual patient characteristics and varying insulin sensitivity [12]. Furthermore, robust MPC formulations, such as multi-stage approaches, enhance safety despite significant uncertainties in meal absorption, metabolism, and daily activities.

For researchers and drug development professionals, implementing the protocols and architectures described herein requires careful attention to model selection, constraint formulation, and validation methodologies. The use of FDA-accepted simulation platforms like the UVA/Padova simulator provides a critical foundation for preclinical development, while rigorous performance metrics ensure meaningful evaluation of controller efficacy and safety.

As artificial pancreas technology evolves, MPC continues to offer a flexible, robust control paradigm capable of incorporating increasingly sophisticated physiological models, adaptive learning mechanisms, and enhanced safety constraints—ultimately improving the quality of life for individuals with Type 1 Diabetes.

Model Predictive Control (MPC) algorithms represent a significant evolution in automated insulin delivery (AiDS) for blood glucose regulation, directly addressing two persistent challenges in conventional diabetes therapy: high glycemic variability and postprandial hyperglycemia. Conventional methods, such as multiple daily injections (MDI) or traditional insulin pump therapy, often rely on predefined, static insulin regimens. These approaches struggle to adapt to dynamic physiological conditions, leading to suboptimal glucose control, particularly after meals. MPC, a advanced model-based control strategy, utilizes a dynamic model of the patient's glucose-insulin metabolism to predict future glucose levels and proactively compute optimal insulin doses. This enables the system to manage glycemic variability and respond to unannounced meals more effectively than reactive conventional therapies. This document details the quantitative advantages, experimental protocols, and core components of MPC-based systems for researchers and drug development professionals.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of MPC-based Systems vs. Conventional Therapy

| Metric | Conventional Therapy (Typical Performance) | MPC-based AiDS (Reported Performance) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Time in Range (TIR: 70-180 mg/dL) | ~60-65% (varies widely) | 75.97% - 91.08% (in-silico) / 83.4% (preclinical) | [15] [16] |

| Time in Hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL) | ~3-5% | 0.0% - 3.62% (mild events, no severe hypoglycemia) | [17] [16] |

| Mean Blood Glucose Level | Often >154 mg/dL | 132 - 159 mg/dL | [18] |

| Postprandial Hyperglycemia Control | Frequent excursions | Rapid regulation (e.g., peak of 320 mg/dL regulated within 50 min) | [16] |

| Performance with Unannounced Meals | Poor without manual bolus | Maintains TIR >83% via meal detection and adaptive control | [18] [16] |

Core MPC Algorithm Components and Workflow

The efficacy of MPC in managing glycemic variability stems from its structured, multi-component architecture. The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of a modern MPC system for an AiDS.

Diagram 1: Integrated MPC Workflow for AiDS. The system uses a model to predict future glucose levels and an optimizer to compute insulin doses, enhanced by meal detection and state estimation.

Key Component Functions

- Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM): Provides real-time, noisy glucose measurements to the controller [15] [19].

- State & Disturbance Estimator: A Kalman filter is typically used to reduce sensor noise and provide an optimal estimate of the current metabolic state (e.g., glucose levels, insulin on board) and unmeasured disturbances, which is critical for the controller's accuracy [18] [15].

- Glucose-Insulin Model: A mathematical model (e.g., based on the Bergman minimal model or identified from population data) that predicts future glucose trajectories over a defined horizon based on the current state and potential insulin inputs [6] [15] [19].

- MPC Optimizer: The core algorithm that solves a constrained optimization problem at each control cycle. It calculates the sequence of insulin doses that minimizes a cost function (penalizing hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, and excessive insulin use) over the prediction horizon, subject to safety constraints [19].

- Meal Detection Algorithm: A supervisory module that analyzes the rate of change of CGM readings to detect unannounced meals and trigger a feed-forward bolus or adjust controller aggressiveness [18].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In-Silico Validation of Adaptive MPC with RLS Estimation

This protocol evaluates the enhancement of MPC through real-time parameter adaptation [15].

1. Objective: To determine if integrating a Recursive Least Squares (RLS) estimator for insulin sensitivity (( \theta_1 )) improves glycemic regulation and if an event-triggered (ET) MPC strategy reduces energy consumption.

2. Materials & Setup:

- Simulator: UVA/Padova T1DM Simulator (FDA-approved) with 10 virtual adult subjects.

- Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL): Raspberry Pi 3B, integrated with a custom low-cost insulin pump and battery driver.

- Control Strategies:

- Time-Triggered (TT-MPC): Standard MPC with 5-minute control cycles.

- TT-MPC with RLS: Enhanced with RLS for real-time ( \theta_1 ) estimation.

- Event-Triggered MPC (ET-MPC): Control actions computed only when a triggering condition (e.g., predicted glucose deviation) is met.

3. Procedure:

- Model Identification: Identify the prediction model (Eq. 1 in [15]) from the 10 adult subjects in the simulator.

- Controller Tuning: Tune the MPC and RLS parameters (forgetting factor, initial covariance).

- HIL Emulation: Run three-day simulations for each control strategy. Introduce unannounced carbohydrate meals and realistic CGM noise (Eq. 2 in [15]).

- Data Collection: Record Time in Range (TIR), hypoglycemia events, total insulin delivered, and energy consumption of the HIL setup.

4. Key Analysis & Outcomes:

- Glycemic Control: Compare TIR and hypoglycemia events between TT-MPC and TT-MPC+RLS.

- Energy Efficiency: Compare the number of control actions and total energy consumption between TT-MPC and ET-MPC.

- Conclusion: The study confirmed that RLS integration significantly improved TIR. The ET strategy reduced control actions by up to 60%, extending device operational time threefold with minimal performance loss [15].

Protocol 2: Preclinical Validation of Offset-Free Zone MPC in a Diabetic Rat Model

This protocol outlines the in vivo validation of an MPC algorithm, a critical step before human trials [16].

1. Objective: To validate the safety and efficacy of an impulsive, offset-free zone MPC (OF-ZMPC) in managing unannounced meals and plant-model mismatch in a live animal model.

2. Materials & Setup:

- Subjects: 14 male Wistar rats with streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetes.

- Devices: Commercial CGM sensor and a customized, low-cost insulin pump.

- Controller: OF-ZMPC, which uses a disturbance model to eliminate steady-state error.

3. Procedure:

- Day 0 - Induction & Device Installation: Induce diabetes via STZ. After stabilization, surgically implant the CGM and connect the insulin pump.

- Day 1 - Parameter Estimation:

- Administer a manual insulin bolus via the pump.

- Record the glucose response with the CGM.

- Perform off-line parameter estimation for the rat-specific glucose-insulin model.

- Day 2 - Controller Tuning:

- Use the estimated parameters to perform simulations for initial tuning of the OF-ZMPC and its state estimator.

- Conduct short in vivo tests to fine-tune controller parameters.

- Day 3-5 - Autonomous Trial:

- Initiate a 72-hour continuous, closed-loop operation of the i-AiDS.

- Provide food ad libitum (unannounced to the controller).

- Monitor and record glucose levels, insulin delivery, and animal health (e.g., body weight).

4. Key Analysis & Outcomes:

- Primary Endpoint: Percent Time in Range (80-180 mg/dL).

- Safety Metrics: Number of hypoglycemic events (<70 mg/dL) and severe hyperglycemic events.

- Model Fidelity: Median Absolute Relative Difference (MARD) between model predictions and CGM data.

- Conclusion: The controller achieved 83.4% TIR with no severe hypoglycemia, effectively handling unannounced meals and plant-model mismatch (MARD 24.66%), demonstrating robust preclinical performance [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for AiDS Research

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Citation |

|---|---|---|

| UVA/Padova T1DM Simulator | FDA-approved simulation platform for in-silico testing and validation of control algorithms without initial animal use. | [15] [16] |

| Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL) Platform | Embedded system (e.g., Raspberry Pi) used to test control algorithms in a realistic hardware environment, measuring computational load and energy consumption. | [15] |

| Recursive Least Squares (RLS) Estimator | An adaptive algorithm used to estimate critical, time-varying patient parameters (e.g., insulin sensitivity) in real-time, improving controller personalization. | [15] |

| Offset-Free MPC Framework | An MPC formulation that incorporates a disturbance model to eliminate steady-state glucose errors caused by plant-model mismatch. | [16] |

| Meal Detection & Size Estimation Algorithm | A feed-forward component that identifies the occurrence and approximate carbohydrate content of unannounced meals, allowing for corrective bolusing. | [18] |

| Neural Network (NN) for MPC | A method to replicate complex MPC behavior using a lightweight, easy-to-deploy neural network, enabling implementation on resource-constrained devices. | [19] |

| Insulin-on-Board (IOB) Constraints | Safety constraints within the MPC optimizer that account for the active insulin from previous doses to prevent stacking and hypoglycemia. | [18] |

Advanced MPC Architecture: Meal Detection and IOB Safety

A critical advantage of MPC lies in its integration of safety modules and feed-forward mechanisms. The following diagram details the logic of the meal detection and IOB safety supervision system.

Diagram 2: Meal Detection and Safety Supervision Logic. This supervisory layer enhances the core MPC by adding feed-forward meal compensation and critical safety shut-offs to mitigate hypoglycemia risk.

The development of effective Model Predictive Control (MPC) algorithms for automated blood glucose regulation requires confronting significant physiological challenges that disrupt glucose homeostasis. Meal disturbances, physical activity, psychological and physical stress, and substantial inter-patient variability represent core obstacles that can compromise the performance and safety of artificial pancreas systems [3] [9]. This document details these challenges and provides structured experimental protocols to facilitate their systematic investigation, enabling the development of more robust, adaptive MPC frameworks capable of maintaining glycemic control amidst real-world variability.

Meal Disturbances

Physiological Impact and Quantitative Effects

Carbohydrate intake represents one of the most significant postprandial glycemic disturbances. The concept of Glycemic Load (GL) quantifies the glycemic impact of a meal by considering both the quality (Glycemic Index) and quantity of carbohydrates. A controlled study investigating the effects of high and low GL meals on individuals with different Body Mass Index (BMI) revealed critical data for modeling postprandial glucose dynamics [20].

Table 1: Blood Glucose Response to High vs. Low Glycemic Load Meals [20]

| BMI Group | Meal Type | Energy (kcal) | Peak BG Increase (Time) | BG Stability | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (BMI 18.5-24.9) | High GL (≥20) | 482 kcal | Significant at 60 min | Less Stable | < 0.05 |

| Normal (BMI 18.5-24.9) | Low GL (≤10) | 483 kcal | Lower increase | More Stable | < 0.05 |

| Overweight (BMI 25.0-29.9) | High GL (≥20) | 482 kcal | Significant at 90-120 min | Less Stable | < 0.05 |

| Overweight (BMI 25.0-29.9) | Low GL (≤10) | 483 kcal | Lower increase | More Stable | < 0.05 |

The study demonstrated that high GL meals produce a more pronounced and prolonged blood glucose elevation, particularly in overweight individuals, highlighting the interaction between meal composition and metabolic phenotype [20]. Furthermore, meal timing relative to circadian rhythms significantly influences glycemic control. Research shows that late-evening meals coinciding with elevated melatonin levels impair insulin secretion and glucose control, an effect exacerbated in carriers of the MTNR1B gene variant [21].

Experimental Protocol: Meal Challenge Studies

Objective: To characterize individual postprandial glycemic responses to standardized meals for personalizing MPC model parameters.

Methodology:

- Subject Preparation: Recruit subjects spanning different glycaemic statuses (normal, prediabetic, type 1 and type 2 diabetic). Instruct subjects to fast for 10-12 hours overnight.

- Test Meals: Prepare isocaloric meals (providing 25% of estimated daily energy requirement) with low (≤10) and high (≥20) Glycemic Load. Macronutrient composition should be standardized: Low GL meal (66% CHO, 17% protein, 17% fat); High GL meal (60% CHO, 10% protein, 30% fat) [20].

- Blood Sampling: Insert an intravenous catheter for frequent sampling. Collect baseline (0 min) capillary or venous blood samples. Administer the test meal and ensure consumption within 15 minutes. Collect subsequent blood samples at 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 minutes postprandial [20].

- Meal Timing Studies: For chronobiology studies, conduct identical protocols with early dinner (≥4 hours before bedtime) and late dinner (close to bedtime) conditions, measuring concomitant melatonin levels [21].

- Data Analysis: Plot glucose-time curves and calculate area under the curve (AUC). Model the glucose rise kinetics and identify time-to-peak for each subject group.

Exercise

Physiological Impact and Quantitative Effects

Physical activity influences glucose homeostasis through multiple, intensity-dependent mechanisms. Exercise enhances insulin sensitivity and stimulates insulin-independent glucose uptake via muscle contractions [22]. The effects, however, vary significantly with exercise modality and duration.

Table 2: Blood Glucose Responses to Different Exercise Modalities

| Exercise Modality | Intensity | Duration | Acute BG Effect (During) | BG Effect (Post-Exercise) | Key Physiological Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Aerobic | Moderate (50-70% HRmax) | 30-60 min | Gradual decrease [22] | Increased insulin sensitivity for 24-72 hours [22] [23] | Increased GLUT4 translocation, enhanced insulin signaling [23] |

| High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) | Vigorous (≥80% VO₂max) | Brief bursts (e.g., 30s sprints) | Increase or stability [23] | Improved BG control for 24 hours (T2D) [23] | Catecholamine-driven hepatic glucose production, significant glycogen depletion [23] |

| Resistance Training | Variable | 60 min | Potential increase [24] | Improved long-term glycemic control (HbA1c) | Muscle mass development, transient hormonal responses |

High-Intensity Exercise (HIE) requires special consideration in MPC design. While it can cause transient hyperglycemia during and immediately after activity, it significantly improves glucose control for 24-72 hours post-exercise and carries a lower immediate risk of hypoglycemia compared to moderate-intensity exercise [23].

Experimental Protocol: Exercise Challenge Studies

Objective: To quantify the impact of various exercise modalities on glucose dynamics to inform disturbance models in MPC.

Methodology:

- Subject Preparation: Recruit subjects with diabetes (type 1 and type 2). Standardize meal timing and insulin administration prior to testing.

- Pre-Exercise Assessment: Check blood glucose 15-30 minutes before exercise. Do not exercise if BG >270 mg/dL with ketosis or <90 mg/dL; instead, administer 15-30g carbohydrates for low BG [24].

- Exercise Protocols:

- Moderate Aerobic: Cycle ergometry at 60-70% of maximum heart rate for 45 minutes.

- High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT): Perform 4-6 cycles of 30-second "all-out" Wingate sprints on a cycle ergometer, separated by 4 minutes of rest [23].

- Resistance Training: Conduct a circuit of 8 exercises (e.g., leg press, chest press), 3 sets of 8-12 repetitions at 70-80% of one-repetition maximum.

- Monitoring: Measure blood glucose immediately before, every 15-30 minutes during, immediately after, and then hourly for 6-12 hours post-exercise. Use continuous glucose monitors (CGM) for dense data capture [24].

- Safety Measures: Have fast-acting carbohydrates (glucose tablets, juice) available to treat hypoglycemia (BG <70 mg/dL). Follow the 15-15 rule: consume 15g carbohydrates, wait 15 minutes, and recheck BG [22].

Figure 1: Exercise-Mediated Glucose Regulation Pathway

Stress

Physiological Impact and Quantitative Effects

Stress-Induced Hyperglycemia (SIH) is a common phenomenon in critically ill patients and during psychological stress, driven by neuroendocrine activation. SIH is defined as blood glucose >180 mg/dL in individuals without pre-existing diabetes and is associated with increased mortality, longer hospital stays, and higher complication rates [25].

The underlying pathophysiology involves two major systems:

- The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis: Activation leads to increased cortisol secretion, which promotes gluconeogenesis and induces insulin resistance in peripheral tissues [26] [25].

- The Sympathoadrenal System: Releases catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine), which further stimulate glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis while suppressing insulin secretion [26].

Chronic stress perpetuates a vicious cycle of insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction, significantly increasing the risk for developing type 2 diabetes [26]. Counter-regulatory hormones and pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) work in concert to disturb glucose homeostasis by impairing insulin signaling and GLUT-4 translocation [25].

Experimental Protocol: Characterizing Stress-Induced Hyperglycemia

Objective: To quantify the glycemic and metabolic response to physiologic stress for integration into MPC stress models.

Methodology:

- Study Population: Include critically ill patients (e.g., post-cardiac surgery, severe infection) and/or healthy subjects under controlled psychological stress tests.

- Biomarker Assessment: On admission and at 24-hour intervals, collect blood samples for:

- Glucose (point-of-care and central lab)

- Counter-regulatory hormones: Cortisol, Catecholamines

- Inflammatory cytokines: IL-6, TNF-α

- Monitoring: Implement continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) or frequent capillary glucose checks (e.g., every 4-6 hours) to assess glycemic variability and identify hyperglycemic episodes [25].

- Insulin Sensitivity Assessment: Use validated methods like the Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) or hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps in research settings to quantify insulin resistance.

- Data Correlation: Statistically correlate the magnitude and duration of hyperglycemia with the levels of stress biomarkers and clinical outcomes (e.g., length of stay, infection rates).

Figure 2: Stress-Induced Hyperglycemia Pathway

Inter-patient Variability

Inter-patient variability presents a fundamental challenge for "one-size-fits-all" MPC algorithms. This variability stems from a complex interplay of factors:

- Genetic Factors: Gene variants, such as the G-allele in the melatonin receptor-1b gene (MTNR1B), significantly affect glycemic responses to meal timing [21].

- Diabetes Type and Pathophysiology: Type 1 diabetes is characterized by absolute insulin deficiency, whereas type 2 diabetes is defined by insulin resistance and progressive β-cell dysfunction [26].

- Clinical Phenotype: Factors such as BMI, body composition, duration of diabetes, presence of diabetes-related complications, and beta-cell reserve capacity contribute to significant differences in insulin sensitivity and carbohydrate metabolism [20].

- Drug Therapies: Different medications (e.g., metformin, sulfonylureas, insulin) profoundly alter underlying physiology and glycemic responses [26].

The performance of personalized dosing strategies compared to clinician management is shown in the GLUCOSE study, where a distributional reinforcement learning algorithm achieved significantly higher Time in Range (TIR) when its recommendations were followed [27].

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Inter-patient Variability

Objective: To identify key sources of inter-patient variability and create patient stratification strategies for personalized MPC.

Methodology:

- Comprehensive Phenotyping:

- Clinical: Document age, sex, BMI, diabetes type and duration, body composition (DEXA scan).

- Metabolic: Perform Oral Glucose Tolerance Tests (OGTT) and hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps to measure insulin sensitivity and secretion.

- Genetic: Sequence or genotype known variants associated with glycemic control (e.g., MTNR1B [21]).

- Lifestyle: Assess dietary patterns, physical activity levels, and sleep-wake cycles.

- Cluster Analysis: Use unsupervised machine learning (e.g., k-means clustering) on the phenotyping data to identify distinct subgroups of patients with similar physiological profiles.

- Model Personalization: For each cluster, identify individualized model parameters for MPC algorithms. Techniques may include Bayesian estimation or transfer learning to adapt a base model to individual patient data.

- In-silico Validation: Use a validated simulation platform (e.g., the UVA/Padova T1D Simulator) populated with virtual patients representing the identified clusters to test the robustness of MPC algorithms [3] [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Glucose Regulation Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) | Provides real-time, interstitial glucose readings at 1-5 minute intervals. | Dense glucose monitoring during meal, exercise, and stress challenges [27]. |

| Glucometer & Test Strips | Provides point-of-care capillary blood glucose measurements. | Calibration of CGM; backup glucose measurement during exercise [20] [24]. |

| Intravenous Insulin Infusion System | Precisely delivers regular insulin under controlled rates. | Implementation of MPC-derived insulin doses in closed-loop studies [3] [9]. |

| ELISA Kits (Cortisol, Catecholamines, Cytokines) | Quantifies specific biomarkers in serum/plasma. | Measuring stress hormones (cortisol, epinephrine) and inflammatory markers (IL-6, TNF-α) [26] [25]. |

| Standardized Meal Tests | Provides a consistent nutritional challenge to assess postprandial glucose metabolism. | Meal challenge studies with defined macronutrient composition and Glycemic Load [20]. |

| Cycle Ergometer / Treadmill | Provides a standardized and quantifiable exercise workload. | Conducting aerobic and high-intensity interval exercise protocols [23]. |

| Hyperinsulinemic-Euglycemic Clamp Equipment | The gold-standard method for quantifying insulin sensitivity in vivo. | Detailed metabolic phenotyping for inter-patient variability studies. |

| In-silico Patient Simulator | A computer model of the glucose-insulin system for testing algorithms. | Pre-clinical validation of MPC algorithms in a virtual population before human trials [3]. |

Addressing the physiological challenges of meal disturbances, exercise, stress, and inter-patient variability is paramount for the advancement of MPC in blood glucose regulation. The experimental protocols and data outlined herein provide a framework for systematically quantifying these disturbances and incorporating them into adaptive, personalized control models. Future research should focus on integrating real-time detection of these states (e.g., exercise, stress) and developing MPC frameworks that can automatically adapt to an individual's unique and dynamic physiology.

The global diabetes epidemic represents one of the most significant public health challenges of the 21st century, creating an urgent clinical imperative for advanced management strategies. For researchers developing blood glucose regulation algorithms, understanding the scale of this burden and the specific challenges in achieving glycemic control is fundamental. The growing prevalence of diabetes worldwide, coupled with persistent issues in treatment adherence and glucose management, provides a powerful justification for technological innovations such as model predictive control (MPC) systems. This application note synthesizes the most current global statistics on diabetes prevalence and analyzes the factors contributing to suboptimal glycemic control, with particular relevance to the development of automated insulin delivery systems.

Global Diabetes Burden: Quantitative Analysis

Current Prevalence and Projections

The global diabetes burden has reached alarming proportions, with recent estimates indicating a rapid acceleration in prevalence across both developed and developing nations. The data reveals a consistent upward trajectory that shows no signs of abating without significant intervention.

Table 1: Global Diabetes Prevalence Estimates and Projections

| Metric | 1995 | 2024/2025 | 2050 | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Adult Prevalence | 4.0% [28] | 11.1% (1 in 9 adults) [29] | 12.2% (1 in 8 adults) [29] | IDF Diabetes Atlas |

| Total Cases (Adults) | 135 million [28] | 589-590 million [29] | 853 million [29] | IDF Diabetes Atlas |

| Type 1 Diabetes Cases | - | 9.5 million (2025) [30] | 14.7 million (2040 projection) [30] | IDF/T1D Index |

| Undiagnosed Cases | - | 252 million (4 in 10 adults) [29] | - | IDF Diabetes Atlas |

The historical context reveals the dramatic scale of this increase, with global adult diabetes prevalence rising from 7% to 14% between 1990 and 2022—a doubling within just three decades [31]. This trend is particularly pronounced in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where 81% of people with diabetes now reside [29]. The analysis of untreated diabetes reveals even starker disparities, with approximately 450 million adults (59% of all cases) remaining untreated in 2022, 90% of whom live in LMICs [31].

Regional Variations and Risk Factors

The distribution of diabetes burden demonstrates significant geographical heterogeneity, with important implications for targeted intervention strategies. The WHO South-East Asia and Eastern Mediterranean Regions report the highest prevalence rates at approximately 20% among adults [31]. Type 2 diabetes, which constitutes over 90% of all cases, is driven by complex interactions between multiple factors including urbanization, aging populations, decreasing physical activity, and increasing overweight and obesity prevalence [29]. The structural determinants include socioeconomic transitions, marketing of unhealthy foods, and economic hardships that create barriers to healthy lifestyle choices [31].

Suboptimal Glycemic Control: Measurement and Contributing Factors

The Scope of Insulin Dosing Irregularities

For researchers developing MPC algorithms, understanding the very specific failures in current insulin administration protocols provides critical insight into the clinical problems requiring technological solutions. Recent empirical evidence demonstrates that suboptimal insulin dosing represents a significant barrier to glycemic control.

Table 2: Insulin Dosing Irregularities Among People with Diabetes (30-Day Recall)

| Dosing Irregularity | Basal Insulin | Bolus Insulin | Reported By |

|---|---|---|---|

| Missed Doses | 47.3% of patients (mean 3.5 ± 2.9 doses) [32] | 58.0% of patients (mean 5.0 ± 10.1 doses) [32] | Patient Report |

| Mistimed Doses | 47.3% of patients (mean 3.9 ± 4.3 doses) [32] | 51.0% of patients (mean 5.0 ± 7.1 doses) [32] | Patient Report |

| Miscalculated Doses | 47.5% of patients (mean 4.5 ± 5.0 doses) [32] | 63.3% of patients (mean 5.5 ± 7.5 doses) [32] | Patient Report |

This data from a 2025 study of German patients using analogue insulin pens reveals that nearly half of all patients experience significant deviations from their prescribed insulin regimens across multiple dimensions [32]. Healthcare professionals corroborate these findings, with ≥67% indicating that up to 30% of their patients miss, forget, skip, mistime, or miscalculate insulin doses within a 30-day period [32].

Underlying Causes and Consequences

The reasons for these dosing irregularities are multifaceted, including forgetting doses, disruptions to normal routines, being too busy or distracted, and uncertainty about appropriate dosing amounts [32]. These adherence challenges contribute directly to failure to achieve glycemic targets, with studies showing that over half of German type 2 diabetes patients fail to attain their HbA1c goals [32]. The consequences extend beyond suboptimal glucose control to include increased risks of hypoglycemia, heightened healthcare costs, and potentially all-cause mortality [32].

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Insulin Dosing Behaviors

Study Design and Methodology

To systematically investigate the scope and nature of insulin dosing irregularities, researchers can employ the following protocol adapted from contemporary studies in this domain:

Objective: To quantify the prevalence, frequency, and underlying reasons for suboptimal insulin dosing behaviors among people with diabetes using insulin pen devices.

Participant Recruitment:

- Target Population: 400 adults with diabetes (Type 1: n=100; Type 2: n=300) using analogue insulin pens

- Inclusion Criteria: Age ≥18 years; clinician-confirmed T1D or T2D diagnosis; current use of analogue insulin pens (basal-only or basal-bolus regimens)

- Exclusion Criteria: Current use of connection-enabled pen systems, caps, or sleeves

- Recruitment Quotas: Apply soft quotas for HbA1c levels (<7%: ≤25%; unknown HbA1c: ≤25%; recent diagnosis <6 months: ≤25%; pen use <6 months: ≤25%) to enhance generalizability

Healthcare Professional Cohort:

- Sample: 160 HCPs (general practitioners: n=80; specialists: n=80)

- Inclusion Criteria: ≥2 years experience; currently prescribing insulin for adults using insulin pens; actively seeing ≥5 such patients weekly

Assessment Instrument:

- Implement a 58-item questionnaire for people with diabetes and 53-item questionnaire for HCPs

- Develop questions through systematic literature review and consultation with diabetes advocates and key opinion leaders

- Pilot testing using virtual web-assisted telephone interviews followed by refinement

- Domains: Current treatment routines, insulin dosing behaviors, barriers to optimal dosing, potential solutions for dosing optimization

Data Collection:

- Modality: Cross-sectional, noninterventional, web-based survey

- Recall Period: 30 days for dosing behaviors

- Primary Metrics: Proportion reporting missed/mistimed/miscalculated doses; mean number of dosing errors; reasons for suboptimal dosing; suggested solutions

- Ethical Considerations: Secure approval from institutional review board; obtain electronic informed consent from all participants

Statistical Analysis Plan

- Descriptive Statistics: Calculate proportions, means, and standard deviations for dosing irregularities

- Stratified Analyses: Compare patterns between T1D and T2D populations; examine HCP versus patient perspectives

- Qualitative Analysis: Thematically analyze open-ended responses regarding barriers and solutions

Conceptual Framework: From Clinical Burden to Algorithmic Solutions

The relationship between the global diabetes burden and the imperative for advanced glucose control technologies can be visualized through the following conceptual workflow:

Figure 1: Conceptual workflow linking diabetes epidemiology to technological solutions. This diagram illustrates the pathway from the growing global diabetes burden to the clinical imperative for advanced glucose control technologies like MPC algorithms.

For investigators working at the intersection of diabetes epidemiology and glucose control algorithm development, the following resources represent essential components of the research toolkit:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Diabetes Investigation

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Data Resources | IDF Diabetes Atlas [29], T1D Index [30], NCD-RisC datasets [31] | Epidemiological analysis, burden quantification, trend projection |

| Assessment Tools | Insulin Dosing Questionnaires [32], HbA1c measurements, Continuous Glucose Monitoring [33] | Behavioral assessment, glycemic control evaluation, adherence measurement |

| Algorithm Development Platforms | MATLAB/Simulink [34], Model Predictive Control frameworks, Prescribed finite-time control systems [34] | Control algorithm design, simulation, validation |

| Clinical Validation Systems | Artificial Pancreas systems [34], Continuous Glucose Monitors [33], Connected insulin pens [32] | Algorithm testing, clinical trial implementation, performance verification |

These resources enable a comprehensive research approach that spans from understanding population-level disease patterns to implementing and testing precise interventional technologies. The integration of epidemiological data with engineering solutions represents the cutting edge of diabetes management research.

The compelling statistics on global diabetes prevalence and the documented challenges in achieving optimal glycemic control create an undeniable clinical imperative for advanced management solutions. For researchers developing MPC algorithms, these epidemiological realities provide both justification for their work and specific clinical problems requiring resolution. The integration of robust global burden data with precise understanding of insulin dosing failures enables the creation of targeted technological interventions that address the most pressing challenges in diabetes care today. Future research directions should focus on validating MPC systems in real-world settings, particularly in populations experiencing the greatest disparities in care and outcomes.

Algorithm Design Strategies and Implementation Frameworks

Model Predictive Control (MPC) has emerged as a dominant control strategy for Artificial Pancreas (AP) systems to automate insulin delivery for people with Type 1 Diabetes (T1D). Zone-MPC represents a significant advancement over setpoint-based MPC by regulating blood glucose to a safe target zone rather than a single value, acknowledging that all glucose levels within a clinically defined interval are equally acceptable [35]. This approach inherently provides robustness to plant-model mismatch, model bias, and Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) sensor errors because the controller intervenes only when glucose predictions indicate excursions outside the safe zone, reducing unnecessary control actions and hypoglycemia risk [35] [36].

The incorporation of asymmetric input costs represents a fundamental innovation in zone-MPC formulation, directly addressing the critical clinical challenge of the inherent asymmetry in diabetes management [35] [37]. This control strategy recognizes that the consequences of hypoglycemia are immediate and potentially severe (including seizures, coma, and death), while the effects of temporary hyperglycemia, though undesirable, are less acutely dangerous [36]. The asymmetric penalty structure enables independent tuning of the controller's response to hyperglycemia (through insulin delivery above basal rate) and hypoglycemia (through insulin reduction or suspension), facilitating a safety-first approach essential for outpatient AP deployment [35] [37].

Mathematical Formulation of Zone-MPC with Asymmetric Penalties

Core Optimization Problem

The zone-MPC algorithm computes the optimal insulin correction dose ( u_k ) at each discrete time step by solving a constrained optimization problem. The cost function penalizes both predicted glucose excursions from the target zone and control efforts, with the distinctive feature of asymmetric penalties on insulin delivery [35] [37] [38].

The standard formulation is:

[ J(xi, u{0:Nu-1}) := \sum{k=1}^{Np} zk^2 + \sum{k=0}^{Nu-1} (\hat{R}\hat{u}k^2 + \check{R}\check{u}k^2) ]

Subject to: System dynamics and safety constraints.

Where:

- ( Np ) and ( Nu ) represent the prediction and control horizons, respectively

- ( z_k ) represents the distance of the predicted glucose from the target zone

- ( \hat{u}k := \max(uk, 0) ) (insulin delivery above basal rate)

- ( \check{u}k := \min(uk, 0) ) (insulin reduction below basal rate)

- ( \hat{R} ) and ( \check{R} ) are the asymmetric penalty weights on positive and negative insulin deviations, respectively [37]

Asymmetric Input Cost Structure

The separation of insulin input costs into positive (( \hat{R} )) and negative (( \check{R} )) components enables independent controller tuning for hyperglycemia correction versus hypoglycemia prevention [37].

Table 1: Interpretation of Asymmetric Penalty Parameters in Zone-MPC

| Parameter | Mathematical Expression | Physiological Effect | Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Input Penalty (( \hat{R} )) | Penalizes ( \hat{u}k = \max(uk, 0) ) | Modulates insulin delivery above basal rate | Higher values make the controller less aggressive in correcting hyperglycemia |

| Negative Input Penalty (( \check{R} )) | Penalizes ( \check{u}k = \min(uk, 0) ) | Modulates insulin reduction below basal rate | Higher values make the controller less likely to suspend insulin delivery when glucose is falling |

This formulation allows the control system to perform predictive pump suspension when hypoglycemia is imminent (by favoring negative ( u_k ) values when glucose is predicted to fall below the target zone) and subsequent predictive pump resumption once the hypoglycemia risk subsides [35].

Figure 1: Zone-MPC with asymmetric penalties logical workflow. The controller executes every 5 minutes, using state estimation and glucose prediction to solve an optimization problem that incorporates asymmetric penalties on insulin delivery above and below basal rate.

Quantitative Parameter Configurations and Performance Metrics

Controller Tuning Strategies

The asymmetric penalty parameters (( \hat{R} ), ( \check{R} )) can be configured to achieve different controller aggressiveness profiles, allowing customization based on patient needs and safety requirements [37].

Table 2: Zone-MPC Tuning Configurations with Asymmetric Penalties

| Controller Profile | ( \hat{R} ) Value | ( \check{R} ) Value | Hyperglycemia Response | Hypoglycemia Response | Clinical Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggressive | 800 | 500 | Fast correction | Slow to suspend insulin | Conservative hypoglycemia prevention strategy |

| Moderate (Default) | 7,000 | 100 | Balanced correction | Moderately responsive suspension | General outpatient use |

| Conservative | 50,000 | 10 | Slow correction | Fast pump suspension | High hypoglycemia risk patients |

Advanced Adaptive Tuning Strategies

Recent research has introduced glucose- and velocity-dependent control penalties that dynamically adjust ( \hat{R} ) and ( \check{R} ) based on predicted glucose values (( yk )) and their rate of change (( \muk )) [38]. The modified cost function becomes:

[ J(\cdot) := \sum{k=1}^{Np} (\check{z}k^2 + Q(vk)\hat{z}k^2 + \hat{D}\hat{v}k^2) + \sum{k=0}^{Nu-1} (\hat{R}(\muk,yk)\hat{u}k^2 + \check{R}(\muk,yk)\check{u}k^2) ]

This adaptive approach enables more aggressive hyperglycemia correction when glucose levels are high and rising, while implementing more conservative responses when glucose is falling or near the hypoglycemia threshold [38]. Clinical evaluations demonstrate that this method significantly improves mean glucose (153.8 mg/dL vs. 159.0 mg/dL; p < 0.001) and time in target range [70, 180] mg/dL (70.5% vs. 66.3%; p < 0.001) without increasing hypoglycemia risk [38].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

In Silico Testing Protocol

The UVA/Padova T1D Simulator, accepted by the FDA as a substitute for animal trials, provides the standard platform for preclinical validation of zone-MPC algorithms [35] [37] [39].

Protocol 1: Comprehensive In Silico Validation

- Subject Cohort: Utilize all 100 adult in-silico subjects of the UVA/Padova simulator to capture inter-subject variability [38]

- Meal Scenarios:

- 3 meals per day with increasing carbohydrate loads (50g, 75g, 100g)

- Test both announced and unannounced meal conditions

- Include meal-bolus mismatches (±30%, ±50%) to simulate real-world estimation errors [38]

- Controller Configurations: Compare asymmetric zone-MPC against:

- Performance Metrics:

Clinical Trial Protocol

Following successful in-silico testing, the zone-MPC with asymmetric penalties has been validated in FDA-approved clinical trials [35] [36].

Protocol 2: Clinical Validation Study

- Subject Recruitment: 32 adults with T1D, each completing two 25-hour closed-loop sessions [35]

- System Configuration:

- Portable Artificial Pancreas System (pAPS) running zone-MPC algorithm

- Diurnal target zone: [80, 140] mg/dL (day), [110, 170] mg/dL (night)

- Diurnal input constraint: Nighttime insulin limited to 1.8× basal rate [35]

- Meal Management:

- Mixed meal conditions (announced and unannounced)

- Option for meal-bolusing based on standard insulin-to-carbohydrate ratio [35]

- Safety Monitoring:

- Continuous clinical supervision

- Protocol for hypoglycemia rescue (carbohydrate administration or intravenous glucose)

- Pump suspension and resumption logging [35]

Figure 2: Experimental validation pathway for Zone-MPC with asymmetric penalties, showing the progression from in-silico testing to clinical trials.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Zone-MPC Development

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Platform | Function in Research | Key Features/Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Simulator | UVA/Padova T1D Simulator | Preclinical algorithm validation | 100-adult cohort; FDA-accepted; meal and exercise scenarios [37] [39] |

| Control Algorithm | Zone-MPC with asymmetric costs | Core control logic | ( \hat{R} ), ( \check{R} ) parameters; diurnal zones; velocity-weighting [35] [38] |

| State Estimation | Luenberger Observer | State variable estimation | Recursive formulation; tuning parameters Q, R [35] |

| CGM Model | Integrated CGM Simulator | Glucose measurement simulation | MARD <10%; realistic sensor noise [37] |

| Performance Analysis | Custom MATLAB Scripts | Statistical analysis and visualization | Time-in-range; hypoglycemia events; control variability [37] |

Performance Outcomes and Clinical Implications

The zone-MPC formulation with asymmetric penalties demonstrates significant clinical advantages in both in-silico and clinical settings. The adaptive version shows statistically significant improvements in mean glucose (153.8 mg/dL vs. 159.0 mg/dL; p < 0.001) and time in range [70, 180] mg/dL (70.5% vs. 66.3%; p < 0.001) compared to standard zone-MPC, without increasing hypoglycemia risk [38].

The algorithm's capability for predictive pump suspension before impending hypoglycemia and subsequent predictive resumption addresses a critical safety requirement for outpatient AP systems, particularly during nighttime when patients cannot respond to alarms [35]. Furthermore, the independent tuning of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia responses enables personalized therapy adaptations for specific patient populations, as demonstrated in pregnancy-specific zone-MPC implementations with tighter target zones (80-110 mg/dL daytime; 80-100 mg/dL overnight) [40].

The robustness of the control strategy has been verified under challenging conditions including meal-bolus mismatches, basal-rate inaccuracies, and unannounced exercise, maintaining safety across a broad spectrum of real-world scenarios [38]. This performance profile makes zone-MPC with asymmetric penalties a promising foundation for fully automated insulin delivery systems that minimize user burden while maximizing safety.

Model Predictive Control (MPC) has emerged as a leading control strategy for artificial pancreas (AP) systems in the management of Type 1 Diabetes (T1D). A fundamental challenge in MPC performance is the inherent plant-model mismatch caused by complex, time-varying patient physiology. Adaptive MPC strategies that dynamically adjust controller parameters based on real-time model accuracy offer a promising solution to this problem. This Application Note details a specific adaptive methodology that uses prediction residual analysis and a computed Trust Index to automatically modulate controller aggressiveness, enhancing both safety and effectiveness in blood glucose regulation. This approach is situated within a broader thesis that posits adaptive control is essential for achieving robust, personalized glucose control in free-living conditions.

Core Methodology

The adaptive algorithm quantifies the accuracy of the glucose prediction model by analyzing the history of prediction residuals and translates this accuracy into a dynamic tuning parameter for the MPC's cost function.

Prediction Residual Analysis

The first step involves the systematic collection and weighting of prediction residuals. For a current time ( t ), the residual for a prediction made ( k ) steps earlier is defined as: [ resk^t = y{t|t-k} - Gt ] where ( y{t|t-k} ) is the glucose prediction made at time ( t-k ) for the current time ( t ), and ( G_t ) is the current measured glucose value [37].

A pool of the most recent ( Nf ) residuals (e.g., ( Nf = 60 )) is maintained for each prediction step ( k ) across the prediction horizon ( Np ). To prioritize recent data, these residuals are penalized using a logarithmic forgetting function: [ \widetilde{res}{k,i}^{\,t} = resk^{\,t-i} \cdot \frac{\log(Nf - i + 1)}{\log Nf} ] where ( i ) indexes the historical data, making older residuals progressively less significant [37]. This creates a time-varying matrix of penalized residuals, ( \widetilde{res}{k,i}^{\,t} ), which serves as an empirical sample of the error distribution for the prediction model.

Trust Index and Confidence Interval Estimation

The Trust Index is derived empirically from the distribution of the penalized residuals. For each prediction step ( k ), the 5th and 95th percentiles of the penalized residual sample are calculated to establish a confidence interval for the prediction error: [ \breve{B}k = \min(\text{percentile}{5}(\widetilde{res}{k}^{\,t}), 0) \quad \text{and} \quad \widehat{B}k = \max(\text{percentile}{95}(\widetilde{res}{k}^{\,t}), 0) ] Here, ( \breve{B}k ) and ( \widehat{B}k ) represent the lower and upper bounds of the confidence interval, respectively [37]. A narrow confidence interval indicates high confidence in the model's predictions, whereas a wide interval indicates low confidence.

Dynamic MPC Tuning

In a Zone-MPC framework, the cost function typically penalizes glucose deviations from a target zone and insulin delivery deviations from a basal rate. The adaptive strategy dynamically adjusts the insulin penalties, ( \hat{R} ) (penalizing insulin delivery above basal) and ( \breve{R} ) (penalizing insulin suspension below basal), based on the Trust Index [37] [41].

- High Trust (Accurate Predictions): The controller is allowed to be more aggressive. The penalties ( \hat{R} ) and ( \breve{R} ) are decreased, enabling the controller to respond more vigorously to correct hyperglycemia and be less quick to suspend insulin, thereby improving overall glycemic control.

- Low Trust (Inaccurate Predictions): The controller becomes more conservative. The penalties ( \hat{R} ) and ( \breve{R} ) are increased. This results in less insulin delivery to counter hyperglycemia and a faster suspension of insulin to prevent hypoglycemia, prioritizing patient safety.

This dynamic adjustment creates a feedback loop where the controller's aggressiveness is continuously optimized based on its recent performance [37].

Experimental Protocol and Validation

In-Silico Validation Setup

- Simulator: The University of Virginia/Padova T1D Metabolic Simulator, accepted by the FDA for pre-clinical trials, is the standard for in-silico validation. It incorporates 10 virtual subjects representing inter-patient variability [37] [9].

- Simulation Scenario: Simulations typically cover 24 hours or more, involving multiple meals of varying carbohydrate loads (e.g., 50 g, 75 g, 100 g). A 2-hour open-loop warm-up period precedes closed-loop operation [37].

- Meal Compensation Strategies: