Managing Physiological Delays in Subcutaneous Insulin Absorption: Mechanisms, Models, and Advanced Solutions

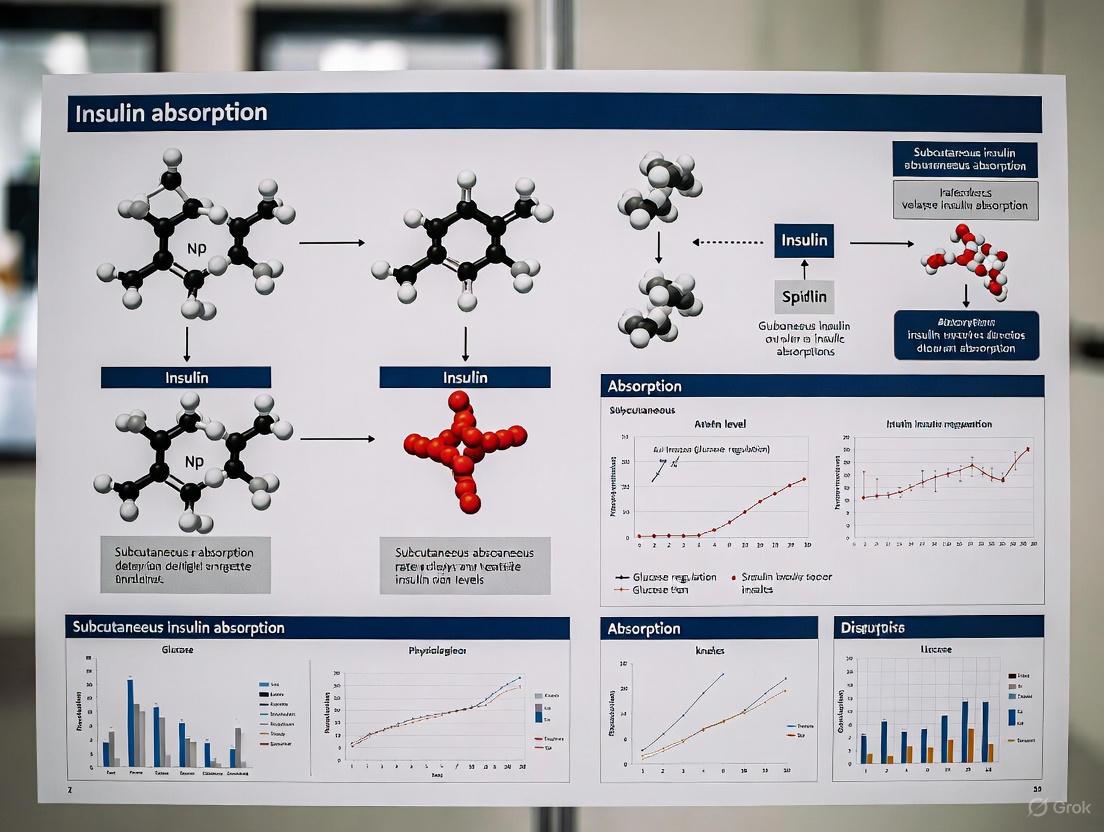

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the physiological factors contributing to delayed and variable subcutaneous insulin absorption, a major challenge in diabetes management.

Managing Physiological Delays in Subcutaneous Insulin Absorption: Mechanisms, Models, and Advanced Solutions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the physiological factors contributing to delayed and variable subcutaneous insulin absorption, a major challenge in diabetes management. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes current scientific understanding from foundational mechanisms to advanced intervention strategies. The scope spans the structural and molecular basis of absorption variability, innovative methodologies for studying depot kinetics, approaches for optimizing delivery systems, and comparative analyses of therapeutic modalities. The review aims to inform the development of next-generation insulin therapies and delivery technologies to achieve more predictable pharmacokinetics and improved glycemic control.

Deconstructing the Subcutaneous Barrier: The Structural and Molecular Basis of Absorption Delays

Core Concepts FAQ

1. What are the key anatomical components of the subcutaneous injection site? The subcutaneous tissue, located between the dermis and muscle, is a complex, multi-layered domain. Its structure consists of superficial adipose tissue, a fibrous connective tissue layer (membranous layer), and deep adipose tissue bounded by fascia and muscle walls. The tissue is composed of adipocytes (fat cells) bound by an extracellular matrix (ECM) and is interspersed with blood vessels and lymphatic channels [1]. The thickness of this layer varies by individual body mass index (BMI), age, gender, and injection location (e.g., abdomen, arm, leg) [1].

2. How does the Extracellular Matrix (ECM) composition influence drug absorption? The ECM is a dynamic structure that presents a primary physiological barrier to the absorption of subcutaneously administered drugs like insulin [2]. It is composed of a network of fibrous proteins and proteoglycans that determine tissue integrity and resistance to fluid flow [1].

- Fibrous Proteins: These provide structural integrity.

- Proteoglycans and Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs): These highly negatively charged molecules form a gel-like, hydrous phase that controls interstitial fluid content [2] [1].

- Hyaluronic Acid: A high-molecular-weight GAG with significant fluid exclusion volume, contributing to tissue viscoelasticity. Its enzymatic degradation is a method to enhance drug absorption [1].

- Chondroitin Sulfate: A highly anionic GAG that can interact with cytokines and other matrix components [1].

3. What is the role of adipose tissue in subcutaneous drug delivery? Adipose tissue, organized into lobules, is the primary cell type in the subcutis. Adipocytes store triglycerides and are separated by connective tissue septae that contain most of the area's blood and lymph vessels [2] [3]. Upon injection, the formulated drug can cause hydraulic fracturing of the adipose tissue, creating micro-cracks that influence the dispersion and formation of the drug depot [1].

4. How do vascular and lymphatic systems contribute to drug uptake from the subcutis? The subcutaneous space contains an inter-related network of blood capillaries and lymphatic vessels, which are the two primary pathways for drug absorption into the systemic circulation [1].

- Blood Capillaries: These are the main route for absorbing smaller molecules like insulin monomers and dimers [2].

- Lymphatic Capillaries: These are critical for the uptake of larger molecules, such as therapeutic antibodies, due to their structure which lacks tight junctions, allowing larger molecules to enter [2] [1]. Lymphatic vessel density is highest in the dermis and fascia but low in adipose layers [1].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

1. Issue: High inter- and intra-subject variability in insulin absorption kinetics.

- Potential Cause: Variability in subcutaneous tissue structure, including differences in adipose tissue thickness and ECM composition between subjects and injection sites (e.g., abdomen vs. arm) [2] [1].

- Solution:

- Standardize injection sites and techniques across study participants [4].

- Use shorter needles (e.g., 4-5 mm) to ensure consistent subcutaneous delivery and avoid unintentional intramuscular injection, which has a different and more variable absorption profile [4].

- Account for patient factors like BMI in your experimental design, as subcutaneous thickness is directly related to it [1].

2. Issue: Slower-than-expected absorption rate for rapid-acting insulin analogs.

- Potential Cause: The rate-limiting step is often the dissociation of insulin hexamers into absorbable monomers and dimers in the subcutaneous depot, not just blood flow [5] [6].

- Solution:

- Consider formulations that include excipients like niacinamide (as in Fiasp) to promote local vasodilation and faster disassociation [4].

- Investigate the use of recombinant human hyaluronidase, an enzyme that temporarily degrades hyaluronic acid in the ECM, to reduce diffusion barriers and accelerate dispersion and absorption [1].

3. Issue: Unpredictable glucose response during metabolic studies involving exercise.

- Potential Cause: Exercise and local temperature increases can significantly accelerate insulin absorption by increasing local blood flow, leading to exercise-induced hyperinsulinemia and hypoglycemia [4] [7].

- Solution:

- In exercise studies, carefully control for and monitor ambient and skin temperature at the injection site [4].

- Instruct study participants to avoid injecting insulin into limbs that will be heavily exercised [4].

- Consider experimental local warming devices to study the maximal effect of this variable, as it can reduce time to peak insulin action by approximately 35 minutes [7].

4. Issue: Tissue induration, lipohypertrophy, or poor absorption at repeated injection sites.

- Potential Cause: Repeated injections in the same area can cause localized tissue remodeling, scarring, and buildup of fat, which alters the normal architecture and absorption kinetics [1].

- Solution:

The following tables summarize key quantitative relationships and experimental data from the literature.

Table 1: Impact of Physiological Factors on Insulin Absorption Kinetics

| Factor | Observed Effect on Absorption | Magnitude of Effect / Correlation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adipose Tissue Thickness | Slower absorption with increased thickness | Negative correlation; Time to peak insulin concentration delayed by ~31 min in high BMI group [4]. | [4] |

| Local Skin Warming (to 40°C) | Faster time to peak action and concentration | Time to peak insulin action reduced from ~111 min to ~77 min [7]. | [7] |

| Injection Depth (IM vs SubQ) | Intramuscular injection is faster and more variable | Absorption rate increased by ~150% during exercise with IM injection [4]. | [4] |

| Sauna (Ambient Heat) | Increased disappearance rate from injection site | 110% greater disappearance of insulin from injection site [4]. | [4] |

Table 2: Key ECM Components and Their Properties

| ECM Component | Key Characteristics | Proposed Role in Drug Absorption |

|---|---|---|

| Collagen I, III, V | Fibrillar proteins; net cationic at physiological pH [1]. | Provides structural scaffold; may interact electrostatically with proteins [2] [1]. |

| Hyaluronic Acid | High MW (6-8 x 10^6); pKa ~2.9; high viscosity & fluid exclusion [1]. | Major determinant of interstitial resistance; target for hyaluronidase to enhance absorption [1]. |

| Chondroitin Sulfate | Highly anionic oligosaccharide (carboxylate & sulfate groups) [1]. | Contributes to gel-like phase; binds cytokines and matrix components [1]. |

| Elastin | Hydrophobic fibers formed from tropoelastin [1]. | Provides mechanical elasticity to the tissue [2]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Detailed Protocol: Evaluating the Impact of Local Warming on Insulin Pharmacokinetics

This methodology is adapted from studies using devices like the InsuPatch to investigate the effect of controlled local heat on insulin absorption [7].

1. Experimental Setup:

- Design: Randomized, crossover study where subjects act as their own controls.

- Subjects: Patients with type 1 diabetes on insulin pump therapy.

- Intervention: Activation of a local warming device (set to 40°C) for 15 minutes before and 60 minutes after a bolus insulin injection. The control session is identical without activation.

2. Procedures:

- Euglycemic Clamp: suspend basal insulin infusion and administer a standardized bolus of rapid-acting insulin (e.g., 0.2 U/kg of insulin aspart). Maintain blood glucose between 90-100 mg/dL using a variable-rate dextrose infusion.

- Blood Sampling: Collect serum samples at frequent intervals (e.g., every 10 min for the first 90 min) to measure plasma insulin levels for pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis.

- Key Pharmacodynamic (PD) Parameters: Calculate from the Glucose Infusion Rate (GIR) profile:

- Time to maximum GIR (TGIRmax)

- Time to half-maximum GIR (T50%GIRmax)

- Area Under the Curve for GIR from 0-30 min (AUCGIR 0-30min)

3. Outcome Analysis:

- Primary PK Endpoints: Time to maximum increment in plasma insulin (TΔCmax), area under the insulin concentration curve from 0-30 min (AUCΔCins 0-30min).

- Expected Outcome: Local warming should significantly reduce TGIRmax and TΔCmax, and increase AUCGIR 0-30min and AUCΔCins 0-30min, demonstrating accelerated absorption and action [7].

Workflow Diagram: From Injection to Systemic Absorption

Workflow Diagram: Local Warming Experiment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Subcutaneous Absorption Research

| Item | Function / Application in Research | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid-Acting Insulin Analogs | Model protein for studying SC absorption kinetics; modified for faster disassociation. | Insulin aspart (NovoRapid), lispro (Humalog), glulisine (Apidra) [2] [4]. |

| Local Warming Device | Experimentally manipulates local blood flow to study its impact on absorption kinetics. | InsuPatch device; can be set to specific temperatures (e.g., 38.5°C, 40°C) [7]. |

| Recombinant Human Hyaluronidase | Enzyme that degrades hyaluronic acid in the ECM; used to reduce diffusion barriers and act as a "permeation enhancer." [1] | PH20 enzyme; investigational use to accelerate drug dispersion and absorption [1]. |

| Euglycemic Clamp System | Gold-standard method for assessing insulin pharmacodynamics (action) and indirectly, pharmacokinetics. | Requires precise IV dextrose infusion and frequent blood glucose monitoring (e.g., YSI analyzer) [7]. |

| Laser Doppler Imager | Non-invasively measures and monitors local cutaneous blood flow (perfusion) at the injection site. | Moor Laser Doppler Imager; provides quantitative blood flow data in arbitrary perfusion units [6]. |

| Short Needles (4-6 mm) | Ensures consistent subcutaneous injection depth and avoids intramuscular deposition. | Standardized for research to minimize variability related to injection technique [4]. |

FAQs: Insulin Oligomerization and Experimental Handling

Q1: What are the key oligomeric states of insulin, and why are they important for drug formulation?

Insulin exists in a dynamic equilibrium between several oligomeric states: monomers, dimers, tetramers, and hexamers. The concentration of each oligomer is determined by equilibrium constants (KMD for monomer-dimer and KDH for dimer-hexamer) [2]. This self-assembly is crucial for drug development because the hexameric form is the primary storage state in pharmaceutical formulations due to its stability, but it must dissociate into bioavailable monomers to be absorbed into the bloodstream and become physiologically active [8] [2]. Understanding and controlling these pathways allows for the development of insulins with either rapid or protracted action profiles.

Q2: What experimental challenges are associated with characterizing insulin oligomers?

Traditional ensemble methodologies (e.g., sedimentation equilibrium, dynamic light scattering) face significant challenges:

- Indirect Measurement: They correlate changes in macroscopic properties with the average oligomerization state and rely on fitting data with simplified models, which may not account for all possible intermediates or pathways [8].

- Concentration Limitations: Their low sensitivity confines reliable readouts to the µM range, which is above the physiologically relevant pM-nM concentrations found in blood [8].

- Fragile Complexes: Weak, self-assembled oligomeric structures can dissociate or re-equilibrate during analysis, particularly in chromatographic methods where buffer conditions change [9].

Q3: How do excipients like zinc and phenol alter the oligomerization pathway?

Excipients reroute the self-assembly pathway to favor specific oligomers:

- Zinc Ions: Stabilize the hexameric assembly by coordinating to HisB10 on insulin dimers [8].

- Phenolic Ligands (e.g., phenol, meta-cresol): Further stabilize hexamers by inducing a conformational change from the T-state (tense) to the more stable R-state (relaxed) [8]. Upon subcutaneous injection, these excipients disperse into the tissue, shifting the equilibrium and allowing hexamers to dissociate into absorbable dimers and monomers [2].

Q4: What is the relationship between oligomeric state and subcutaneous absorption rate?

The absorption rate is directly dependent on the oligomer's size [2] [4]:

- Monomers and Dimers: Readily absorbed by blood capillaries.

- Hexamers: Too large for direct capillary absorption; they must first dissociate into smaller units. Some hexamers may be absorbed via the lymphatic system due to their larger size [2]. This necessary dissociation is a primary factor causing the delayed onset of action after a subcutaneous injection.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inconsistent Results in Oligomer Distribution Analysis

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Dissociation of weak oligomeric complexes during chromatographic separation [9].

- Solution: Employ non-invasive, in-situ techniques like polarized Excitation-Emission Matrix (pEEM) spectroscopy with Multivariate Curve Resolution (MCR). This method allows for the quantification of fragile oligomer populations in solution without disruption [9].

- Cause: Reliance on ensemble techniques that cannot detect all intermediate species or pathways, such as monomeric additions to larger oligomers [8].

- Solution: Utilize single-molecule techniques like Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy. This method directly observes and quantifies the kinetics of individual assembly and disassembly events, providing a more complete picture of the pathway organization [8].

Problem 2: High Intra-Assay Variability in Measuring Insulin Absorption Kinetics

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inadvertent intramuscular injection due to short needle lengths or low subcutaneous tissue thickness, which leads to faster and more variable absorption [4].

- Solution: Standardize injection protocols using shorter needles (e.g., 4-5 mm) confirmed by ultrasound to ensure consistent subcutaneous delivery [4].

- Cause: Variable local blood flow at the injection site, which can be influenced by ambient temperature or physical activity [4].

- Solution: Control for environmental factors such as temperature and advise research subjects to avoid strenuous exercise involving the injection site limb prior to and during kinetic studies.

Quantitative Data on Insulin Oligomerization

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Rate Constants and Oligomer Abundance

| Parameter | Value / Observation | Experimental Condition | Source / Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monomer-Dimer Constant (KMD) | 103 to 105 M-1 | Varies with conditions and model | Ensemble Recordings [8] |

| Dimer-Hexamer Constant (KDH) | 108 to 109 M-2 | Varies with conditions and model | Ensemble Recordings [8] |

| Key Assembly Pathways | Monomeric, Dimeric, and Tetrameric additions | Direct observation at ~10 nM | Single-Molecule TIRF [8] |

| Effect of Zn2+ & Phenol | Reroutes pathway, favors dimeric/tetrameric addition & enhances hexamer stability | Added to formulation | Single-Molecule TIRF & Model [8] |

| Oligomer Abundance | High oligomer abundance at nM concentrations; lower effective monomer concentration than previously thought | nM regime | Single-Molecule Recordings [8] |

Table 2: Impact of Formulation on Pharmacokinetics

| Insulin Type | Key Characteristics | Time to Peak Concentration (Tmax) |

|---|---|---|

| Regular Human (SC injection in rats) | Unmodified formulation | 22.7 (±14.2) minutes [10] |

| Regular Human (via Vascularizing Microchamber in rats) | Administered through an implanted device promoting local vascularization | 7.5 (±4.5) minutes [10] |

| Ultra-Rapid Analogues (e.g., Fiasp, Lyumjev) | Contains excipients to accelerate disassembly and absorption | ~57-63 minutes in humans [10] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Single-Molecule Analysis of Insulin Oligomerization via TIRF

Purpose: To directly observe and kinetically characterize all intermediate steps in insulin self-assembly and disassembly in equilibrium [8].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Chemically label human insulin with a fluorophore (e.g., ATTO655) at a site that does not interfere with self-assembly, such as LysB28.

- Confirm that labeling does not alter kinetics via control experiments with a 1:1 mixture of labeled and unmodified insulin.

- Immobilization and Imaging:

- Allow a low concentration (e.g., 10 nM) of fluorescently labeled insulin to equilibrate on a passivated microscopy surface.

- Acquire time-series images using TIRF microscopy, which immobilizes molecules for observation while excluding signal from solution.

- Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Use quantitative image analysis to determine coordinates and intensity of each particle.

- Record time-dependent intensity fluctuations, which appear as discrete steps corresponding to binding and unbinding events.

- Analyze trajectories using a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) with a seven-state model (background, monomer through hexamer) to classify oligomeric states and extract dwell times and transition kinetics.

Purpose: To reliably measure the size and distribution of fragile insulin oligomers in solution without causing dissociation [9].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare insulin solutions under conditions that promote specific oligomeric states (e.g., with/without Zn2+).

- pEEM Measurement: Collect full EEM spectra, including the Rayleigh scatter (RS) band, using polarized light to enhance the scatter signal.

- Data Analysis:

- Rayleigh Scatter Analysis: The volume under the RS band correlates linearly with the molecular weight of the protein/oligomer. Use this to validate size changes.

- Multivariate Curve Resolution (MCR): Apply MCR to the fluorescence signal in the EEM to resolve and quantify the proportion of individual oligomeric components in heterogeneous mixtures.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram: Insulin Oligomerization and Absorption Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents for Oligomerization and Absorption Studies

| Item | Function / Role in Research |

|---|---|

| Fluorophore-Labeled Insulin (e.g., HI655) | Enables direct visualization of oligomerization dynamics in single-molecule assays like TIRF microscopy [8]. |

| Zinc Chloride (ZnCl₂) | An excipient used to stabilize insulin hexamers; essential for studying protracted formulations [8] [2]. |

| Phenol / Meta-Cresol | Excipients that stabilize hexamers and act as preservatives; used to study the T-state to R-state transition [8] [2]. |

| Passivated Microscopy Surfaces | Provide a non-reactive surface for immobilizing insulin molecules during single-molecule fluorescence experiments [8]. |

| Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) Microchambers | Implantable devices with specific pore sizes used to study accelerated absorption kinetics in vivo by promoting local vascularization [10]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How does local skin temperature at the injection site influence insulin absorption variability? Increased local temperature elevates skin blood flow, which accelerates the disappearance of insulin from the subcutaneous (SC) depot. Application of local skin-warming to 40°C has been shown to significantly shorten the time to peak insulin action compared to control conditions (77 ± 5 minutes vs. 111 ± 7 minutes) [4]. Even ambient warming, such as sitting in a sauna, can cause a 110% greater disappearance of insulin from the injection site [4]. This effect can contribute to an unpredictable drop in blood glucose.

Q2: What is the impact of subcutaneous tissue (SC) thickness and morphology on insulin absorption? A thicker subcutaneous adipose tissue layer is associated with a slower and more tempered absorption profile [4]. The tissue's structure acts as a physical barrier; insulin must navigate through a network of adipocytes and an extracellular matrix composed of connective tissue, collagen, and glycosaminoglycans [2] [4]. Furthermore, upon injection, the formulation can form irregular "heaps" or depots, the size and shape of which vary between injections, contributing to pharmacokinetic variability [11].

Q3: Why does intramuscular injection pose a greater risk of variability, especially around exercise? Insulin absorption is significantly faster and more variable from intramuscular sites compared to subcutaneous tissue. This effect is amplified during exercise, with one study showing an exercise-induced increase in absorption rate for intramuscular injection but not for subcutaneous injection [4]. This leads to a greater and more unpredictable drop in blood glucose during exercise with intramuscular injections.

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Variability

Protocol 1: Quantifying the Effect of Local Temperature on Insulin Absorption Kinetics

- Objective: To determine the effect of controlled local skin warming on the pharmacokinetic (PK) profile of a subcutaneously administered insulin bolus.

- Methodology:

- Participant Preparation: Recruit subjects (e.g., individuals with type 1 diabetes or healthy volunteers) under fasting conditions.

- Baseline PK Profile: Administer a standardized dose of rapid-acting insulin (e.g., insulin aspart) into the subcutaneous tissue of the abdomen. Collect frequent blood samples to establish a baseline PK curve (e.g., serum insulin concentration over 4-6 hours).

- Intervention PK Profile: On a separate visit, apply a local skin-warming device (set to 40°C) to the abdominal injection site for a defined period pre- and post-injection. Administer the same standardized insulin dose and repeat the blood sampling protocol.

- Data Analysis: Calculate key PK parameters for both conditions: time to peak insulin concentration (T~max~), maximum insulin concentration (C~max~), and area under the curve (AUC). Compare parameters using paired statistical tests (e.g., paired t-test).

Protocol 2: Visualizing Subcutaneous Depot Formation and Permeation Using X-Ray Imaging

- Objective: To characterize the formation and spread of an injected solution in subcutaneous and muscle tissues ex vivo.

- Methodology (Based on ex vivo porcine tissue model) [12]:

- Tissue Preparation: Obtain fresh porcine subcutaneous and muscle tissues. Secure the tissue samples in a custom holder.

- Injection and Imaging: Inject a radiopaque solution (e.g., iodine-based contrast) into the tissue using a syringe pump at controlled, slow injection rates (e.g., 25-100 μL/min) to simulate pump delivery. Use real-time X-ray imaging to capture the dynamic permeation of the solution.

- Data Extraction and Analysis:

- Wetting Front (WF) Tracking: Quantify the movement of the solution's wetting front in horizontal (WF~h~) and vertical (WF~v~) directions over time.

- Aspect Ratio Calculation: Calculate the aspect ratio (WF~v~/WF~h~) of the depot to analyze its shape and symmetry.

- Permeability Estimation: Use the measured flow rate (q) and wetting front radius (r~t~) to estimate the tissue's hydraulic permeability (k) using the derived formula:

k = [12.96 / π] * r_t * [q / (q + 31.08)][12].

Table 1: Effect of Injection Rate on Depot Formation in Subcutaneous Tissue (Ex Vivo Porcine Model) [12]

| Injection Rate (μL/min) | Region | Aspect Ratio (WF~v~/WF~h~) | Permeability, k (m⁴/N·s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | Injection Region (IR) | 0.89 ± 0.10 | 1.07-1.38 × 10⁻¹³ |

| 100 | Injection Region (IR) | 0.94 ± 0.05 | 1.07-4.41 × 10⁻¹³ |

| 25 | Diffusion Region (DR) | 0.73 ± 0.02 | - |

| 100 | Diffusion Region (DR) | 0.85 ± 0.01 | - |

Table 2: Impact of Physiological Factors on Insulin Absorption [2] [4]

| Factor | Effect on Absorption | Clinical/Research Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Local Temperature Increase | Significantly faster absorption and shorter time to peak action. | A source of intra-individual variability; requires caution during activities that heat the injection site. |

| Intramuscular Injection | Faster and more variable absorption compared to subcutaneous injection; effect is dramatically amplified by exercise. | Use of shorter needles (4-5 mm) is recommended to minimize unintentional intramuscular delivery. |

| Increased SC Tissue Thickness | Slower absorption rate and longer time to peak plasma concentration. | Contributes to inter-individual variability in insulin response. |

Signaling Pathways and Physiological Relationships

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Investigating SC Insulin Absorption

| Item | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Radiopaque Contrast Agents | Used in conjunction with real-time X-ray imaging to visually track the permeation and depot formation of an injected solution in ex vivo tissue models [12]. |

| 125I-Labeled Insulin | Allows for quantitative tracking of insulin disappearance from the injection site and appearance in plasma in human and animal studies [4]. |

| Recombinant Human Insulin & Analogues | The standard active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) for studying the differential absorption kinetics of rapid-acting, short-acting, and long-acting formulations [2] [4]. |

| Local Skin-Warming Devices | Precision tools (e.g., controlled-temperature pads) to apply consistent thermal intervention for studying the effect of temperature on absorption kinetics [4]. |

| Ex Vivo Porcine Tissue | A well-accepted model system due to its morphological and mechanical similarity to human subcutaneous tissue, ideal for initial mechanistic studies [12]. |

| Hyaluronidase | An enzyme that cleaves hyaluronan in the extracellular matrix. Used in research to investigate how reducing SC tissue barrier resistance affects insulin absorption kinetics [4]. |

This Technical Support Center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers investigating physiological delays in subcutaneous insulin absorption. The content is designed to assist scientists in navigating common experimental challenges in this field.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How does obesity specifically alter subcutaneous (s.c.) insulin depot kinetics? Obesity is associated with significant alterations in s.c. insulin depot kinetics. In diet-induced obese rat models, high-fat diet (HFD) groups exhibited delayed insulin absorption from the s.c. tissue compared to low-fat diet (LFD) controls. This delay was correlated with the formation of smaller injection depots and a slower depot disappearance rate from the injection site. The rate of depot disappearance was inversely correlated with body fat mass [13] [14].

FAQ 2: What are the key molecular mechanisms linking adipose tissue function to systemic insulin sensitivity? Adipocytes are master regulators of systemic glucose and insulin homeostasis, far beyond being simple storage depots. Key mechanisms include:

- GLUT4 Translocation: Insulin stimulates glucose uptake in adipocytes by triggering the translocation of GLUT4 glucose transporters to the plasma membrane [15].

- Signaling Pathways: The PI3K/AKT pathway is a central signaling cascade in insulin action. Disruptions in this pathway, often driven by a pro-inflammatory state with elevated cytokines like TNF-α, contribute to insulin resistance [16].

- Transcriptional Regulation: Transcription factors like Carbohydrate Response Element Binding Protein (ChREBP) are activated by glucose and regulate de novo lipogenesis (DNL) in fat. Adipose ChREBP expression is tightly linked to whole-body insulin sensitivity [15].

FAQ 3: What is the best method to quantify adiposity in my animal model to study its impact on insulin kinetics? While body weight and fat mass are standard, more precise methods are recommended. In rodent studies, body composition analyzers like EchoMRI can precisely differentiate lean and fat mass [13]. For a more refined assessment that better reflects abdominal adiposity, Relative Fat Mass (RFM) is a superior alternative to Body Mass Index (BMI). RFM is calculated using a sex-specific formula based on waist circumference and height and better correlates with actual fat mass and cardiometabolic risk [17].

Troubleshooting Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: High Variability in Insulin Pharmacokinetic (PK) Data

Problem: Significant inter-individual variation in insulin absorption rates obscures experimental results.

Solution: Implement rigorous standardization and consider the role of adiposity.

- Standardize Injection Technique: Ensure consistent injection volume, depth, and site across all subjects. In rodent studies, neck and flank dosing can yield different absorption rates [13].

- Characterize Body Composition: Do not rely on body weight alone. Measure fat mass using a dedicated body composition analyzer (e.g., EchoMRI) at the start and throughout the study to stratify subjects based on adiposity [13].

- Increase Repeated Measurements: To account for inherent variability, perform repeated pharmacokinetic experiments on the same subject across different days and include these replicates in a mixed-model statistical analysis [13].

Challenge 2: Visualizing and Quantifying the Subcutaneous Injection Depot

Problem: Difficulty in directly observing the formation and dissipation of the s.c. insulin depot.

Solution: Utilize advanced imaging techniques to visualize depot kinetics.

- Methodology (μCT Imaging):

- Prepare Formulation: Mix insulin aspart with a contrast agent like iomeprol (e.g., 80/20 ratio) [13].

- Administer Dose: Perform a s.c. injection in the anesthetized animal using a standardized volume and technique.

- Image Time-Course: Subject the animal to micro X-ray computed tomography (μCT) scans at multiple time points post-dosing (e.g., 1, 3, 7, 13, 17 minutes) to capture depot dynamics [13].

- Quantify Depot Metrics: Use imaging software (e.g., Imaris) to calculate depot volume and surface area over time. These parameters are closely correlated and serve as key metrics for depot kinetics [13].

Challenge 3: Disentangling Absorption from Clearance

Problem: An observed reduction in plasma insulin exposure could be due to either delayed s.c. absorption or enhanced systemic clearance.

Solution: Conduct a separate intravenous (i.v.) bolus study to directly assess insulin clearance.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Administer insulin aspart (e.g., 1 nmol kg⁻¹) via i.v. injection to subjects from both control and high-adiposity groups [13].

- Collect blood samples at frequent intervals post-dosing (e.g., 3, 7, 15, 30, 60, 120, 180 minutes).

- Analyze plasma insulin levels and calculate pharmacokinetic parameters. If no significant difference in clearance is found between groups, then differences observed after s.c. dosing can be confidently attributed to alterations in absorption at the injection site [13].

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from a seminal study on diet-induced obesity and insulin absorption in a rat model [13].

| Parameter | High-Fat Diet (HFD) Group | Low-Fat Diet (LFD) Group | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body Weight (30 weeks) | 777 ± 13 g | 658 ± 20 g | < 0.05 |

| Fat Mass | Significantly increased | Baseline | < 0.001 |

| Insulin Concentration (5 min post-s.c. dose) | Significantly lower | Higher | < 0.001 |

| AUC0–60 min | Reduced | Higher | < 0.01 |

| Injection Depot Volume | Smaller | Larger | < 0.05 |

| Depot Disappearance Rate | Slower | Faster | < 0.05 |

| Correlation: Fat Mass vs. Depot Disappearance | Inverse correlation | - | < 0.05 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Insulin Aspart | A rapid-acting insulin analog used to study the pharmacokinetics of subcutaneously administered insulin [13]. |

| Iomeprol | A contrast agent mixed with insulin for non-invasive visualization of the injection depot using μCT imaging [13]. |

| Luminescent Oxygen Channeling Immunoassay (LOCI) | A technology used for the precise quantification of plasma insulin aspart concentrations in pharmacokinetic studies [13]. |

| ChREBP siRNA/Knockout Models | Tools to investigate the role of the lipogenic transcription factor ChREBP in linking adipocyte glucose metabolism to systemic insulin sensitivity [15]. |

| EchoMRI Body Composition Analyzer | Provides precise, non-invasive measurement of lean and fat mass in live animal models, crucial for stratifying subjects by adiposity [13]. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Insulin Signaling Pathway in Adipocytes

Diagram Title: Insulin Signaling and Resistance Mechanisms

Experimental Workflow for Depot Kinetics

Diagram Title: Studying Depot Kinetics and PK

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Researchers

FAQ 1: What are the primary cellular drivers of the foreign body response against subcutaneous catheters? The inflammatory response to an implanted catheter is initiated by the adsorption of host proteins to the catheter surface, forming a conditioning film. This triggers the activation of the innate immune system. Macrophages are the key cellular players; they attempt to phagocytose the material and, upon failing, can fuse to form foreign body giant cells. This process is sustained by a continuous recruitment of monocytes from the bloodstream. The persistent release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α) and fibrogenic factors (e.g., TGF-β) by these activated cells drives the subsequent formation of an avascular, collagen-rich fibrous capsule around the catheter, which constitutes the mechanical barrier [18] [19].

FAQ 2: How does the resulting fibrous capsule potentially impact chronic subcutaneous drug dosing? The formation of a dense, fibrous capsule around a catheter can significantly alter the pharmacokinetics of subcutaneously administered drugs. This mechanical barrier acts as a diffusion block, reducing and delaying the transport of drug molecules from the catheter site into the systemic circulation. Furthermore, the altered and often reduced vascularization within the capsule can limit the efficient absorption of drugs into the bloodstream. For drugs like insulin, whose absorption kinetics are critical for glycemic control, this can lead to increased within-subject variability and unpredictable pharmacological effects, complicating research outcomes and therapeutic efficacy [2] [4].

FAQ 3: What material properties of a catheter are known to influence the severity of the inflammatory response? Research indicates that the following material properties are critical in modulating the host inflammatory response:

- Surface Topography: Nano- and micro-scale surface textures can influence protein adsorption and direct immune cell behavior.

- Surface Chemistry: Hydrophilic coatings and zwitterionic polymers can create bio-inert surfaces that resist protein fouling.

- Biocompatibility: Materials like medical-grade silicone are generally preferred over latex due to their inherent stability and lower tendency to provoke a severe response. The ongoing development of antimicrobial impregnations and bio-inspired coatings aims to directly counter biofilm formation and the ensuing inflammation [19].

Key Experimental Data and Methodologies

Quantitative Insights into Catheter-Associated Inflammation and Insulin Absorption

Table 1: Factors Influencing Subcutaneous Insulin Absorption & Variability

| Factor Category | Specific Factor | Impact on Absorption & Variability |

|---|---|---|

| Drug Formulation | Insulin Oligomer State (Monomer vs. Hexamer) | Monomers (6 kDa) absorb rapidly; hexamers (36 kDa) must dissociate first, slowing absorption [2]. |

| Injection/Infusion Site | Subcutaneous Tissue Thickness | An inverse relationship exists; thicker adipose tissue layers are associated with tempered and more variable absorption profiles [4]. |

| Injection Depth (Subcutaneous vs. Intramuscular) | Intramuscular injection leads to more rapid and variable absorption, especially during exercise [4]. | |

| Physiological Conditions | Local Temperature | Skin warming (e.g., to 40°C) significantly accelerates insulin absorption and time to peak action [4]. |

| Physical Exercise | Increases blood flow, which can accelerate absorption from depots, particularly in active muscle beds [4]. |

Table 2: Catheter-Related Inflammatory & Infection Metrics

| Parameter | Value or Incidence | Context / Note |

|---|---|---|

| CAUTI Incidence | 20-40% of nosocomial infections [19] | Leading type of hospital-acquired infection. |

| Bacteriuria Incidence | 3-8% per catheter day [19] [20] | Nearly universal in long-term catheterized patients. |

| Mortality Rate (CAUTI) | ~10% [19] | Highlights significant clinical impact. |

| Primary CAUTI Pathogens | E. coli (28%), Candida spp. (18%), Enterococcus spp. (17%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (14%) [19] | Isolated from infections in Europe. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Modeling Catheter Colonization

A 2025 study published in Nature Communications provides a quantitative mathematical model for bacterial colonization of urinary catheters, offering a framework that can be adapted for research on inflammatory barriers [20].

Objective: To create a predictive model for bacterial colonization dynamics on indwelling catheters, distinguishing factors affecting short-term vs. long-term outcomes.

Methodology Workflow:

System Compartmentalization: The catheter environment is divided into four interconnected compartments:

- Outside Catheter Surface: Modeled using the Fisher-Kolmogorov-Petrovsky-Piskunov (FKPP) equation to simulate bacterial proliferation and spread as a population wave.

- Bladder: Treated as a well-mixed reservoir with bacterial logistic growth and constant dilution from urine flow.

- Luminal Flow: The urine flow through the catheter lumen is modeled with an advection-diffusion equation, assuming a Poiseuille flow profile.

- Luminal Surface: Also uses an FKPP equation, with an added source term for bacterial deposition from the luminal flow.

Parameterization: Key parameters are defined for simulation, including:

- Patient-specific: Urethral length, urine production rate, residual bladder volume.

- Catheter-specific: Material surface properties, length.

- Pathogen-specific: Bacterial growth rate, motility.

Computer Simulation & Analysis: Simulations are run for short-term (days) and long-term (months) durations. The model predicts key outcomes such as the time to bacteriuria and the steady-state bacterial abundance, allowing researchers to identify which factors are most critical in each scenario [20].

Key Findings:

- Long-term outcomes (e.g., established bacteriuria) are primarily controlled by the rate of urine production and residual urine volume in the bladder.

- Short-term outcomes (e.g., time to initial colonization) are controlled by catheter surface properties, urethral length, and bacterial motility.

- This model suggests that interventions like antimicrobial coatings are likely more effective for short-term catheterization, while increasing fluid intake may be a more effective strategy for long-term patients [20].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Inflammatory Cascade in Foreign Body Response

Diagram Title: Inflammatory Cascade Leading to a Mechanical Barrier

Integrated Research Workflow for Subcutaneous Dosing Studies

Diagram Title: Research Workflow for Dosing Studies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Investigating Catheter-Induced Barriers

| Item / Reagent | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Medical-Grade Silicone Catheters | The standard substrate for implantation studies; can be modified with various coatings. |

| Zwitterionic Polymer Coatings | Used to create ultra-low-fouling surfaces to test the hypothesis that reducing protein adsorption mitigates the foreign body response [19]. |

| Recombinant Insulin & Analogues | Model drugs (e.g., insulin lispro, aspart) with known oligomer states and pharmacokinetics for testing absorption variability [4] [2]. |

| Cytokine Panels (ELISA/MSD) | Multiplex assays to quantitatively profile key inflammatory markers (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, TGF-β) in tissue homogenates or perfusates. |

| Histology Stains (H&E, Trichrome) | For visualizing and scoring immune cell infiltration (H&E) and collagen deposition/fibrous capsule thickness (Trichrome) around explanted catheters. |

| FKPP Equation & Computational Models | A mathematical framework for simulating population dynamics of cells (immune) or bacteria on catheter surfaces and in surrounding tissues [20]. |

Advanced Methodologies for Analyzing and Predicting Insulin Pharmacokinetics

In Vivo Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) Studies in Animal Models

In vivo Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) studies are fundamental in drug discovery and development, bridging preclinical research and clinical application. These studies characterize the complex relationship between a drug's concentration in the body (pharmacokinetics, or PK) and its resulting biological effect (pharmacodynamics, or PD). Within the specific context of subcutaneous (SC) insulin absorption research, understanding and managing the inherent physiological delays is a central challenge. This technical support center provides detailed troubleshooting guides, frequently asked questions (FAQs), and standardized protocols to assist researchers in designing, executing, and interpreting robust in vivo PK/PD studies, with a particular focus on overcoming variability and delays in SC drug delivery.

Core Concepts and Quantitative Data

Key PK/PD Parameters in SC Insulin Research

The following parameters are critical for evaluating the performance of insulin formulations and understanding absorption delays.

| Parameter | Definition & Significance in SC Insulin Research |

|---|---|

| AUC (Area Under the Curve) | Total drug exposure over time. For insulin, it correlates with the overall glucose-lowering effect [21]. |

| C~max~ (Maximum Concentration) | The peak plasma drug concentration. A higher C~max~ for insulin indicates a faster onset of action [21]. |

| T~max~ (Time to C~max~) | The time to reach peak concentration. A shorter T~max~ is a key goal for rapid-acting insulins [21]. |

| Onset of Action | The time until a measurable pharmacological effect begins. For insulin, this is the start of blood glucose reduction [22]. |

| Absorption Rate Constant (k~a~) | Quantifies the rate of drug absorption from the SC tissue into the systemic circulation. It is a primary source of variability [2]. |

| Half-life (t~1/2~) | The time for the drug concentration to reduce by half. SC administration significantly extends insulin's half-life compared to intravenous delivery [22]. |

Understanding the properties of different insulin types is essential for study design.

| Insulin Category | Example Products | Time to Onset (min) | Peak Action (h) | Duration (h) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid-Acting | Insulin aspart (NovoLog/NovoRapid), Insulin lispro (Humalog), Insulin glulisine (Apidra) [2] | 10 - 30 [22] | 1 - 3 [22] | 3 - 5 | Amino acid modifications reduce oligomer formation, enabling faster absorption [22]. |

| Short-Acting | Human insulin (Novolin R, Humulin R) [2] | 30 - 60 | 2 - 4 | 5 - 8 | Unmodified human insulin; exists as hexamers that must dissociate before absorption [2]. |

| Intermediate-Acting | NPH insulin (Novolin N, Humulin N) [2] | 1 - 3 | 4 - 10 | 10 - 16 | Protamine-based formulation designed to delay absorption and prolong effect. |

| Long-Acting | Insulin detemir (Levemir) [2] | 1 - 3 | Relatively flat | 12 - 24 | Acylation of the molecule promotes reversible albumin binding, slowing distribution and absorption [2]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Protocol for a Preclinical SC Insulin PK/PD Study

This protocol outlines a generalized methodology for evaluating the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a novel insulin formulation in an animal model, such as mice.

1. Study Design and Animal Preparation

- Model Selection: Use healthy or diabetic animal models (e.g., mice or rats). For cancer-related studies, tumor-bearing mice are also utilized [23].

- Grouping and Dosing: Assign animals to experimental groups (e.g., control, test formulation). Conduct single-dose or multiple-dose studies for up to 3 weeks [23]. Administer insulin via SC route (other common routes include intravenous, intraperitoneal, and oral) [23].

- Fasting: Fast animals for a specified period (e.g., 4-6 hours) prior to the study to establish a baseline glucose level.

2. Sample Collection

- Blood/Plasma for PK: Serial blood samples are collected at predetermined time points (e.g., pre-dose, 5, 15, 30, 60, 120, 180, 240 minutes post-dose) into tubes containing anticoagulants like EDTA or heparin. Plasma is separated by centrifugation [23].

- Blood for PD (Glucose): Concurrently with PK sampling, measure blood glucose levels using a glucose meter or from the plasma samples.

- Tissue for PD (Optional): At the study endpoint, SC tissue from the injection site or other organs can be isolated for biomarker analysis (e.g., Western Blotting, qPCR, Immunohistochemistry) to understand target engagement [23].

3. Bioanalysis

- Sample Preparation: Techniques like Protein Precipitation and Liquid-Liquid Extraction are used to isolate insulin and metabolites from the plasma matrix [23].

- Substance Identification and Quantification: Analysis is typically performed using highly sensitive systems like LC-MS/MS (e.g., TSQ Quantum LC-MS/MS Systems) or high-resolution mass spectrometers (e.g., Orbitrap Q-Exactive LC-MS System) [23].

4. Data Analysis and Reporting

- PK Parameter Calculation: Use specialized software to calculate key PK parameters from the plasma concentration-time data, including AUC, C~max~, T~max~, and half-life [21] [24] [25].

- PD Parameter Calculation: Analyze the glucose-lowering effect, determining parameters like the maximum glucose reduction and the time to achieve it.

- PK/PD Modeling: Integrate PK and PD data to model the relationship between insulin concentration and effect, using software tools for non-compartmental, compartmental, or population modeling [21] [26].

- Deliverables: A final report includes animal weight and behavior, a graphical presentation of the concentration-time and effect-time curves, and the calculated PK parameters [23].

Workflow: In Vivo SC Insulin PK/PD Study

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of a standard preclinical PK/PD study for subcutaneous insulin.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and software for conducting in vivo PK/PD studies on SC insulin absorption.

| Tool / Reagent | Function in SC Insulin Research |

|---|---|

| Rapid-Acting Insulin Analogues (e.g., Insulin aspart, lispro) | The test articles for studying accelerated absorption profiles. Their modified molecular structure reduces self-association into hexamers [22]. |

| Vasoactive Additives (e.g., Treprostinil, Niacinamide) | Research reagents used in novel formulations (e.g., Lyumjev, Fiasp) to increase local SC blood flow, thereby accelerating insulin absorption [22]. |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Gold-standard instrumentation for the sensitive and specific bioanalysis of insulin concentrations in complex biological matrices like plasma [23]. |

| Phoenix WinNonlin | Industry-standard software for performing noncompartmental analysis (NCA) and PK/PD modeling of preclinical and clinical data [21]. |

| SimBiology (MATLAB) | An environment for PK/PD modeling that allows for the creation of complex, mechanistic models, including PBPK models for insulin [24]. |

| Alzet Osmotic Pumps | Miniature implantable pumps used for continuous SC drug delivery in animal models, useful for studying basal insulin kinetics [23]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

This section addresses common experimental challenges in SC insulin PK/PD research.

Problem 1: High Variability in Insulin Absorption Rates

Question: We are observing high inter- and intra-animal variability in the absorption profiles (AUC, C~max~) of our SC insulin formulation. What could be the cause?

Potential Cause 1: Injection Site and Technique.

- Solution: Standardize the injection protocol. Ensure all injections are performed by a trained individual, using a consistent anatomical site (e.g., abdomen typically has fastest absorption) [22], needle size, and injection depth. Avoid repeated injections in the same spot.

Potential Cause 2: Physiological Factors at the Injection Site.

- Solution: Control for factors that influence local blood flow. Maintain a stable ambient temperature for all animals. Avoid procedures that drastically alter skin temperature or blood flow immediately before or after dosing. Account for individual animal factors like age and body composition (obesity can slow absorption) [2] [22].

Potential Cause 3: Insulin Formulation Stability.

- Solution: Ensure the insulin formulation is handled and stored correctly according to manufacturer specifications. Agitation or temperature fluctuations can alter the oligomeric state of insulin, affecting its absorption kinetics [2].

Problem 2: Delayed Onset of Action

Question: The onset of action for our novel rapid-acting insulin candidate is still too slow to effectively control post-meal glucose spikes. How can we investigate this?

Potential Cause 1: Slow Dissociation of Insulin Oligomers.

- Solution: Investigate formulation excipients that shift the oligomeric equilibrium toward monomers. Excipients like citrate (in Lyumjev) and niacinamide (in Fiasp) promote the dissociation of insulin hexamers into smaller, more readily absorbed units [22].

Potential Cause 2: Limited Local Subcutaneous Blood Flow.

- Solution: Explore co-administration with vasodilators. As a research approach, micro-doses of vasoactive agents like glucagon or treprostinil can be tested to increase local blood flow and passively enhance insulin absorption from the SC depot [22].

Potential Cause 3: Injection Volume.

- Solution: Optimize the injection volume. While concentrated formulations are desirable, very large volumes may form a depot that absorbs more slowly. Test different volumes to find the optimal surface-to-volume ratio for rapid dispersion and absorption [22].

Problem 3: Disconnect Between PK and PD Data

Question: We see a good PK profile (rapid absorption), but the glucose-lowering effect (PD) is delayed or blunted. How can we resolve this disconnect?

Potential Cause: Development of Anti-Insulin Antibodies.

- Solution: Analyze plasma samples for the presence of anti-insulin antibodies. In chronic studies, antibodies can bind to the administered insulin, reducing its bioavailable concentration and blunting the PD effect, even if the total plasma concentration appears adequate [22].

Potential Cause: Physiological Counter-Regulation.

- Solution: In diabetic animal models, monitor counter-regulatory hormones like glucagon and epinephrine. A stress response in the animal can trigger the release of these hormones, which oppose the action of insulin and can mask its glucose-lowering effect.

Potential Cause: Inadequate PK/PD Modeling.

- Solution: Employ more sophisticated PK/PD modeling techniques. Instead of simple direct-effect models, use an indirect response model or a link model that incorporates a "effect compartment" to account for the temporal delay (hysteresis) between plasma concentration and pharmacological effect [26].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is there such a significant delay in the action of insulin after subcutaneous injection compared to intravenous administration?

The delay is primarily due to the need for insulin to be absorbed from the SC tissue into the bloodstream. Upon injection, insulin exists primarily as hexamers (large, stable complexes). Before absorption into capillaries, these hexamers must dissociate into smaller dimers and monomers, a time-consuming process. When administered intravenously, insulin bypasses this absorption step and is delivered directly into the circulation, resulting in an almost immediate effect [2] [22].

Q2: What are the most critical physiological factors in the subcutaneous tissue that affect insulin absorption?

The structure and physiology of the SC tissue are major determinants [2]:

- Extracellular Matrix (ECM): Insulin must navigate through a gel-like network of proteins (e.g., collagen) and glycosaminoglycans, which can bind to insulin and act as a reservoir.

- Blood Flow: The rate of local capillary blood flow is a key driver of absorption. Vasodilation increases absorption, while vasoconstriction slows it down.

- Lymphatic System: Larger insulin oligomers (hexamers) and formulations may be partially absorbed via the lymphatic system, which is a slower process than direct capillary uptake.

Q3: How can PK/PD modeling help in the development of better insulin formulations?

PK/PD modeling is a powerful tool that moves beyond descriptive analysis to predictive insights [26]. It can:

- Optimize Molecular Design: Predict how changes to the insulin molecule (e.g., creating analogues) will affect its binding affinity, oligomerization, and ultimately its absorption profile.

- Inform Dosing Strategies: Simulate different dosing regimens to predict which will provide the most optimal glucose control with the lowest risk of hypoglycemia.

- Translate from Preclinical to Clinical: Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models can help translate findings from animal models to humans, de-risking and accelerating clinical development.

Q4: What software tools are available for analyzing PK/PD data from our animal studies?

Several established software platforms are available:

- Phoenix WinNonlin: The industry gold-standard for noncompartmental analysis (NCA) and PK/PD modeling, trusted by regulators worldwide [21].

- SimBiology (MATLAB): Provides a flexible environment for building and fitting both classic and mechanistic PK/PD models, with strong visualization tools [24].

- PKMP: A comprehensive software solution that covers PK, PD, dissolution, and bioequivalence analysis [25].

- R-based tools: Open-source packages (e.g.,

nlmixr,PKPDsim) are also available for PK/PD analysis, offering high flexibility [27].

Signaling Pathway: Mechanism of Accelerated SC Insulin Absorption

The diagram below illustrates the key mechanisms by which novel formulations and co-administration strategies work to accelerate the absorption of subcutaneously administered insulin.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the key advantage of using micro-CT over medical CT scanners for imaging insulin injection depots? Micro-CT provides significantly higher resolution, in the micrometer (µm) range, compared to the millimeter resolution of medical CT scanners. This allows for non-destructive, 3D visualization and analysis of the microscopic structure and dispersion of an insulin depot within the subcutaneous tissue [28] [29].

Q2: How can I determine if my sample is suitable for micro-CT imaging? Micro-CT is ideal for samples that require non-destructive 3D analysis. Consider the following:

- Resolution Needs: Standard micro-CT resolves features from submicron to submillimeter. If you need resolution under 500 nm, a nano-CT system may be required [30].

- Sample Size and Density: The sample must fit in the scanner and not be too dense for X-rays to penetrate. High-density or large samples may require a higher-energy X-ray source [30].

- Density Contrast: The technique relies on variations in X-ray absorption. If there is insufficient natural density contrast within your sample, you may need to use a contrast agent (e.g., iomeprol) to stain the insulin [13] [30].

Q3: Why is the injection depth critical in subcutaneous insulin absorption studies? The depth of injection directly influences the rate of insulin absorption. Intramuscular injections (into the muscle) result in faster and more variable insulin absorption compared to true subcutaneous injections (into the fatty tissue). This is a major source of pharmacokinetic variability and can be influenced by needle length and the thickness of the subcutaneous fat layer [4] [31].

Q4: What physiological factors can alter insulin absorption from a subcutaneous depot? Multiple factors can influence absorption kinetics [2] [4]:

- Obesity/Adipose Tissue Thickness: Increased fat mass is correlated with delayed insulin absorption and slower depot disappearance [13].

- Local Blood Flow: Factors that increase blood flow, such as local warming or exercise, can accelerate insulin absorption [4].

- Injection Site: Absorption rates can vary between different injection areas (e.g., abdomen, thigh, arm).

- Tissue Health: Lipodystrophy (scarring or hardening of tissue) can impair and highly variate insulin absorption [32].

Troubleshooting Common Micro-CT Experimental Issues

General Micro-CT Setup and Imaging

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Resolution [30] | Incorrect scanner capability or setup parameters. | Verify scanner specifications. Adjust measurement conditions (e.g., magnification, detector position) to maximize resolution. For features under 500nm, consider nano-CT. |

| Sample doesn't fit Field of View (FOV) [30] | Sample is larger than the scanner's maximum FOV. | Scan only the area of interest. Use scanner stitching, helical, or offset scan modes if available. |

| Image is too dark [30] | Sample is too dense or X-ray energy is too low; not enough X-rays penetrate. | Increase the X-ray voltage (kV). Use heavier X-ray filters to harden the beam. Reduce sample size if possible. |

| Image is too bright with no contrast [30] | Sample has low density or X-ray energy is too high; most X-rays pass through. | Lower the X-ray voltage. Use an X-ray source with a metal anode (e.g., Chromium) that emits lower-energy characteristic radiation. |

| Long Scan Times [30] | Trade-off between resolution, signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), and speed. | Adjust scan conditions. Accept a lower resolution or SNR for faster scans. For very high-throughput needs, 2D radiography may be a better alternative. |

| Large File Sizes [30] | High-resolution 3D datasets are inherently large. | Crop or down-sample images during analysis. Invest in adequate data storage solutions (NAS, cloud storage). |

Specific Challenges in Insulin Depot Imaging

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Depot Contrast [13] [32] | Lack of sufficient X-ray absorption difference between insulin and adipose tissue. | Mix insulin with a radio-opaque contrast agent like iomeprol to enhance visualization of the depot [13]. |

| High Variability in Depot Morphology [32] | Incorrect injection depth; natural anatomical variations in subcutaneous tissue. | Confirm catheter placement in the hypodermis during experimental setup. Use a sufficient sample size to account for biological variability. |

| Unexpected Pressure Alerts/Occlusions [32] | Air bubbles in the infusion line; catheter kinking or blockage. | Meticulously purge all air from the infusion system before starting. Use in-line pressure sensors to monitor for occlusions in real-time. |

| Depot Disappearance Kinetics do not correlate with PK data [13] | Alterations in subcutaneous tissue structure (e.g., due to obesity). | Ensure body composition (fat mass) is accounted for as a covariate in the study design. Larger, more dispersed depots (higher surface-to-volume ratio) generally correlate with faster absorption [13] [32]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Experiments

Protocol: In Vivo Visualization of Insulin Depot Kinetics using μCT

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating the link between obesity and delayed insulin absorption [13].

1. Objective: To visualize and quantify the formation and disappearance of a subcutaneous insulin injection depot in vivo and correlate it with pharmacokinetic exposure.

2. Materials:

- Animals: Diet-induced obese (e.g., High-Fat Diet fed) and lean control (e.g., Low-Fat Diet fed) rodent models.

- Insulin Formulation: Rapid-acting insulin analog (e.g., Insulin Aspart).

- Contrast Agent: Iomeprol (350 mg I/mL).

- Micro-CT Scanner: e.g., Quantum XT (PerkinElmer).

- Anesthesia System: Isoflurane vaporizer.

- Blood Collection System: For serial sampling from tail or sublingual vein.

- Immunoassay Kit: For plasma insulin quantification (e.g., Luminescent Oxygen Channelling Immunoassay).

3. Methodology:

- Preparation: Anesthetize the rat and place it in the scanner. Mix insulin aspart with iomeprol in an 80/20 ratio.

- Dosing and Imaging: Administer the insulin-contrast mixture subcutaneously (e.g., 20 µL in the neck or flank). Immediately initiate sequential μCT scans at predetermined time points (e.g., 1, 3, 7, 13, and 17 minutes post-dosing).

- Pharmacokinetic Sampling: Collect blood samples at key time points (e.g., 5, 15, 60 min) to measure plasma insulin concentrations.

- Data Analysis:

- Image Analysis: Use 3D imaging software (e.g., Imaris, Bitplane) to segment the depot and calculate its Volume and Surface Area at each time point.

- Kinetic Analysis: Calculate the rate of depot disappearance over time.

- Statistical Analysis: Use a mixed-model analysis to compare depot kinetics and insulin exposure (AUC, C~max~) between diet groups, with day and rat as random factors.

In Vivo μCT Workflow for Insulin Depot Kinetics

Protocol: Ex Vivo Assessment of Continuous Insulin Infusion

This protocol is based on a method developed to study basal rate insulin pump delivery in human tissue [32].

1. Objective: To objectively assess the spatial dispersion of insulin during continuous low-rate subcutaneous infusion in real-time.

2. Materials:

- Tissue: Human skin explants (e.g., abdominal tissue from surgery) with intact epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis.

- Infusion System: Insulin pump (e.g., Tandem t:slim), catheter, and tubing.

- Infusate: Insulin mixed with contrast agent.

- Micro-CT Scanner

- Pressure Sensors: Microfluidic sensors integrated into the infusion line.

- Analysis Software: For image segmentation and calculation of dispersion metrics.

3. Methodology:

- Setup: Mount the skin explant in the μCT scanner. Insert the pump catheter into the explant, targeting the hypodermis. Connect the catheter to the pump via the pressure sensors.

- Infusion and Imaging: Set the pump to a basal rate (e.g., 1 U/h). Initiate the scan, acquiring one 3D image every 5 minutes for 3 hours. Simultaneously, record pressure data from the infusion line.

- Data Analysis:

- Segmentation: For each 3D image, segment the voxels containing the insulin-contrast depot.

- Calculate Index of Dispersion (IoD): For each time point, compute this index to quantify how dispersed the depot is compared to a perfect sphere [32]:

- Measure the depot's surface area (S~measured~(t)) and volume (V~measured~(t)).

- Calculate the surface area of a sphere with the same volume (S~compact~(t)).

- IoD(t) = S~measured~(t) / S~compact~(t)

- A higher IoD indicates a more dispersed depot, which is theorized to facilitate faster absorption.

Ex Vivo Basal Infusion Analysis Workflow

| Parameter | High-Fat Diet (HFD) Group (Mean ± SEM) | Low-Fat Diet (LFD) Group (Mean ± SEM) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body Weight (30 weeks) | 777 ± 13 g | 658 ± 20 g | < 0.05 |

| Fat Mass | Significantly increased | Baseline | < 0.001 |

| Insulin Concentration (15 min post-dosing) | Significantly lower | Higher | < 0.001 |

| AUC₀–₆₀ min | Significantly reduced | Higher | < 0.01 |

| Injection Depot Volume | Smaller | Larger | < 0.05 |

| Depot Disappearance Rate | Slower | Faster | < 0.05 |

| Parameter | Typical Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | 0.5 µm - 150 µm | Sub-micron is Nano-CT territory [28] [29]. |

| Sample Size | Up to 200 mm diameter | Depends on specific scanner model [29]. |

| Scan Time | Several seconds to tens of hours | Trade-off with resolution and signal-to-noise [30]. |

| X-ray Source Voltage | Up to 240 kV (or higher) | Higher voltage for denser samples [28] [30]. |

| Comparative Resolution (Medical CT) | ~1 mm | Micro-CT provides significantly higher detail [29]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Insulin Aspart (NovoRapid) | A rapid-acting insulin analog used as the test molecule for studying absorption kinetics [13]. |

| Iomeprol (Iomerol 350) | A radio-opaque contrast agent mixed with insulin to make the injection depot visible under X-ray/μCT [13]. |

| Luminescent Oxygen Channelling Immunoassay | A sensitive biochemical method for the quantitative measurement of plasma insulin concentrations in pharmacokinetic studies [13]. |

| High-Fat / Low-Fat Diets (Research Diets) | Used to generate animal models of obesity and leanness to study the effect of body composition on insulin absorption [13]. |

| Human Skin Explants (Abdominal) | Provide an ex vivo model using human tissue to study insulin dispersion and infusion dynamics in a controlled setting [32]. |

| Micro-Fluidic Pressure Sensors | Integrated into infusion lines to monitor pressure in real-time, detecting occlusions or flow resistance during insulin pump studies [32]. |

| Imaris Software (Bitplane) | A advanced 3D/4D image visualization and analysis software used for segmenting the insulin depot and quantifying its volume and surface area [13]. |

Computational and Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling of Absorption Processes

Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Reagents and Materials for PBPK Model Development of Subcutaneous Insulin Absorption

| Item Name | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Commercial PBPK Software (e.g., Simcyp, GastroPlus, PK-Sim) | Platforms that provide integrated physiological databases and implement PBPK modeling approaches for parametrizing a whole-body model [33]. |

| Insulin Formulations (Monomeric, NPH, Glargine, etc.) | Different insulin types have distinct oligomerization states and absorption kinetics, requiring specific model parameters for accurate simulation [34] [2]. |

| Recombinant Human Hyaluronidase | An enzyme that degrades hyaluronan in the extracellular matrix; used in experiments to study and model the impact of matrix barriers on absorption [35]. |

| Physiological Data Compilations | Prior knowledge on organ volumes, blood flows, tissue composition, and lymph flow rates is essential for populating the system parameters of the PBPK model [33]. |

| In Vitro-In Vivo Extrapolation (IVIVE) Tools | Methods to quantify organ-level clearance from in vitro metabolism data, which is a key input for modeling active processes in PBPK [33]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: Our PBPK model consistently underestimates the plasma concentration of a subcutaneously administered monoclonal antibody in the first few hours. What could be the cause?

- Answer: This is a common challenge, often related to the model's representation of the initial absorption phase. Key factors to investigate are:

- Lymphatic Uptake: For large molecules like mAbs, systemic absorption occurs primarily via the lymphatic system, not blood capillaries. Ensure your model correctly incorporates afferent lymph flow from the injection site and accounts for the time the drug spends traversing the lymphatic network before reaching systemic circulation [36].

- Pre-systemic Clearance: A fraction of the administered dose can be catabolized locally before reaching the blood. For mAbs, this can occur in antigen-presenting cells (e.g., macrophages) within the draining lymph nodes via the FcRn salvage pathway. Model this clearance by incorporating endocytosis and FcRn binding parameters in the lymph node compartment [36].

- Injection Site Volume: The assumed volume of the SC injection site can be arbitrary. Use physiological data, such as the travel distance of labeled albumin to sentinel lymph nodes, to estimate a more accurate injection site volume, which influences initial drug concentrations and absorption rates [36].

FAQ 2: How can we model the high inter- and intra-individual variability observed in subcutaneous insulin absorption profiles?

- Answer: Variability is a hallmark of SC absorption and can be incorporated into your PBPK model by accounting for its known sources:

- Physiological Variability: Key parameters like subcutaneous blood flow are not static. Model them as dynamic variables influenced by "life events" such as exercise, local temperature, food intake, and stress, all of which significantly impact absorption rates [2] [35].

- Injection Factors: The model can incorporate the impact of injection site (arm, abdomen, thigh, back), which have different blood flow rates, lymph flow, and tissue density [36] [2]. Furthermore, factors like injection depth, volume, and potential formulation backflow can be included as sources of variability [35].

- Tissue Properties: Disease states like Type 2 Diabetes or obesity can alter the physiology of the subcutaneous tissue, including capillary density and extracellular matrix composition. Parameterize your model for these specific populations to account for this structured variability [35].

FAQ 3: We are developing a model for a new long-acting insulin analogue. What are the critical drug-specific parameters we need to consider?

- Answer: Moving beyond human insulin requires modeling the specific protraction mechanisms of modern analogues.

- Oligomerization Kinetics: The model must describe the dissociation of insulin oligomers (hexamers → dimers → monomers). For analogues like insulin glargine, this involves modeling precipitation at the neutral pH of the SC tissue and subsequent slow dissolution [34].

- Albumin Binding: For acylated analogues (e.g., insulin detemir), the model needs to include their binding to albumin in the SC tissue and plasma, which is a major mechanism for prolonging the half-life. This requires parameters for binding affinity and rates [2].

- Dose/Concentration Dependency: The absorption kinetics of some insulins are nonlinear with respect to dose and concentration. Ensure your model structure can capture this dependency, which is often handled with saturable transport or dissolution processes [34].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Parameterizing a Unified Compartmental Model for Multiple Insulin Types

This methodology is based on the work by et al. (2008) to develop a single model for rapid-acting, regular, NPH, lente, ultralente, and glargine insulin [34].

- Data Collection: Conduct an extensive literature review to collect mean plasma insulin time-course data from clinical studies for each insulin type. The study referenced 37 such datasets [34].

- Model Structure Definition: Implement a compartmental model that represents key physiological states.

- Compartments: Include states for hexameric, dimeric/monomeric insulin, and specific compartments for insulin crystals (NPH, lente) or precipitated insulin (glargine) [34].

- Mass Transfer: Define first-order rate constants (

k1,k2) for the dissociation of hexamers to dimers/monomers and absorption into plasma. Include rate constants for crystal dissolution (kcrys) and local degradation (kd) [34].

- Parameter Identification: Use nonlinear optimization methods to fit the model parameters to the collected time-course data. The model's ability to describe diverse insulin types with a single set of identifiable parameters (coefficient of variation < 100%) should be validated [34].

Protocol 2: Implementing a Mechanistic Subcutaneous Injection Site Model

This protocol outlines the steps for building a physiologically based injection model as described in the SubQ-Sim framework [35].

- Define System Parameters: Parameterize the subcutaneous adipose tissue for your target population.

- Anatomy: Define tissue thickness, fractional volumes for blood (capillaries), interstitial fluid, and cells based on anatomical region and Body Mass Index (BMI) [35].

- Dynamics: Set baseline values for subcutaneous blood flow and afferent lymph flow, ensuring they can be modulated by "life events" [35].

- Simulate Injection and Depot Formation:

- Inputs: Specify injection parameters: volume, rate, solution viscosity, and needle size.

- Outputs: The model calculates tissue back-pressure during injection, predicts the shape and dimensions of the formed depot, and estimates potential formulation loss due to backflow [35].

- Incorporate Absorption Pathways:

- For small molecules/insulins, model distribution through the interstitial space and primary absorption into venous capillaries.

- For large molecules/mAbs, model the primary absorption pathway via the lymphatic capillaries, flow through draining lymph nodes, and eventual delivery to systemic circulation via the thoracic duct [36] [35].

Data Presentation: Key Parameters for Subcutaneous PBPK Modeling

Table: Quantitative Parameters for Modeling Subcutaneous Insulin and mAb Absorption

| Parameter | Description | Typical Value / Range | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| SC Tissue Blood Flow | Blood perfusion rate of adipose tissue. | 2.9 - 9.2 mL/min/100g (varies by site) [36] | A key driver of absorption for small proteins and insulin. |

| Afferent Lymph Flow | Flow rate from interstitium into initial lymphatics. | ~4.8 x 10⁻⁵ L/h (from arm/back) [36] | Critical parameter for monoclonal antibody (mAb) absorption. |

| Number of Draining Lymph Nodes | Number of lymph nodes a mAb traverses before systemic circulation. | 18 - 36 nodes (varies by injection site) [36] | Impacts the time delay and pre-systemic clearance for mAbs. |

| Fractional Interstitial Fluid Volume | Volume fraction of interstitial fluid in adipose tissue. | ~0.10 [35] | Defines the distribution space in the extracellular matrix. |

Hexamer → Dimer/Monomer Rate (k1) |

First-order rate constant for insulin dissociation. | Fitted parameter (CV < 100% in a unified model) [34] | Core parameter defining the absorption rate of soluble insulins. |

Model Workflow and Physiological Pathways

Diagram: PBPK Model Workflow for SC Absorption

Diagram: Physiological Pathways at the Injection Site

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the practical difference between intra- and inter-subject variability in pharmacokinetics? Inter-subject variability refers to the differences in drug concentration profiles between different individuals, while intra-subject variability refers to the differences observed from one dosing occasion to another within the same individual [37] [2]. For example, a study on indoramin found inter-subject coefficients of variation (C.V.) for Cmax and AUC were circa 100%, whereas intra-subject C.V. were around 20% [37]. High inter-subject variability means the same dose can produce vastly different exposures in different people, complicating initial dose finding. High intra-subject variability means a patient's response to the same dose is unpredictable from day to day, complicating daily management.