Intestinal Glucose Transport: Unraveling the Critical Roles and Therapeutic Targeting of SGLT1 and GLUT2

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the sodium-glucose cotransporter SGLT1 and the facilitative glucose transporter GLUT2 in intestinal glucose absorption, a process critical for systemic energy homeostasis.

Intestinal Glucose Transport: Unraveling the Critical Roles and Therapeutic Targeting of SGLT1 and GLUT2

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the sodium-glucose cotransporter SGLT1 and the facilitative glucose transporter GLUT2 in intestinal glucose absorption, a process critical for systemic energy homeostasis. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational physiology, advanced research methodologies, and contentious mechanistic debates. The scope spans from the established role of SGLT1 in active apical uptake and incretin secretion to the controversial apical recruitment of GLUT2 under high glucose loads. It further explores how these pathways are investigated, modulated by dietary and pharmacological agents, and leveraged in developing therapeutic strategies for diabetes and metabolic disorders. The content integrates recent findings, including the role of paracellular transport and the effects of compounds like dexamethasone and oat β-glucan, to offer a state-of-the-art perspective on the field.

The Core Machinery: Defining SGLT1 and GLUT2 in Intestinal Glucose Physiology

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1) serves as the principal apical membrane transporter responsible for active glucose uptake in the intestine. This whitepaper consolidates current understanding of SGLT1's molecular mechanism, regulation, and functional interplay with the basolateral facilitator GLUT2. We present quantitative data on transport kinetics, detailed experimental methodologies for investigating transporter function, and visualization of key pathways. Within the broader framework of intestinal glucose absorption research, this resource provides scientists and drug development professionals with technical insights into the core transporter that enables active transcellular glucose flux, a process fundamental to energy homeostasis and a target for therapeutic intervention.

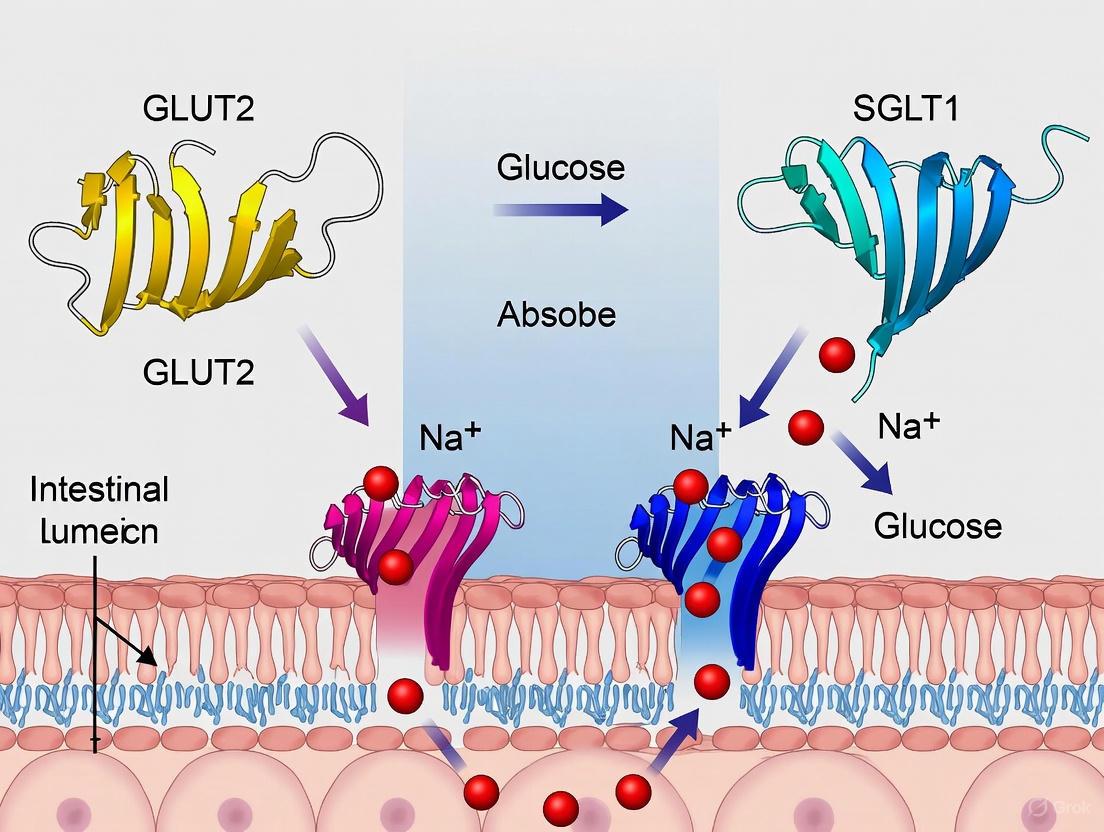

The absorption of dietary glucose across the intestinal epithelium is a critical process for maintaining systemic energy balance. The prevailing model involves a two-step transcellular pathway: first, active uptake across the apical membrane of enterocytes, and second, facilitated efflux across the basolateral membrane into circulation [1]. SGLT1 (SLC5A1) is unequivocally established as the primary mediator of the initial, rate-limiting apical step [1] [2]. This transporter harnesses the electrochemical sodium gradient maintained by the basolateral Na+/K+ ATPase to drive the uphill transport of glucose and galactose into the cell against their concentration gradients [1] [2].

The functional partnership between SGLT1 and the basolateral transporter GLUT2 (SLC2A2) is essential for complete transcellular absorption [3] [4]. While SGLT1 performs active, concentrative uptake, GLUT2 provides a high-capacity pathway for the facilitated diffusion of glucose out of the enterocyte [4]. However, emerging evidence complicates this classic division of labor, suggesting that GLUT2 can be rapidly recruited to the apical membrane under high luminal glucose loads, contributing to a diffusive absorption component [3]. This whitepaper delves into the specific role of SGLT1 within this dynamic system, detailing its structure, function, and the experimental evidence that defines it as the primary apical workhorse for active glucose uptake.

Molecular Mechanism and Structural Basis of SGLT1

SGLT1 is a high-affinity, low-capacity glucose transporter with a coupling stoichiometry of 2 Na+ ions per 1 glucose molecule [2]. Recent cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structures have elucidated the atomic-level details of its operation.

Architecture and Transport Cycle

The structure of human SGLT1 reveals a core of 14 transmembrane helices (TM0-TM13) that adopt a leucine transporter (LeuT) fold [2]. A distinctive extracellular domain, or "lid," formed by loops EL3, EL4, and EL6, covers the extracellular surface and is stabilized by multiple disulfide bonds critical for folding and function [2]. The transport cycle involves alternating between outward-open and inward-open conformations. In the outward-open state, the extracellular gate is accessible, allowing Na+ ions to bind first, which induces a conformational change that increases affinity for glucose. Following glucose binding, the protein transitions to an inward-open state, releasing both substrates into the cytoplasm before returning to the outward-open state to begin a new cycle [2].

Inhibitor Binding and Specificity

The structural mechanism of SGLT1 inhibition is exemplified by the inhibitor LX2761, which locks the transporter in an outward-open conformation [5]. The glucose-mimetic ring of LX2761 occupies the sugar-binding site, forming hydrogen bonds with residues Asn78 (TM1), Glu102 (TM2), and Lys321 (TM7). Its aglycon tail extends into the extracellular vestibule, making extensive hydrophobic interactions [5]. This detailed understanding of the inhibitor-binding pocket enables the rational design of selective therapeutic compounds.

The diagram below illustrates the core structure and conformational states of the SGLT1 transporter.

Quantitative Functional Data and Transport Kinetics

Experimental data from vascularly perfused rat intestine models and cell-based assays provide quantitative insights into SGLT1's contribution to total glucose absorption and its kinetic properties.

Table 1: Glucose Absorption in Isolated, Vascularly Perfused Rat Intestine Model [6]

| Luminal Glucose Concentration | Total Glucose Absorption (μmol/15 min) | Effect of SGLT1 Blockade (Phlorizin) |

|---|---|---|

| 1% (55 mmol/L) | 51.6 ± 4.2 | Data not reported for this concentration |

| 5% (278 mmol/L) | 88.3 ± 5.6 | Data not reported for this concentration |

| 10% (550 mmol/L) | 193.1 ± 14.7 | Data not reported for this concentration |

| 20% (1100 mmol/L) | 616.7 ± 78.2 | Data not reported for this concentration |

| 100 mmol/L | ~430 (First stimulation) | Reduced by ~60% (to ~184 μmol/15 min) |

Table 2: Impact of Transporter Blockade on Glucose Absorption [6]

| Experimental Intervention | Target | Glucose Absorption Change | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luminal Phlorizin (at 100 mmol/L glucose) | Apical SGLT1 | ~60% reduction | SGLT1 mediates majority of uptake at this concentration |

| Intra-arterial Phloretin (at 100 mmol/L glucose) | Basolateral GLUT2 | ~70-80% reduction | GLUT2 is critical for basolateral glucose efflux |

| Combined SGLT1 & GLUT2 Blockade | Both pathways | ~30% of absorption remained | Suggests additional pathways (e.g., paracellular) |

The data in Table 1 demonstrates that intestinal glucose absorption is non-saturable under high luminal glucose loads, hinting at the involvement of additional, non-active pathways. The blockade studies in Table 2 quantitatively establish SGLT1's primary role, while also revealing a significant residual absorption component (~30%) that persists even after combined SGLT1/GLUT2 inhibition, suggesting a contribution from passive paracellular transport [6].

Key Experimental Models and Methodologies

Investigating SGLT1 function requires specialized experimental models that preserve the polarity and physiological context of the intestinal epithelium.

The Isolated, Vascularly Perfused Rat Intestine

This ex vivo model maintains intact epithelial polarity, vascular perfusion, and enterocyte viability, allowing for precise experimental control and measurement.

Typical Protocol for Glucose Absorption Studies: [6]

- Isolation and Cannulation: A segment of rat jejunum is surgically isolated, and its vascular bed and lumen are cannulated.

- Perfusion: The vasculature is perfused with an oxygenated, buffered solution (e.g., Krebs-Henseleit buffer) containing a macromolecule like dextran to maintain oncotic pressure. The lumen is perfused with a saline solution.

- Luminal Stimulation: The luminal perfusate is switched to a solution containing D-glucose at varying concentrations (e.g., from 55 mmol/L to 1100 mmol/L). Each concentration is typically maintained for 15-30 minutes to reach a steady-state absorption rate.

- Tracer Use and Quantification: Radioactively labeled 14C-D-glucose is added to the luminal perfusate. The appearance of this tracer in the vascular effluent provides a sensitive and accurate measure of absorbed glucose.

- Pharmacological Blockade: To dissect the contribution of SGLT1, the specific inhibitor phlorizin (e.g., 1 μmol/L) is added to the luminal perfusate during a subsequent glucose stimulation period.

- Data Analysis: Glucose absorption is calculated based on the arteriovenous concentration difference of the radioactive tracer and the flow rate of the vascular perfusate.

Differentiated Caco-2/TC7 Cell Monolayers

The human colon carcinoma-derived Caco-2/TC7 cell line, when cultured on permeable filters, spontaneously differentiates to form a polarized monolayer with an apical brush border, resembling small intestinal enterocytes.

Typical Protocol for Glucose Uptake Assays: [7]

- Cell Culture and Differentiation: Caco-2/TC7 cells are seeded onto transwell filters and cultured for at least 21 days to allow full differentiation. The medium is changed regularly.

- Experimental Treatment: Differentiated monolayers are treated with compounds of interest (e.g., dexamethasone to study SGLT1 upregulation) for a specified duration (e.g., 60 hours).

- Glucose Uptake Measurement: Cells are starved in glucose-free medium for a short period (e.g., 4 hours). The uptake assay is initiated by adding a solution containing a non-metabolizable glucose analog (e.g., 2-deoxy-D-glucose) to the apical compartment.

- Inhibition Studies: The SGLT1-specific component of uptake is defined by its sensitivity to phlorizin added to the apical solution.

- Analysis: Cells are lysed, and the accumulated radiolabeled or fluorescent tracer is quantified. Transporter expression (SGLT1, GLUT2 mRNA/protein) is often analyzed in parallel via qPCR or western blot.

The following diagram outlines the workflow for a key methodology used to study SGLT1 function.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Essential pharmacological and molecular tools for probing SGLT1 function in experimental settings are summarized in the table below.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for SGLT1 Research

| Reagent | Type | Primary Target | Mechanism of Action / Use | Key Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phlorizin | Inhibitor | SGLT1 | Competitive inhibitor binding to the glucose site on SGLT1 [6] [1] | Defining SGLT1-mediated component of glucose uptake in functional assays [6] |

| LX2761 | Inhibitor | SGLT1/SGLT2 (Dual) | Locks SGLT1 in an outward-open conformation by wedging into substrate-binding site [5] | Used in structural studies (cryo-EM) to elucidate inhibitor binding mechanism [5] |

| Phloretin | Inhibitor | GLUT2 | Blocks facilitated glucose transport via GLUT2 [6] | Dissecting basolateral glucose efflux; used to probe apical GLUT2 recruitment [6] |

| Dexamethasone | Agonist | Glucocorticoid Receptor | Upregulates SGLT1 mRNA and protein expression [7] | Studying transcriptional regulation of SGLT1 and its functional consequences [7] |

| 2-deoxy-D-glucose | Analogue | - | Non-metabolizable glucose tracer [7] | Accurate measurement of glucose uptake without interference from subsequent metabolism [7] |

| 14C-D-glucose | Tracer | - | Radioactive label for glucose [6] | Sensitive and quantitative tracking of glucose absorption in complex models (e.g., perfused intestine) [6] |

Regulatory Context and Pathophysiological Significance

SGLT1's expression and activity are tightly regulated and implicated in several physiological and disease states, making it a molecule of significant clinical interest.

- Regulation by Luminal Content and Hormones: Intestinal SGLT1 expression is modulated by sweet taste receptors and the presence of luminal glucose, enabling a feedback loop for glucose absorption [1]. Hormones such as GLP-2 can also regulate its expression and membrane trafficking [3]. Dexamethasone, a glucocorticoid, has been shown to dose-dependently increase SGLT1 mRNA and enhance glucose absorption, providing a mechanistic link between steroid therapy and hyperglycaemia [7].

- Genetic Evidence from GGM: The most compelling evidence for SGLT1's non-redundant role comes from Glucose-Galactose Malabsorption (GGM), a rare autosomal recessive disorder caused by loss-of-function mutations in the SGLT1 gene (SLC5A1). This condition results in life-threatening osmotic diarrhea upon ingestion of glucose or galactose, unequivocally demonstrating SGLT1's critical role in intestinal di-saccharide absorption [1] [2].

- Upregulation in Metabolic Disease: In contrast to GGM, conditions like obesity and type 2 diabetes are associated with increased SGLT1 expression in the proximal intestine, potentially contributing to accelerated glucose absorption and postprandial hyperglycaemia [1] [8]. This makes SGLT1 a potential therapeutic target for managing postprandial glucose spikes.

SGLT1 stands as the principal and indispensable apical mediator of active glucose uptake in the intestine. Its well-defined active transport mechanism, coupled with growing understanding of its regulation in health and disease, solidifies its central position in the framework of intestinal glucose homeostasis. While its functional partner GLUT2 and other potential pathways contribute to overall absorption, SGLT1 undertakes the critical energy-dependent step. Ongoing research into its structural biology and regulatory networks continues to inform the development of novel therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating intestinal glucose absorption for improved metabolic health.

In the established model of intestinal glucose homeostasis, the coordinated action of apical sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1) and basolateral glucose transporter 2 (GLUT2) facilitates the efficient transfer of dietary glucose into the systemic circulation. While SGLT1 mediates the active uptake of glucose from the intestinal lumen into the enterocyte, GLUT2 serves as the primary conduit for its passive, facilitative diffusion across the basolateral membrane into the blood. This whitepaper delineates the critical role of basolateral GLUT2 in systemic glucose release, synthesizing foundational and contemporary research to present a definitive technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals. The document provides structured quantitative data, experimental protocols for validating GLUT2 function, and visual tools to elucidate these processes, all framed within the ongoing scientific discourse on intestinal glucose handling.

Molecular Mechanisms and Transporter Kinetics

The absorption of dietary glucose is a two-stage process that exemplifies precise epithelial transport coordination. The initial stage involves active transport across the apical (brush-border) membrane of the enterocyte. This is mediated by SGLT1 (SLC5A1), which couples the uphill transport of glucose against its concentration gradient to the downhill movement of sodium ions. The energy for this process is derived from the sodium gradient maintained by the basolateral Na+/K+-ATPase [9] [10].

Once inside the cell, glucose exits across the basolateral membrane into the interstitial fluid and subsequently into the bloodstream via GLUT2 (SLC2A2). This transporter functions as a facilitative uniporter, allowing glucose to move down its concentration gradient from the cell into the blood without energy expenditure [4] [9]. The expression of GLUT2 on the basolateral membrane is constitutive, ensuring a constant pathway for glucose efflux.

The kinetic properties of SGLT1 and GLUT2 are complementary, reflecting their distinct roles. The following table summarizes their key characteristics:

Table 1: Functional Properties of Key Intestinal Glucose Transporters

| Property | SGLT1 (Apical) | GLUT2 (Basolateral) |

|---|---|---|

| Transport Mechanism | Active, secondary transport | Facilitated diffusion |

| Sodium Coupling | 2:1 (Na+:Glucose) [11] | Not sodium-dependent [9] |

| Primary Driving Force | Na+ gradient (maintained by Na+/K+-ATPase) | Glucose concentration gradient |

| Apparent Km for Glucose | ~2-5 mM [11] [9] | ~20-40 mM [4] [9] |

| Substrate Specificity | D-glucose, D-galactose [9] | D-glucose, D-galactose, D-fructose, glucosamine [4] [12] |

| Inhibitors | Phlorizin [13] [9] | Phloretin [9] |

The high affinity (low Km) of SGLT1 is optimized for efficient scavenging of luminal glucose, even at low concentrations. In contrast, the low affinity (high Km) of GLUT2 suits its role as a high-capacity exit pathway, which remains effective even when intracellular glucose concentrations rise postprandially [4]. This kinetic profile prevents the accumulation of glucose to toxic levels within the enterocyte.

Diagram: The Classical Model of Intestinal Glucose Absorption

Key Experimental Evidence and Data

The foundational role of basolateral GLUT2 has been substantiated by genetic, pharmacologic, and tracer studies. Knockout mouse models provide particularly compelling evidence.

- GLUT2-Deficient Mouse Models: Mice with a targeted deletion of the GLUT2 gene (Slc2a2) exhibit impaired glucose tolerance and elevated blood glucose levels following an oral glucose challenge. This is directly attributed to a reduced capacity for glucose efflux from enterocytes into the circulation. Intriguingly, these knockout animals showed higher tracer glucose contents in intestinal tissue after a radiolabeled glucose gavage compared to wild-type controls, indicating a "backing up" of glucose within the enterocytes due to the defective basolateral exit mechanism [13] [14].

- SGLT1 vs. GLUT2 Deletion Phenotypes: The physiological consequences of deleting SGLT1 versus GLUT2 are distinct and highlight their sequential roles. SGLT1 knockout mice show a drastic reduction in intestinal glucose uptake throughout the small intestine and fail to secrete glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) in response to glucose [13] [14]. In contrast, GLUT2 knockout mice have impaired glucose-induced insulin secretion but normal incretin secretion, underscoring GLUT2's primary role in systemic glucose dispersal rather than gut sensing [13].

- Renal Corroboration: The physiological principle of GLUT2-mediated basolateral efflux is conserved in the kidney. In the proximal tubule, glucose reabsorbed by apical SGLT1 and SGLT2 exits the cell into the interstitium via basolateral GLUT2. Mutations in GLUT2 are associated with the Fanconi-Bickel syndrome, characterized by renal glucose loss and hepatorenal glycogen accumulation, confirming its non-redundant role in systemic glucose release [11].

Table 2: Phenotypic Comparison of Glucose Transporter Knockout Models

| Experimental Model | Effect on Intestinal Glucose Uptake | Effect on Blood Glucose | Effect on Hormone Secretion |

|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT1 Knockout | Drastically reduced tissue retention of tracer glucose [13] | Reduced postprandial elevation [13] | Abolished GIP and GLP-1 secretion [13] |

| GLUT2 Knockout | Increased tissue retention of tracer glucose [13] | Impaired clearance, hyperglycemia [13] [4] | Impaired glucose-induced insulin secretion; normal incretin secretion [13] |

Debates and Alternative Viewpoints

A significant controversy in the field involves the potential apical recruitment of GLUT2. Some research posits that high luminal glucose concentrations (>30 mM) trigger the rapid translocation of GLUT2 from cytoplasmic vesicles to the apical membrane, where it may contribute to bulk glucose absorption via facilitated diffusion [9] [15].

However, critical studies using rigorous methodology have challenged this hypothesis. A comparative investigation in knockout mice concluded that SGLT1 is unequivocally the prime intestinal glucose transporter, even at high luminal concentrations. This study found that GLUT2 detected in apical membrane fractions primarily resulted from contamination with basolateral membranes and did not change in abundance after a high-glucose bolus [13] [14]. The weight of evidence suggests that while apical GLUT2 recruitment might occur in specific experimental conditions or disease states (e.g., morbid obesity), its contribution to overall glucose absorption in the healthy intestine under normal physiological conditions is likely minimal compared to the essential, constitutive function of basolateral GLUT2.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

For researchers investigating basolateral GLUT2 function, the following protocols provide a methodological foundation.

Using Chamber Assay for Ileal Glucose Transport

This ex vivo technique directly measures electrogenic glucose transport across intact intestinal tissue [10].

Workflow:

- Tissue Preparation: Euthanize the animal and swiftly excise the distal ileum. Flush with ice-cold Ringer's solution to remove luminal content. Open the intestine along the mesenteric border and mount in an Ussing chamber, exposing the mucosal and serosal surfaces to separate bathing reservoirs.

- Solution Composition: Bathe both sides with oxygenated (95% O₂, 5% CO₂) Ringer's solution at 37°C. The standard solution contains (in mM): 119 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 2.5 CaCl₂, 1.2 MgSO₄, 1.2 KH₂PO₄, 25 NaHCO₃, and 10 glucose (serosal) or mannitol (mucosal) for osmotic balance [10].

- Measurement: After an equilibration period, replace mucosal mannitol with 25 mM D-glucose. The active transport of glucose via SGLT1, coupled with Na+, generates a negative current shift (increase in short-circuit current, Isc) that can be measured. The involvement of GLUT2 can be probed by adding specific inhibitors like phloretin to the serosal side to block basolateral efflux, which will indirectly affect the system.

Oral Gavage of Radiolabeled Glucose with Tissue Analysis

This in vivo approach quantifies glucose uptake and tissue retention [13] [14].

Workflow:

- Animal Preparation: House mice under controlled conditions and fast for 6 hours prior to the experiment to establish a baseline.

- Gavage Solution: Prepare a solution of unlabeled D-glucose (4 g/kg body weight) combined with radiolabeled [¹⁴C(U)]-D-glucose (e.g., 370 Bq/μl). Include a non-absorbable marker like [³H]-Mannitol to correct for adherent extracellular fluid and passive diffusion.

- Administration and Tissue Collection: Administer the solution via feeding tube. After 15 minutes, anesthetize the animal and collect blood from the retro-orbital plexus. Subsequently, euthanize the animal, excise and evert the entire small intestine, and wash thoroughly in ice-cold Krebs buffer.

- Quantification: Divide the small intestine into defined 1-cm segments. Measure the incorporated ¹⁴C radioactivity in each segment and in plasma samples using a liquid scintillation counter. Calculate glucose retention as nmol per cm of tissue. Higher tracer retention in GLUT2-deficient mice compared to wild-types indicates impaired basolateral efflux [13].

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Radiolabeled Glucose Uptake

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying GLUT2 Function

| Reagent / Tool | Function/Application | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Phloretin | Inhibitor of facilitative glucose transporters (GLUTs) [9] | Competitively binds to GLUTs, blocking glucose transport. Used to specifically inhibit GLUT2-mediated basolateral efflux. |

| GLUT2 Knockout Mice | In vivo model for studying systemic glucose homeostasis [13] [4] | Genetically engineered deletion of the Slc2a2 gene to study the phenotypic consequences of a total lack of GLUT2. |

| Radiolabeled [¹⁴C]-D-Glucose | Tracer for quantifying glucose uptake and distribution in vivo [13] [14] | Allows precise measurement of glucose movement through tissues and compartments via radioactivity detection. |

| Anti-GLUT2 Antibodies | Immunodetection (Western Blot, Immunohistochemistry) [13] | Specifically binds to GLUT2 protein for quantifying expression levels and determining its subcellular localization (basolateral vs. apical). |

| Caco-2/TC7 Cell Line | Human intestinal epithelial cell model for in vitro studies [7] | Differentiates into enterocyte-like cells, forming polarized monolayers with defined apical and basolateral membranes to study transporter function and regulation. |

Regulatory Context and Drug Development

Understanding the basolateral role of GLUT2 is crucial for interpreting the mechanisms and limitations of SGLT inhibitors. Pharmacologic strategies have focused almost exclusively on inhibiting the apical sodium-glucose cotransporters (SGLT1 and SGLT2). SGLT2 inhibitors (gliflozins) successfully treat type 2 diabetes by blocking renal glucose reabsorption, promoting glycosuria, and reducing plasma glucose levels [11].

Notably, there are no clinically approved drugs that target intestinal GLUT2. Inhibiting basolateral GLUT2 would be countertherapeutic, as it would trap glucose within the enterocyte, potentially disrupting cellular metabolism and failing to lower systemic blood glucose effectively. Computational models suggest that reducing basolateral GLUT2 activity can indeed decrease net transcellular glucose absorption, primarily by limiting efflux capacity [15]. Therefore, the current therapeutic paradigm affirms the critical conduit function of basolateral GLUT2 by strategically targeting the transport steps that precede it.

The absorption of dietary glucose in the small intestine is a critical process for maintaining systemic energy homeostasis. For decades, the classic paradigm described a two-step mechanism where glucose entered the enterocyte through the apical sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1) and exited via the facilitative glucose transporter 2 (GLUT2) located in the basolateral membrane [16] [9]. This model effectively explained glucose absorption at low luminal concentrations (≤ 10 mM) but failed to account for the massive absorption capacity observed at high luminal glucose concentrations (≥ 25 mM) that far exceed SGLT1's transport capacity [16].

To resolve this discrepancy, the Apical GLUT2 Hypothesis was proposed, suggesting that GLUT2 can be rapidly recruited from intracellular vesicles to the apical membrane in response to high luminal glucose, providing a high-capacity pathway for glucose uptake via facilitated diffusion [16] [9]. This hypothesis has generated significant debate within the scientific community, with supporting and challenging evidence shaping our current understanding of intestinal glucose handling. This whitepaper examines the mechanistic basis, experimental evidence, and ongoing controversies surrounding this hypothesis within the broader context of SGLT1 and GLUT2 function in intestinal glucose absorption research.

Competing Theories of High-Capacity Glucose Absorption

Several theories have emerged to explain the phenomenon of high-capacity glucose absorption that cannot be accounted for by SGLT1 alone.

The Paracellular "Solvent Drag" Theory

Proposed by Pappenheimer, this theory suggests that high luminal glucose concentrations trigger contraction of the peri-junctional actinomyosin ring, dilating intercellular tight junctions and allowing glucose to enter the paracellular space via solvent drag [16] [9].

The Apical GLUT2 Translocation Theory

This theory posits that high luminal glucose activates protein kinase C βII (PKCβII), triggering rapid translocation of pre-formed cytoplasmic GLUT2 vesicles to the apical membrane, creating a high-capacity, facilitative diffusion pathway for glucose entry [16].

Table 1: Comparison of Proposed Mechanisms for High-Capacity Glucose Absorption

| Mechanism | Key Mediators | Glucose Concentration | Kinetic Properties | Proposed Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT1 (Classic) | SGLT1, Na+/K+ ATPase | Low (≤10 mM) | High-affinity, low-capacity, active transport | Apical membrane |

| Basolateral GLUT2 | GLUT2 | All concentrations | Low-affinity, high-capacity, facilitated diffusion | Basolateral membrane |

| Paracellular Transport | Tight junctions | High (≥30 mM) | Non-saturable, passive | Paracellular space |

| Apical GLUT2 (Hypothesis) | GLUT2, PKCβII, cytoskeleton | High (≥30 mM) | Low-affinity, very high-capacity, facilitated diffusion | Apical membrane (inducible) |

Molecular Mechanisms of Proposed GLUT2 Translocation

The apical GLUT2 hypothesis involves a coordinated signaling and trafficking mechanism that responds to high luminal glucose concentrations.

Initiation and Signaling Cascade

The process begins when SGLT1-mediated glucose transport reaches saturation, typically at luminal concentrations exceeding 20-30 mM. Intracellular glucose accumulation or sensing mechanisms subsequently activate protein kinase C βII (PKCβII) [16]. Experimental evidence shows that PKC inhibitors like calphostin C and chelerythrine block the enhanced glucose uptake at high concentrations, while PKC activators like phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) enhance glucose uptake by approximately 20% [16].

Cytoskeletal Involvement and Vesicle Trafficking

The translocation of GLUT2-containing cytoplasmic vesicles to the apical membrane requires an intact cytoskeleton. Studies demonstrate that microtubule disruption with nocodazole and actin filament disruption with cytochalasin B effectively inhibit the increased glucose uptake observed at high glucose concentrations, indicating that both microtubule and actin networks facilitate GLUT2 trafficking to the apical membrane [16].

Diagram 1: Proposed GLUT2 translocation signaling pathway. The mechanism initiates with SGLT1 saturation and progresses through PKC activation and cytoskeletal rearrangement to ultimately insert GLUT2 into the apical membrane.

Critical Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

Supporting Evidence from Cell Line Studies

Research using intestinal cell lines has provided compelling evidence for the apical GLUT2 hypothesis. A comprehensive study utilizing Caco-2, RIE-1, and IEC-6 cell lines demonstrated that glucose uptake saturated at ≥10 mM glucose with brief exposure (≤1 minute), but after ≥5 minutes exposure in Caco-2 and RIE-1 cells, glucose uptake no longer saturated and both Km and Vmax increased significantly [16]. This enhanced uptake was inhibited by phloretin (GLUT2 inhibitor) but not phlorizin (SGLT1 inhibitor), suggesting the involvement of a facilitative glucose transporter distinct from SGLT1 [16].

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of Inhibitors on Glucose Uptake in Intestinal Cell Lines

| Treatment | Target | Effect on Glucose Uptake | Cell Lines Affected | Proposed Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phlorizin | SGLT1 | Inhibition at all glucose concentrations | Caco-2, RIE-1, IEC-6 | Blocks active glucose transport |

| Phloretin | GLUT2 | Inhibition specifically at high glucose (≥20 mM) | Caco-2, RIE-1 | Blocks facilitative glucose transport |

| Nocodazole | Microtubules | Inhibits enhanced uptake at high glucose | Caco-2, RIE-1 | Disrupts vesicular trafficking |

| Cytochalasin B | Actin filaments | Inhibits enhanced uptake at high glucose | Caco-2, RIE-1 | Disrupts cytoskeletal support |

| Calphostin C | PKC | Inhibits enhanced uptake at high glucose | Caco-2, RIE-1 | Blocks PKC signaling pathway |

| Chelerythrine | PKC | Inhibits enhanced uptake at high glucose | Caco-2, RIE-1 | Blocks PKC signaling pathway |

Experimental Protocols for Studying GLUT2 Translocation

Glucose Uptake Assay in Polarized Cell Monolayers

Purpose: To measure time-dependent and concentration-dependent glucose uptake and distinguish between SGLT1 and GLUT2-mediated components [16].

Methodology:

- Culture Caco-2 cells on 24-well plates until fully differentiated and polarized (15 days post-confluence)

- Incubate cell monolayers in 200 μL Krebs buffer with varying glucose concentrations (0.5-50 mM)

- Include 0.5-1 μCi/mL of 14C-D-glucose and 3H-L-glucose simultaneously to measure total and passive uptake, respectively

- Stop uptake by washing twice with ice-cold PBS

- Solubilize cells with 0.1N NaOH at 37°C for 30 minutes

- Measure radioactivity and protein content for normalization

Key Parameters:

- Carrier-mediated (stereospecific) uptake = Total uptake (14C-D-glucose) - Passive uptake (3H-L-glucose)

- Short exposures (≤1 minute) measure constitutive transport

- Extended exposures (≥5 minutes) measure inducible transport components

Inhibitor Studies to Distinguish Transport Mechanisms

Purpose: To pharmacologically dissect the contributions of different transport systems to total glucose uptake [16].

Methodology:

- Pre-treat polarized cell monolayers with specific inhibitors for 15-30 minutes:

- Phlorizin (100-500 μM) to inhibit SGLT1

- Phloretin (100-500 μM) to inhibit GLUT2

- Cytoskeletal disruptors: Nocodazole (10-50 μM) or Cytochalasin B (10-50 μM)

- PKC inhibitors: Calphostin C (1-5 μM) or Chelerythrine (1-5 μM)

- Perform glucose uptake assays as described above

- Compare uptake in presence vs. absence of inhibitors

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for inhibitor studies. This approach allows pharmacological dissection of transport mechanisms by targeting specific components.

Contradictory Evidence from Genetic Models

Despite supportive evidence from cell lines, studies in genetically modified mice have challenged the physiological relevance of apical GLUT2 translocation. Research comparing SGLT1-knockout and GLUT2-knockout mice demonstrated that deletion of SGLT1 drastically reduced glucose retention throughout the entire small intestine, even at high glucose loads (40% glucose solution, 4 g/kg body weight) [17] [14]. Conversely, GLUT2-deficient animals exhibited higher tracer glucose contents in intestinal tissues than wild-type animals [14]. Furthermore, Western blot analysis of apical membrane fractions showed that GLUT2 detection primarily resulted from contamination with basolateral membranes and did not change in density after glucose administration [14]. These findings suggest that SGLT1 remains the primary intestinal glucose transporter even at high luminal concentrations, with GLUT2 playing a basolateral role.

Research Reagent Solutions for Intestinal Glucose Transport Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Intestinal Glucose Transport Mechanisms

| Reagent | Molecular Target | Application/Function | Key Experimental Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phlorizin | SGLT1 (competitive inhibitor) | Discriminates SGLT1-mediated transport | Inhibits active glucose transport; used to isolate facilitative component |

| Phloretin | GLUT2 (inhibitor) | Discriminates GLUT2-mediated transport | Blocks facilitative diffusion; confirms GLUT2 involvement |

| Nocodazole | Microtubules | Disrupts vesicular trafficking | Tests GLUT2 translocation dependence on microtubules |

| Cytochalasin B | Actin filaments | Disrupts cytoskeletal organization | Tests GLUT2 translocation dependence on actin cytoskeleton |

| Calphostin C | PKC (inhibitor) | Blocks protein kinase C signaling | Tests PKC involvement in GLUT2 translocation signaling |

| Chelerythrine | PKC (inhibitor) | Blocks protein kinase C signaling | Confirms PKC role in translocation cascade |

| Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) | PKC (activator) | Activates protein kinase C | Tests if PKC activation mimics high-glucose effects |

| 14C-D-glucose | N/A (tracer) | Measures total glucose uptake | Quantifies carrier-mediated + passive glucose uptake |

| 3H-L-glucose | N/A (tracer) | Measures passive diffusion | Controls for paracellular/passive glucose uptake |

Implications for Drug Development and Therapeutic Applications

The debate surrounding the apical GLUT2 hypothesis has significant implications for pharmaceutical research, particularly in developing treatments for metabolic disorders. While SGLT2 inhibitors have emerged as successful therapies for type 2 diabetes by promoting renal glucose excretion [18] [19], targeting intestinal glucose absorption represents an alternative approach for managing hyperglycemia. If apical GLUT2 significantly contributes to glucose absorption, especially at high carbohydrate loads, it could represent a valuable target for reducing postprandial hyperglycemia. However, the conflicting evidence regarding its physiological relevance has led to prioritization of SGLT1 inhibition for intestinal targeting [9] [18].

Recent research indicates that SGLT1 accounts for the majority of dietary glucose uptake in the intestine, with dual SGLT1/2 inhibitors and specific SGLT1 inhibitors showing promise for diabetes treatment by reducing intestinal glucose absorption while minimizing gastrointestinal side effects [18]. The recognition that SGLT1 mediates glucose-induced incretin secretion [17] [14] further complicates the therapeutic landscape, as inhibiting this transporter may affect multiple aspects of glucose homeostasis.

The Apical GLUT2 Hypothesis represents a compelling mechanism for explaining high-capacity intestinal glucose absorption, supported by substantial in vitro evidence demonstrating GLUT2 translocation to the apical membrane in response to high glucose concentrations. The proposed mechanism involving PKC activation and cytoskeletal rearrangement provides a molecular framework for this phenomenon. However, contradictory evidence from genetic mouse models questions the physiological significance of this pathway in vivo, suggesting SGLT1 remains the dominant transporter even at high luminal glucose concentrations.

Future research should focus on resolving these discrepancies through improved experimental models that better preserve in vivo physiology, development of more specific GLUT2 inhibitors and detection methods, and human studies examining transporter localization under physiological and pathological conditions. Understanding the potential role of apical GLUT2 in disease states, such as diabetes and obesity, where glucose absorption may be altered, remains particularly important. Regardless of the outcome, research stimulated by this hypothesis has significantly advanced our understanding of intestinal glucose handling and continues to inform therapeutic development for metabolic diseases.

The absorption of dietary glucose from the intestinal lumen into the systemic circulation is a fundamental physiological process critical for energy homeostasis. This transcellular journey involves precisely coordinated transport across multiple cellular membranes, primarily mediated by two specialized transporter proteins: sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1) and facilitative glucose transporter 2 (GLUT2). SGLT1, located in the apical membrane of enterocytes, mediates the active uptake of glucose against its concentration gradient, while GLUT2, predominantly found in the basolateral membrane, facilitates the passive efflux of glucose into the blood circulation [20] [21]. Understanding the mechanistic details of this coordinated transport system is essential for research into metabolic diseases and the development of novel therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating glucose absorption.

The significance of these transporters is highlighted by genetic evidence. Humans with mutations in the SGLT1 gene exhibit glucose-galactose malabsorption, a potentially fatal condition if these sugars are not removed from the diet, unequivocally demonstrating SGLT1's indispensable role in apical glucose uptake [20] [21]. Similarly, studies in knockout mouse models have shown that while the absence of SGLT1 drastically reduces intestinal glucose absorption, the deletion of GLUT2 does not completely abolish this process, suggesting a more complex or compensatory role for basolateral efflux [14]. This review synthesizes current research on the coordinated functions of SGLT1 and GLUT2, providing a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals working in this field.

Molecular Mechanisms of Coordinated Transcellular Transport

Apical Entry via SGLT1

SGLT1 (SLC5A1) is a member of the sodium-glucose cotransporter family and is abundantly expressed in the brush border membrane of enterocytes, particularly in the jejunum and ileum [20] [21]. Its transport mechanism is secondary active, coupling the uphill transport of glucose to the downhill transport of sodium ions. Specifically, SGLT1 transports one glucose molecule together with two sodium ions into the cell, utilizing the electrochemical sodium gradient established and maintained by the Na+/K+-ATPase pump located in the basolateral membrane [20] [21]. This stoichiometry (2 Na+:1 glucose) makes the transport process electrogenic and highly efficient.

The kinetic properties of SGLT1 are characterized by a high affinity for its substrates but a relatively low capacity. It has a Michaelis constant (Kt) for D-glucose in the range of 1-7 mM, making it particularly effective at absorbing glucose from low luminal concentrations [20] [21]. SGLT1 exhibits distinct substrate specificity, with a preference for D-glucose > D-galactose > D-methylglucoside > D-3-O-methylglucose, while it does not transport L-glucose or fructose [20]. The transporter can be competitively and potently inhibited by phlorizin, a natural product originally isolated from apple tree bark, which has become an essential pharmacological tool for studying SGLT1 function [6] [22].

Basolateral Exit via GLUT2

Following its entry into the enterocyte, glucose exits across the basolateral membrane into the blood circulation primarily via GLUT2 (SLC2A2), a facilitative diffusion transporter [20] [21]. In contrast to SGLT1, GLUT2 operates without direct energy input, allowing glucose to move down its concentration gradient from the intracellular environment to the serosal side. GLUT2 is a high-capacity, low-affinity transporter with a Km for glucose of approximately 17-40 mM, making it well-suited to handle the high intracellular glucose concentrations that can occur after a meal [20] [21].

GLUT2 has a broader substrate specificity than SGLT1, transporting D-glucose, D-galactose, and D-fructose [21]. Its transport activity is inhibited by phloretin (the aglycone of phlorizin) and cytochalasin B, but not by phlorizin itself, providing a pharmacological profile distinct from SGLT1 [21]. Under normal physiological conditions with low luminal glucose, GLUT2 is predominantly localized to the basolateral membrane of enterocytes. However, evidence suggests that at high luminal glucose concentrations, GLUT2 may be rapidly recruited to the apical membrane, potentially providing an additional high-capacity uptake pathway, though this mechanism remains a subject of ongoing investigation and debate [14] [21].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Intestinal Glucose Transporters

| Characteristic | SGLT1 | GLUT2 |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Family | SLC5A | SLC2A |

| Transport Mechanism | Secondary active (Na+-coupled) | Facilitated diffusion |

| Membrane Localization | Apical (Brush Border) | Primarily Basolateral (can be apical at high glucose) |

| Stoichiometry | 2 Na+ : 1 Glucose | Not applicable |

| Glucose Affinity (Km) | 1-7 mM (High affinity) | 17-40 mM (Low affinity) |

| Driving Force | Na+ electrochemical gradient | Concentration gradient |

| Specific Inhibitors | Phlorizin | Phloretin, Cytochalasin B |

| Substrate Specificity | D-glucose, D-galactose | D-glucose, D-galactose, D-fructose |

Visualization of the Coordinated Transport Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the coordinated transcellular transport of glucose from the intestinal lumen to the blood circulation, highlighting the sequential roles of SGLT1 and GLUT2 and their regulation.

Diagram 1: Coordinated transcellular glucose transport in enterocytes. SGLT1 mediates active apical glucose uptake, while GLUT2 facilitates basolateral efflux. Dotted elements represent potential GLUT2 apical recruitment at high luminal glucose concentrations. The Na+/K+ ATPase maintains the sodium gradient driving SGLT1 activity.

Regulatory Mechanisms of Glucose Transport

Dietary and Nutritional Regulation

The expression and activity of intestinal glucose transporters are dynamically regulated by nutritional status. Fasting and feeding cycles significantly impact glucose absorption capacity. Research using Ussing chamber techniques has demonstrated that glucose-induced currents (indicative of SGLT1 activity) are robustly increased in the jejunum of mice fasted for 24-48 hours compared to ad libitum-fed mice [23]. This suggests an adaptive upregulation of glucose absorptive capacity during fasting, potentially to maximize absorption when nutrients become available. Western blot analyses confirmed that the expression of SGLT1 in brush border membranes was significantly decreased in the jejunum under fed conditions compared to 48-hour fasting [23].

Dietary carbohydrate content also plays a crucial regulatory role. When mice were fed a 60% high glucose diet for three days, the increase in glucose-induced current was observed only in the ileum and was completely suppressed in the jejunum, indicating segment-specific adaptive responses to dietary glucose loads [23]. Furthermore, luminal glucose concentration directly influences transporter activity and localization. At low luminal glucose concentrations (<30 mM), transcellular glucose absorption occurs primarily via SGLT1 in the apical membrane and GLUT2 in the basolateral membrane [20]. At high luminal glucose concentrations (>30 mM), additional mechanisms may be recruited, including the potential insertion of GLUT2 into the apical membrane and increased paracellular permeability, providing a high-capacity absorption pathway [6] [20] [21].

Hormonal and Pharmacological Modulation

Hormonal factors significantly influence the expression and function of intestinal glucose transporters. Dexamethasone, a corticosteroid, has been shown to dose-dependently increase glucose transport in differentiated human Caco-2/TC7 intestinal cell monolayers by upregulating SGLT1 mRNA expression [24]. This effect may contribute to the hyperglycemia associated with long-term corticosteroid use. In animal studies, dexamethasone similarly elevated SGLT1 expression in ileal enterocytes, supporting its role in enhancing intestinal glucose uptake [24].

Incretin hormones are also intimately connected to glucose transporter function. SGLT1 appears to play a crucial role in glucose-sensing mechanisms that trigger the secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) from enteroendocrine cells [14] [21]. Studies in SGLT1-deficient mice have shown abolished GIP and GLP-1 secretion in response to glucose, highlighting the transporter's role beyond nutrient absorption [14].

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of Experimental Interventions on Glucose Absorption

| Experimental Intervention | Model System | Effect on Glucose Absorption | Molecular Target/Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phlorizin (Luminal) | Isolated perfused rat intestine [6] | ~60% reduction at 100 mM luminal glucose | SGLT1 inhibition |

| Phloretin (Vascular) | Isolated perfused rat intestine [6] | ~70-80% reduction at 100 mM luminal glucose | GLUT2 inhibition |

| Combined SGLT1/GLUT2 Blockade | Isolated perfused rat intestine [6] | ~30% absorption remains | Reveals paracellular component |

| Dexamethasone Treatment | Human Caco-2/TC7 cells [24] | Increased glucose transport | SGLT1 mRNA upregulation |

| 24-48 Hour Fasting | Mouse small intestine [23] | Increased glucose-induced current in jejunum | SGLT1 upregulation in BBM |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Isolated Vascularly Perfused Intestine Model

The isolated vascularly perfused rat intestine preparation represents a sophisticated experimental model that preserves the polarity of epithelial cells, the entire transport pathway, and ensures adequate vascular perfusion of the mucosa [6]. This model has proven particularly valuable for studying the relationship between glucose absorption and endocrine secretion.

A typical experimental protocol involves cannulating the superior mesenteric artery and portal vein to establish a closed vascular perfusion system, while the intestinal lumen is separately perfused with test solutions [6]. Glucose absorption is quantified by adding radioactive tracers such as 14C-D-glucose to the luminal perfusate and measuring their appearance in the vascular effluent, allowing for sensitive and accurate quantification. To differentiate between transcellular and paracellular absorption pathways, 14C-D-mannitol is often used as a non-absorbable paracellular marker [6].

Specific transporter activities can be dissected using pharmacological inhibitors: SGLT1 is blocked by luminal administration of phlorizin (typically at 1 μM, which is approximately 250-fold higher than its IC50), while GLUT2 is inhibited by vascular administration of phloretin (typically 1 mM) [6]. This approach has demonstrated that after combined luminal SGLT1 and GLUT2 blockade, approximately 30% of glucose absorption remains, suggesting a significant paracellular transport component, particularly in the proximal small intestine [6].

Ussing Chamber Technique for Electrophysiological Measurements

The Ussing chamber technique provides a powerful method for measuring electrogenic ion and nutrient transport across isolated intestinal epithelia under short-circuit conditions [23]. The preparation involves excising segments of the small intestine, stripping away the muscle layers, and mounting the mucosa-submucosa preparation between two halves of the chamber, effectively separating the mucosal (luminal) and serosal (blood) sides.

The system measures the short-circuit current (Isc), which represents the net active ion transport across the epithelium. The addition of glucose to the mucosal side induces an increase in Isc, reflecting SGLT1-mediated electrogenic Na+-glucose cotransport [23]. This glucose-induced Isc serves as a quantitative measure of SGLT1 activity. Additionally, transepithelial conductance (Gt) can be determined by applying voltage pulses and measuring resulting current changes according to Ohm's law, providing information about epithelial tight junction permeability [23].

This technique has revealed important segmental differences in glucose transport regulation. For instance, in ad libitum-fed mice, glucose-induced Isc is observed in the ileum but is minimal in the jejunum, whereas after 24-48 hours of fasting, robust glucose-induced Isc becomes apparent in both segments [23]. Furthermore, the Ussing chamber allows for the measurement of dilution potentials to assess cation selectivity and paracellular permeability, which has been shown to increase in the jejunum of fasted mice [23].

In Vivo Tracer Studies and Genetically Modified Models

In vivo approaches provide complementary insights into glucose absorption under physiologically relevant conditions. A common method involves oral gavage of radiolabeled glucose (e.g., 14C-D-glucose) to conscious mice, followed by measurement of tracer appearance in blood and retention in intestinal tissues at specific time points [14]. This technique allows for the assessment of the overall efficiency of glucose absorption and its distribution along the intestinal tract.

The use of genetically modified mouse models has been instrumental in defining the specific roles of individual transporters. Studies in SGLT1 knockout mice have demonstrated drastically reduced intestinal glucose retention and abolished incretin secretion following an oral glucose load, unequivocally establishing SGLT1 as the primary intestinal glucose transporter [14]. Interestingly, GLUT2-deficient mice exhibit higher glucose tracer contents in intestinal tissues than wild-type animals, suggesting compensatory mechanisms or altered glucose metabolism [14].

To control for extracellular fluid contamination, non-absorbable markers such as 3H-mannitol are often co-administered with the radioactive glucose tracer [14]. This approach allows researchers to differentiate between truly absorbed glucose and that which merely remains in the intestinal lumen or adherent mucosal fluid.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for studying intestinal glucose transport. The flowchart outlines primary model systems and key measurements for investigating coordinated glucose absorption, from experimental selection to data interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Intestinal Glucose Transport

| Reagent/Material | Specific Example | Function/Application | Key Experimental Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT1 Inhibitor | Phlorizin | Competitive SGLT1 blocker; natural product from apple tree bark | Dissecting SGLT1 contribution to apical uptake (typically 1 μM luminal) [6] [22] |

| GLUT2 Inhibitor | Phloretin | GLUT2 blocker; phlorizin aglycone | Assessing GLUT2 role in basolateral efflux (typically 1 mM vascular) [6] [21] |

| Radioactive Tracers | 14C-D-glucose, 3H-mannitol | Labeled glucose analog and non-absorbable marker | Quantifying glucose absorption and paracellular flux [6] [14] |

| Non-metabolizable Glucose Analogs | α-Methyl-D-glucopyranoside (AMG), 2-Deoxy-D-glucose | Transported but not metabolized | Isolating transport from metabolic effects [23] |

| Differentiated Cell Models | Caco-2/TC7 human intestinal cells | Polarized monolayer with enterocyte-like phenotype | In vitro transport studies, regulation experiments [24] |

| Genetically Modified Mice | SGLT1 knockout, GLUT2 knockout | Lack specific glucose transporters | Defining essential transporter functions in vivo [14] |

| Hormone Assays | GLP-1 ELISA, GIP ELISA | Quantify incretin hormone secretion | Assessing enterendocrine function linked to transport [14] |

Research Implications and Future Directions

The coordinated transcellular transport of glucose via SGLT1 and GLUT2 represents a sophisticated biological system that has important implications for metabolic disease management. The evidence clearly establishes SGLT1 as the primary apical glucose transporter essential for glucose absorption and incretin secretion, while GLUT2 serves as the principal basolateral efflux pathway [14] [21]. However, important questions remain regarding the regulation of GLUT2 membrane trafficking and its potential apical recruitment under high glucose conditions.

Pharmacological inhibition of SGLT1 has emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy for managing hyperglycemia in metabolic diseases. Recent developments in SGLT1 inhibitors have shown potential for reducing postprandial blood glucose levels without serious gastrointestinal side effects [20]. The finding that approximately 30% of glucose absorption persists after combined SGLT1 and GLUT2 blockade suggests a significant paracellular component, particularly in the proximal intestine, which may represent an additional regulatory point [6].

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the precise molecular signals that regulate the membrane trafficking of glucose transporters in response to dietary status, the potential crosstalk between transcellular and paracellular absorption pathways, and the development of more specific transporter inhibitors with optimal therapeutic profiles. A comprehensive understanding of these coordinated transport mechanisms will continue to inform the development of novel interventions for diabetes, obesity, and related metabolic disorders.

Expression Patterns and Localization Along the Intestinal Tract

The absorption of dietary glucose is a critical process for maintaining systemic energy homeostasis, and it is primarily mediated by two key transporter proteins: the sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1, SLC5A1) and the facilitative glucose transporter 2 (GLUT2, SLC2A2) [25] [1]. Within the context of intestinal glucose absorption research, understanding the precise expression patterns and localization of these transporters along the intestinal tract is fundamental. Their distribution is not uniform and is subject to complex regulatory mechanisms that respond to dietary composition, luminal glucose concentrations, and metabolic demands [25] [21]. This in-depth technical guide synthesizes current research to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed overview of the expression topography, quantitative data, and experimental methodologies essential for investigating SGLT1 and GLUT2 in the intestine.

Transporter Physiology and Core Functions

SGLT1 (SLC5A1)

SGLT1 is a high-affinity, low-capacity secondary active transporter. It couples the transport of one glucose (or galactose) molecule with two sodium ions, utilizing the inwardly directed sodium gradient generated by the Na+/K+-ATPase as its driving force [25] [1]. Its high affinity for glucose is evidenced by an apparent Km value of 0.5 mM [25] [26]. SGLT1-mediated uptake is specifically inhibited by phlorizin [25].

GLUT2 (SLC2A2)

GLUT2 is a low-affinity, high-capacity facilitative diffusion system that allows glucose to move down its concentration gradient [4] [25]. It transports D-glucose, D-galactose, and fructose with apparent Km values of approximately 17 mM, 92 mM, and 76 mM, respectively [25]. GLUT2-mediated transport is inhibited by phloretin and cytochalasin B, but not by phlorizin [25].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of SGLT1 and GLUT2

| Feature | SGLT1 | GLUT2 |

|---|---|---|

| Gene | SLC5A1 | SLC2A2 |

| Transport Mechanism | Secondary active (Na+-coupled) | Facilitated diffusion |

| Stoichiometry | 2 Na+ : 1 Glucose | N/A |

| Primary Kinetics (Km Glucose) | High-affinity (0.5 mM) | Low-affinity (~17 mM) |

| Inhibitors | Phlorizin | Phloretin, Cytochalasin B |

| Sugar Specificity | D-glucose, D-galactose | D-glucose, D-galactose, Fructose |

Expression Patterns and Regional Localization

The expression of SGLT1 and GLUT2 varies significantly along the length of the gastrointestinal tract, reflecting specialized functional roles in different regions.

SGLT1 Expression Topography

SGLT1 is predominantly expressed in the small intestine. Proteomic analyses have identified it as one of the most abundantly expressed plasma membrane proteins in the mouse small intestine [25]. Its expression is highest in the duodenum and jejunum and decreases toward the ileum [25] [1]. Only minor mRNA expression is detected in the colon [25]. At the cellular level, SGLT1 protein is primarily localized to the brush border membrane (BBM) of mature enterocytes lining the villi, with weak or no staining detected in the crypt cells [25] [21]. SGLT1 is also present in enteroendocrine cells, specifically K-cells that secrete glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and L-cells that secrete glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) [25] [26].

GLUT2 Expression Topography

GLUT2 is also highly expressed throughout the small intestine [25]. In mice, similar abundances of Glut2 mRNA are observed in the jejunum, ileum, and colon [25]. Its membrane localization is dynamic and dependent on luminal glucose concentrations. Under fasting or low luminal glucose conditions, GLUT2 is predominantly located in the basolateral membrane (BLM) of enterocytes [25] [21]. However, the presence of high luminal glucose can trigger the rapid recruitment of GLUT2 to the brush border membrane [25] [21]. This dual localization model is a key concept in understanding high-capacity glucose absorption.

Table 2: Localization of SGLT1 and GLUT2 in the Intestinal Tract

| Intestinal Segment | SGLT1 Expression & Localization | GLUT2 Expression & Localization |

|---|---|---|

| Duodenum | High expression in BBM [25] [1] | High mRNA in rat > mouse >> human; dynamic BBM/BLM localization [25] |

| Jejunum | High expression and transport capacity in BBM [25] | High expression; dynamic BBM/BLM localization [25] |

| Ileum | Lower expression compared to proximal intestine [25] | High expression in mice; dynamic BBM/BLM localization [25] |

| Colon | Minor mRNA expression [25] | mRNA expression detected in mice [25] |

| Enteroendocrine Cells | Present in K- and L-cells [25] | Information not specified in search results |

Experimental Protocols for Localization and Functional Analysis

Protocol 1: Assessing Transporter Abundance via Brush Border Membrane (BBM) Isolation and Western Blotting

This protocol is used to isolate the BBM fraction and quantify transporter protein levels, often in response to dietary or experimental challenges [13] [14].

- Tissue Harvesting: Sacrifice animals and rapidly dissect the desired intestinal segments.

- Mucosa Scraping: Open the intestine longitudinally, rinse with ice-cold buffer (e.g., Krebs buffer), and scrape off the mucosal layer.

- Homogenization: Homogenize the scraped mucosa in an ice-cold hypotonic buffer (e.g., 100 mM mannitol, 2 mM HEPES/Tris, pH 7.4) containing protease inhibitors and PMSF.

- MgCl2 Precipitation: Add MgCl2 to the homogenate to a final concentration of 20 mM to precipitate non-brush border membranes. Incubate on ice for 15 minutes.

- Differential Centrifugation:

- Centrifuge at low speed (3,000×g for 15 minutes) to pellet the precipitated material.

- Collect the supernatant, which is enriched in BBM vesicles, and centrifuge at a high speed (e.g., 30,000×g for 30 minutes) to pellet the BBM.

- Protein Quantification and Western Blotting: Resuspend the final BBM pellet. Determine protein concentration. Perform SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using validated antibodies against SGLT1 and GLUT2. A critical step is to probe for a basolateral marker protein (e.g., Na+/K+-ATPase) to assess and control for cross-contamination of the BBM fraction [13].

Protocol 2: In Vivo Functional Uptake Assay Using Radiolabeled Glucose

This protocol measures the functional absorption and tissue retention of glucose in different intestinal segments [13] [14].

- Animal Preparation: Fast animals for a standardized period (e.g., 6 hours) to establish a baseline.

- Glucose Gavage: Administer a defined glucose bolus (e.g., 4 g/kg body weight) via oral gavage. The solution should contain a radiolabeled glucose tracer (e.g., [14C(U)]-D-glucose). To correct for adherent luminal fluid, a non-absorbable marker like [3H]-D-mannitol can be included.

- Tissue Collection: After a set period (e.g., 15 minutes), sacrifice the animals. Quickly remove the entire small intestine and evert it. Wash thoroughly with ice-cold buffer to remove luminal contents.

- Segmenting and Processing: Divide the intestine into defined segments (e.g., 1 cm pieces) and digest the tissues or extract the radiolabel.

- Quantification: Measure the retained radioactivity in each tissue segment and in plasma samples using a liquid scintillation counter. Calculate the glucose retention per unit length of intestine (e.g., nmol/cm/15 min).

Visualization of Glucose Absorption and Regulatory Pathways

Intestinal Glucose Absorption and Sensing Pathway

This diagram illustrates the coordinated roles of SGLT1 and GLUT2 in enterocytes for glucose absorption and in enteroendocrine cells for incretin secretion.

Experimental Workflow for Transporter Localization Study

This diagram outlines a standard experimental workflow for investigating transporter localization and function, integrating the protocols described above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Models for Investigating Intestinal Glucose Transporters

| Reagent / Model | Function / Application | Key Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Inhibitors | Pharmacological blockade to assess transporter-specific function. | Phlorizin: Potent, selective SGLT1 inhibitor [13] [1].Phloretin: Inhibits GLUT2-mediated transport [25]. |

| Antibodies | Detection and localization of transporters via Western Blot (WB) and Immunohistochemistry (IHC). | Validate specificity for target transporter (SGLT1/GLUT2). Critical for confirming purity of BBM fractions using basolateral markers (e.g., Na+/K+-ATPase) [13]. |

| Genetically Modified Mouse Models | Study the non-redundant, essential role of each transporter in vivo. | SGLT1 KO: Requires glucose/galactose-free diet to survive; used to study glucose absorption and incretin secretion [13] [14].GLUT2 KO: Used to study systemic glucose homeostasis; requires GLUT1 re-expression in pancreatic β-cells to survive [13] [14]. |

| Radiolabeled Tracers | Quantitative measurement of functional glucose uptake and absorption. | [14C]-D-Glucose: Tracks glucose disposition [13] [14].[3H]-D-Mannitol: Non-absorbable volume marker for correction [13] [14]. |

| Cell Lines | In vitro model for studying transporter regulation and function. | Differentiated Caco-2 cells: A model for human enterocytes, expressing SGLT1 and GLUT2 [25]. |

The expression and dynamic localization of SGLT1 and GLUT2 along the intestinal tract are precisely regulated to ensure efficient glucose absorption. SGLT1 serves as the primary, high-affinity apical entry point, particularly in the duodenum and jejunum, and is indispensable for glucose sensing in enteroendocrine cells. GLUT2, with its high capacity and dual localization in the BBM and BLM, provides a adaptable pathway for glucose efflux and bulk absorption. The experimental methodologies and reagents detailed in this guide provide a foundation for ongoing research aimed at understanding these processes in health and disease. Targeting the regulatory pathways of these transporters continues to hold significant promise for therapeutic interventions in metabolic disorders such as diabetes and obesity.

Research Tools and Therapeutic Translation: From Knockout Models to Drug Discovery

The utilization of genetically modified mouse models has been instrumental in elucidating the distinct and complementary roles of the sodium-glucose cotransporter SGLT1 and the facilitative glucose transporter GLUT2 in intestinal glucose absorption. Studies employing SGLT1 knockout (Sglt1⁻/⁻) and intestinal epithelial cell-specific GLUT2 knockout (GLUT2ΔIEC) mice have demonstrated that SGLT1 is the primary mediator of apical glucose uptake under both low and high luminal glucose concentrations, and is essential for glucose-induced incretin secretion. In contrast, GLUT2 appears dispensable for apical glucose influx but significantly influences basolateral glucose exit and whole-body glucose homeostasis. This whitepaper synthesizes key phenotypic findings from these genetic models, provides detailed methodological protocols for critical experiments, and discusses the implications for drug development targeting intestinal glucose handling in metabolic diseases.

Intestinal glucose absorption is a critical process for maintaining systemic energy balance, with dysregulation contributing to metabolic disorders like type 2 diabetes and obesity. For decades, the absorption mechanism was conceptualized through a two-transporter system: SGLT1 mediating active, sodium-coupled glucose uptake across the apical brush-border membrane, and GLUT2 facilitating passive glucose efflux across the basolateral membrane into the circulation [17] [13]. However, this model was challenged by hypotheses suggesting GLUT2 could be recruited to the apical membrane during high carbohydrate loads to contribute to bulk absorption via facilitated diffusion.

The generation and characterization of SGLT1 and GLUT2 knockout mice have provided definitive insights to resolve these controversies. This whitepaper consolidates findings from these genetic models, framing them within the broader context of intestinal glucose transporter research. It aims to serve as a technical resource for researchers and drug development professionals by summarizing quantitative phenotypic data, detailing essential experimental protocols, and visualizing core concepts and workflows.

Phenotypic Characterization of Knockout Models

The physiological roles of SGLT1 and GLUT2 have been clarified through the comparative study of respective knockout mouse models, which reveal distinct and critical functions for each transporter.

SGLT1 Knockout (Sglt1⁻/⁻) Mice

- Viability and Diet Dependency: Sglt1⁻/⁻ mice develop a lethal glucose-galactose malabsorption (GGM) syndrome when fed a standard diet but thrive and are healthy when maintained on a glucose- and galactose-free diet [27]. This underscores the non-redundant, essential role of SGLT1 for absorbing dietary glucose and galactose.

- Intestinal Glucose Absorption: Sglt1⁻/⁻ mice exhibit a drastically reduced intestinal absorption of radiolabeled glucose following an oral gavage, with tracer retention decreased throughout the entire small intestine compared to wild-type mice [17] [13]. This establishes SGLT1 as the primary pathway for glucose transport across the brush-border membrane, independent of the glucose load.

- Incretin Secretion: Glucose-triggered secretion of the incretin hormones GIP and GLP-1 is abolished in Sglt1⁻/⁻ mice [27] [17] [13]. Immunohistochemistry confirms SGLT1 localization in GIP- and GLP-1-positive cells, identifying it as a key intestinal glucose sensor.

- Renal Glucose Handling: Micropuncture studies indicate SGLT1 reabsorbs approximately 3% of filtered glucose under normoglycemic conditions, defining its minor but significant contribution to renal glucose reabsorption [27].

GLUT2 Knockout (GLUT2ΔIEC) Mice

- Intestinal Glucose Absorption: Unlike SGLT1 deletion, intestinal-specific inactivation of GLUT2 results in moderate glucose malabsorption and a delayed distribution of oral sugar to peripheral tissues [28]. GLUT2-deficient animals can even exhibit higher intestinal tracer glucose contents than wild-types, potentially due to impaired basolateral exit and subsequent intracellular accumulation [17] [13].

- Metabolic Phenotype: GLUT2ΔIEC mice display limited weight gain despite normal food intake, improved glucose tolerance, and increased ketone body production, mimicking a state of calorie restriction [28].

- Incretin Secretion: GLUT2 deletion does not impair glucose-induced GIP or GLP-1 secretion [17] [13], but it does modulate L-cell function, reducing GLP-1 positive cell density while increasing GLP-1 content per cell [28].

- Systemic Adaptations: These mice show secondary adaptations including reduced microvillus length, altered gut microbiota composition, and improved systemic inflammatory status [28].

Table 1: Quantitative Physiological Data from SGLT1 and GLUT2 Knockout Mouse Models

| Phenotypic Parameter | SGLT1 Knockout (Sglt1⁻/⁻) | GLUT2 Knockout (GLUT2ΔIEC) | Experimental Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-Gavage Plasma Glucose | Severely reduced elevation [17] [13] | Delayed tissue distribution [28] | Oral gavage of 4 g/kg D-glucose |

| Intestinal Glucose Uptake | Drastically reduced (~5-10% of WT) [17] [13] | Unchanged or increased [17] [13] | ¹⁴C-D-glucose tracer, 15 min post-gavage |

| GIP Secretion | Abolished [27] [17] [13] | Unimpaired [17] [13] | Measured 15 min post-glucose gavage |

| GLP-1 Secretion | Abolished [27] [17] [13] | Unimpaired [17] [13] | Measured 15 min post-glucose gavage |

| Renal Glucose Reabsorption | ~3% of filtered load [27] | Not specifically reported | Micropuncture in normoglycemia |

| Body Weight & Metabolism | Normal on special diet [27] | Limited weight gain, improved glucose tolerance [28] | Long-term observation on standard chow |

Table 2: Summary of Knockout Model Conclusions

| Aspect | SGLT1 Conclusion | GLUT2 Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Transport Role | Pivotal for apical uptake at all concentrations [27] [17] [13] | Critical for basolateral exit; minimal apical role [17] [13] |

| Role in Incretin Secretion | Essential glucose sensor for GIP and GLP-1 secretion [27] [17] [13] | Not required for glucose-induced secretion [17] [13] |

| Therapeutic Implication | High-potential target for slowing glucose absorption [27] | Target for inducing mild malabsorption/metabolic improvement [28] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a technical toolkit, this section outlines key methodologies used to characterize the knockout models.

Oral Glucose Gavage and Tracer Uptake

This protocol is fundamental for assessing in vivo intestinal glucose absorption capacity [17] [13] [14].

- Animal Preparation: Mice are fasted for 6 hours (or overnight, 16-18 hours) with free access to water. Sglt1⁻/⁻ mice must be pre-fed a glucose-galactose-free diet for at least one week prior.

- Gavage Solution: A 40% (w/v) D-glucose solution is prepared in PBS. For tracer studies, the solution is supplemented with 370 Bq/µL of [¹⁴C(U)]-D-glucose and 370 Bq/µL of [¹³H(N)]-D-Mannitol (to correct for adherent fluid). A standard bolus is 4 g glucose per kg body weight.

- Procedure: The solution is administered via a feeding tube. After 15 minutes, blood is collected from the retro-orbital plexus or tail vein under anesthesia for plasma glucose, hormone, and tracer analysis. Mice are then euthanized by cervical dislocation.

- Tissue Processing: The entire small intestine is quickly removed, everted, and thoroughly washed in ice-cold Krebs buffer. It is divided into sequential 1-cm segments. The radioactivity in each segment is measured using a liquid scintillation counter. Glucose retention is calculated as nmol of glucose per cm of intestine over 15 minutes.

Brush Border Membrane Vesicle (BBMV) Preparation and Uptake

This ex vivo method isolates the apical membrane to study transporter function and density directly [27] [13].

- BBMV Isolation: Mice are euthanized, and the small intestinal mucosa is scraped off and homogenized in a mannitol-HEPES buffer (e.g., 100 mM mannitol, 2 mM HEPES/Tris, pH 7.1). MgCl₂ is added to a final concentration of 10-20 mM to precipitate non-apical membranes. The homogenate is kept on ice for 15-20 min and then centrifuged at low speed (3,000 × g, 15 min). The supernatant is centrifuged at high speed (27,000 × g, 30 min). The resulting pellet, enriched in BBMVs, is resuspended in a vesicle buffer and snap-frozen.

- Uptake Assay: Thawed BBMVs are incubated at 22°C with a buffer containing 100 mM NaSCN or KSCN and 0.1 mM [¹⁴C]AMG (a non-metabolizable SGLT1 substrate). Uptake is measured with and without 0.2 mM phlorizin (an SGLT1 inhibitor). The reaction is stopped with ice-cold stop solution containing phlorizin. Vesicles are collected on nitrocellulose filters via rapid filtration and washed, and retained radioactivity is quantified.

Hormone and Metabolite Analysis

- Blood Collection for Hormones: Blood is collected into EDTA-coated tubes containing a dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV) inhibitor to prevent incretin degradation [27] [17]. Plasma is separated by centrifugation.

- ELISA Measurements: Plasma concentrations of active GLP-1, total GIP, and insulin are determined using commercial ultra-sensitive ELISA kits (e.g., from Millipore Corporation and ALPCO Diagnostics) according to manufacturer protocols [27] [28] [17].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for characterizing glucose absorption and incretin secretion in knockout mouse models, showing divergent phenotypic outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Investigating Intestinal Glucose Transport

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SGLT1 Knockout Mice | Model for SGLT1 deficiency; requires glucose-free diet [27] | Sglt1⁻/⁻ on 129/OLA/C57BL/6 background |

| GLUT2 Knockout Mice | Model for global GLUT2 deficiency [17] | Lethal; requires β-cell rescue (RIPGLUT1) |

| Inducible GLUT2ΔIEC Mice | Model for intestinal-specific GLUT2 deletion [28] | Slc2a2FLOX/FLOX × Villin-CreERT2; tamoxifen-induced |

| Phlorizin | Potent, specific SGLT1 inhibitor [17] [13] | Used in BBMV uptake assays (0.2 mM) |

| Phloretin | GLUT2 inhibitor [29] | Used to probe GLUT2 function |

| ³H-/¹⁴C-labeled D-Glucose | Tracer for in vivo/in vitro glucose flux studies [17] [13] | Corrected for fluid phase with ³H-mannitol |

| ¹⁴C-α-Methyl-D-Glucoside (AMG) | Non-metabolizable SGLT1 substrate [27] | Ideal for BBMV uptake assays |

| Anti-SGLT1 Antibody | Immunodetection and localization of SGLT1 [27] | Custom or commercial (e.g., Chemicon) |

| Anti-GLUT2 Antibody | Immunodetection and localization of GLUT2 [28] | Custom or commercial |

| GLP-1 & GIP ELISA Kits | Quantification of plasma incretin levels [27] [28] [17] | Kits from Millipore, MesoScale Discovery |

| DPP-IV Inhibitor | Stabilizes active incretin hormones in blood samples [27] [17] | Added immediately to blood collection tubes |

Signaling, Transport Pathways, and Regulatory Mechanisms

The data from knockout models support a refined model of intestinal glucose handling. SGLT1 is unequivocally the primary and indispensable apical glucose transporter. Its function is not merely to absorb low concentrations of glucose but is also pivotal for mass absorption at high luminal loads [27] [17] [13]. Furthermore, SGLT1 is located in enteroendocrine cells and is essential for triggering glucose-induced secretion of GIP and GLP-1, acting as a key glucose sensor [27] [17].