Insulin, Glucagon, and Beyond: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Innovations in Blood Glucose Regulation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the hormonal regulation of blood glucose, synthesizing foundational physiology with cutting-edge research and therapeutic applications.

Insulin, Glucagon, and Beyond: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Innovations in Blood Glucose Regulation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the hormonal regulation of blood glucose, synthesizing foundational physiology with cutting-edge research and therapeutic applications. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the intricate balance between insulin and glucagon, delving into molecular signaling pathways, secretory mechanisms, and the emerging role of α-cell plasticity. It further evaluates state-of-the-art methodological approaches for hormone and biomarker analysis, examines pathophysiological disruptions in diabetes, and critically assesses current and emerging therapeutic strategies, including dual and triple agonists. The review aims to bridge foundational knowledge with translational innovation, offering a roadmap for future diabetes and metabolic disease research.

The Core Duet: Foundational Physiology of Insulin and Glucagon in Glucose Homeostasis

The pancreatic islets of Langerhans represent a complex endocrine micro-organ essential for systemic metabolic homeostasis, primarily through the regulated secretion of glucagon and insulin [1] [2]. These two counter-regulatory hormones are produced in close proximity by alpha (α) and beta (β) cells, respectively, enabling a sophisticated feedback system that maintains blood glucose concentrations within a narrow physiological range [3] [1]. Disruption of this delicate equilibrium is a hallmark of diabetes mellitus, a group of metabolic diseases affecting hundreds of millions worldwide [2]. While traditional pathophysiological models of diabetes have predominantly focused on insulin deficiency and resistance, emerging research underscores the critical role of alpha cell dysfunction and inappropriate glucagon secretion in disease pathogenesis [4] [5]. This whitepaper synthesizes current knowledge of the cellular origins, secretory triggers, and functional interplay between pancreatic alpha and beta cells, providing a technical foundation for researchers and drug development professionals working within the framework of hormonal blood glucose regulation.

Cellular Origins and Islet Architecture

The pancreatic islets contain multiple endocrine cell types strategically organized to facilitate metabolic regulation [2]. Beta cells, which produce insulin, constitute the majority (approximately 60-80%) of the islet cell population and are predominantly located at the core of human islets [2]. Alpha cells, which produce glucagon, account for approximately 30-40% of the islet population and typically form a mantle surrounding the beta cell core in rodent islets, though this architecture shows species-specific variations [1] [2]. Other endocrine cell types include delta (δ) cells that produce somatostatin, epsilon (ε) cells that produce ghrelin, and PP cells that produce pancreatic polypeptide, each playing modulatory roles in islet function [2].

This spatial arrangement is crucial for the paracrine interactions that fine-tune hormone secretion [1] [2]. The close proximity allows secretory products from one cell type to directly influence the function of neighboring cells, creating a robust regulatory network that enables precise response to metabolic demands [1].

Beta Cell Function: Insulin Synthesis and Secretion

Insulin Structure and Biosynthesis

Insulin is synthesized as preproinsulin and processed to proinsulin through cleavage of the signal peptide [6]. Proinsulin is then converted to insulin and C-peptide via proteolytic cleavage and stored in secretory granules awaiting release [6]. The crystal structure of insulin reveals a complex organization where the active monomer consists of a 21-amino acid A-chain and a 30-amino acid B-chain linked by two disulfide bonds [6]. Insulin stored in β-cells is packed into densely clustered granules as insoluble crystalline hexamers coordinated with zinc atoms, reaching concentrations of approximately 40 mM [6]. The hexamer serves as the storage form, while the monomer is the active form that dissociates upon secretion into the bloodstream [6].

Table 1: Key Structural Features of Insulin

| Structural Component | Characteristics | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Structure | 51 amino acids; A-chain (21 aa) and B-chain (30 aa) | Determines receptor binding affinity |

| Disulfide Linkages | Two interchain (A7-B7, A20-B19); one intrachain (A7-A11) | Stabilizes tertiary structure |

| Storage Form | Zinc-coordinated hexamer (≈40 mM concentration in granules) | Stable packaging within secretory granules |

| Active Form | Monomer (dissociates upon secretion) | Binds insulin receptor |

| Critical Binding Regions | N-terminus of A-chain, C-terminus of both chains | Mutation causes reduced receptor affinity (e.g., insulin Wakayama, Chicago) |

Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion (GSIS)

Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion involves a sequence of events in β-cells that lead to fusion of secretory granules with the plasma membrane [6]. The process occurs through two complementary pathways: the triggering pathway and the metabolic amplifying pathway [1] [2].

The triggering pathway begins with glucose uptake into β-cells through glucose transporters (GLUT1 and GLUT3 in humans; GLUT2 in rodents) [1] [2]. Following uptake, glucose is phosphorylated by glucokinase, which serves as the rate-limiting step for glucose entry into the glycolytic pathway [2]. Subsequent glucose metabolism through glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle generates ATP, increasing the ATP/ADP ratio [1] [2]. This elevated ATP/ADP ratio causes closure of ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels, leading to membrane depolarization [2]. Subsequently, voltage-gated calcium channels open, allowing influx of extracellular Ca2+ [1] [2]. The resulting sharp increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) triggers the exocytosis of insulin secretory granules [1] [2].

The metabolic amplifying pathway operates in parallel to enhance insulin secretion independently of further KATP channel activity, primarily through mechanisms that facilitate the recruitment and priming of insulin granules for release [2]. Mitochondria play a crucial role in this process by serving as metabolic and redox centers, establishing connections with plasma membrane channels, insulin granule vesicles, and cellular redox balance [2]. Additionally, metabolic signals such as NADPH production contribute to the amplification of insulin secretion [2].

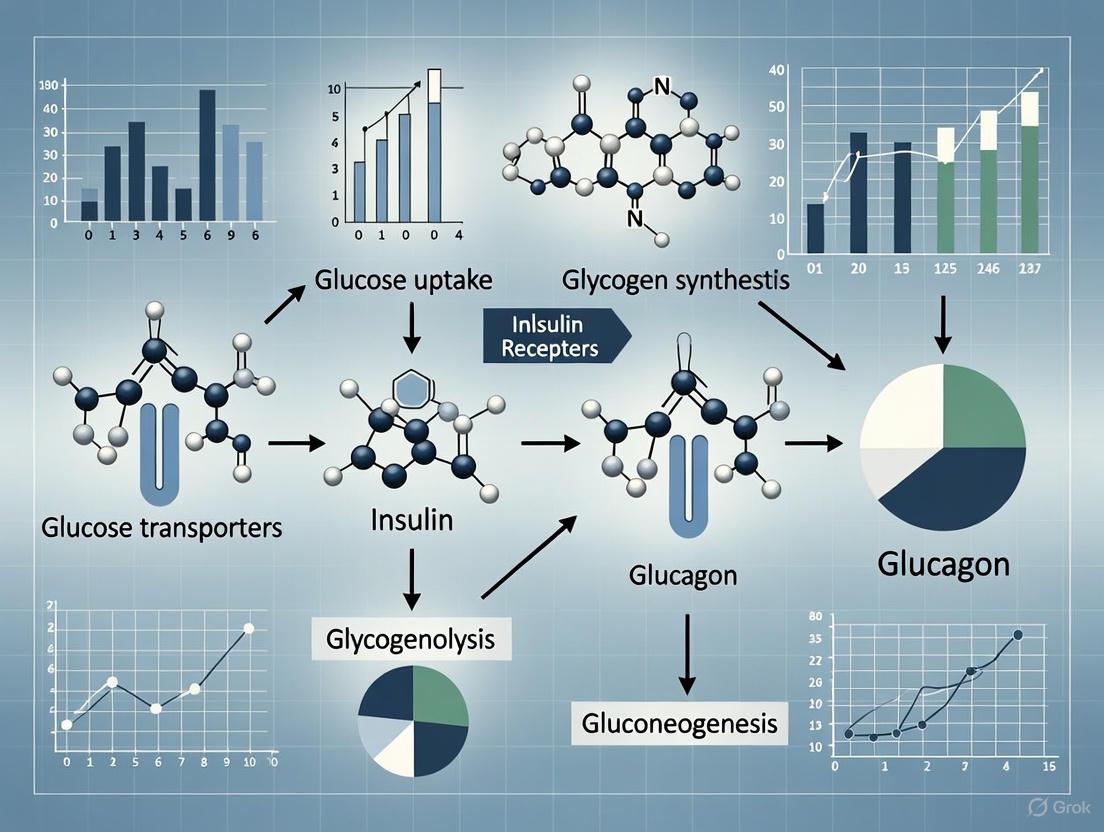

Diagram 1: Beta Cell Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion Pathway. This diagram illustrates the key steps in the triggering pathway of GSIS, from glucose uptake to calcium-triggered exocytosis of insulin granules.

Additional Regulators of Insulin Secretion

Beyond glucose, various nutrients, hormones, and neural inputs modulate insulin secretion. Free fatty acids and amino acids can augment glucose-induced insulin secretion [6]. Hormonal regulators include melatonin, estrogen, leptin, growth hormone, and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) [6]. The cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA)/exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (EPAC) system serves as a critical signaling hub for many hormonal modulators [1] [6]. When activated by stimuli such as GLP-1 or glucagon receptor engagement, cAMP signaling potentiates GSIS without triggering insulin secretion independently [1].

Recent research has identified additional regulatory mechanisms that constrain insulin secretion to prevent excessive release. The nutrient sensor mTORC1 is rapidly activated by glucose in β-cells and acts as an intrinsic feedback regulator that restrains insulin secretion via RhoA-dependent actin remodeling, limiting vesicle movement and dampening the second phase of insulin secretion [7].

Alpha Cell Function: Glucagon Synthesis and Secretion

Glucagon Biosynthesis and Structure

Glucagon is a 29-amino acid peptide hormone derived from the preproglucagon gene (GCG) [1]. In pancreatic alpha cells, proglucagon is processed by prohormone convertase 2 (PC2), resulting in the generation of glucagon and the major proglucagon fragment [1]. This processing differs from that in intestinal L cells, where prohormone convertase PC1/3 generates GLP-1 and other products from the same precursor [1]. The crystal structure of glucagon was solved in the 1950s, following its identification as a pancreatic hormone that elevates blood glucose levels [5].

Regulation of Glucagon Secretion

Glucagon secretion is tightly regulated by nutrients, endocrine factors, and neural inputs [5]. The primary stimulus for glucagon release is low blood glucose concentration, which directly affects alpha cell electrical activity [5]. During hypoglycemia, reduced glucose metabolism decreases the ATP/ADP ratio, promoting the opening of KATP channels and membrane hyperpolarization, which ultimately triggers action potentials and calcium influx that stimulate glucagon exocytosis [5].

Table 2: Primary Regulators of Glucagon Secretion

| Regulatory Factor | Effect on Secretion | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Hypoglycemia | Stimulates | ↓ ATP/ADP ratio; KATP channel opening; Ca2+ influx |

| Amino Acids | Stimulates | Direct nutrient signaling; cAMP elevation |

| Somatostatin | Inhibits | SSTR2 activation; ↓ cAMP & Ca2+ levels |

| Insulin | Inhibits | PI3K-Akt pathway; inhibition of exocytosis |

| GABA | Inhibits | GABAA receptor activation; membrane hyperpolarization |

| Zn2+ | Inhibits | KATP channel modulation; membrane hyperpolarization |

| Sympathetic Nervous System | Stimulates | β-adrenergic receptor activation; ↑ cAMP |

| GLP-1 | Inhibits | GLP-1 receptor signaling; paracrine/neural pathways |

| GIP | Stimulates | GIP receptor activation; cAMP signaling |

Intracellular cAMP signaling serves as the primary trigger for glucagon secretion, with calcium acting as a secondary messenger [5]. During stress or fasting, sympathetic activation increases cAMP levels, triggering glucagon release through PKA and EPAC activation, which enhances calcium channel activity and vesicle trafficking [5]. Additional GPCR pathways, including Gq-coupled receptors such as the vasopressin 1b receptor (V1bR), activate phospholipase C (PLC) and generate inositol trisphosphate (IP3), leading to increased intracellular calcium and enhanced glucagon release [5].

Paracrine inhibition from neighboring islet cells represents a crucial regulatory layer. Insulin, somatostatin, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and zinc (co-secreted with insulin) all suppress glucagon secretion through distinct mechanisms [5]. Insulin activates its receptor on alpha cells, inhibiting exocytosis through PI3K-Akt-dependent pathways [5]. Somatostatin binds to somatostatin receptor subtype 2 (SSTR2), reducing cAMP and calcium levels [5]. GABA activates GABAA receptors, leading to chloride influx and membrane hyperpolarization, while zinc influences KATP channels to promote hyperpolarization [5]. Disruption of these inhibitory pathways in type 2 diabetes contributes to paradoxical hyperglucagonemia and impaired glycemic control [5].

Diagram 2: Alpha Cell Glucagon Secretion Regulation. This diagram illustrates the complex regulation of glucagon secretion, highlighting cAMP as the primary intracellular trigger and the modulatory role of paracrine inhibition from other islet cells.

Paracrine and Endocrine Crosstalk in Islet Function

Alpha to Beta Cell Communication

Alpha cells significantly influence beta cell function through paracrine signaling. The most well-established paracrine factor is glucagon itself, which binds to glucagon receptors on beta cells and activates the cAMP/PKA/EPAC system, thereby potentiating GSIS [1]. This stimulatory effect was first documented in 1965 and has since been confirmed in multiple model systems [1]. Isolated beta cells exhibit reduced cAMP content and impaired GSIS, both of which are restored by the presence of alpha cells or exogenous glucagon [1]. Interestingly, glucagon can also activate the GLP-1 receptor on beta cells, triggering similar downstream signaling events [1].

Beyond glucagon, alpha cells secrete additional factors that modulate beta cell function. Glutamate, co-released with glucagon, may influence beta cells through NMDA receptors, though its effects appear context-dependent [1]. In humans, alpha cells can produce and release acetylcholine, which functions as a paracrine signal to sensitize beta cells to prevailing glucose concentrations [1]. This acetylcholine activates muscarinic receptors on beta cells, initiating the phospholipase C (PLC)/diacylglycerol (DAG)/protein kinase C (PKC) cascade that enhances GSIS [1].

Beta to Alpha Cell Communication

Beta cells reciprocally regulate alpha cell function through several inhibitory pathways. Insulin itself acts on insulin receptors present on alpha cells to suppress glucagon secretion through PI3K-Akt-dependent pathways [5]. Zinc, co-packaged with insulin in secretory granules and co-secreted upon glucose stimulation, promotes alpha cell hyperpolarization by modulating KATP channels [5]. GABA, synthesized from glutamate by the enzyme glutamic acid decarboxylase in beta cells, activates GABAA receptors on alpha cells, leading to chloride influx and membrane hyperpolarization that inhibits glucagon release [1] [5]. These multifaceted inhibitory mechanisms ensure appropriate suppression of glucagon secretion during hyperglycemia.

Emerging Concepts: Intra-islet GLP-1 and Oxytocin

Recent research has revealed that pancreatic alpha cells can produce and release glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) under certain conditions, creating an intra-islet incretin system [8]. This intra-islet GLP-1 acts locally to potentiate insulin secretion in a glucose-dependent manner [8]. A newly discovered hormonal pathway links oxytocin to this intra-islet GLP-1 system. Oxytocin stimulates GLP-1 release from pancreatic alpha cells, which subsequently enhances insulin secretion, particularly under high glucose conditions [8]. This indirect action—oxytocin triggering alpha cells to release GLP-1, which then acts on beta cells—represents a novel mechanism for controlling insulin release that is glucose-dependent, making it a potentially safe option for regulating blood sugar [8].

Experimental Methodologies for Islet Cell Research

Key Research Models and Approaches

The study of alpha and beta cell function employs a range of sophisticated experimental models and approaches. Isolated pancreatic islets from various species (particularly rodents and humans) serve as a primary ex vivo model for investigating secretory function and paracrine interactions [1]. These islets can be studied in static incubation systems or more dynamic perifusion assays that provide temporal resolution of hormone secretion [9]. Isolated islets can be further dissociated into individual cells for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to obtain purified populations of alpha and beta cells [1].

Genetic mouse models with tissue-specific ablation or overexpression of key genes involved in hormone secretion have been instrumental in delineating signaling pathways in vivo [1] [9]. For instance, mice with beta cell-specific ablation of the GLP-1 receptor revealed that the physiological effects of GLP-1 may involve non-endocrine mechanisms, possibly neuronal relay systems between the intestine and endocrine pancreas [9].

Advanced imaging techniques, including live-cell imaging of intracellular calcium dynamics and vesicle trafficking, provide real-time visualization of stimulus-secretion coupling events [1]. These approaches can be complemented by electrophysiological methods such as patch clamping to characterize ion channel activity and membrane potential changes in response to secretagogues [2].

Assessment of Hormone Secretion and Cell Function

Table 3: Key Methodologies for Assessing Alpha and Beta Cell Function

| Methodology | Application | Key Measured Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Islet Perifusion | Dynamic hormone secretion | Temporal pattern of insulin/glucagon release; pulsatility |

| Static Insulin/Glucagon Secretion Assay | Batch sampling of hormone output | Total hormone secreted under defined conditions |

| Patch Clamp Electrophysiology | Ion channel function | KATP channel activity; membrane potential; Ca2+ currents |

| Live-cell Calcium Imaging | Intracellular Ca2+ dynamics | [Ca2+]i oscillations; response to secretagogues |

| Immunofluorescence Microscopy | Islet architecture; hormone co-localization | Cellular composition; receptor distribution |

| cAMP FRET Sensors | Real-time cAMP dynamics | Spatiotemporal cAMP signaling in live cells |

| Single-cell RNA sequencing | Transcriptomic profiling | Cell-type specific gene expression; heterogeneity |

For quantitative assessment of hormone secretion, radioimmunoassays (RIA) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) remain standard techniques for measuring insulin and glucagon concentrations in experimental samples and clinical specimens [5]. These assays can be applied to both in vitro systems and in vivo during metabolic tests such as the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) [9].

To investigate intracellular signaling pathways, researchers employ phosphoproteomic profiling to identify phosphorylation changes in proteins involved in processes such as actin remodeling and vesicle trafficking [7]. This approach revealed that mTORC1 modulates the phosphorylation of proteins in the RhoA-GTPase pathway, providing mechanistic insight into how this nutrient sensor constrains insulin exocytosis [7].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Islet Cell Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Hormone Receptor Agonists | Exendin-4 (GLP-1R); Glucagon | Receptor activation; cAMP signaling studies |

| Hormone Receptor Antagonists | Exendin(9-39) (GLP-1R) | Receptor blockade; pathway dissection |

| Ion Channel Modulators | Diazoxide (KATP opener); Tolbutamide (KATP closer) | Electrophysiology; GSIS mechanism studies |

| Metabolic Inhibitors | 2-deoxyglucose; Oligomycin | Metabolic pathway dissection |

| Signaling Pathway Inhibitors | Rapamycin (mTORC1); H-89 (PKA) | Specific pathway inhibition; mechanism studies |

| Cell Isolation Enzymes | Collagenase P; Liberase | Islet isolation for ex vivo studies |

| Fluorescent Indicators | Fura-2 (Ca2+); cAMP FRET sensors | Live-cell imaging of second messengers |

Pathophysiological Implications and Therapeutic Perspectives

Dysregulation of alpha and beta cell function is central to diabetes pathogenesis. In type 1 diabetes, autoimmune destruction of beta cells leads to absolute insulin deficiency, while also eliminating the paracrine inhibition of alpha cells, resulting in inappropriate glucagon secretion that exacerbates hyperglycemia [3] [5]. In type 2 diabetes, progressive beta cell dysfunction occurs alongside peripheral insulin resistance, while alpha cells develop resistance to the suppressive effects of insulin and glucose, leading to fasting and postprandial hyperglucagonemia [3] [5].

Therapeutic strategies increasingly target both alpha and beta cell dysfunction. GLP-1 receptor agonists enhance glucose-dependent insulin secretion while suppressing glucagon release, addressing both hormonal defects [10]. Emerging approaches include dual and triple agonists that target multiple related receptors (GLP-1R, GIPR, GCGR) to achieve superior metabolic outcomes [10]. Glucagon receptor antagonists have shown efficacy in lowering blood glucose in diabetic patients, supporting the "glucagonocentric hypothesis" of diabetes [5]. Additionally, research into alpha-to-beta cell conversion offers potential regenerative approaches for restoring functional beta cell mass [4].

The intricate partnership between alpha and beta cells exemplifies the sophistication of metabolic regulation. Continued research into their cellular origins, secretory triggers, and functional interplay will undoubtedly yield novel therapeutic insights for diabetes and related metabolic disorders.

This technical guide provides a comprehensive analysis of the molecular mechanisms underlying insulin and glucagon receptor signaling and their integrated regulation of metabolic homeostasis. We examine the intricate signaling cascades, downstream metabolic effects, and experimental approaches used to investigate these pathways. With the growing therapeutic importance of multi-agonist drugs targeting incretin receptors, this review synthesizes current understanding of receptor crosstalk, pathway integration, and metabolic outcomes relevant to conditions including obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. The content is structured to serve researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working in metabolic disease therapeutics.

The maintenance of systemic glucose homeostasis is primarily governed by the counter-regulatory hormones insulin and glucagon, which orchestrate complex molecular interactions across multiple tissues. These hormones activate specific receptor-mediated signaling pathways that coordinate anabolic and catabolic processes to ensure metabolic stability. Recent research has revealed substantial complexity in these signaling systems, including pathway crosstalk, feedback mechanisms, and opportunities for therapeutic intervention through multi-receptor targeting [11] [10]. The development of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and emerging multi-agonists represents a paradigm shift in metabolic disease treatment, leveraging our growing understanding of these interconnected pathways [10] [12]. This review examines the molecular architecture of insulin and glucagon signaling systems, their integration in metabolic regulation, and the experimental approaches driving discovery in this field.

Insulin Signaling: Molecular Architecture and Metabolic Regulation

Insulin Receptor Activation and Downstream Cascades

Insulin signaling initiates with hormone binding to the transmembrane insulin receptor (IR), triggering receptor autophosphorylation and activation of its intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity. This activation recruits and phosphorylates insulin receptor substrate (IRS) proteins, which serve as docking platforms for downstream signaling components. The primary metabolic pathway involves IRS recruitment of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), which generates phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) at the membrane, facilitating phosphorylation and activation of AKT (protein kinase B) [13].

Activated AKT serves as a central signaling node, translocating to various cellular compartments to regulate multiple metabolic processes including glucose uptake, glycogen synthesis, and lipid metabolism. AKT phosphorylates and inhibits glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), relieving inhibition of glycogen synthase and promoting glycogen storage. Simultaneously, AKT activation stimulates translocation of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) to the plasma membrane through additional downstream effectors, enhancing cellular glucose uptake [13]. The insulin signaling network exhibits emergent properties including bistability, where the activation threshold for AKT phosphorylation differs from its deactivation threshold, creating a hysteretic response that maintains metabolic state stability despite fluctuating glucose levels [14].

Insulin Signaling Disruption in Metabolic Disease

Insulin resistance represents a state of diminished cellular responsiveness to insulin stimulation, characterized by disruptions at multiple points in the signaling cascade. Molecular mechanisms underlying insulin resistance include serine phosphorylation of IRS proteins that inhibits their function, reduced PI3K/AKT pathway activation, and inflammatory signaling through pathways such as JNK and IKKβ that interfere with insulin signal transduction [13]. These disruptions lead to impaired glucose uptake in peripheral tissues, uncontrolled hepatic glucose production, and aberrant lipid metabolism, collectively contributing to the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes and related metabolic disorders.

Table 1: Key Components of Insulin Signaling Pathway and Functional Roles

| Signaling Component | Activation Mechanism | Primary Metabolic Functions | Dysregulation Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin Receptor (IR) | Insulin binding, autophosphorylation | Initial signal transduction | Impaired insulin sensitivity |

| IRS proteins | Tyrosine phosphorylation by IR | Scaffold for signaling complex | Serine phosphorylation inhibits function |

| PI3K | Recruitment to IRS | PIP3 generation | Reduced AKT activation |

| AKT | Phosphorylation by PDK1/2 | GLUT4 translocation, glycogen synthesis | Impaired glucose disposal |

| GSK3β | Inhibition by AKT phosphorylation | Regulation of glycogen synthase | Increased glycogen synthase inhibition |

Glucagon Signaling: Mechanisms and Metabolic Effects

Glucagon Receptor Signaling Cascade

Glucagon exerts its effects through binding to the glucagon receptor (GCGR), a class B G protein-coupled receptor primarily expressed in the liver, with lower expression in kidney, adipose tissue, and other organs [11]. GCGR activation stimulates dissociation of heterotrimeric G proteins into Gαs and Gβγ subunits. Gαs activates adenylate cyclase, increasing intracellular cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels, which in turn activates protein kinase A (PKA) [15]. Additionally, glucagon receptor signaling can activate the IP3-AMPK signaling pathway, providing an alternative mechanism for metabolic regulation [15].

Activated PKA phosphorylates numerous downstream targets including transcription factors, enzymes, and other regulatory proteins. In the liver, PKA-mediated phosphorylation activates key enzymes in gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis while inhibiting glycogen synthase. PKA also phosphorylates cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB), which translocates to the nucleus and activates transcription of gluconeogenic enzymes including phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) and glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase) [11]. Recent evidence indicates that glucagon signaling also regulates amino acid metabolism through a liver-pancreatic alpha cell axis, stimulates lipolysis and mitochondrial fat oxidation, reduces caloric intake, and increases energy expenditure, at least in animal models [11].

Emerging Roles of Glucagon in Metabolic Regulation

Beyond its classical hyperglycemic effects, glucagon signaling has demonstrated importance in broader metabolic processes. Global elimination of glucagon receptor signaling in mice decreases median lifespan by 35% in lean animals and renders mice unresponsive to the metabolic benefits of caloric restriction, including reduced liver fat and improved serum lipids [15]. Glucagon signaling appears indispensable for activation of key nutrient-sensing pathways including AMPK and for appropriate regulation of mTOR activity in response to dietary interventions [15]. These findings position glucagon as a crucial regulator of metabolic health beyond its glucose-elevating effects.

Table 2: Metabolic Processes Regulated by Glucagon Signaling

| Metabolic Process | Mechanism of Regulation | Primary Tissues | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose production | PKA-mediated enzyme phosphorylation | Liver | Hyperglycemic effect limits therapeutic use |

| Lipid metabolism | Stimulation of lipolysis, fat oxidation | Liver, adipose tissue | Potential for treating MASLD/NAFLD |

| Energy expenditure | Unclear; possibly CNS-mediated | CNS, peripheral tissues | Obesity treatment |

| Amino acid metabolism | Liver-pancreatic alpha cell axis | Liver, pancreas | Relationship with gluconeogenesis |

| Longevity pathways | AMPK activation, mTOR inhibition | Multiple | Healthspan extension |

Signaling Pathway Integration and Crosstalk

Insulin-Glucagon Reciprocal Regulation

The insulin and glucagon signaling systems function as an integrated network rather than independent pathways, with multiple points of crosstalk and reciprocal regulation. Insulin not only stimulates glucose uptake and lipid synthesis but also inhibits glucagon secretion from pancreatic alpha cells and antagonizes many catabolic processes activated by glucagon [14]. Conversely, glucagon signaling can modulate insulin sensitivity through effects on substrate competition and direct signaling interference. Computational modeling of this integrated network reveals bistable behavior in the anabolic zone (glucose >5.5 mmol/L), where the positive feedback of AKT on IRS creates hysteresis in the system response [14].

This bistability provides a buffering mechanism that maintains metabolic state stability despite fluctuations in nutrient availability. The modeling further indicates that the positive feedback of calcium on cAMP is responsible for ensuring ultrasensitive response in the catabolic zone (glucose <4.5 mmol/L), while crosstalk between AKT and phosphodiesterase 3 (PDE3) enables efficient catabolic response under low glucose conditions [14]. These emergent properties of the integrated signaling network illustrate how insulin and glucagon cooperatively maintain metabolic homeostasis through complex nonlinear interactions.

Incretin Hormones and Multi-Agonist Therapeutics

The incretin hormones GIP and GLP-1 have emerged as crucial regulators of insulin and glucagon secretion with important therapeutic implications. GLP-1 receptor agonists enhance glucose-dependent insulin secretion, suppress glucagon secretion, delay gastric emptying, and reduce food intake through central appetite suppression [10] [12]. GIP exerts complementary effects, stimulating insulin secretion during hyperglycemia while having glucagonotropic effects during hypoglycemia, and directly promoting lipogenesis in adipose tissue [12].

The development of multi-agonists that simultaneously target multiple receptors represents a significant advancement in metabolic therapeutics. Several GCGR-based multi-agonists (mazdutide, survodutide, retatrutide) have demonstrated substantial efficacy for weight loss in people with obesity while improving liver health in those with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) [11]. These unimolecular compounds typically incorporate moieties that activate both GLP-1 and glucagon receptors, with GLP-1 receptor activation mitigating the hyperglycemic effects of glucagon receptor activation [11]. The success of these agents underscores the therapeutic potential of targeting multiple interconnected hormonal pathways simultaneously.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Computational Analysis of Signaling Networks

Computational approaches provide powerful tools for analyzing the complex behaviors emerging from insulin-glucagon signaling interactions. Mathematical modeling of the integrated network enables simulation of system responses to various perturbations and prediction of behaviors difficult to observe experimentally [14]. A representative modeling approach involves:

Network Construction: Define all molecular species and interactions based on established literature, including receptors, secondary messengers, enzymes, and transcription factors. Key interactions should include insulin-mediated AKT activation, glucagon-mediated PKA activation, and crosstalk mechanisms such as AKT-mediated PDE3 activation and calcium-mediated cAMP modulation [14].

Parameter Estimation: Determine kinetic parameters from experimental data where available, using optimization algorithms to estimate unknown parameters. Validation should include comparison to experimental data such as IRS and AKT activation profiles in adipocytes [14].

System Perturbation: Simulate the network response to varying concentrations of insulin, glucagon, glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids. Analyze steady-state profiles for key signaling nodes (AKT phosphorylation, PKA activation) and defined output indices such as phosphorylation state (Ps) [14].

Bifurcation Analysis: Identify parameter regions exhibiting bistability or other nonlinear behaviors. Determine how feedback loops and crosstalk mechanisms shape these emergent properties [14].

This computational framework has revealed that certain macronutrient compositions may be more conducive to homeostasis than others and identified network perturbations that may contribute to disease states such as diabetes, obesity, and cancer [14].

Genetic and Pharmacological Manipulation

Genetic manipulation approaches provide crucial insights into signaling pathway functions:

Global and Tissue-Specific Knockout Models: Global glucagon receptor knockout (Gcgr KO) mice demonstrate the essential role of glucagon signaling in metabolic responses to caloric restriction [15]. Liver-specific knockout models (Gcgrhep−/−) enable dissection of tissue-specific functions, revealing that hepatic glucagon receptor signaling is necessary for CR-induced changes in AMPK and mTOR activity [15].

Pharmacological Activation: Acute and chronic administration of glucagon analogues (e.g., NNC9204-0043) allows investigation of glucagon receptor signaling effects on downstream pathways including cAMP production, AMPK activation, and mTOR inhibition [15]. Dosing regimens typically involve single injections for acute effects (e.g., 1.5 nmol/kg BW subcutaneous) or prolonged administration for chronic effects.

Metabolic Phenotyping: Comprehensive assessment includes body composition analysis (NMR), indirect calorimetry for energy expenditure and respiratory quotient, oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTT), insulin tolerance tests (ITT), and tissue collection for molecular analysis of signaling pathway activation [15].

Diagram 1: Glucagon receptor signaling pathway and downstream metabolic effects

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Insulin-Glucagon Signaling

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Models | Gcgr KO, Gcgrhep−/−, IRS KO mice | Pathway necessity studies | Determine tissue-specific functions |

| Receptor Agonists | NNC9204-0043, dual/tri-agonists | Pharmacological activation | Pathway-specific effects |

| Antibodies | Phospho-AKT, phospho-PKA, total proteins | Western blot, IHC | Detect pathway activation |

| Metabolic Assays | OGTT, ITT, indirect calorimetry | Physiological assessment | Whole-body metabolic phenotyping |

| cAMP Assays | ELISA, FRET-based biosensors | Second messenger measurement | Quantify GCGR activation |

| Hormone Analytics | GLP-1, GIP, insulin ELISAs | Hormone level quantification | Correlate with signaling states |

Visualization of Integrated Metabolic Signaling

Diagram 2: Integrated insulin and glucagon signaling network with key regulatory nodes

The molecular mechanisms of insulin and glucagon receptor signaling represent a complex, integrated system for maintaining metabolic homeostasis. Understanding these pathways at a detailed level provides crucial insights for developing novel therapeutic approaches for metabolic diseases. The emergence of multi-agonists that simultaneously target multiple receptors highlights the translational importance of this basic research. Continued investigation using the experimental approaches outlined in this review will further elucidate the intricate regulation of these pathways and their potential as therapeutic targets for obesity, diabetes, MASLD, and other cardio-kidney-metabolic conditions.

The precise regulation of blood glucose is a fundamental physiological process, essential for survival and metabolic health. While insulin serves as the primary hypoglycemic hormone, a sophisticated counter-regulatory system exists to antagonize its effects and prevent dangerous drops in blood glucose. This system comprises several hormones—glucagon, adrenaline, cortisol, and growth hormone—that work in concert to maintain glucose homeostasis, particularly during fasting, stress, and exercise [16] [5]. Understanding the dynamics of these hormones is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to address metabolic diseases such as diabetes mellitus.

The "glucagonocentric hypothesis" represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of metabolic regulation, positing that glucagon is not merely insulin's counter-regulatory counterpart but a central driver of metabolic physiology and pathophysiology [5]. This framework is vital for interpreting the complex hormonal interactions that govern systemic energy balance. Disruptions in this delicate equilibrium are hallmarks of diabetes and other metabolic disorders, making the counter-regulatory system a prime target for therapeutic intervention. This review synthesizes current evidence on the mechanisms, interactions, and experimental approaches for studying these critical hormonal regulators.

Core Counter-Regulatory Hormones and Their Mechanisms

The counter-regulatory response involves a coordinated sequence of hormonal actions with distinct temporal characteristics and mechanisms.

Glucagon: The Primary Rapid Responder

Glucagon, a 29-amino-acid peptide secreted by pancreatic α-cells, is the most critical hormone for acute glucose counter-regulation [16] [5]. Its secretion is stimulated by hypoglycemia, protein-rich meals, and sympathetic activation [5]. Glucagon primarily acts on the liver, where it activates hepatic glucose output through two key processes: glycogenolysis (breakdown of glycogen to glucose) and gluconeogenesis (synthesis of glucose from non-carbohydrate precursors) [17] [3] [5]. The onset of glucagon's insulin-antagonistic effect is rapid, making it the first line of defense against falling blood glucose levels [16].

The molecular mechanism of glucagon action involves binding to a specific G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) on hepatocytes, which activates adenylate cyclase to increase intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels [18] [5]. This cascade activates protein kinase A (PKA), which in turn phosphorylates key enzymes that promote glycogen breakdown and gluconeogenic pathways [5]. Recent research has revealed that glucagon's role extends beyond glucose regulation to include modulation of amino acid metabolism, lipid oxidation, and appetite control [5].

Adrenaline: The Secondary Messenger

Adrenaline (epinephrine) is released from the adrenal medulla in response to hypoglycemia and other stress conditions [16]. When glucagon secretion is deficient, as in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes, adrenaline becomes the most important hormone for glucose recovery during hypoglycemia [16]. Adrenaline contributes to glucose elevation through multiple mechanisms: directly stimulating hepatic glucose output, promoting glycogenolysis in muscle, enhancing gluconeogenesis, and inhibiting glucose uptake by peripheral tissues [16].

Adrenaline induces early post-hypoglycemic insulin resistance, which can persist for several hours after glucose normalization [16]. Its effects are mediated through β-adrenergic receptors that activate cAMP-dependent pathways similar to glucagon, as well as α-adrenergic receptors that utilize calcium and inositol phosphate signaling systems [5].

Cortisol and Growth Hormone: Delayed Regulators

Cortisol and growth hormone exhibit counter-regulatory effects that manifest after a lag period of several hours [16]. These hormones are particularly important during prolonged hypoglycemia, where they help sustain glucose levels by inducing insulin resistance in peripheral tissues and promoting alternative fuel utilization [16] [3].

Growth hormone reduces glucose utilization by cells and increases fat mobilization, thereby conserving glucose for glucose-dependent tissues [3]. The pronounced insulin-antagonistic effect of growth hormone suggests it plays a key role in regulating diurnal rhythms of glucose metabolism, including the dawn phenomenon [16]. Cortisol promotes gluconeogenesis, antagonizes insulin action in peripheral tissues, and synergizes with other counter-regulatory hormones to maintain fasting glucose levels [16].

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Counter-Regulatory Hormones

| Hormone | Site of Secretion | Primary Stimulus | Onset of Action | Major Metabolic Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucagon | Pancreatic α-cells | Hypoglycemia, protein meals, sympathetic activation | Rapid (minutes) | ↑ Hepatic glycogenolysis & gluconeogenesis, ↑ amino acid catabolism, ↑ lipid oxidation |

| Adrenaline | Adrenal medulla | Hypoglycemia, stress | Rapid (minutes) | ↑ Hepatic glucose output, ↑ muscle glycogenolysis, ↓ peripheral glucose uptake |

| Cortisol | Adrenal cortex | Prolonged hypoglycemia, stress | Slow (hours) | ↑ Gluconeogenesis, ↑ peripheral insulin resistance, ↑ protein catabolism |

| Growth Hormone | Anterior pituitary | Prolonged hypoglycemia, stress | Slow (hours) | ↑ Peripheral insulin resistance, ↑ lipolysis, ↓ glucose utilization |

Quantitative Hormone Dynamics and Pancreatic Stores

Understanding the quantitative aspects of hormone secretion and pancreatic reserves provides critical insights for metabolic disease research.

Hormonal Dynamics in Glucose Regulation

In healthy individuals, fasting blood glucose concentrations typically range between 80-90 mg/dL, with postprandial levels rising to 120-140 mg/dL before returning to baseline within 2 hours [3]. This stability is maintained through the pulsatile secretion of insulin and precisely timed counter-regulatory responses [18] [3]. During hypoglycemia, glucagon secretion increases dramatically, with adrenaline becoming significant if hypoglycemia persists or when glucagon is deficient [16].

The insulin-antagonistic effects of these hormones occur at different potencies and time courses. Glucagon and adrenaline exert their effects within minutes, while cortisol and growth hormone require several hours to manifest their full impact [16]. The hierarchy of importance varies with context: glucagon is paramount for acute counter-regulation, while adrenaline serves as a critical backup, and cortisol/growth hormone contribute to prolonged responses [16].

Pancreatic Hormone Content in Health and Disease

Post-mortem analyses of pancreatic tissue reveal significant differences in hormone stores between non-diabetic and type 2 diabetic (T2D) subjects. A study of 20 lean non-diabetic, 19 obese non-diabetic, and 18 T2D subjects found that pancreatic insulin content was 35% lower in T2D subjects (7.4 mg versus 11.3 mg in non-diabetic subjects) [19]. In contrast, pancreatic glucagon content was similar between T2D and non-diabetic subjects (0.76 mg versus 0.81 mg) [19]. This disparity resulted in a significantly higher glucagon/insulin ratio in T2D subjects (17.4% versus 11.7% in non-diabetic subjects) [19].

Notably, pancreatic somatostatin content was 29% lower in T2D subjects, though the ratios of somatostatin to both insulin and glucagon were not significantly different [19]. These findings indicate that the secretory abnormalities characteristic of T2D cannot be attributed solely to alterations in pancreatic hormone reserves, suggesting instead functional dysregulation in secretion control [19].

Table 2: Pancreatic Hormone Content in Non-Diabetic and Type 2 Diabetic Subjects

| Parameter | Lean Non-Diabetic (n=20) | Obese Non-Diabetic (n=19) | All Non-Diabetic (n=39) | Type 2 Diabetic (n=18) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin Content (mg) | 10.2 ± 3.7 | 12.5 ± 3.9 | 11.3 ± 3.9 | 7.4 ± 3.9* |

| Glucagon Content (mg) | 0.92 ± 0.49 | 0.70 ± 0.33 | 0.81 ± 0.43 | 0.76 ± 0.45 |

| Somatostatin Content (mg) | 0.036 ± 0.017 | 0.040 ± 0.018 | 0.038 ± 0.017 | 0.027 ± 0.015* |

| Glucagon/Insulin Ratio (%) | 13.5 ± 6.6 | 9.8 ± 4.3 | 11.7 ± 5.8 | 17.4 ± 7.7* |

Note: Data presented as mean ± SD; *P < 0.05 compared to All Non-Diabetic group

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Key Experimental Protocols

Several sophisticated methodologies have been developed to study counter-regulatory hormone dynamics:

Pancreatic Hormone Extraction and Quantification: Human pancreatic tissue obtained at autopsy can be processed for hormone measurement. Tissue samples are homogenized in acid-ethanol solution for hormone extraction, followed by centrifugation and collection of supernatants [19]. Hormone concentrations are determined using specific radioimmunoassays (RIAs) or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) for insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin [19]. Total pancreatic hormone content is calculated by multiplying hormone concentration by pancreas weight, accounting for regional variations in islet distribution (higher density in tail vs. head/body) [19].

Perfused Mouse Pancreas Model: This ex vivo system allows precise control of the pancreatic microenvironment. The pancreas is isolated with intact vascular supply and perfused with oxygenated buffer containing specific nutrient or pharmacologic stimuli [20]. Efficient blockage of glucagon signaling can be achieved using specific glucagon receptor (GCGR) antagonists like des-His¹-Glu⁹-glucagon amide, while GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) blockade utilizes exendin(9-39) [20]. Effluent samples are collected at timed intervals for hormone measurement by RIA to assess dynamic secretion patterns [20].

Intra-islet Paracrine Signaling Studies: To investigate communication between α- and β-cells, researchers employ specific receptor antagonists and genetic models. The impact of glucagon signaling on insulin secretion is studied using GCGR blockers in perfused pancreas systems and isolated islets [20]. Similarly, the effects of insulin on α-cells are examined using insulin receptor antagonists and β-cell-specific insulin receptor knockout models [5]. These approaches have revealed that insulin normally suppresses glucagon secretion through PI3K-Akt-dependent pathways, a mechanism impaired in T2D [5].

Mass Spectrometry for Bioactive GLP-1 Detection: Duke researchers developed a high-specificity mass spectrometry assay to detect only the bioactive form of GLP-1, avoiding interference from inactive fragments that often confound traditional measurements [21]. This methodology revealed that pancreatic α-cells produce substantial bioactive GLP-1, particularly when glucagon production is blocked, demonstrating remarkable α-cell plasticity [21].

Signaling Pathway Visualization

Glucagon and GLP-1 Signaling Pathways

Emerging Concepts and Therapeutic Implications

Alpha Cell Plasticity and GLP-1 Production

Recent research has uncovered remarkable flexibility in pancreatic α-cell function. Duke University studies demonstrate that when glucagon production is blocked by inhibiting the prohormone convertase PC2, α-cells increase production of GLP-1 via the enzyme PC1 [21]. This shift improves glucose control and enhances insulin secretion, suggesting GLP-1 is a more powerful insulin stimulator than glucagon [21]. This plasticity represents a potential endogenous mechanism for maintaining glucose homeostasis that could be therapeutically harnessed.

The discovery that pancreatic α-cells, not just intestinal L-cells, produce significant amounts of bioactive GLP-1 challenges traditional paradigms [21]. Using mass spectrometry, researchers found that human pancreatic tissue produces much higher levels of bioactive GLP-1 than previously believed, with production directly linked to insulin secretion [21]. This finding is particularly relevant for diabetes drug development, as GLP-1 receptor agonists are already established therapies.

Intra-islet Paracrine Communication

The pancreatic islet functions as a micro-organ with sophisticated cell-to-cell communication. Insulin, zinc, GABA, and somatostatin secreted by β- and δ-cells provide paracrine inhibition of glucagon release from α-cells [5]. In type 2 diabetes, resistance to insulin's suppressive effect on α-cells contributes to hyperglucagonemia and impaired glycemic control [5]. Understanding these paracrine interactions is essential for developing therapies that restore normal islet function rather than simply replacing individual hormones.

Research using perfused mouse pancreas models demonstrates that insulin secretion depends on intra-islet glucagon signaling [20]. Blocking glucagon receptors impairs insulin secretion, revealing that the glucagon receptor plays a physiological role in maintaining insulin secretion, likely through the cAMP signaling pathway [20]. This challenges the simplistic view of glucagon solely as an insulin antagonist and highlights the complexity of islet cross-talk.

Glucagon-Centric View of Metabolic Disease

The "glucagonocentric hypothesis" positions glucagon as a central driver of diabetic hyperglycemia, not merely a counter-regulatory hormone [5]. Hyperglucagonemia is present in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes and contributes significantly to fasting and postprandial hyperglycemia [5]. In T1DM, lack of insulin removes its inhibitory effect on α-cells, leading to inappropriate glucagon secretion even during hyperglycemia [5]. In T2DM, α-cells become resistant to insulin-mediated suppression [5].

Glucagon's role extends beyond glycemic control to include regulation of amino acid metabolism, lipid oxidation, bile acid turnover, and thermogenesis [5]. Disruptions in these pathways contribute to the pathogenesis of NAFLD, CKD, and cardiovascular complications, suggesting glucagon dysregulation may be an upstream factor driving diabetic complications across multiple organ systems [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Counter-Regulatory Hormone Studies

| Reagent / Method | Function / Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| GCGR Antagonists (e.g., des-His¹-Glu⁹-glucagon amide) | Competitive blockade of glucagon receptors to study glucagon signaling pathways | Used in perfused pancreas and isolated islet studies to demonstrate intra-islet glucagon dependency for insulin secretion [20] |

| GLP-1R Antagonists (e.g., exendin(9-39)) | Specific inhibition of GLP-1 receptors to delineate GLP-1-mediated effects | Employed to distinguish GLP-1 signaling from glucagon signaling in α-cell studies [20] |

| Mass Spectrometry Assay | High-specificity detection of bioactive GLP-1, excluding inactive fragments | Enabled discovery of substantial GLP-1 production in human pancreatic α-cells [21] |

| Prohormone Convertase Inhibitors (PC1/PC2 blockade) | Selective inhibition of hormone processing enzymes to study α-cell plasticity | Demonstrates α-cell switch from glucagon to GLP-1 production when PC2 is blocked [21] |

| Specific RIAs/ELISAs | Precise quantification of hormone concentrations in tissues and fluids | Used to measure insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin in pancreatic extracts from diabetic and non-diabetic subjects [19] |

| Perfused Pancreas System | Ex vivo model maintaining intact vascular and paracrine signaling | Allows precise control of pancreatic microenvironment and dynamic assessment of hormone secretion [20] |

The counter-regulatory hormone system represents a complex, multi-layered network that maintains glucose homeostasis through precisely coordinated interactions. The traditional view of glucagon as merely insulin's counter-regulatory hormone has evolved to recognize its central role as a master regulator of nutrient metabolism and a significant contributor to the pathophysiology of diabetes and related metabolic disorders. Emerging concepts of α-cell plasticity, intra-islet paracrine communication, and multi-organ glucagon signaling provide new frameworks for understanding metabolic disease.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these advances open promising therapeutic avenues. Targeting α-cell plasticity, restoring normal paracrine signaling within islets, and developing balanced multi-agonist molecules that engage both insulin and glucagon pathways represent frontier areas in metabolic disease therapeutics. As our understanding of counter-regulatory dynamics continues to deepen, so too will opportunities to develop more effective treatments for diabetes and related metabolic disorders that address the root causes of hormonal dysregulation rather than merely compensating for its consequences.

For decades, the prevailing model of hormonal blood glucose regulation placed insulin deficiency and resistance as the central pathophysiologic drivers of diabetes mellitus. Within this framework, glucagon was viewed primarily as insulin's counter-regulatory hormone, tasked with preventing hypoglycemia by stimulating hepatic glucose production [5] [22]. However, recent research has catalyzed a conceptual shift toward the "glucagonocentric hypothesis," which posits that glucagon is not merely a counter-regulatory hormone but a key systemic regulator of energy balance with multifaceted roles beyond glycemic control [5] [22]. This whitepaper synthesizes current evidence demonstrating glucagon's critical involvement in amino acid metabolism, lipid oxidation, appetite control, and energy expenditure, thereby reframing our understanding of its pathophysiological significance in cardiometabolic diseases.

Disruptions in glucagon signaling pathways contribute significantly to the pathogenesis of type 1 and type 2 diabetes (T1DM, T2DM), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)/metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), and obesity [5] [11]. These conditions often manifest as hyperglucagonemia and hepatic glucagon resistance, states whose broader systemic effects are still being elucidated [22]. This expanded understanding is now driving the development of novel therapeutic agents that incorporate glucagon receptor activity alongside other incretin hormones, representing a frontier in metabolic disease pharmacotherapy [11] [23].

Expanded Metabolic Roles of Glucagon

Glucagon in Amino Acid Metabolism

The liver-α-cell axis represents a crucial feedback loop maintaining systemic amino acid homeostasis. Glucagon directly stimulates hepatic amino acid uptake and catabolism, while also promoting ureagenesis—the conversion of ammonia into urea for safe excretion [5] [22]. This process is vital for detoxifying ammonia generated from protein catabolism. When hepatic glucagon signaling is impaired, as occurs in glucagon resistance, it disrupts this axis, leading to hyperaminoacidemia (elevated blood amino acid levels) [5]. This elevated amino acid concentration subsequently triggers excessive glucagon secretion from pancreatic α-cells, creating a pathological cycle [5] [22].

Notably, glucagon-induced amino acid catabolism may have detrimental consequences in chronic metabolic diseases. By increasing the breakdown of amino acids, particularly from skeletal muscle, glucagon can potentially contribute to muscle wasting, thereby supplying substrates for hepatic gluconeogenesis and perpetuating hyperglycemia [5] [22]. This catabolic pathway illustrates how glucagon's amino acid-regulating functions can indirectly sustain elevated blood glucose levels in diabetes.

Glucagon in Lipid Metabolism and Energy Balance

Beyond its classical roles, glucagon exerts significant effects on lipid homeostasis and overall energy balance through multiple mechanisms:

Hepatic Lipid Metabolism: Glucagon promotes hepatic lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation while facilitating cholesterol clearance [5] [22]. Recent research has identified that the RNA-binding protein ALKBH5 regulates the glucagon receptor (GCGR) and mTORC1 signaling through distinct mechanisms, integrating control of both glucose and lipid metabolism [23]. Specifically, ALKBH5 regulates the EGFR-mTORC1 signaling cascade independently of its demethylase activity, thereby influencing lipid homeostasis [23].

Appetite Regulation: Glucagon acts as a satiety signal through the liver–vagal nerve–hypothalamic axis. Studies demonstrate that glucagon decreases food intake in rodent models, while glucagon antibodies have been associated with increased food consumption, highlighting its anorexigenic effect [5].

Thermogenesis: Glucagon encourages heat production by activating brown adipose tissue (BAT), thereby increasing energy expenditure and potentially aiding weight loss [5]. This thermogenic effect, combined with appetite suppression, positions glucagon as a significant regulator of whole-body energy balance.

Table 1: Glucagon's Multi-Organ Metabolic Effects

| Target Organ/Tissue | Primary Metabolic Effects | Signaling Pathways |

|---|---|---|

| Liver | Stimulates gluconeogenesis, glycogenolysis; Enhances amino acid uptake/catabolism, ureagenesis; Promotes lipolysis, fatty acid oxidation, cholesterol clearance | cAMP-PKA, ALKBH5-GCGR, ALKBH5-EGFR-mTORC1 |

| Brain | Decreases food intake; Regulates blood glucose via central nervous system | Liver-vagal nerve-hypothalamic axis |

| Brown Adipose Tissue | Activates thermogenesis; Increases energy expenditure | Sympathetic nervous system activation |

| Pancreas | Paracrine regulation of β-cells; Potential GLP-1 production | cAMP-PKA, intra-islet signaling |

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Canonical and Emerging Signaling Cascades

Glucagon signaling is primarily mediated through the glucagon receptor (GCGR), a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) highly expressed in the liver, kidney, and various other tissues [11]. Upon glucagon binding, GCGR activates adenylate cyclase, leading to increased intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels. This second messenger then activates protein kinase A (PKA) and exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac), which in turn regulate downstream effectors including calcium channels and vesicle trafficking proteins [5] [22].

Recent research has uncovered novel signaling intermediaries, particularly the RNA-binding protein ALKBH5, which integrates glucagon's effects on both glucose and lipid metabolism through two distinct mechanisms [23]:

Glucose Homeostasis: Glucagon-PKA signaling phosphorylates ALKBH5 at Ser362, promoting its translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, where it binds to and stabilizes Gcgr mRNA via m6A demethylation, sustaining GCGR signaling.

Lipid Homeostasis: ALKBH5 independently activates Egfr transcription through demethylase-independent enhancer binding, subsequently upregulating the EGFR-PI3K-mTORC1-SREBP1 pathway to regulate lipid synthesis.

Central Nervous System Integration

The central nervous system (CNS), particularly hypothalamic and brainstem regions, plays a vital role in glucagon-mediated systemic metabolism. Specific neuronal populations in the arcuate nucleus (ARH), ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH), and dorsal vagal complex (DVC) sense metabolic signals including glucose, insulin, and likely glucagon itself to regulate autonomic outflow and endocrine function [24] [25]. Glucagon receptors in the hypothalamus coordinate hepatic glucose production via neural pathways that help sustain overall metabolic balance [5] [22].

Notably, AgRP/NPY neurons in the ARH regulate hepatic glucose production and systemic insulin sensitivity, while POMC neurons mediate glucose-lowering effects and influence renal glucose reabsorption [25]. The VMH is particularly important for counterregulatory hormone responses during hypoglycemia, with SF-1 neurons essential for recovery from insulin-induced hypoglycemia through glucagon and corticosterone secretion [25]. These central regulatory circuits demonstrate the sophisticated integration of glucagon signaling within broader neuroendocrine networks maintaining metabolic homeostasis.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Key Research Models and Techniques

Investigating glucagon's expanded metabolic roles requires sophisticated experimental approaches spanning molecular, cellular, and whole-organism levels. The following methodologies represent cutting-edge techniques in the field:

Table 2: Experimental Approaches for Studying Glucagon Biology

| Methodology | Application | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic lineage tracing & indelible marking | Tracking β-cell and α-cell subtypes over time; Studying cellular plasticity | Revealed β-cell subtypes with varying fitness; Maternal diet effects on offspring β-cell populations [26] |

| High-specificity mass spectrometry | Detecting bioactive GLP-1 (not inactive fragments) | Discovered alpha cells produce significant bioactive GLP-1, especially when glucagon blocked [21] |

| Chemogenetics & Optogenetics | Controlling specific neuronal population activity in live animals | Identified AgRP neurons decrease insulin sensitivity; VMH SF-1 neurons crucial for hypoglycemia recovery [25] |

| Hepatocyte-specific knockout models | Tissue-specific gene function analysis (e.g., Alkbh5-HKO mice) | ALKBH5 regulates GCGR (glucose) and EGFR-mTORC1 (lipid) via distinct mechanisms [23] |

| Enzyme manipulation (PC1/PC2 inhibition) | Studying hormone production pathways in alpha cells | Blocking PC2 (glucagon production) boosted PC1 (GLP-1 production), improving glucose control [21] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Glucagon Signaling Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Alkbh5-HKO mice | Liver-specific ALKBH5 knockout model | Studying tissue-specific regulation of glucose (GCGR) and lipid (EGFR-mTORC1) homeostasis [23] |

| GCGR antagonists | Blocking glucagon receptor signaling | Validating glucagon's role in hyperglycemia; GCGR antagonism lowers blood glucose but increases body weight, hepatic fat [11] |

| PC2 inhibitors | Blocking prohormone convertase 2 enzyme | Inhibiting glucagon production from alpha cells; Surprisingly increases GLP-1 production [21] |

| GalNAc-siRNA technology | Liver-specific gene knockdown therapeutic approach | Hepatic Alkbh5 knockdown reversed hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and MAFLD in db/db mice [23] |

| Insulin-glucagon fusion proteins | Single molecule combining insulin and glucagon activities | Exploits endogenous hepatic switch: insulin dominates at high glucose, glucagon at low glucose [27] |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

Emerging Pharmacological Approaches

The expanding understanding of glucagon biology has catalyzed the development of novel therapeutic agents for metabolic diseases. Unlike earlier strategies that focused solely on glucagon receptor antagonism, contemporary approaches leverage glucagon's beneficial metabolic effects while mitigating its hyperglycemic potential:

Multi-Agonist Therapies: Unimolecular compounds incorporating glucagon receptor activation alongside GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) and/or glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor (GIPR) agonism have demonstrated substantial efficacy. Retatrutide (GCGR/GIPR/GLP-1R triple agonist), mazdutide, and survodutide (both GCGR/GLP-1R dual agonists) have advanced to Phase III clinical trials, showing promising results for weight loss and MASLD/MASH improvement [11] [23].

Stabilized Glucagon Analogs: Research on ultrastable insulin-glucagon fusion proteins demonstrates the potential for exploiting endogenous hepatic switches where "insulin wins" at high glucose levels, while "glucagon wins" at low glucose levels, thereby mitigating hypoglycemic risk [27].

RNA-Targeted Therapies: The identification of ALKBH5 as a coordinator of glucose and lipid metabolism through distinct mechanisms highlights the potential of targeting RNA-binding proteins for metabolic disease treatment [23].

Future Research Directions

Despite significant advances, critical questions remain regarding glucagon's expanded metabolic roles. Future research should focus on:

Glucagon Resistance Mechanisms: Delineating the molecular pathways underlying hepatic and extra-hepatic glucagon resistance across different metabolic diseases [5] [22].

Alpha Cell Plasticity: Further exploration of alpha cell reprogramming capabilities, including the physiological and therapeutic relevance of their GLP-1 production capacity [21].

Central Glucagon Signaling: Elucidating the precise neural circuits and mechanisms through which central glucagon signaling influences peripheral metabolism [24] [25].

Tissue-Specific Effects: Understanding how glucagon signaling is regulated in different tissues (skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, kidney) and its contribution to whole-body metabolic homeostasis [5] [23].

The ongoing clinical development of GCGR-based multi-agonists and continued basic research into glucagon biology will further clarify its role in energy regulation and lipid metabolism, potentially yielding new therapeutic options for obesity, MASLD, and other cardio-kidney-metabolic conditions [11]. As these data emerge, the glucagon-centric perspective on metabolic disease will continue to evolve, potentially transforming our approach to treating these prevalent conditions.

The traditional paradigm of pancreatic islet function delineates a strict division of labor: α-cells produce glucagon to elevate blood glucose, while β-cells secrete insulin to lower it. However, a transformative shift is underway, fueled by the discovery that pancreatic α-cells exhibit significant plasticity, including the capacity to co-produce glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). This whitepaper synthesizes recent advances revealing that α-cells can dynamically alter their hormonal output, upregulating the production of bioactive GLP-1 via the enzyme PC1/3. This review details the molecular mechanisms, quantitative assessments, and experimental methodologies defining this phenomenon, and discusses its profound implications for understanding systemic glucose homeostasis and developing next-generation therapeutics for diabetes.

For decades, the hormonal regulation of blood glucose has been modeled on the opposing actions of insulin and glucagon. Insulin, secreted by pancreatic β-cells in response to elevated blood glucose, promotes glucose uptake and storage. In contrast, glucagon, released from pancreatic α-cells during fasting or hypoglycemia, stimulates hepatic glucose production [2] [5]. This binary model is now recognized as incomplete.

Alpha cell plasticity challenges this conventional view. Emerging evidence demonstrates that α-cells are not terminally differentiated but possess the remarkable ability to adapt their function and hormone profile in response to metabolic cues and disease states [21] [28]. A cornerstone of this plasticity is the co-production of GLP-1, a potent incretin hormone that enhances glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, inhibits glucagon release, and slows gastric emptying [29]. While GLP-1 was traditionally considered a gut-derived hormone, produced and secreted by intestinal L-cells [30], its synthesis within pancreatic islets, particularly by α-cells, is now established as a functionally significant source [21] [31].

This whitepaper explores the molecular basis and functional consequences of α-cell GLP-1 production, framing it within the broader context of islet cell transdifferentiation and hormonal crosstalk. It is intended to equip researchers and drug development professionals with a detailed technical overview of this emerging paradigm.

Molecular Mechanisms of Proglucagon Processing

The production of both glucagon and GLP-1 from a single precursor, proglucagon, is a classic example of tissue-specific post-translational processing.

The Proglucagon Gene and Protein

The proglucagon gene (Gcg) encodes a 160-amino acid precursor polypeptide that contains the sequences for several biologically active peptides, including glucagon, GLP-1, and GLP-2 [29]. The fate of this prohormone is determined by the specific prohormone convertase (PC) enzymes expressed in different tissues.

Tissue-Specific Cleavage

The differential processing of proglucagon in pancreatic α-cells and intestinal L-cells is summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Tissue-Specific Processing of Proglucagon

| Tissue/Cell Type | Key Processing Enzyme | Primary Peptide Products |

|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic α-cell | Prohormone Convertase 2 (PC2) | Glucagon, Major Proglucagon Fragment (MPGF) [29] [30] |

| Intestinal L-cell | Prohormone Convertase 1/3 (PC1/3) | Glicentin, GLP-1, GLP-2, Oxyntomodulin [29] [30] |

The historical view held that pancreatic α-cells exclusively express PC2, thus producing glucagon but not mature GLP-1. This view has been overturned. Recent studies confirm that α-cells can co-express PC1/3, allowing them to process proglucagon into bioactive GLP-1(7-36)NH₂ [21] [31]. This plasticity in processing enzyme usage is a fundamental mechanism enabling α-cells to switch their hormonal output.

The following diagram illustrates the differential processing of proglucagon and the key experimental manipulation of the convertase enzymes.

Enzymatic Switching and Functional Consequences

Research utilizing transgenic mouse models with α-cell-specific inducible deletion of Pcsk2 (encoding PC2) has been pivotal. Campbell et al. demonstrated that blocking PC2 and thus glucagon production did not impair insulin secretion as expected. Instead, α-cells upregulated PC1/3, increased GLP-1 production, and improved glucose tolerance [21] [31]. This "enzymatic switch" from PC2 to PC1/3 represents a built-in rescue mechanism for maintaining insulin secretion and blood glucose control.

Quantitative Evidence and Functional Impact

The physiological relevance of α-cell-derived GLP-1 is supported by robust quantitative data. The table below summarizes key findings from recent studies quantifying GLP-1 in pancreatic tissue and its functional correlation.

Table 2: Quantitative Evidence for α-Cell-Derived GLP-1

| Experimental Model | Key Quantitative Finding | Functional Correlation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human pancreatic tissue (various ages, weights, diabetes statuses) | Human islets contain substantially higher levels of bioactive GLP-1(7-36)NH₂ than mouse islets. | GLP-1 levels positively correlated with rates of insulin secretion. | [21] [31] |

| Mouse model with α-cell-specific PC2 knockout | Upregulation of PC1/3 and a significant increase in GLP-1 production. | Improved glucose tolerance and enhanced insulin secretion. | [21] [31] |

| Single-cell RNA-seq of human non-diabetic and T2D islets | Identification of a distinct α-cell subpopulation ("AB cells") co-expressing GCG (glucagon) and INS (insulin). | AB cells comprised 2.2-6.9% of insulin-positive cells, increasing in T2D; suggests bihormonal potential and transdifferentiation. | [28] |

These data confirm that GLP-1 production in the human pancreas is not a mere artifact but a quantifiable and functionally significant phenomenon. The presence of bioactive GLP-1 in islets and its positive correlation with insulin secretion underscores its role in a paracrine α-to-β cell signaling axis.

Experimental Protocols for Key Investigations

This section outlines detailed methodologies for key experiments that have been instrumental in elucidating α-cell GLP-1 co-production.

Mass Spectrometry Assay for Bioactive GLP-1

Objective: To accurately detect and quantify levels of the bioactive form of GLP-1 (GLP-1(7-36)NH₂) in pancreatic tissue or islet lysates, avoiding cross-reactivity with inactive fragments [21].

Workflow:

- Tissue Preparation: Isolate pancreatic islets from human or mouse donors. Homogenize islets in a buffer containing protease inhibitors to prevent peptide degradation.

- Peptide Extraction: Use acid-ethanol extraction or solid-phase extraction to isolate peptides from the homogenate.

- Immunoaffinity Enrichment: Incubate the peptide extract with antibodies specific for the N-terminus of GLP-1(7-36)NH₂. This step is critical for excluding other proglucagon-derived peptides and inactive C-terminal fragments (e.g., GLP-1(9-36)NH₂).

- Liquid Chromatography (LC): Separate the enriched peptides using reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

- Mass Spectrometry (MS) Analysis: Analyze the eluent using a high-sensitivity mass spectrometer (e.g., tandem MS). Quantify GLP-1(7-36)NH₂ by comparing its signal to a known concentration of a stable isotope-labeled internal standard.

This method's high specificity, achieved through immunoaffinity and mass spectrometry, was crucial for the definitive discovery of bioactive GLP-1 in human islets [21].

α-Cell-Specific Prohormone Convertase Knockout Model

Objective: To determine the specific roles of PC1/3 and PC2 in α-cell proglucagon processing and islet function in vivo [21] [31].

Workflow:

- Genetic Model Generation: Generate transgenic mouse lines with loxP sites flanking critical exons of the Pcsk1 (PC1/3) and Pcsk2 (PC2) genes. Cross these mice with a mouse line expressing Cre recombinase under the control of an α-cell-specific promoter (e.g., Gcg-Cre or Pax6-CreER for inducible systems).

- Induction and Validation: For inducible models, administer tamoxifen to adult mice to activate Cre recombinase and delete the target genes. Validate gene deletion and protein loss using qPCR, immunohistochemistry, and Western blot on isolated islets.

- Phenotypic Characterization:

- Metabolic Phenotyping: Perform glucose tolerance tests (GTT) and insulin tolerance tests (ITT) on knockout and control mice.

- Hormone Secretion Assays: Use isolated islet perfusion or static incubation to measure glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) and glucagon secretion.

- Hormone Level Quantification: Apply the mass spectrometry protocol (4.1) to measure GLP-1 and glucagon levels in knockout islets.

- Data Interpretation: The key finding from this approach was that PC2 knockout improved glucose tolerance via GLP-1, while double knockout of PC1/3 and PC2 abrogated this effect, confirming the critical role of PC1/3 in the compensatory GLP-1 production [21] [31].

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing for α-Cell Heterogeneity

Objective: To identify transcriptomically distinct subpopulations of α-cells and infer cell trajectories in non-diabetic and T2D islets [28].

Workflow:

- Islet Dissociation and Cell Sorting: Dissociate human islets into single-cell suspensions. Use fluorescent cell sorting if specific markers are available.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Use a platform like 10x Genomics to capture single cells, barcode RNA, and prepare sequencing libraries. Perform both single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) and single-nucleus RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) to capture cytoplasmic and nuclear transcripts.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Data Integration and Clustering: Integrate scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq datasets. Perform unsupervised clustering (e.g., Louvain algorithm) to identify cell clusters.

- Subcluster Analysis: Subset the α-cell cluster (GCG+ cells) and re-cluster at high resolution to identify α-cell subtypes.

- Differential Expression and Trajectory Inference: Identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between subclusters. Use RNA velocity and PAGA (Partition-based Graph Abstraction) algorithms to infer potential developmental trajectories and transitions between β-cell and α-cell states.

- Validation: Validate key findings from bioinformatic analysis using RNAscope (in situ hybridization) or immunohistochemistry on pancreatic sections. For example, the discovery of the SMOC1 gene as a marker of β-cell dedifferentiation towards an α-cell-like phenotype was validated in this manner [28].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational workflow for single-cell analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs key reagents and tools essential for investigating α-cell plasticity and GLP-1 biology.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Alpha Cell Plasticity Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| α-Cell-Specific Cre Mouse Models | Enables cell-type-specific gene manipulation (knockout, overexpression) in α-cells in vivo. | Gcg-Cre, Pax6-CreER (tamoxifen-inducible). Critical for studying PC1/3 and PC2 function [31]. |

| High-Specificity GLP-1 Antibodies | Immunoaffinity enrichment for MS, immunohistochemistry (IHC), and immunofluorescence (IF). | Must be specific for N-terminal epitope of GLP-1(7-36)NH₂ to avoid cross-reactivity [21]. |

| Prohormone Convertase Inhibitors | Pharmacological inhibition of PC1/3 or PC2 to validate their roles in proglucagon processing in isolated islet studies. | e.g., PC1/3-specific inhibitors to block GLP-1 production. |

| Single-Cell RNA-seq Kits | Profiling the transcriptome of individual cells to uncover heterogeneity and identify novel subpopulations. | 10x Genomics Chromium platform. Used to identify α-cell subtypes and bihormonal AB cells [28]. |

| Human Pancreatic Islets | Direct ex vivo study of human α-cell biology. Sourced from organ donors (non-diabetic, T2D). | Essential for translational validation of findings from mouse models. Available via programs like HIRN-HPAP [28]. |

| GLP-1 Receptor Agonists (GLP-1RAs) & Antagonists | To probe the functional effects of GLP-1 receptor signaling on β-cells and islet function. | Exendin-9-39 is a common GLP-1R antagonist. |

Discussion and Future Directions