Insulin Analogs in Diabetes Management: A Comprehensive PK/PD Analysis for Drug Development

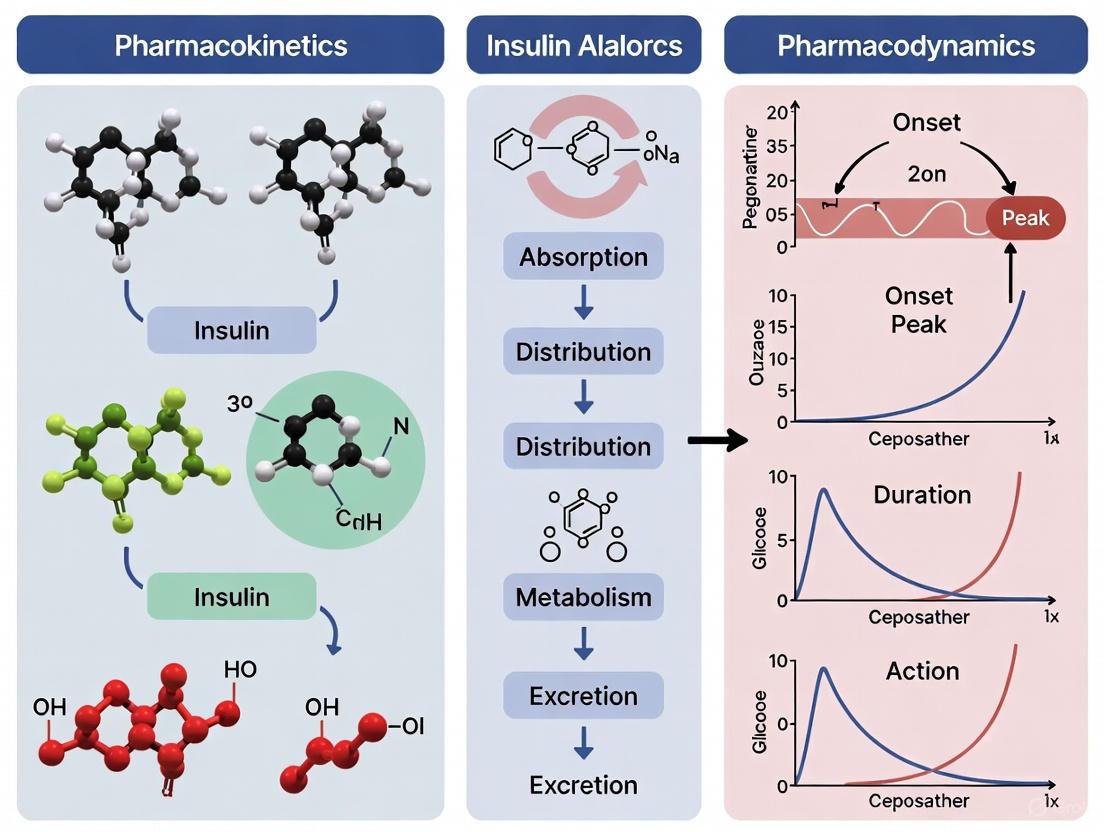

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) properties of modern insulin analogs, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Insulin Analogs in Diabetes Management: A Comprehensive PK/PD Analysis for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) properties of modern insulin analogs, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of insulin analog design, from rapid-acting to ultra-long-acting formulations, and examines the advanced methodologies, including euglycemic clamp studies and mechanism-based PK/PD modeling, used to characterize their efficacy. The content addresses key challenges such as hypoglycemia risk, variability in drug response, and stability issues, while offering optimization strategies for clinical translation. Finally, it presents a comparative evaluation of existing and next-generation analogs, including once-weekly insulins, discussing their validation and implications for future therapeutic development and personalized diabetes treatment regimens.

Engineering Physiologic Profiles: The Structural Basis of Insulin Analog Design

The management of diabetes has been fundamentally shaped by the continuous pursuit of insulin formulations that more closely mimic the body's natural physiologic insulin secretion. Since its landmark discovery and first use in 1922, insulin therapy has evolved through remarkable scientific milestones—from animal-sourced insulins to recombinant human insulin and, most significantly, to the development of structurally engineered analogs with tailored pharmacokinetic properties. This evolution has been driven by the recognition that the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) profiles of traditional human insulin preparations do not adequately replicate the precise temporal pattern of endogenous insulin release, which consists of both basal background secretion and rapid prandial bursts.

The limitations of regular human insulin—characterized by a delayed onset and prolonged duration of action—created challenges in achieving optimal glycemic control without increasing hypoglycemia risk. The advent of recombinant DNA technology enabled protein engineering to modify the insulin molecule itself, leading to analogs designed to overcome these limitations. These designer analogs can be broadly categorized into rapid-acting formulations that accelerate subcutaneous absorption for mealtime coverage and long-acting formulations that provide a flat, stable basal insulin supply. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the performance characteristics of these insulin analogs, underpinned by experimental data and detailed methodologies essential for research and development professionals working at the forefront of metabolic therapeutics.

Comparative Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Profiles

The clinical utility of any insulin preparation is determined by its absorption, distribution, and elimination characteristics, collectively known as pharmacokinetics (PK), and its subsequent glucose-lowering effects, or pharmacodynamics (PD). The following tables synthesize quantitative data from head-to-head comparative studies, euglycemic clamp experiments, and meta-analyses to provide a structured overview of the established and emerging insulin analogs.

Table 1: Pharmacokinetic Properties of Insulin Analogs and Formulations

| Insulin Type | Representative Products | Onset of Action | Peak Concentration (T~max~) | Effective Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Rapid Analogs | Fast-acting insulin aspart (FIASP), Ultra-rapid lispro (URLi) | ~5-15 minutes | 30-60 minutes | 3-5 hours |

| Rapid-Acting Analogs | Insulin aspart, lispro, glulisine | 15-30 minutes | 1-2 hours | 3-5 hours |

| Short-Acting (Regular) | Human insulin | 30-60 minutes | 2-4 hours | 6-8 hours |

| Intermediate-Acting | NPH insulin | 1-3 hours | 5-8 hours | 13-18 hours |

| Long-Acting Analogs | Glargine U-100, Detemir, Degludec | 1-4 hours | Relatively flat | 18-24 hours (Detemir) to >42 hours (Degludec) |

| Once-Weekly Analog | Insulin Efsitora alfa (LY3209590) | ~1 day | Low peak-to-trough ratio (1.13) | ~7 days (Half-life: 15-16 days) |

The data in Table 1 illustrate how analog engineering has successfully modulated the absorption profile. Rapid-acting analogs achieve faster onset and higher peak concentrations by resisting hexamer formation, while long-acting analogs utilize strategies like albumin binding (detemir) and multi-hexamer formation (degludec, glargine) to create a stable, depot effect. The recent development of once-weekly insulin Efsitora alfa, with a half-life of 15-16 days and a low peak-to-trough ratio of 1.13, represents a significant advance in reducing dosing frequency and glycemic variability [1].

Table 2: Pharmacodynamic Outcomes from Comparative Clinical Studies

| Comparison | Study Design | Key Efficacy Endpoint (Mean Difference) | Key Safety Endpoint | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AID-URAI vs. AID-RAI | Meta-analysis of 16 RCTs (n=664, T1D) | TIR: +1.07% (95% CI: 0.11 to 2.02), p=0.029 | TBR (<3.9 mmol/L): -0.35% | [2] |

| URAIs (FIASP/URLi) vs. RAIs | Multiple RCTs in Automated Insulin Delivery (AID) | Improved postprandial glucose control | No increased risk of severe hypoglycemia or DKA | [2] |

| Generic vs. Brand Lispro 25 | Randomized crossover (n=52, healthy) | GIR~max~: 4.47 vs 4.12 mg/kg/min (T vs R) | No significant hypoglycemia or SAEs; Bioequivalence demonstrated | [3] |

| Oral ORMD-0801 (16 mg) vs. SC Insulin | Phase I clamp (n=20, healthy) | GIR~max~: 3.87 vs 3.51 mg/kg/minAUC~GIR0-11h~: 26.98 vs 23.74 h·mg/kg/min | SC-equivalent dose: 6.53 ± 3.97 IU | [4] |

| Once-Weekly Efsitora | Phase I/II in T2D (Japanese cohort) | Decreased fasting glucose with single doses (5-20 mg); Stable glycemic control with multi-dose | No severe hypoglycemic events; All AEs mild and unrelated | [1] |

The pharmacodynamic outcomes in Table 2 highlight subtle but meaningful clinical differences. Automated insulin delivery (AID) systems using ultra-rapid-acting analogs (URAIs) show a small but statistically significant improvement in Time-in-Range (TIR) without increasing hypoglycemia risk [2]. Bioequivalence studies confirm that generic insulin lispro products have nearly identical PK/PD profiles to their brand-name counterparts, supporting their interchangeability and potential to reduce healthcare costs [3]. Investigations into novel delivery routes, such as oral insulin ORMD-0801, demonstrate measurable pharmacodynamic effects, though with low relative bioavailability (0.53-0.94%) [4].

Experimental Protocols: The Gold Standard for Insulin Assessment

The Euglycemic Glucose Clamp Technique

The euglycemic glucose clamp remains the gold standard methodology for rigorously characterizing the PK/PD properties of insulin formulations. It allows for the precise quantification of insulin action by maintaining a constant plasma glucose level, thereby isolating the drug's effect from confounding metabolic variables.

Detailed Clamp Procedure: As implemented in a bioequivalence study of insulin lispro [3], the protocol involves:

- Subject Preparation: Healthy male volunteers (n=52) are fasted overnight. Baseline blood samples are collected for glucose and C-peptide measurement to confirm endogenous insulin suppression during the clamp.

- Insulin Administration: A single subcutaneous dose (0.3 IU/kg) of the test or reference insulin preparation is administered.

- Glucose Clamping: Blood glucose is measured frequently (e.g., every 5-120 minutes over 24 hours). A variable 20% glucose solution is infused intravenously at a rate adjusted to maintain the target blood glucose level (typically within ±10% of the baseline minus 0.28 mmol/L) [3].

- Pharmacokinetic Sampling: Blood is drawn at predetermined time points (e.g., -30 min to 24h post-dose) to measure plasma insulin analog concentration using high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) [3].

- Data Analysis: The primary pharmacodynamic endpoint is the Glucose Infusion Rate (GIR) over time. Key parameters include:

- GIR~max~: The maximum glucose infusion rate, reflecting peak insulin action.

- AUC~GIR0-t~: The area under the GIR-time curve, reflecting the total glucose-lowering effect.

- PK parameters like C~max~ (maximum concentration) and AUC~Ins0-t~ (total exposure) are calculated from the plasma insulin concentration data.

Automated Insulin Delivery (AID) System Trials

For evaluating insulins in a clinically relevant setting, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of AID systems (closed-loop systems) are employed.

Standard Protocol [2]:

- Participant Recruitment: Patients with type 1 diabetes are recruited and their existing insulin therapy is stabilized.

- Randomization & Intervention: Participants are randomized to use an AID system configured with either an ultra-rapid-acting insulin (URAI) or a standard rapid-acting insulin (RAI) for the trial duration.

- Outcome Measurement: The primary outcome is typically the percentage of Time-in-Range (TIR), defined as the duration spent in a glucose range of 3.9-10.0 mmol/L, as measured by continuous glucose monitoring (CGM). Key secondary outcomes include Time-Below-Range (TBR), Time-Above-Range (TAR), and the incidence of severe hypoglycemia or diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).

- Meta-Analysis: Data from multiple RCTs are pooled in a meta-analysis to provide a higher level of evidence, as seen in the 2025 analysis that included 16 trials and 664 participants [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Insulin PK/PD Research

| Item | Specific Example | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Insulin Analogs | Insulin aspart, lispro, glulisine, glargine, degludec | The active pharmaceutical ingredients under investigation for their PK/PD properties. |

| Euglycemic Clamp System | Variable IV glucose infusion pump, frequent glucose analyzer (e.g., glucose oxidase method) | The core experimental setup for measuring the pharmacodynamic effect of insulin via the Glucose Infusion Rate (GIR). |

| Analytical Chromatography | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) system with Mass Spectrometer (LC-MS/MS) | Gold standard for precise quantification of insulin analog concentrations in plasma for pharmacokinetic analysis [3]. |

| Immunoassays | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) for C-peptide and insulin | Used to monitor endogenous insulin suppression (via C-peptide) and measure insulin levels in biological samples [3]. |

| Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGM) | Commercial CGM systems (e.g., Dexcom, Medtronic) | Provides high-resolution, real-world glycemic data (TIR, TBR, TAR) in outpatient clinical trials [2]. |

| Animal Models | Rats, Dogs, Pigs (non-diabetic and diabetic strains) | Used in pre-clinical studies to characterize initial PK/PD profiles and assess safety before human trials [5]. |

| PK/PD Modeling Software | MONOLIX, WinNonlin | Industry-standard software for non-linear mixed-effect modeling and bioequivalence analysis of complex PK/PD data [6] [3]. |

Molecular Mechanisms of Action and Signaling Pathways

Despite structural modifications, insulin analogs primarily exert their effects through the same fundamental mechanism as native human insulin: binding to and activating the insulin receptor (IR). The metabolic effects are mediated through downstream signaling pathways that promote glucose uptake and utilization.

Key Mechanistic Insights:

- Receptor Binding and Specificity: While engineered for altered pharmacokinetics, most analogs retain high specificity for the insulin receptor. However, minor structural changes can affect their binding affinity to the Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 Receptor (IGF-1R), a phenomenon investigated for its potential mitogenic implications. For instance, insulin glargine's metabolites exhibit a lower IGF-1R binding affinity compared to human insulin, whereas insulin detemir and degludec have a reduced affinity [7].

- Downstream Consequences: Activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway is responsible for the primary metabolic effects, including stimulation of glucose transporter (GLUT4) translocation to the cell membrane, enhancing cellular glucose uptake. Activation of the MAPK pathway can influence cell growth and proliferation [7].

- Mitogenic Potency: In vitro assessments are conducted to compare the mitogenic potency of analogs relative to human insulin. These studies have shown that insulin glargine has a higher mitogenic potency, attributed to its increased IGF-1R affinity, though its active metabolites (M1) exhibit a lower affinity. The long-term clinical significance of these in vitro findings remains unclear, as large epidemiological studies have not confirmed an associated increased cancer risk in patients [7].

The pursuit of physiologic insulin secretion has driven the development of a sophisticated arsenal of insulin analogs, each engineered with distinct PK/PD profiles to meet specific therapeutic needs. The experimental data clearly demonstrate that ultra-rapid analogs offer incremental improvements in postprandial glucose and time-in-range within AID systems, while long-acting and weekly analogs provide more stable basal coverage with reduced injection burden. The gold-standard euglycemic clamp methodology continues to be indispensable for the precise characterization of these properties during drug development.

Future innovation will likely focus on further optimizing the kinetic profiles of prandial insulins, extending the duration of basal insulins, and exploring non-invasive delivery systems like oral insulin. Furthermore, the integration of these advanced analogs with increasingly intelligent automated delivery systems represents the most promising path toward achieving fully physiologic insulin replacement, ultimately improving the quality of life for millions of people with diabetes worldwide.

The strategic engineering of insulin analogs through amino acid modifications represents a cornerstone of modern therapeutic development for diabetes mellitus. These deliberate structural alterations aim to optimize pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) profiles by fundamentally changing the self-association behavior of insulin molecules. This guide provides a comparative analysis of engineered insulin analogs, detailing how specific amino acid substitutions impact oligomerization, stability, and ultimately, clinical efficacy. We summarize critical experimental data and methodologies used to characterize these analogs, offering a resource for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in protein engineering and therapeutic design.

Insulin is a peptide hormone that exists in various states of self-assembly—monomers, dimers, and hexamers—with the monomer being the biologically active form capable of crossing the vascular endothelium [8]. In native human insulin, the propensity to form hexamers is a significant rate-limiting step for absorption after subcutaneous injection, leading to delays in its metabolic action [8]. Molecular engineering of insulin analogs focuses on introducing specific amino acid modifications to alter these self-association properties, thereby creating fast-acting or long-acting therapeutic profiles that more closely mimic physiological insulin secretion [9] [10].

The rationale for these structural changes is rooted in the thermodynamics of protein-protein interactions. By destabilizing dimer and hexamer formation, rapid-acting analogs are absorbed more quickly. Conversely, strategies that stabilize hexamers or promote precipitation at physiological pH lead to a prolonged release of insulin, forming the basis for long-acting basal analogs [11] [10]. This guide systematically compares these engineering strategies, their outcomes on self-association, and the experimental paradigms used to validate them.

Comparative Analysis of Insulin Analog Engineering

The following section provides a detailed comparison of how different amino acid modifications lead to distinct pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic outcomes.

Table 1: Comparison of Rapid-Acting Insulin Analogs and Their Engineering Strategies

| Analog Name | Amino Acid Modifications | Impact on Self-Association | Key Pharmacokinetic (PK) & Pharmacodynamic (PD) Outcomes | Primary Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin Lispro | Reversal of proline (B28) and lysine (B29) on the B-chain [8]. | Weakens self-association; reduces dimerization constant 200-300 fold vs. human insulin [8]. | PK: Peak serum concentration at ~42 min [10].PD: Time to peak action ~99 min; reduced postprandial glucose excursions [8]. | Euglycemic clamp studies in healthy subjects [10]. |

| Insulin Aspart | Proline at B28 replaced with aspartic acid [8]. | Reduces self-association of monomers; hexamers dissociate rapidly [8]. | PK: Absorbed twice as quickly as human insulin [10].PD: Time to peak action ~94 min [8]. | Double-blind, crossover euglycemic clamp trials [8]. |

| Insulin Glulisine | Asparagine at B3 replaced with lysine; lysine at B29 replaced with glutamic acid [9] [8]. | Introduces charge repulsion; decreases isoelectric point (pI) to 5.1, enhancing solubility and reducing hexamer formation [9] [11]. | PK: Onset of absorption 20-30 min earlier than human insulin [8].PD: Shorter duration of action [9]. | Euglycemic clamp studies comparing absorption rates [8]. |

Table 2: Comparison of Long-Acting Insulin Analogs and Their Engineering Strategies

| Analog Name | Amino Acid Modifications | Impact on Self-Association/Formulation | Key Pharmacokinetic (PK) & Pharmacodynamic (PD) Outcomes | Primary Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin Glargine | Glycine for asparagine at A21; two arginines added to B-chain C-terminus (B31 and B32) [9] [8]. | Shifts isoelectric point from pH 5.4 to 6.7, causing precipitation at physiological pH for prolonged release [8] [10]. | PK: Slow, consistent release over ~24 hours [8].PD: Relatively peakless, flat action profile [10]. | Clinical trials comparing time-action profiles vs. NPH insulin [8]. |

| Insulin Detemir | Threonine at B30 removed; lysine at B29 acylated with a myristic acid (C14) chain [9] [10]. | Promotes increased self-association and reversible albumin binding via the fatty acid chain, buffering plasma concentration [8] [10]. | PK: Protracted action via albumin binding [10].PD: Duration of action up to 24 hours; reduced within-subject variability [8]. | Euglycemic clamp studies and variability analyses [8]. |

| Insulin Icodec | (Not detailed in results, but mentioned as a once-weekly analog) [12]. | Engineered for strong albumin binding and stable depot formation for ultra-long action [12]. | PK: Once-weekly subcutaneous administration [12].PD: Sustained glycemic control over 7 days [12]. | PK/PD modeling analysis of phase 3a ONWARDS trials [12]. |

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Self-Association and Efficacy

Robust experimental methodologies are critical for validating the engineered properties of insulin analogs. The following protocols are standards in the field.

Analytical Ultracentrifugation

- Purpose: To directly monitor the self-association properties of insulin analogs under various formulation conditions (e.g., with zinc ions or phenolic preservatives like m-cresol) [13].

- Protocol Details: Equilibrium and velocity analytical ultracentrifugation are employed. The process involves subjecting insulin samples to a high centrifugal force. Sedimentation velocity experiments measure the rate at which molecules move, providing the apparent sedimentation coefficient (s*). For instance, under formulation conditions with zinc and m-cresol, insulin analogs typically sediment at 2.9-3.1 S, corresponding to the hexameric form [13].

- Key Findings: Studies have demonstrated that despite mutations that destabilize self-assembly (e.g., in the B27-B29 region), the presence of both zinc and m-cresol can override these effects, stabilizing the hexameric structure necessary for formulation [13].

Euglycemic Glucose Clamp

- Purpose: Considered the gold standard for assessing the pharmacodynamic (PD) profile of insulin analogs by measuring the glucose infusion rate (GIR) required to maintain stable blood glucose levels after insulin administration [6] [3].

- Protocol Details: This is often conducted in healthy volunteers or patients in a clinical setting. After a subcutaneous injection of the test insulin analog, blood glucose levels are frequently monitored (e.g., every 5-10 minutes initially). A variable intravenous infusion of glucose is adjusted in real-time to maintain euglycemia. The GIR is recorded over time (e.g., 24 hours) to generate a time-action profile [3].

- Data Output: Key PD parameters include the maximum GIR (GIRmax) and the area under the GIR curve (GIRAUC), which reflect the potency and overall activity of the insulin, respectively. The time to peak GIR indicates the onset of action [6] [3]. This method was pivotal in showing that rapid-acting analogs like lispro and aspart have a significantly earlier and higher peak activity compared to regular human insulin [8] [10].

Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) Modeling

- Purpose: To develop mechanistic models that link insulin pharmacokinetics (serum concentration over time) to its pharmacodynamic effects (glucose utilization) [6].

- Protocol Details: Data from euglycemic clamp studies are digitized and modeled using specialized software like MONOLIX. The PK model often describes subcutaneous absorption via sequential first-order processes and linear elimination. The PD component can use indirect response models to capture the maximum glucose stimulation (Smax) and the insulin concentration producing 50% of Smax (SC50) [6].

- Application: These models allow for the quantitative comparison of different insulin analogs and can predict outcomes in clinical scenarios, such as switching from daily basal insulin to once-weekly icodec [12].

Self-Association Interactions using Mass Spectrometry (SIMSTEX)

- Purpose: To determine self-association equilibrium constants for proteins and their analogs in solution [14].

- Protocol Details: SIMSTEX is a variation of the PLIMSTEX technique. It involves titrating a protein into a solution and using hydrogen/deuterium exchange (H/D exchange) mass spectrometry to monitor the kinetics of deuterium uptake. The changes in exchange rates are fit to a model to determine affinity constants for self-association [14].

- Key Findings: This method has shown that mutants like insulin lispro and AspB9 have a lower propensity for self-association, correlating with faster action in vivo, while others like GlnB13 have an increased tendency to associate, potentially slowing their action [14].

Visualization of Key Concepts

Insulin Signaling Pathway and Cellular Glucose Uptake

The following diagram illustrates the canonical insulin signaling pathway that is activated upon binding of insulin monomers to its receptor, culminating in glucose uptake.

(Diagram Title: Insulin Signaling and GLUT4 Translocation Pathway)

Experimental Workflow for Insulin Analog Characterization

This diagram outlines a logical workflow for the key experimental methods used in the development and characterization of engineered insulin analogs.

(Diagram Title: Insulin Analog R&D Experimental Workflow)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key reagents and their critical functions in insulin analog research, as derived from the experimental protocols cited.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Insulin Analog Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Context from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Zinc Ions (Zn²⁺) | Promotes and stabilizes the formation of insulin hexamers in formulations, which is crucial for the delayed absorption of certain analogs [13] [9]. | Used in formulations of insulin glargine and is a key component in ultracentrifugation studies to mimic formulation conditions [13] [8]. |

| Phenolic Preservatives (e.g., m-cresol) | Acts as a ligand that binds to insulin and stabilizes the hexameric conformation, overriding destabilizing mutations in rapid-acting analogs for shelf stability [13]. | Critical in analytical ultracentrifugation experiments to demonstrate hexamer formation under formulation conditions [13]. |

| Protamine | A protein used to complex with insulin, forming a suspension that delays absorption; used in NPH insulin and premixed analog formulations [3] [10]. | A key component in premixed analogs like insulin lispro protamine suspension [3]. |

| Recombinant Protein Expression Systems (e.g., E. coli) | Enable the large-scale production of recombinant human insulin and its engineered analogs, ensuring purity and consistency for research and therapy [11]. | The foundational technology that enabled the production of the first FDA-approved recombinant insulin, Humulin [11]. |

| Albumin | A serum protein used in in vitro assays to study the binding and protracted mechanism of action of albumin-binding analogs like insulin detemir [10]. | The binding of insulin detemir to albumin is a key part of its prolonged duration and reduced variability [8] [10]. |

The strategic application of amino acid modifications has enabled the rational design of insulin analogs with tailored dissociation kinetics and therapeutic profiles. As evidenced by the comparative data, single or double substitutions in the B-chain are sufficient to profoundly alter self-association, enabling either rapid postprandial coverage or sustained basal activity. The continued evolution of this field—exemplified by the emergence of once-weekly basal insulins and glucose-responsive analogs—relies on the sophisticated experimental toolkit outlined herein, including advanced biophysical characterization, clinical clamp studies, and mechanistic PK/PD modeling. Future engineering efforts will likely leverage these established principles to further enhance the stability, safety, and physiological fidelity of insulin replacement therapy.

The management of diabetes mellitus relies heavily on insulin therapy, with ongoing research focused on developing analogs that more closely mimic physiological insulin secretion. The fundamental goal of insulin analog design is to optimize pharmacokinetic (PK) profiles—how the body affects a drug—and pharmacodynamic (PD) responses—how the drug affects the body—to achieve superior glycaemic control while minimizing adverse effects, particularly hypoglycaemia [15]. Over the last two decades, significant developments in insulin pharmacology have produced analogs with improved PK and PD properties that better replicate physiological insulin patterns in the liver, skeletal muscle, and other tissues [15].

Insulin analogs are strategically engineered through molecular modifications of the native insulin structure, altering properties such as self-assembly, solubility, and receptor binding affinity [16]. These modifications yield formulations with tailored absorption rates and durations of action, classified primarily as rapid-acting, long-acting, and premixed analogs. Understanding the structural basis for these classifications, the experimental methodologies used to evaluate them, and their resulting clinical performance is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working to advance diabetes therapeutics.

The primary structure of insulin, showing the A and B chains connected by disulfide bonds. Key modification sites for analog engineering are highlighted.

Classification and Molecular Engineering of Insulin Analogs

Structural Foundations and Design Principles

Insulin is a small peptide hormone with a molecular mass of approximately 5808 Daltons, consisting of two peptide chains—an A chain (21 amino acids) and a B chain (30 amino acids)—connected by two disulfide bonds [16]. The native form exists as hexamers that dissociate into active monomers upon subcutaneous injection. Analog design exploits this self-assembly behavior by introducing amino acid substitutions that either destabilize hexamer formation (for rapid-acting analogs) or promote stable depot formation (for long-acting analogs) [16]. These modifications alter the isoelectric point, solubility, and binding characteristics to achieve desired PK/PD profiles.

Categories of Insulin Analogs

| Insulin Category | Primary Mechanism of Action | Key Structural Modifications | Representative Agents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid-Acting | Reduced self-assembly for faster absorption | Amino acid substitutions at B28, B29, or B3 to prevent hexamer formation | Insulin lispro, aspart, glulisine, faster aspart [16] [17] |

| Long-Acting | Enhanced hexamer stability or albumin binding for prolonged release | Addition of arginine residues, fatty acid side chains, or isoelectric point shift | Insulin glargine, detemir, degludec [16] |

| Premixed | Fixed combination of rapid- and intermediate-acting components | Biphasic formulation with different dissolution profiles | Insulin lispro 25/75, aspart 30/70 [3] |

Experimental Methodologies for Evaluating Insulin Analogs

The Euglycemic Clamp Technique

The euglycemic glucose clamp is considered the gold standard for assessing the pharmacodynamic properties of insulin formulations [3]. This procedure involves intravenous infusion of insulin while simultaneously administering a variable-rate glucose infusion to maintain blood glucose at a constant baseline level (typically within ±10% of target). The glucose infusion rate (GIR) required to maintain euglycemia serves as a direct measure of insulin action over time [3]. This method provides precise, reproducible data on the onset, peak, and duration of insulin action, making it indispensable for comparative studies of insulin analogs.

Experimental workflow for a euglycemic clamp study to assess insulin pharmacodynamics.

Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Modeling

Mechanistic PK/PD modeling provides a quantitative framework for comparing insulin analogs. These models typically describe insulin absorption via sequential first-order processes, linear elimination, and effects on glucose utilization using biophase, indirect response, or receptor down-regulation components [6]. Key parameters include maximum glucose stimulation (Smax), sensitivity (SC50), and nonlinear clearance (Km) [6]. Modeling reveals that while PK parameters—particularly absorption rates—vary significantly between insulin types, many share common PD parameters related to receptor binding and glucose transporter activation [6] [18].

Comparative Analysis of Insulin Formulations

Rapid-Acting Insulin Analogs

Rapid-acting analogs are designed for prandial glucose control, with modifications that accelerate subcutaneous absorption. Faster aspart, an advanced rapid-acting formulation, contains niacinamide and L-arginine to further enhance absorption, providing earlier onset and greater early insulin exposure compared with traditional insulin aspart [17]. Real-world evidence from a large retrospective cohort study demonstrated that patients with type 1 diabetes switching to faster aspart experienced significant reductions in HbA1c and hypoglycaemia rates compared to those using other rapid-acting analogs [17].

Table 1: Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Properties of Rapid-Acting Insulin Analogs

| Analog | Onset of Action | Peak Action | Duration | Key Structural Features | Clinical Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin Lispro | 15-30 min | 30-90 min | 3-5 hours | Pro(B28)→Lys, Lys(B29)→Pro [16] | Reduced postprandial glucose excursions |

| Insulin Aspart | 10-20 min | 60-90 min | 4-6 hours | Pro(B28)→Aspartic acid [17] | Improved PPG control |

| Insulin Glulisine | 10-15 min | 60-90 min | 3-5 hours | Lys(B3)→Glu, Glu(B29)→Lys [16] | Rapid dissociation into monomers |

| Faster Aspart | 5-10 min | 60-90 min | 4-6 hours | Niacinamide + L-arginine [17] | Superior HbA1c reduction, lower hypoglycaemia risk |

Long-Acting Insulin Analogs

Long-acting analogs provide basal insulin coverage, with modifications that delay absorption and extend duration. Insulin glargine incorporates two additional arginine residues and a shifted isoelectric point (from pH 5.4 to 6.7), causing precipitation at neutral subcutaneous tissue pH and forming a sustained-release depot [16]. Insulin degludec features a fatty acid side chain that promotes multi-hexamer formation, resulting in an ultra-long duration exceeding 42 hours [16]. Emerging once-weekly basal insulins like icodec and efsitora represent the next frontier in extended-duration therapy, potentially improving adherence through reduced injection frequency [16].

Table 2: Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Properties of Long-Acting Insulin Analogs

| Analog | Onset of Action | Peak Action | Duration | Key Structural Features | Clinical Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin Glargine | 1-2 hours | Relatively flat | 20-24 hours | Arg(B31)-Arg(B32), IEP shift to 6.7 [16] | Stable basal coverage, reduced hypoglycaemia |

| Insulin Detemir | 1-2 hours | Relatively flat | 16-24 hours | Fatty acid chain (albumin binding) [16] | Weight-neutral profile |

| Insulin Degludec | 1-2 hours | Peakless | >42 hours | Fatty acid side chain, multi-hexamer formation [16] | Ultra-long duration, flexible dosing |

| Insulin Icodec | 1-2 hours | Peakless | ~7 days | Strong albumin binding, reduced receptor affinity [16] | Once-weekly dosing |

Premixed Insulin Analogs

Premixed analogs combine rapid- and intermediate-acting components in fixed ratios, simplifying regimen complexity. Insulin lispro 25 (25% insulin lispro, 75% insulin lispro protamine suspension) provides both prandial and basal coverage in a single injection [3]. Bioequivalence studies using euglycemic clamp methodology have demonstrated comparable PK/PD profiles between generic and brand-name premixed formulations, with 90% confidence intervals for AUC0-t, Cmax, GIRmax, and GIRAUC0–24h falling within 80%-125% equivalence boundaries [3]. This supports their interchangeability in clinical practice, potentially reducing treatment costs.

Emerging Innovations and Future Directions

Next-Generation Insulin Analogs

Research continues to address remaining challenges in insulin therapy through several innovative approaches. Glucose-responsive insulins represent a promising frontier, designed to modulate insulin release in response to blood glucose concentrations, thereby reducing hypoglycaemia risk [16]. Hepato-preferential analogs aim to restore the physiological insulin gradient that prioritizes hepatic delivery, potentially improving glucose homeostasis with reduced peripheral effects [16]. Additionally, ultra-stable analogs resistant to fibrillation and aggregation are under development to enhance thermal stability, eliminating refrigeration requirements and improving accessibility in resource-limited settings [16].

Advanced Delivery Systems

Technological advancements complement analog improvements, with hybrid closed-loop systems now becoming standard of care for type 1 diabetes in some regions [15]. These systems integrate continuous glucose monitoring with automated insulin delivery, optimizing glycemic control while reducing user burden. When paired with modern rapid-acting analogs like faster aspart, these systems demonstrate enhanced performance, though they require careful optimization of pump settings to account for the faster absorption profiles [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Methodologies for Insulin Studies

| Reagent/Methodology | Primary Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Euglycemic Clamp System | Gold standard PD assessment | Quantifies glucose infusion rate (GIR) to maintain euglycemia during insulin infusion [3] |

| HPLC-Mass Spectrometry | High-sensitivity insulin quantification | Measures plasma concentration of insulin analogs for PK analysis [3] |

| ELISA for C-peptide | Endogenous insulin secretion assessment | Monitors residual pancreatic function and suppression during exogenous insulin studies [3] |

| MONOLIX/WinNonlin | PK/PD modeling software | Performs nonlinear mixed-effects modeling and bioequivalence testing [6] [3] |

| Glucose Oxidase Assay | Real-time glucose measurement | Provides immediate feedback for glucose clamp procedures [3] |

The insulin signaling pathway, from receptor binding to GLUT4 translocation and glucose uptake.

The systematic cataloging of insulin formulations through rigorous PK/PD analysis reveals a sophisticated landscape of molecular engineering tailored to specific therapeutic needs. Rapid-acting analogs prioritize accelerated absorption for prandial control, long-acting analogs focus on sustained release for basal coverage, and premixed formulations balance both needs in simplified regimens. The euglycemic clamp technique remains indispensable for comparative evaluation, while emerging innovations—including once-weekly formulations, glucose-responsive systems, and hepato-preferential analogs—promise to further transform diabetes management. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these principles and methodologies provides a foundation for advancing the next generation of insulin therapeutics.

The goal of insulin replacement therapy is to mimic the normal physiologic pattern of insulin secretion, which comprises a stable basal level with rapid prandial surges [19] [20]. Achieving this with exogenous insulin was historically limited by the pharmacokinetic properties of subcutaneously administered human insulin, which does not replicate this ideal profile [21]. The engineering of insulin analogues has been a pivotal advancement in diabetes treatment, designed specifically to alter the absorption kinetics following subcutaneous injection [22]. The mechanisms of protraction—the processes that extend the duration of action—are fundamental to developing effective basal insulins. This guide provides a detailed comparison of the three primary principles used to prolong the action of insulin analogues: albumin binding, precipitation at the injection site, and exploitation of altered isoelectric points. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this document synthesizes pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data and outlines key experimental methodologies used in this field.

Comparative Analysis of Protraction Mechanisms

The following table summarizes the core mechanisms, molecular modifications, and key pharmacokinetic profiles of the principal long-acting insulin analogues.

Table 1: Comparison of Protraction Mechanisms in Long-Acting Insulin Analogues

| Analogue (Trade Name) | Core Protraction Mechanism | Key Molecular Modifications | Reported Duration of Action (Hours) | Key PK/PD Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin Detemir (Levemir) [20] [22] | Albumin Binding | B29 lysine coupled with a C14 fatty acid chain; B30 threonine omitted. | Up to 24 [21] | Predictable, flat profile; high degree of reversible albumin binding in tissue and circulation. |

| Insulin Glargine (Lantus) [16] [20] | Precipitation & Altered Isoelectric Point | A21 asparagine replaced by glycine; two arginines added to B-chain C-terminus (B31 & B32). | ~24 [21] | Precipitation at neutral pH creates a depot; isoelectric point shifted from 5.4 to 6.7. |

| Insulin Degludec (Tresiba) [16] | Multi-Hexamer Chain Formation | B29 lysine coupled with a C16 fatty diacid; B30 threonine omitted. | >24 (Ultra-long) [16] | Forms soluble multi-hexamer chains upon injection, resulting in a slow, continuous release. |

Detailed Mechanism Breakdown and Experimental Data

Mechanism 1: Albumin Binding

This approach prolongs insulin action by facilitating reversible binding to the abundant albumin protein in the subcutaneous tissue and plasma.

- Molecular Engineering: Insulin detemir is engineered with a C14 fatty acid (myristic acid) side chain covalently attached to the B29 lysine residue, and the terminal B30 threonine is removed [20] [22]. The fatty acid side chain enables the analogue to bind reversibly to albumin.

- Mechanism of Action: Upon subcutaneous injection, the fatty acid chain promotes self-association into di-hexamers [22]. More significantly, the fatty acid moiety allows for high-affinity binding to albumin at the injection site and in the bloodstream. This binding creates a large, stable circulating reservoir of insulin. Only the free, unbound fraction is pharmacologically active at the insulin receptor. The slow dissociation from albumin provides a steady, continuous release of insulin, resulting in a prolonged and predictable duration of action [20] [22].

- Experimental Data: Euglycemic clamp studies, the gold standard for assessing insulin pharmacodynamics, demonstrate that insulin detemir provides a relatively flat and stable time-action profile with low intra-patient variability [21] [22]. This predictable glucose-lowering effect is a key clinical advantage attributed to the albumin-binding mechanism.

Mechanism 2: Precipitation and Altered Isoelectric Point

This strategy involves formulating an insulin that is soluble in the vial but forms a precipitate upon injection, creating a subcutaneous depot.

- Molecular Engineering: Insulin glargine incorporates two key changes: a glycine substitution at position A21 and the addition of two arginine residues to the C-terminus of the B-chain [16] [20]. These modifications shift the isoelectric point of the molecule from pH 5.4 to 6.7 [20].

- Mechanism of Action: Insulin glargine is formulated in an acidic solution (pH 4) where it is fully soluble [16]. After subcutaneous injection into the neutral pH environment (~7.4) of the tissue, the insulin molecules precipitate into stable hexamers [20]. This precipitate forms a depot at the injection site. The prolonged duration of action is achieved through the slow dissolution of this precipitate and the subsequent enzymatic cleavage of the arginine residues in the circulation, which releases active insulin monomers over an extended period [16] [22].

- Experimental Data: Pharmacodynamic profiles from clamp studies confirm that insulin glargine provides a relatively peakless, 24-hour basal insulin supply [20] [21]. Its onset of action is approximately 1-2 hours, and its duration is close to 24 hours in most patients, making it suitable for once-daily dosing [21].

Emerging and Future Protraction Mechanisms

Research continues to develop insulins with even more optimized profiles.

- Multi-Hexamer Chain Formation: Insulin degludec utilizes a different mechanism. Its modification with a C16 fatty diacid leads to the formation of soluble multi-hexamer chains upon subcutaneous injection [16]. These chains slowly dissociate into monomers, providing an ultra-long and stable action profile exceeding 24 hours [16].

- Once-Weekly Insulins: The field is advancing towards once-weekly basal insulins, such as insulin Icodec and Efsitora [16]. These analogues represent the next frontier in protraction technology, though their specific molecular mechanisms were not detailed in the sourced results.

The following diagram illustrates the structural relationships and core mechanisms of the protraction strategies discussed.

Essential Experimental Protocols for Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Profiling

A robust understanding of insulin analogue performance relies on standardized, high-fidelity experimental methods. The following section details key protocols.

The Euglycemic Clamp Technique

The euglycemic glucose clamp is the gold standard method for assessing the pharmacodynamics (glucose-lowering effect) of insulin [23].

- Objective: To quantify the time-action profile of an insulin formulation by measuring the glucose infusion rate (GIR) required to maintain a constant target blood glucose level despite the exogenous insulin administration.

- Detailed Workflow [23]:

- Baseline Period: After an overnight fast, baseline blood glucose and C-peptide levels are measured.

- Insulin Administration: A standardized dose (e.g., 0.3 U/kg) of the test insulin is administered subcutaneously.

- Clamp Initiation: A variable intravenous infusion of 20% glucose is started. The goal is to maintain blood glucose at a predetermined target level (e.g., baseline minus 0.28 mmol/L or 5 mg/dL) [23].

- Frequent Blood Sampling: Blood glucose is measured frequently (e.g., every 5-10 minutes initially, then at longer intervals) for a defined period, typically 24 hours.

- Real-Time Adjustment: The glucose infusion rate (GIR) is adjusted in real-time based on the frequent glucose measurements to maintain euglycemia.

- C-Peptide Monitoring: Serum C-peptide levels are periodically measured to confirm the suppression of endogenous insulin secretion, ensuring that the observed glucose-lowering effect is solely from the exogenous insulin.

- Key Output: The primary outcome is the Glucose Infusion Rate (GIR) over time. The area under the GIR curve (GIRAUC) and the maximum GIR (GIRmax) are critical PD parameters for comparing insulin formulations [23].

Pharmacokinetic (PK) Blood Sampling and Analysis

Concurrent PK profiling is essential to link the observed pharmacodynamic effect to the systemic concentration of the insulin analogue.

- Objective: To measure the plasma concentration of the insulin analogue over time following subcutaneous administration.

- Detailed Workflow [23]:

- Blood Collection: Serial blood samples are collected at predetermined time points (e.g., pre-dose, 10, 20, 30, 40, 60, 90, 120, 150, 180, 240, 300, 360, 480, 600, 720, 840, 960, 1200, and 1440 minutes post-dose).

- Sample Processing: Plasma is separated from blood cells via centrifugation.

- Analytical Method: The concentration of the specific insulin analogue is quantified using highly specific methods such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with Mass Spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) [23]. This technique is necessary to distinguish the analogue from endogenous insulin and its metabolites.

- Key Output: The primary PK parameters are the maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), the time to Cmax (Tmax), and the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC). These parameters define the absorption and exposure profile of the insulin [23].

The workflow for a comprehensive PK/PD study integrating these protocols is depicted below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Insulin Pharmacology Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example from Search Results |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Insulin Analogues | The test articles for pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic comparison. | Insulin glargine, detemir, degludec, lispro, aspart [16] [20]. |

| HPLC-MS/MS System | The analytical platform for specific and sensitive quantification of insulin analogue concentrations in biological samples (plasma) [23]. | ACQUITY UPLC Protein BEH C4 Column coupled with a Triple Quad 6500+ Mass Spectrometer [23]. |

| Glucose Analyzer | To provide rapid and accurate blood glucose measurements essential for real-time adjustment of the glucose infusion during a euglycemic clamp. | Device using the glucose oxidase method [23]. |

| C-Peptide ELISA Kit | To measure serum C-peptide levels, confirming suppression of endogenous insulin secretion during clamp studies [23]. | Not specified by brand, but methodology is standard [23]. |

| Variable-Infusion Pump | To administer the 20% glucose solution at a precisely controlled and adjustable rate during the euglycemic clamp procedure [23]. | Not specified by brand, but essential for the procedure. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Insulin Internal Standards | Used in HPLC-MS/MS analysis to correct for sample matrix effects and improve quantitative accuracy. | Implied by the use of MS for bioanalysis, though not explicitly stated [23]. |

The development of long-acting insulin analogues through mechanisms of albumin binding, precipitation via isoelectric point shift, and multi-hexamer formation represents a triumph of rational drug design. Each strategy offers distinct molecular approaches to achieving a stable, protracted, and predictable basal insulin supply, closely mimicking physiological secretion. The euglycemic clamp technique, coupled with sophisticated analytical methods like HPLC-MS/MS, provides the critical experimental foundation for comparing these analogues. As research progresses, new mechanisms and ultra-long-acting formulations like once-weekly insulins continue to push the boundaries, promising even better tools for managing diabetes. For researchers, a deep understanding of these principles and methodologies is essential for driving the next wave of innovation in insulin therapeutics.

The development of ultra-long-acting insulin analogs represents a frontier in diabetes management, aiming to reduce injection frequency from daily to weekly administrations. A critical challenge in achieving this goal lies in overcoming the inherent thermodynamic instability of the native insulin molecule, which is susceptible to a previously overlooked clearance mechanism: redox-mediated disulfide bond cleavage [24] [25]. This process, insignificant for rapid-clearing native insulin, becomes a major determinant of the pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) profiles of analogs with prolonged circulation times. This guide provides a comparative analysis of how structural engineering, particularly in insulin icodec, mitigates this clearance pathway to enable a once-weekly dosing regimen, and outlines the essential experimental protocols for evaluating these properties in novel analogs.

Redox-Mediated Clearance: A Central Mechanism

The Redox Clearance Pathway

Native insulin is a heterodimeric protein comprising A and B chains linked by two disulfide bonds (B7-A7 and B19-A20) and one intra-chain bond (A6-A11) [25]. In the redox environment of plasma, these disulfide bonds, particularly the solvent-exposed A7-B7 bridge, are vulnerable to attack by small-molecule thiols like glutathione and cysteine [24] [25]. This thiol-disulfide exchange reaction can lead to the splitting of the insulin molecule into its separate A and B chains.

- Irreversible Inactivation: The separated chains are hormonally inactive. Given the low circulating concentrations of injected insulin, the reverse reaction is kinetically infeasible, making chain separation an irreversible inactivation and clearance pathway [24].

- Kinetic Trapping of Native Insulin: The rapid receptor-mediated clearance of native insulin (half-life of 4-6 minutes) means it is cleared from circulation before redox cleavage becomes significant [24] [16]. Ultra-long-acting analogs, by design, circulate for much longer periods (days to weeks), thus becoming highly susceptible to this degradation mechanism [25].

Table 1: Key Features of Redox-Mediated Insulin Clearance

| Feature | Description | Implication for Ultra-Long-Acting Analogs |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Process | Thiol-disulfide exchange with plasma thiols (e.g., glutathione) [25] | A major non-receptor-mediated clearance pathway for analogs with long half-lives. |

| Resulting Products | Separated, cyclic A-chain and B-chain [24] [25] | Irreversible loss of hormonal activity and potency. |

| Dependence on Half-life | Significance increases with longer circulation time [25] | Must be addressed through molecular design to achieve once-weekly dosing. |

| Visualization of Pathway | The diagram below illustrates the redox-mediated cleavage process. |

Comparative Analysis of Insulin Analogs

Molecular Design Strategies for Stability

The molecular engineering of ultra-long-acting insulin analogs focuses on two primary strategies: enhancing albumin binding to create a circulating depot and increasing intrinsic structural stability to resist degradation.

- Albumin Binding: Fatty acid acylation (e.g., a C20 fatty diacid in icodec) promotes strong, reversible binding to human serum albumin (HSA). This binding shields the insulin molecule from receptor-mediated clearance and delays renal clearance, thereby prolonging its half-life [24] [26] [16].

- Amino Acid Substitutions for Stability: Key amino acid substitutions are introduced to increase the thermodynamic stability of the insulin monomer, reducing its flexibility and the solvent accessibility of its disulfide bonds, thereby directly countering redox-mediated cleavage [25].

Table 2: Comparative Structural Modifications of Long-Acting Insulins

| Insulin Analog | Dosing Frequency | Key Albumin-Binding Moieties | Key Stabilizing Amino Acid Substitutions | Primary Mechanism of Protraction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin Detemir | Once- or twice-daily | C14 fatty acid chain (myristic acid) at LysB29 [16] | None | Albumin binding, increased self-association [16] |

| Insulin Degludec | Once-daily | C16 fatty diacid chain (hexadecandioic acid) at LysB29 [16] | Removal of ThrB30 [16] | Multi-hexamer formation at injection site, albumin binding [16] |

| Insulin Icodec | Once-weekly | C20 fatty diacid with linker (gGlu-2OEG) at LysB29 [25] [26] | A14E, B16H, B25H [24] [25] | Strong albumin binding, reduced receptor affinity, enhanced disulfide stability [24] |

| Novel Analog (TBE001-A-S033) | Once-weekly (preclinical) | C22 fatty diacid with modified linker/spacer [26] | A14E, B16H, B25H (icodec backbone) [26] | Optimized albumin binding and stability [26] |

Quantitative Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Comparison

The structural modifications in insulin icodec translate into a significantly extended half-life, enabling once-weekly dosing. Clinical and modeling studies have confirmed its efficacy and safety profile in comparison to daily basal insulins.

- Half-life and Dosing: Insulin icodec has a half-life of approximately 196 hours (about 8 days) in humans, which is the foundation for its once-weekly administration [25]. A PK/PD modeling analysis of phase 3 trials (ONWARDS 2 and 4) confirmed that switching from daily basal insulin to icodec provides sustained glycemic control over 26 weeks without an increased rate of hypoglycemia [27].

- In Vitro Stability Data: The enhanced stability of icodec is quantifiable. In a redox stability assay, the combination of A14E, B16H, and B25H substitutions in the icodec backbone conferred significantly greater resistance to reductive cleavage compared to human insulin [25]. This was correlated with an increased midpoint of unfolding in chemical denaturation assays, indicating higher thermodynamic stability [25].

Table 3: Experimental Pharmacokinetic and Stability Data

| Parameter | Human Insulin | Insulin Icodec | Experimental Analog TBE001-A-S033 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma Half-life | 4-6 minutes [16] | ~196 hours [25] | Slightly shorter than icodec in Beagle dogs [26] |

| Dosing Frequency | Multiple daily | Once-weekly [25] | Once-weekly (target, preclinical) [26] |

| GuHCl Unfolding Midpoint (Δ Stability) | 4.50 M [25] | 5.42 M [25] | Data not provided in search results |

| HSA Binding Affinity | Very low | High (via C20 diacid) [24] | Higher than icodec (via C22 diacid) [26] |

Experimental Protocols for Evaluation

Assessing Redox Stability

Objective: To evaluate the susceptibility of an insulin analog to thiol-disulfide exchange-mediated chain separation [25].

Protocol:

- Preparation: Incubate the insulin analog in a buffer system with a defined redox potential, typically using a gradient of reducing agents like glutathione or dithiothreitol (DTT).

- Analysis: Use reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) to separate and quantify the intact insulin molecule and its degradation products over time.

- Identification: Confirm the identity of the degradation peaks as the separated A-chain and B-chain using mass spectrometry. The B-chain appears as a single peak, while the A-chain may present three isoforms due to disulfide bond isomerization [25].

- Quantification: The stability of the analog is expressed as the rate of degradation or the relative amount of intact insulin remaining after a fixed incubation period compared to a control (e.g., human insulin).

Measuring Thermodynamic Stability

Objective: To determine the thermodynamic folding stability of the insulin monomeric analog [25].

Protocol:

- Denaturation: Subject the insulin analog to increasing concentrations of a chemical denaturant, such as guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl).

- Signal Monitoring: Monitor the unfolding process using far-UV circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy, which detects changes in the protein's secondary structure.

- Data Fitting: Plot the CD signal as a function of denaturant concentration and fit the data to a unfolding model to calculate the midpoint of the transition (the [GuHCl]1/2 at which 50% of the molecules are unfolded).

- Interpretation: A higher [GuHCl]1/2 value indicates a more thermodynamically stable protein structure, which correlates with resistance to redox-mediated cleavage [25].

Determining Albumin Binding Affinity

Objective: To quantify the binding affinity of an insulin analog to Human Serum Albumin (HSA), a key driver of prolonged half-life.

Protocol:

- Immobilization: Immobilize HSA on a biosensor chip (e.g., for Surface Plasmon Resonance) or in a plate-based assay.

- Binding Kinetics: Expose the immobilized HSA to a range of concentrations of the insulin analog.

- Measurement: Measure the binding response in real-time to determine the association rate (kon) and dissociation rate (koff). The equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) is calculated as koff/k_on.

- Comparison: A lower K_D value signifies a higher binding affinity for HSA. This assay is crucial for screening novel fatty acid side chains, as demonstrated in the development of TBE001-A-S033 [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Studying Insulin Stability and Clearance

| Research Reagent / Method | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Glutathione (Reduced/Oxided) | Creates a physiologically relevant redox environment to challenge insulin disulfide bonds in stability assays [25]. |

| Guanidine Hydrochloride (GuHCl) | A chemical denaturant used to unfold insulin in a controlled manner to measure its thermodynamic stability [25]. |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectrophotometer | Measures changes in the secondary structure of insulin during unfolding induced by denaturants [25]. |

| RP-HPLC with Mass Spectrometry | Separates, detects, and identifies intact insulin and its degradation products (A-chain, B-chain) with high resolution and accuracy [25]. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | A label-free technique for real-time analysis of the binding kinetics and affinity between insulin analogs and HSA [26]. |

| Human Serum Albumin (HSA) | The key plasma protein used in experiments to evaluate the albumin-binding capacity of long-acting insulin analogs [26]. |

The paradigm for developing ultra-long-acting insulin analogs has fundamentally shifted with the recognition of redox-mediated clearance as a critical factor. The success of once-weekly insulin icodec demonstrates that a dual-strategy approach—combining strong albumin binding with enhanced intrinsic stability through specific amino acid substitutions (A14E, B16H, B25H)—is effective in mitigating this pathway. Future innovations, such as single-chain insulin designs [24] or diselenide bridge substitutions [24], may further push the boundaries of stability and safety. For researchers, a standardized experimental workflow assessing redox stability, thermodynamic folding, and HSA binding is indispensable for the rational design and evaluation of the next generation of ultra-long-acting therapeutic proteins.

Quantifying Action and Efficacy: Advanced PK/PD Modeling and Clamp Methodologies

The hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp (HEC) technique, developed in 1979, remains the undisputed gold standard for the in vivo assessment of insulin sensitivity and the pharmacodynamic (PD) properties of insulin formulations [28] [29]. This method provides a direct and quantitative measure of whole-body glucose disposal under standardized conditions, offering precision and accuracy unmatched by other techniques [28]. For researchers and pharmaceutical developers evaluating new insulin analogs or biosimilars, the clamp technique provides critical pharmacokinetic (PK) and PD data required by regulatory agencies for market approval [30] [31].

This objective comparison examines the performance of the euglycemic clamp against alternative methods and details its central role in advancing insulin pharmacotherapy. By synthesizing evidence from recent clinical trials and methodological studies, this guide serves as a comprehensive resource for scientists designing metabolic research or drug development programs.

Core Principle and Comparative Advantage

Fundamental Mechanism

The foundational principle of the HEC is to create an artificial steady state where plasma glucose is "clamped" at a predetermined target level (typically euglycemia) through a variable glucose infusion, while insulin is infused at a constant rate to achieve hyperinsulinemia [28]. During this procedure, the Glucose Infusion Rate (GIR) required to maintain euglycemia serves as the direct quantitative measure of insulin action—higher GIR values indicate greater insulin sensitivity [28] [32]. Since endogenous glucose production is largely suppressed under hyperinsulinemic conditions, the exogenous GIR essentially equals the total rate of glucose disposal by body tissues [28].

Advantages Over Alternative Methods

The table below compares the euglycemic clamp technique with other common methods for assessing insulin sensitivity.

Table 1: Comparison of Insulin Sensitivity Assessment Methods

| Method | Principle | Key Metrics | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euglycemic Clamp [28] | Variable glucose infusion maintains basal glucose during fixed insulin infusion. | Glucose Infusion Rate (GIR), M-value. | Gold standard; direct quantitative measure; can be combined with tracers and imaging. | Labor-intensive, complex, requires specialized equipment and personnel. |

| Frequently Sampled Intravenous Glucose Tolerance Test (FSIVGTT) [28] | Model-based analysis of glucose and insulin dynamics after IV glucose bolus. | Insulin Sensitivity Index (SI). | Less labor-intensive than clamp; provides data on insulin secretion. | Does not provide a steady state; less suitable for combination with other metabolic techniques. |

| Homeostasis Model Assessment (HOMA-IR) [28] | Mathematical model based on fasting glucose and insulin levels. | HOMA-IR score. | Simple, inexpensive, suitable for large-scale epidemiological studies. | High variability, theoretically limited to the fasting state, not reliable in diabetes. |

| Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM)-Derived Indices [33] | Statistical analysis of glucose time-series under physiological conditions. | ACVar, CGMStd. | Captures dynamic glucose regulation in free-living conditions; less invasive. | Indirect measure; validation against clamp required; performance in diabetic populations under investigation. |

The clamp's primary advantage is its ability to directly quantify insulin-mediated glucose disposal under controlled steady-state conditions, thereby eliminating the confounding effects of counter-regulatory hormone responses that plague other methods [28]. Furthermore, its versatility allows for combination with tracer methodologies, indirect calorimetry, and imaging techniques to dissect tissue-specific metabolic fluxes [28] [34].

Applications in Insulin Analog Development

The euglycemic clamp is indispensable for establishing bioequivalence between insulin formulations and characterizing the PK/PD profiles of new analogs. The following table summarizes key findings from recent clamp studies.

Table 2: Recent Euglycemic Clamp Studies in Insulin Analog Development

| Study Focus | Insulin Type & Dose | Clamp Duration & Design | Key PK/PD Findings (GMR, 90% CI) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biosimilar Ultra-Rapid Lispro [31] | Ultra-rapid lispro in healthy volunteers. | 8-hour, double-blind, randomized, crossover clamp. | PK (AUC, Cmax) and PD profiles comparable; GMRs within 80-125%. | [31] |

| Biosimilar Insulin Glargine [35] | Insulin glargine (0.4 IU/kg) in healthy male volunteers. | 24-hour, randomized, open-label, crossover clamp. | GIR~max~: 42.75 (T) vs 45.28 (R) mg·kg⁻¹·min⁻¹. Bioequivalence demonstrated. | [35] |

| Biosimilar Premixed Lispro 25 [3] | Premixed insulin lispro (0.3 IU/kg) in healthy male volunteers. | 24-hour, randomized, open-label, crossover clamp. | GIR~max~: 4.47 (T) vs 4.12 (R) mg·kg⁻¹·min⁻¹. 90% CIs for PK/PD within bioequivalence range. | [3] |

| Long-Acting Insulin Degludec [32] | Insulin degludec (0.4 IU/kg) in healthy volunteers. | 24-hour clamp assessing test quality. | Established CV~BG~ ≤ 3.5% and C-peptide reduction ≥ 50% as key quality indicators. | [32] |

These studies consistently demonstrate the clamp technique's precision in detecting subtle differences in insulin onset, peak action, and duration. The robust PK/PD data generated underpin regulatory approvals for biosimilar and novel insulin products, ensuring their clinical performance matches reference products.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Standardized Clamp Procedure

A typical HEC procedure for evaluating insulin preparations involves the following key steps, which can be adapted for specific study objectives and populations:

- Participant Preparation: After an overnight fast (>10 hours), participants rest in a supine position. Catheters are placed in a forearm vein for glucose/insulin infusion and in the contralateral arm (with a heating pad for arterialized venous blood) for frequent blood sampling [34] [32] [35].

- Baseline Period: Blood glucose (BG) is measured multiple times (e.g., at -30, -20, and -10 minutes) to establish a stable fasting baseline level [32] [35].

- Insulin Administration & Glucose Clamping:

- A subcutaneous injection of the test or reference insulin preparation is administered [3] [35].

- The target BG is typically set slightly below the baseline (e.g., baseline minus 0.3 mmol/L or 5%) to help suppress endogenous insulin secretion [30] [32].

- A variable 20% glucose solution is infused, and the GIR is adjusted based on frequent (e.g., every 5-10 minutes) BG measurements to maintain the BG at the target level [32] [3]. The entire process is often automated using systems like ClampArt for enhanced precision [29].

- Blood Sampling: Blood is collected at predefined intervals for PK analysis (measurement of plasma insulin concentration) and for monitoring C-peptide levels to confirm suppression of endogenous insulin secretion [32] [3].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the sequential flow and key decision points in a standard euglycemic clamp procedure.

Quality Control and Standardization

High-quality clamp data requires strict adherence to standardized protocols and rigorous quality control. Key performance indicators include:

- Blood Glucose Variability: The Coefficient of Variation of Blood Glucose (CV~BG~) is a primary metric. A CV~BG~ ≤ 3.5% is indicative of a high-quality clamp for long-acting insulin studies, ensuring stable experimental conditions [32].

- Endogenous Insulin Suppression: Effective suppression of the pancreas's own insulin secretion is confirmed by a reduction in C-peptide levels. A reduction of ≥ 50% from baseline is generally considered sufficient to exclude confounding effects from endogenous insulin [32].

- Additional Metrics: Other useful quality indices include the percentage of time BG is within the target range, the mean excursion from target BG, and the area under the curve of glucose excursion [32].

Advanced Research Applications

Tissue-Specific Insulin Sensitivity

The standard HEC measures whole-body insulin sensitivity. However, when combined with dynamic imaging techniques like [18F]FDG-PET/MRI, the method can quantify glucose uptake into specific tissues such as skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, and the brain [34]. This approach has revealed that individuals with Type 2 Diabetes (T2DM) exhibit impaired glucose uptake specifically in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue under insulin stimulation, highlighting the technique's power to elucidate tissue-level pathophysiology [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Equipment for Euglycemic Clamp Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Insulin Formulation [31] [35] | The drug substance under investigation (prandial or basal). | Recombinant human insulin or analogs (e.g., Lispro, Glargine, Degludec). |

| 20% Glucose Solution [32] [35] | Variable infusion to maintain target blood glucose level. | Sterile, pharmaceutical grade for intravenous administration. |

| C-Peptide Assay [30] [32] | Monitor suppression of endogenous insulin secretion. | Validated ELISA or chemiluminescent immunoassay. |

| Glucose Analyzer [34] [32] | Rapid and accurate bedside measurement of blood glucose. | Glucose oxidase method (e.g., HemoCue, BIOSEN C_Line). |

| Automated Clamp System [29] | Integrates continuous glucose sensing and algorithm-driven glucose infusion. | CE-certified systems like ClampArt or Biostator. |

| Validated Bioanalytical Method [3] [35] | Quantify plasma concentrations of the insulin analog. | HPLC-MS/MS or specific immunoassays. |

| Indirect Calorimetry [28] [29] | Assess substrate utilization (glucose/lipid oxidation). | Metabolic cart for measuring O₂ consumption and CO₂ production. |

| Stable Isotope Tracers [29] | Measure endogenous glucose production and lipolysis. | [6,6-²H₂]-glucose, [¹³C]-oleate. |

The hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp technique remains an indispensable tool in metabolic research and drug development. Its status as the gold standard is upheld by its direct quantitative nature, versatility, and unparalleled accuracy in characterizing the pharmacodynamic properties of insulin formulations. While emerging technologies like CGM offer promising, less invasive alternatives for population screening, the clamp is unlikely to be replaced for definitive proof-of-mechanism studies and regulatory submissions of new insulin products. Ongoing refinements in automation and standardization, as evidenced by recent studies, continue to enhance its precision and reliability, ensuring its central role in advancing the understanding and treatment of diabetes.

Mechanism-based pharmacodynamic (PD) modeling represents a quantitative discipline that integrates pharmacokinetics (PK), pharmacological systems, and pathophysiological processes to understand the intensity and time-course of drug effects on the body [36]. Unlike classical empirical approaches, mechanism-based models seek to separate drug-specific parameters from system-specific parameters, creating a platform that is more readily translatable across different experimental conditions and patient populations [36] [37]. The core value of these models lies in their ability to quantify and predict drug-system interactions for both therapeutic and adverse drug responses, thereby playing a critical role in drug discovery, development, and pharmacotherapy [36].

In the context of insulin therapy, mechanism-based PK/PD modeling has become indispensable. The goal of insulin therapy in patients with either type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) or type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is to match as closely as possible normal physiologic insulin secretion to control fasting and postprandial plasma glucose [21]. The development of various insulin analogs with modified molecular structures has created a landscape where modeling can objectively compare their performance, guide formulation design, and optimize dosing regimens [21] [37]. This review will explore how different PK/PD modeling approaches—specifically integrating absorption, biophase, and indirect response models—provide a framework for comparing the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles of insulin analogs.

Theoretical Framework of Key PK/PD Models

Simple Direct Effect and Absorption Models

The most fundamental relationship in pharmacodynamics is described by the Hill equation (or Emax model), which assumes drug effects are directly proportional to receptor occupancy and that plasma drug concentrations are in rapid equilibrium with the effect site [36]:

This equation characterizes the concentration-effect relationship through a baseline effect (E₀), the maximum possible effect (E_max), and the drug concentration producing half maximal effect (EC₅₀) [36]. For drug administration via extravascular routes, absorption to the central compartment is typically described by either first-order or zero-order processes [37]. A one-compartment model with first-order absorption and elimination can be described by the following differential equations [37]:

Where A₁ represents the mass of drug at the administration site, ka is the absorption rate constant, A₂ denotes the mass of drug in the body, CL represents clearance, V represents volume of distribution, and Cp denotes plasma drug concentration [37].

Biophase Distribution Model

Often, a temporal disconnect exists between plasma drug concentrations and pharmacological effects, resulting in a hysteresis loop when plotting effect versus concentration [36]. Distribution to the site of action—the "biophase"—can represent a rate-limiting process accounting for this delay. The biophase model introduces a hypothetical effect compartment linked to the central compartment, with the rate of change of drug concentrations at the biophase (C_e) defined as [36]:

Where k_eo represents the equilibration rate constant between plasma and effect compartment [36]. This model effectively collapses the hysteresis loop, allowing characterization of the direct concentration-effect relationship.

Indirect Response Models

Many drug effects occur through indirect mechanisms where the drug stimulates or inhibits the production or loss of endogenous substances or mediators that subsequently drive the observed response [36]. Indirect response models capture these complex temporal dynamics by modeling the turnover of these response biomarkers, which often provides a more mechanistic representation of the drug's pharmacodynamic action compared to direct effect models.

Comparative PK/PD Analysis of Insulin Analogs

Rapid-Acting Insulin Analogs

Rapid-acting insulin analogs (aspart, lispro, glulisine) were designed to mimic the physiological first-phase insulin release in response to meals [21] [9]. Structural modifications, such as the paired amino acid substitution of proline and lysine at positions B28 and B29 in insulin lispro, reduce self-assembly tendencies, leading to faster absorption and shorter duration of action compared to regular human insulin [9].

Table 1: Pharmacokinetic Properties of Rapid-Acting Insulin Analogs

| Insulin Analog | Structural Modifications | Onset (minutes) | Peak (minutes) | Duration (hours) | T_max (minutes) | C_max (mU/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lispro [21] [9] | B28Pro→Lys, B29Lys→Pro | 5-15 | 30-60 | 3-4 | 30-90 | 116 |

| Aspart [21] | B28Pro→Asp | 10-20 | 40-50 | 3-5 | 40-50 | 82.1 |

| Glulisine [21] [9] | B3Lys→Glu, B29Lys→Glu | 20 | 60 | 4 | 30-90 | 82 |

| Regular Human Insulin [21] | - | 30 | 60-120 | 6-8 | 50-120 | 51 |

Long-Acting Insulin Analogs

Long-acting insulin analogs (glargine, detemir, degludec) provide basal insulin coverage with flatter time-action profiles and reduced peak-trough fluctuations compared to NPH insulin [21] [9]. These analogs employ different strategies to prolong their duration, including shifting the isoelectric point (glargine) or enhancing albumin binding (detemir, degludec) [9].

Table 2: Pharmacokinetic Properties of Long-Acting Insulin Analogs

| Insulin Analog | Structural Modifications | Mechanism of Prolongation | Onset (hours) | Peak | Duration (hours) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glargine [21] [9] | A21Gly→Arg, B31Arg, B32Arg | Isoelectric point shift → precipitation at neutral pH | 1-2 | Flat | ~24 |

| Detemir [21] [9] | B30Thr deletion, B29Lys→myristic acid | Albumin binding via fatty acid acylation | 1.6 | Flat | Up to 24 |

| Degludec [9] | B30Thr deletion, B29Lys→hexadecandioic acid | Multi-hexamer formation & albumin binding | - | Flat | >24 |

| NPH Insulin [21] | Protamine complexation | Crystal formation | 1-2 | 3-8 hours | 12-15 |

Emerging Once-Weekly Insulin Analogs