High-Protein Diets for Glucose Control: Mechanisms, Efficacy, and Clinical Applications in Diabetes Management

This article systematically examines the efficacy of high-protein diets (HPDs) for glycemic control, addressing the needs of researchers and drug development professionals.

High-Protein Diets for Glucose Control: Mechanisms, Efficacy, and Clinical Applications in Diabetes Management

Abstract

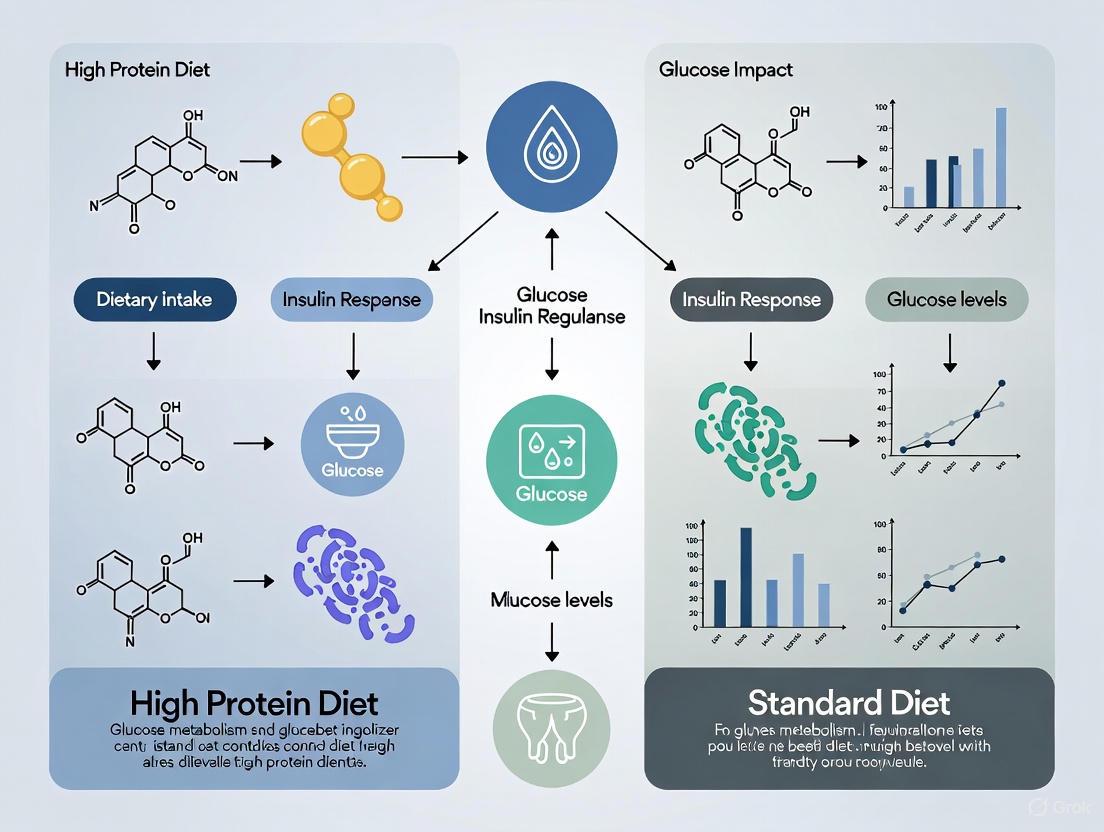

This article systematically examines the efficacy of high-protein diets (HPDs) for glycemic control, addressing the needs of researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational physiological mechanisms by which dietary proteins and amino acids modulate insulin secretion and glucose homeostasis. The analysis covers methodological approaches for implementing HPDs in clinical settings and specialized nutritional formulations, including their effects on postprandial glucose, insulin resistance, and body composition. We troubleshoot implementation challenges, including variability in protein sources, long-term sustainability, and safety considerations. Finally, we provide comparative validation against other dietary interventions, such as low-carbohydrate diets, and discuss implications for future therapeutic development and personalized nutrition strategies for diabetes management.

Molecular Mechanisms: How Dietary Proteins Regulate Glucose Homeostasis and Insulin Signaling

Insulinotropic Effects of Amino Acids: Direct Pancreatic β-Cell Stimulation Pathways

The management of blood glucose is a central tenet of metabolic health, with pancreatic β-cell insulin secretion playing the pivotal role. While glucose is the primary stimulus for insulin release, the contribution of amino acids to this process is significant and complex. Understanding the direct pathways through which amino acids stimulate pancreatic β-cells is not only a matter of fundamental physiology but also critically informs the ongoing debate regarding the efficacy of high-protein diets (HPD) versus standard diets for glucose control. This review objectively compares the direct insulinotropic mechanisms of amino acids, framing them within the broader context of dietary protein research. We synthesize experimental data from key studies, detail the methodologies used to acquire them, and visualize the core signaling pathways, providing a resource for therapeutic development.

Mechanisms of Amino Acid-Stimulated Insulin Secretion (AASIS)

Amino acids stimulate insulin secretion through distinct and complementary mechanisms, primarily functioning as metabolic fuels to generate ATP or as signaling molecules that amplify secretion. The following pathway diagram synthesizes these core mechanisms, showing how different amino acids are sensed to ultimately trigger insulin exocytosis.

Diagram 1: Integrated pathways of amino acid-stimulated insulin secretion. The map shows three primary modes of action: the triggering pathway (blue) where amino acid oxidation elevates the ATP/ADP ratio; the signaling amplification pathway (green) where amino acids potentiate secretion; and the mTORC1 feedback pathway (red) that intrinsically limits excessive insulin release via actin remodeling.

The core mechanisms illustrated above are further elucidated by specific disease models, particularly congenital hyperinsulinism (HI), which provide powerful insights into the regulation of AASIS. The following table systematically compares the mechanisms and key experimental findings across three such models.

Table 1: Mechanisms of Amino Acid-Stimulated Insulin Secretion in Congenital Hyperinsulinism (HI) Models

| HI Model | Genetic Defect | Primary Mechanism of AASIS | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDH-HI [1] | Gain-of-function mutation in Glutamate Dehydrogenase (GDH) | Increased amino acid oxidation → ↑ ATP production → KATP channel closure and cell depolarization [1]. | Transgenic (H454Y) islets showed hypersensitivity to glutamine and leucine; increased GDH flux and ammonia production; EGCG inhibited GDH and blocked hypoglycemia [1]. |

| KATP-HI [1] | Loss-of-function in ATP-dependent K+ channel (KATP) | Constitutive membrane depolarization; amino acids provide amplifying signals independent of KATP closure [1]. | Insulin secretion is decoupled from metabolic regulation; amino acids directly augment calcium-triggered exocytosis [1]. |

| SCHAD-HI [1] | Short-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency | Loss of GDH inhibition → Increased GDH flux and amino acid oxidation, mimicking GDH-HI [1]. | SCHAD protein binds to and inhibits GDH; knockout mice showed increased GDH activity and leucine-stimulated insulin secretion [1]. |

Furthermore, the nutrient sensor mTORC1 has been identified as a critical intrinsic feedback regulator. Activated by glucose via the insulin secretion machinery, mTORC1 constrains insulin exocytosis, particularly the second phase, by promoting RhoA-dependent F-actin polymerization, which limits vesicle movement [2]. This mechanism prevents excessive insulin release and maintains metabolic balance.

Quantitative Data from Human and Animal Studies

The physiological mechanisms of AASIS translate into significant functional outcomes, which have been quantified in various experimental systems. The following table consolidates key quantitative findings from pivotal studies on amino acid and high-protein diet effects.

Table 2: Quantitative Summary of Amino Acid and High-Protein Diet Effects on Insulin Secretion and Metabolic Parameters

| Study System / Intervention | Key Metabolic Outcome | Quantified Change | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDH-TG Mouse Islets (AASIS) | Insulin secretion response to glutamine | Responsive to glutamine alone (control islets unresponsive) [1]. | [1] |

| GDH-TG Mouse Islets (AASIS) | GDH flux with [2-¹⁵N]glutamine | ~3-fold stimulation of flux vs. control [1]. | [1] |

| Obese Humans (T2D)52-week HP Diet | Weight Loss | -10.2 ± 1.6 kg (HP) vs -12.7 ± 4.8 kg (NP); p=0.336 [3]. | [3] |

| Obese Humans (T2D)52-week HP Diet | HbA1c, insulin, triglycerides | Significant improvement with weight loss, no difference between HP and NP diets [3]. | [3] |

| Obese Prediabetic Humans6-month HP Diet | Remission of prediabetes | 100% remission in HP group (0% in HC group) [4]. | [4] |

| Obese Prediabetic Humans6-month HP Diet | GLP-1 and GIP response | Greater increase in GLP-1 and GIP with HP vs HC diet [4]. | [4] |

| Obese Women (No Diabetes)6-month HP Diet | Insulin sensitivity and β-cell function | Insulin sensitivity: +4 vs +0.9 (HC); β-cell function: +7.4 vs +2.1 (HC) [5]. | [5] |

| Humans with T2D5-week HP Diet | 24-hour integrated glucose area | 40% decrease with HP diet vs control diet [6]. | [6] |

| Humans with T2D5-week HP Diet | Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) | Decreased 0.8% (HP) vs 0.3% (control); p < 0.05 [6]. | [6] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key AASIS Models

To enable replication and critical evaluation, this section outlines the core methodologies used in the studies cited to investigate AASIS.

- Objective: To measure real-time, dynamic insulin secretion from isolated pancreatic islets in response to specific amino acid challenges.

- Procedure:

- Islet Isolation: Pancreatic islets are isolated from model animals (e.g., wild-type or transgenic mice) via collagenase digestion and density gradient centrifugation.

- Perifusion System: A batch of size-matched islets is loaded into a chamber maintained at 37°C.

- Buffer Perifusion: A basal buffer (e.g., containing 2.8 mM glucose) is continuously perfused through the chamber to establish a stable baseline.

- Stimulus Application: The perfusate is switched to a test buffer containing a specific amino acid (e.g., 10 mM glutamine, a leucine mixture) or a combination of nutrients.

- Sample Collection: Effluent from the chamber is collected at frequent intervals (e.g., every 2-5 minutes) into tubes.

- Insulin Assay: The insulin concentration in each collected fraction is quantified by radioimmunoassay (RIA) or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

- Key Measurements: The insulin secretion rate over time, allowing for the distinction between first-phase and second-phase secretion in response to the stimulus.

- Objective: To quantitatively measure the flux of amino acids through specific metabolic pathways, such as the GDH reaction, in isolated islets.

- Procedure:

- Islet Incubation: Isolated islets are incubated in media containing a stable isotope-labeled substrate (e.g., [2-¹⁵N]glutamine).

- Metabolite Extraction: At designated time points, islets are rapidly harvested and metabolites are extracted.

- Metabolomic Analysis: The extracts are analyzed using techniques like gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC-MS).

- Flux Calculation: The transfer of the ¹⁵N label from [2-¹⁵N]glutamine to [2-¹⁵N]glutamate and subsequently to [¹⁵N]ammonia is tracked. The specific flux via the GDH reaction is calculated based on the enrichment of the products.

- Key Measurements: Metabolic flux rates (e.g., GDH flux), production of specific metabolites (e.g., ammonia, α-ketoglutarate), and the ATP/ADP ratio.

- Objective: To compare the long-term effects of a high-protein (HP) diet versus a high-carbohydrate (HC) or normal-protein (NP) diet on weight loss, body composition, and glucose control in human subjects.

- Protocol:

- Participant Recruitment: Enrollment of adults with obesity, often with prediabetes or type 2 diabetes, who are weight-stable.

- Randomization: Participants are randomly assigned to either the HP or control diet group.

- Dietary Intervention: The intervention period typically lasts from 6 months to 1 year.

- HP Diet: ~25-30% protein, ~30% fat, ~40% carbohydrate.

- Control Diet: ~15-21% protein, ~30% fat, ~53-55% carbohydrate.

- Both diets are energy-restricted (e.g., -500 kcal/day).

- Outcome Measurements:

- Anthropometrics: Body weight, BMI, body composition (via DXA scan).

- Glycemic Control: Fasting glucose and insulin, HbA1c, Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT).

- Hormonal Response: Plasma levels of insulin, C-peptide, GLP-1, GIP, ghrelin.

- Cardiometabolic Markers: Lipid profile, blood pressure, oxidative stress markers.

- Key Measurements: Changes from baseline to endpoint within and between diet groups for all outcome variables.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Research into AASIS relies on a specific set of reagents, inhibitors, and model systems. The following table details key tools used in the featured experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Amino Acid-Stimulated Insulin Secretion

| Reagent / Model | Function/Description | Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|

| Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG) | Natural polyphenol that inhibits GDH by binding to its ADP-activation site [1]. | Used to probe GDH function; shown to block glutamine-stimulated insulin secretion in GDH-HI islets and prevent amino acid-induced hypoglycemia in vivo [1]. |

| GDH-HI Transgenic Mouse | Animal model expressing a gain-of-function mutation (e.g., H454Y) in the GDH enzyme under an insulin promoter [1]. | Used to study the mechanisms of protein-sensitive hypoglycemia and test potential therapeutics like EGCG [1]. |

| Diazoxide | KATP channel agonist that keeps the channel open, preventing membrane depolarization. | Used to dissect KATP-dependent and -independent pathways of insulin secretion [1]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Amino Acids (e.g., [2-¹⁵N]Glutamine) | Amino acids with heavy isotopes (e.g., ¹⁵N) incorporated, allowing tracking of metabolic fate. | Essential for using GC-MS to quantify metabolic flux through specific pathways like the GDH reaction [1]. |

| Rapamycin | Specific allosteric inhibitor of the mTORC1 complex. | Used to investigate the role of mTORC1 in the feedback regulation of insulin secretion [2]. |

| Perifusion System | An ex vivo setup that allows continuous, real-time monitoring of hormone secretion from cultured tissues. | Superior to static incubation for characterizing the dynamic kinetics (phasic release) of insulin secretion from isolated islets [1]. |

The direct stimulation of pancreatic β-cells by amino acids is a multifaceted process involving distinct triggering and amplifying pathways, elegantly revealed by disease models like GDH-HI and SCHAD-HI. The intrinsic feedback mechanism mediated by mTORC1 further adds a layer of sophistication, ensuring that insulin release is precisely calibrated [2] [1]. When these molecular insights are viewed in the context of clinical dietary studies, a nuanced picture emerges. While the weight loss achieved through caloric restriction remains the dominant factor for improving glucose control [3], high-protein diets exert significant direct effects on β-cell function and incretin response [5] [4]. The choice between dietary regimens should, therefore, be informed by a deep understanding of these underlying insulinotropic pathways, which continue to offer valuable targets for future diabetes therapeutics and personalized nutrition strategies.

{Abstract} The mediobasal hypothalamus (MBH) serves as a critical nutrient-sensing center for systemic metabolic regulation. Emerging research demonstrates that the metabolism of the branched-chain amino acid leucine within the MBH is a previously unrecognized mechanism that couples central nutrient sensing with the control of hepatic glucose production (HGP). This neural circuit is essential for maintaining glucose homeostasis and its dysregulation may contribute to hyperglycemia. This guide compares the efficacy of this specific signaling pathway against other dietary and central regulatory mechanisms, providing a focused analysis for the development of therapeutic strategies targeting brain-liver communication.

{1 Introduction} The central nervous system, particularly the hypothalamus, plays a pivotal role in regulating peripheral glucose metabolism. While the arcuate nucleus (ARC) of the MBH is known to integrate hormonal signals like insulin and leptin to influence energy and glucose homeostasis, its role as a sensor for specific nutrients, such as amino acids, has been elucidated more recently. The discovery that hypothalamic leucine metabolism can directly regulate HGP provides a novel axis for understanding how high-protein diets might influence glucose control. This guide details the experimental evidence for this pathway, juxtaposes it with other regulatory mechanisms, and provides the methodological toolkit required for its investigation.

{2 The Hypothalamic Leucine-Sensing Pathway: Mechanism and Key Experiments}

{2.1 Core Signaling Pathway} Central leucine sensing is a multi-step process initiated in the MBH. Leucine is first transaminated to α-ketoisocaproic acid (KIC) by the enzyme branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase (BCAT). KIC is then metabolized via branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase (BCKDH). This biochemical network is notably insensitive to rapamycin, indicating independence from the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, and is also independent of acetyl- and malonyl-CoA. The signaling cascade ultimately requires functional ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels to transmit the signal that suppresses HGP [7] [8].

The diagram below illustrates this specific signaling pathway from hypothalamic leucine sensing to the suppression of liver glucose production.

{2.2 Key Experimental Evidence} The foundational evidence for this pathway comes from a series of sophisticated clamp studies in rodent models. The key findings from these experiments are summarized in the table below.

| Experimental Intervention | Key Outcome on Blood Glucose / HGP | Interpretation & Mechanistic Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Central (MBH) Leucine Infusion [7] | Lowered blood glucose; Suppressed HGP [7] | The MBH is a direct site of leucine sensing for glucose regulation. |

| Central KIC Infusion [7] | Lowered blood glucose [7] | Leucine must be metabolized to KIC to exert its effect. |

| BCAT Inhibitor (Aminooxyacetic acid) [7] | Blocked leucine-induced suppression of HGP [7] | Confirms the necessity of the first metabolic step (leucine to KIC). |

| BCKDH Kinase (BCKDK) Overexpression [7] | Attenuated leucine-induced suppression of HGP; Caused hyperglycemia after a meal [7] | Inhibiting KIC metabolism disrupts the pathway and impairs glucose homeostasis. |

| KATP Channel Blockade | Blocked leucine-induced suppression of HGP [7] | KATP channel activity is a mandatory final step in the signal transduction. |

| MCD Overexpression (blocks malonyl-CoA accumulation) | Did not block leucine-induced suppression of HGP [7] | The pathway is independent of malonyl-CoA sensing. |

| Rapamycin Co-infusion (blocks mTOR) | Did not block leucine-induced suppression of HGP [7] | The pathway is independent of the mTOR signaling cascade. |

{2.3 Detailed Experimental Protocol} To investigate this pathway, researchers employ a combination of stereotaxic surgery, central infusions, and pancreatic-euglycemic clamp techniques.

- Animal Models and Surgery: Studies are performed in male Sprague-Dawley rats (10-12 weeks old) or mice (e.g., SUR1-null models). Animals undergo stereotaxic surgery for the implantation of a chronic cannula directed into the third cerebral ventricle (ICV) or bilaterally into the MBH. Correct placement is verified post-mortem [7].

- Central Infusions: After recovery, fasted animals receive continuous ICV or MBH infusions of test compounds. These include:

- Leucine: The primary amino acid of interest.

- KIC: The first metabolite of leucine.

- Inhibitors: Such as aminooxyacetic acid (BCAT inhibitor), α-chloroisocaproate (BCKDH inhibitor), or KATP channel blockers like glibenclamide.

- Control: Artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) is used as a vehicle control [7].

- Pancreatic-Euglycemic Clamp: During the central infusion, a basal pancreatic clamp is initiated. This technique involves the infusion of somatostatin to suppress endogenous insulin and glucagon secretion, while insulin is replaced at a basal rate to maintain fasting levels. This creates a steady hormonal background, allowing researchers to isolate the effect of the central intervention on HGP without the confounding effects of variable peripheral hormone levels. Glucose production is traced with [3-³H]glucose [7].

- Molecular Interventions: To establish causality, genetic tools are used. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors are injected into the MBH to overexpress genes of interest (e.g., BCKDK to inhibit BCKDH) or control proteins (e.g., GFP) [7].

The workflow of a typical experiment integrating these components is visualized below.

{3 Comparative Efficacy: Central Leucine vs. Other Regulatory Systems}

{3.1 Comparison with Other Central Nutrient-Sensing Pathways} The hypothalamic leucine-sensing pathway operates distinctly from other well-characterized central nutrient-sensing mechanisms. The following table provides a detailed comparison.

| Regulatory Pathway / Signal | Key Molecular Components | Primary Metabolic Outcome | Distinction from Leucine Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothalamic Leucine | BCAT, BCKDH, KATP channels | Suppresses HGP [7] [8] | Unique reliance on BCAA catabolism; mTOR-independent; malonyl-CoA-independent. |

| Central Insulin [9] | Insulin receptor, IRS/PI3K, KATP channels | Suppresses HGP (reduces gluconeogenesis & glycogenolysis) [9] | Signals energy sufficiency; acts primarily via inhibition of AgRP neurons; impaired in insulin resistance. |

| Central Leptin [9] | Leptin receptor, JAK/STAT, Melanocortin system | Modulates HGP (decreases glycogenolysis, increases gluconeogenesis) [9] | Signals adiposity; complex effects on hepatic glucose fluxes; involves POMC neurons. |

| Central Fatty Acids | Malonyl-CoA, CPT-1, KATP channels | Suppresses HGP [9] | Relies on de novo lipid synthesis and malonyl-CoA accumulation, a step bypassed by leucine signaling [7]. |

{3.2 Comparison with Peripheral Diets and Interventions} Placing the central leucine mechanism in the context of whole-diet interventions reveals a complex picture of how protein intake might influence glucose control.

| Dietary / Intervention Strategy | Reported Impact on Glucose Control | Potential Link to Central Leucine Signaling |

|---|---|---|

| High-Protein (HP) Diet [10] [11] | Improves HbA1c, fasting glucose, and insulin resistance; effects often tied to weight loss [10] [11]. | Increased dietary protein elevates plasma BCAAs, potentially enhancing central leucine sensing and contributing to HGP suppression. |

| Normal-Protein (NP) Diet [10] | Also improves glucose control when it results in equivalent weight loss [10]. | Suggests that achieved weight loss is a dominant factor, and the specific leucine mechanism may be one of several beneficial mediators. |

| Low-Carbohydrate Diets (e.g., LoBAG) [11] [12] | Significant reduction in HbA1c and 24-h glucose profiles [11] [12]. | These diets are often high in protein, suggesting a potential synergistic effect between low glucose availability and enhanced central leucine signaling. |

| Intermittent Leucine-Deprivation [13] | Shown to intervene in type 2 diabetes in db/db mice [13]. | Provides a contrasting approach, suggesting that modulating rather than increasing leucine levels can be therapeutic, highlighting the pathway's complexity. |

{4 The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents} To experimentally probe the hypothalamic leucine-sensing pathway, the following reagents and tools are essential.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose in Research |

|---|---|

| Stereotaxic Apparatus | Precise surgical implantation of guide cannulae into the MBH or third ventricle for central infusions. |

| Chronic Indwelling Cannulae (ICV/MBH) | Allows for repeated or continuous delivery of compounds directly to the brain region of interest. |

| Aminooxyacetic Acid (AOAA) | A pharmacological inhibitor of BCAT; used to block the first step of leucine metabolism and validate its necessity [7]. |

| α-Chloroisocaproate (α-CIC) | A pharmacological inhibitor of BCKDH; used to block the metabolism of KIC [7]. |

| KATP Channel Modulators (e.g., Glibenclamide, Diazoxide) | To open or block KATP channels and test their requirement in the signaling cascade [7]. |

| Pancreatic-Euglycemic Clamp Setup | The gold-standard method for in vivo assessment of HGP and peripheral tissue insulin sensitivity under controlled conditions. |

| AAV Vectors (e.g., AAV-BCKDK, AAV-MCD) | For targeted genetic manipulation (overexpression or knockdown) of specific pathway components within the MBH [7]. |

| [3-³H]Glucose Tracer | Enables the precise measurement of the rate of HGP during clamp studies via isotope dilution. |

{5 Discussion and Research Implications} The elucidation of the hypothalamic leucine-sensing pathway represents a significant advance in understanding brain-liver communication. Its independence from the mTOR and malonyl-CoA pathways suggests a previously unknown biochemical network within the MBH that is dedicated to amino acid sensing. From a therapeutic perspective, this pathway offers a promising target for drug development aimed at restoring central nutrient sensing in conditions like type 2 diabetes. However, the human translatability requires careful consideration, as chronic elevation of plasma BCAAs is also epidemiologically associated with insulin resistance. This paradox may be explained by potential "leucine resistance" in the hypothalamus under obese conditions or by opposing, potentially detrimental, effects of chronic high leucine on the liver, such as promoting triglyceride accumulation via a myostatin-AMPK pathway [14]. Therefore, therapeutic strategies would need to precisely target the central pathway without causing systemic or hepatic side effects. Future research should focus on identifying the exact molecular sensors downstream of KIC metabolism and the detailed neurocircuitry that relays the signal from the MBH to the liver.

Incretin hormones, primarily glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), play a pivotal role in metabolic homeostasis by amplifying glucose-stimulated insulin secretion following nutrient ingestion [15]. This physiological phenomenon, known as the incretin effect, accounts for 50-70% of postprandial insulin responses in healthy individuals [15]. While carbohydrates represent the classical stimulus for incretin release, emerging evidence demonstrates that protein digestion serves as a potent secretagogue for both GLP-1 and GIP, though with distinct activation patterns [16] [17]. Understanding these protein-mediated pathways provides crucial insights for developing nutritional strategies and pharmacological interventions for metabolic disorders, particularly in the context of comparing high-protein diets against standard diets for glucose control. This review systematically compares the mechanisms and efficacy of protein-induced GLP-1 and GIP secretion, integrating recent experimental findings to elucidate their differential activation patterns and therapeutic implications.

Physiological Fundamentals of Incretin Hormones

GLP-1 and GIP: Origin and Core Functions

GLP-1 and GIP are peptide hormones secreted by enteroendocrine cells in response to nutrient ingestion. GIP is primarily produced by K cells located in the upper portion of the gastrointestinal tract (duodenum and jejunum), while GLP-1 is secreted by L cells concentrated in the distal gut (ileum and colon) [15]. Both hormones function as incretins, potentiating glucose-dependent insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells, but exhibit complementary physiological roles: GLP-1 suppresses glucagon secretion and delays gastric emptying, whereas GIP exerts glucagonotropic effects during hypoglycemia [15]. Beyond their insulinotropic effects, both hormones influence central appetite regulation, with GLP-1 demonstrating particularly potent satiety-promoting properties [15] [18].

Receptor Signaling and Metabolic Integration

GLP-1 and GIP initiate signaling cascades by binding to specific class B G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) – GLP-1R and GIPR, respectively [15] [19]. These receptors exhibit distinct tissue distribution patterns: GIPR is expressed in pancreatic islets, brain, and adipocytes, while GLP-1R is found in pancreas, brain, and gastrointestinal tract [15]. Despite shared signaling pathways such as adenylate cyclase/cAMP activation, they engage distinct downstream effectors; in murine pancreatic β-cells, GLP-1 activates both Gαs and Gαq proteins, whereas GIP selectively activates Gαs [15]. This differential signaling contributes to their unique metabolic profiles and therapeutic applications.

Comparative Analysis: Protein-Induced GLP-1 vs. GIP Secretion

Quantitative Secretion Patterns

Recent human investigations directly comparing incretin responses to isolated protein versus carbohydrate ingestion reveal distinct secretion dynamics. A 2025 cross-over study examining isocaloric whey protein-only (1.2 g·kg⁻¹) and carbohydrate-only drinks demonstrated that protein stimulates significantly greater GLP-1 release, while carbohydrates elicit a more pronounced GIP response [16]. The temporal secretion patterns also differ, with protein-induced GLP-1 remaining elevated for extended periods (>240 minutes) compared to the more transient GIP response to carbohydrates [16].

Table 1: Comparative Hormonal Responses to Protein vs. Carbohydrate Ingestion

| Parameter | Whey Protein (1.2 g·kg⁻¹) | Carbohydrate | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| GLP-1 response | Significantly increased | Moderate increase | p < 0.001 (PRO > CHO) |

| GIP response | Moderate increase | Significantly increased | p < 0.001 (CHO > PRO) |

| Insulin response | Moderate increase | Significantly increased | p < 0.001 (CHO > PRO) |

| Response duration | GLP-1 remains elevated >240min | Transient response | Not specified |

Table 2: Nutrient Composition and Experimental Conditions

| Factor | Whey Protein Condition | Carbohydrate Condition |

|---|---|---|

| Energy content | Isoenergetic | Isoenergetic |

| Macronutrient | 1.2 g·kg⁻¹ whey protein | Matched carbohydrate quantity |

| Study population | 14 healthy, moderate-to-well-trained participants | Same participants |

| Design | Randomized, balanced cross-over | Randomized, balanced cross-over |

Synergistic Effects of Protein with Other Nutrients

The combination of protein with specific micronutrients potently enhances GLP-1 secretion. Emerging evidence indicates that co-ingestion of protein and calcium generates synergistic effects on GLP-1 release, potentially mediated by calcium-sensing receptors on intestinal L-cells [17]. This synergy produces some of the highest reported physiological concentrations of GLP-1 following nutrient ingestion, suggesting strategic nutrient combinations could optimize endogenous incretin secretion for metabolic benefits [17].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Human Intervention Protocols

The standard methodology for investigating protein-induced incretin secretion involves randomized, balanced cross-over designs with isocaloric nutrient challenges [16]. Participants typically report after an overnight fast, with intravenous catheters inserted for serial blood collection. Test beverages include protein-only (e.g., whey isolate) and carbohydrate-only formulations, administered in randomized order on separate days. Blood samples are collected at fasting baseline and at regular intervals post-ingestion (e.g., every 30-60 minutes for 4+ hours) for hormone and metabolite analyses [16]. This protocol enables direct within-subject comparison of hormonal responses while controlling for potential confounding factors.

Analytical Techniques and Assessments

Plasma GLP-1 and GIP concentrations are quantified via specific immunoassays that distinguish active forms (GLP-1₇–₃₆ amide and GIP₁–₄₂) from inactive metabolites [16] [17]. Simultaneous measurement of glucose, amino acids, insulin, and glucagon provides comprehensive metabolic profiling. For protein metabolism studies, urinary nitrogen excretion serves as an indicator of protein degradation and amino acid oxidation, with collections typically performed in consecutive batches over 24 hours to assess temporal patterns [16].

Diagram 1: Protein-mediated Incretin Secretion Pathway. This diagram illustrates the sequential process from protein ingestion to amino acid absorption, stimulation of intestinal endocrine cells, hormone secretion, receptor binding, and ultimately potentiation of glucose-dependent insulin secretion.

Research Reagents and Methodological Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Protein-Incretin Axis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Sources | Whey isolate, casein, plant proteins | Standardized protein challenges for incretin response studies |

| Hormone Assays | GLP-1₇–₃₆ amide ELISA, GIP₁–₄₂ RIA | Quantification of active incretin forms in plasma samples |

| Metabolic Analyzers | Glucose analyzers, amino acid profilers | Concurrent metabolic parameter assessment |

| Receptor Agonists/Antagonists | Exendin-4 (GLP-1R agonist), GIPR antibodies | Mechanistic studies of receptor-specific contributions |

| Cell Models | STC-1, GLUTag, primary intestinal cultures | In vitro screening of secretagogue potential |

Therapeutic Implications and Research Translation

Nutritional Strategies for Incretin Modulation

Strategic dietary approaches can optimize endogenous incretin secretion for metabolic benefits. Evidence-based nutritional interventions include: (1) prioritizing dietary protein from diverse sources (lean meats, fish, eggs, legumes), (2) combining protein with fiber-rich foods to enhance GLP-1 secretion, (3) incorporating healthy fats (olive oil, avocados, nuts) that augment GLP-1 release, and (4) practicing meal sequencing (consuming protein and vegetables before carbohydrates) to potentiate postprandial incretin responses [20]. These approaches provide widely accessible, cost-effective alternatives to pharmacological interventions for enhancing hormone release [17].

Pharmacological Applications and Drug Development

Understanding protein-mediated incretin secretion informs the development of next-generation therapeutics. The differential secretion patterns of GLP-1 and GIP following protein ingestion have inspired novel dual receptor agonists (e.g., tirzepatide) that simultaneously engage both GLP-1R and GIPR, demonstrating superior efficacy for weight loss and glycemic control compared to selective GLP-1 receptor agonists [18] [21]. Interestingly, both GIPR activation and blockade can enhance the weight-reducing effects of GLP-1R agonism, suggesting complex receptor-specific mechanisms that can be therapeutically exploited [21].

Diagram 2: Research Translation from Basic Science to Therapeutics. This diagram outlines the pathway from fundamental discoveries about protein-induced incretin secretion to the development of pharmacological interventions that harness these mechanisms for metabolic disease treatment.

Protein digestion activates distinct incretin-mediated pathways, with preferential stimulation of GLP-1 over GIP secretion. This differential activation pattern, coupled with the synergistic effects of protein combined with specific micronutrients like calcium, provides a scientific foundation for nutritional strategies targeting endogenous incretin enhancement. The mechanistic insights from protein-incretin research continue to drive innovation in therapeutic development, particularly in the design of multi-receptor agonists that mimic the coordinated hormone secretion observed with nutrient ingestion. Future research should focus on optimizing protein sources, quantities, and timing to maximize metabolic benefits, while exploring individual variability in response to protein-mediated incretin secretion for personalized nutrition approaches to glucose control.

Intestinal glucose absorption is a critical process for maintaining systemic energy balance, primarily mediated by the specialized transporters Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 1 (SGLT1) and Glucose Transporter 2 (GLUT2). Understanding the modulation of these transporters is essential for developing new strategies to manage hyperglycemia, a hallmark of metabolic diseases. This guide provides a comparative analysis of how different interventions—specifically high-protein diets and pharmaceutical agents—affect these transporters and overall glycemic control. Framed within broader research on the efficacy of high-protein versus standard diets, this review synthesizes current experimental data to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals about the mechanisms and potential applications of these modulatory approaches.

Transporter Mechanisms and Modulation Pathways

Glucose absorption in the small intestine involves coordinated actions of specific transporters. At low luminal glucose concentrations (typically <30 mM), SGLT1 on the apical membrane of enterocytes mediates active glucose uptake via a sodium-coupled mechanism [22]. Once inside the cell, glucose exits through the basolateral membrane into circulation via GLUT2, which facilitates passive diffusion [22]. At high luminal glucose concentrations, additional mechanisms may contribute, including paracellular transport and potential apical insertion of GLUT2 [22] [23].

Recent research has identified multiple pathways for modulating these transporters, ranging from dietary interventions to hormonal and pharmaceutical regulation. The following diagram illustrates the key mechanisms by which high-protein diets and the hormone estrogen regulate this system, based on recent findings.

Diagram 1: Signaling Pathways in Glucose Absorption Modulation. This figure illustrates the distinct mechanisms by which high-protein diets (yellow nodes) and estrogen (red nodes) modulate systemic glucose control, ultimately converging on improved postprandial glucose outcomes (blue nodes). The high-protein diet pathway involves hypothalamic signaling and GLP-1 secretion, while the estrogen pathway directly regulates transporter expression via ERα and PKC signaling.

Comparative Efficacy of Dietary Interventions

High-Protein vs. Standard Nutritional Formulas

Clinical studies directly compare the effects of diabetes-specific high-protein nutritional formulas (DSNF-Pro) against standard nutritional formulas (STNF). The quantitative outcomes from a recent cross-over clinical trial are summarized below.

Table 1: Effects of High-Protein vs. Standard Nutritional Formulas on Glycemic Response in Prediabetes [24] [25]

| Parameter | DSNF-Pro | STNF | Relative Change | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postprandial Glucose iAUC | Significantly Lower | Reference | -73.4% | 0.0001 |

| Postprandial C-peptide iAUC | Significantly Lower | Reference | -36.4% | 0.0001 |

| Postprandial Insulin iAUC | No Significant Difference | No Significant Difference | Not Significant | N/S |

| Carbohydrate Content (g/serving) | 12.0 | 21.0 | -42.9% | - |

| Protein Content (g/serving) | 12.0 | 4.9 | +144.9% | - |

This table demonstrates that DSNF-Pro, characterized by higher protein and lower carbohydrate content, significantly improves postprandial glycemic response without increasing insulin secretion, suggesting enhanced insulin sensitivity [24] [25].

Broader Dietary Pattern Comparisons

Beyond specific formulas, various dietary patterns also significantly impact glycemic control and transporter activity. Research across different patient populations, including those with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), provides valuable comparative insights.

Table 2: Efficacy of Broader Dietary Interventions on Glycemic Control [26] [27] [28]

| Dietary Intervention | Population | Key Glycemic Outcomes | Effect Size / Statistical Significance | Proposed Impact on SGLT1/GLUT2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Protein Diet (HPD) | T2DM | ↓ Mean 24-h integrated glucose area; ↓ HbA1c | 40% reduction in glucose AUC; HbA1c ↓ 0.8% [6] | Not directly measured, but systemic improvement suggests indirect modulation. |

| DASH Diet | GDM | ↓ Fasting Blood Glucose (FBG); ↓ 2h Postprandial Glucose (2h-PBG); ↓ HOMA-IR | SMD = -2.35 for FBG; SMD = -1.41 for 2h-PBG [26] | Not directly measured. |

| Low-Carbohydrate Diet (LCD) | T2DM | ↓ HbA1c (short-term); improved insulin sensitivity (short-term) | Significant reduction in 16/21 studies [28] | Likely reduces functional load on SGLT1/GLUT2 by limiting substrate availability. |

| Low-Glycemic Index (GI) Diet | GDM | ↓ Risk of macrosomia; improved postprandial glucose regulation | OR = 0.12 for macrosomia [26] | May influence expression/activity via reduced glucose flux and hormonal responses. |

The DASH diet shows the most potent effects on fasting and postprandial glucose in GDM, while HPDs and LCDs demonstrate significant benefits in T2DM management [26] [27] [28].

Experimental Models and Protocols

Key Methodologies for Studying Transporter Function

Understanding the modulation of SGLT1 and GLUT2 relies on robust experimental models, ranging from cellular systems to whole-organ perfusion.

Table 3: Key Experimental Protocols in Intestinal Glucose Absorption Research

| Experimental Model | Protocol Overview | Key Measurements | Context of Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture (Caco-2/TC7) | Differentiated human intestinal epithelial cell monolayers grown in transwell plates. Treated with compounds (e.g., dexamethasone, estrogen) for specified durations. [29] [30] | Glucose uptake assays (e.g., using 2-deoxy-D-glucose); Western blot for transporter protein expression; qPCR for mRNA levels. [30] | Mechanistic studies of hormonal and drug effects on transporter expression and function. |

| Vascularly Perfused Rat Intestine | Isolation and perfusion of the entire rat small intestine with a physiological buffer. Luminal and vascular infusions of glucose and specific inhibitors. [23] | Absorption quantified via radioactive tracers (14C-D-glucose). Paracellular transport assessed with 14C-D-mannitol. [23] | Quantifying contributions of transcellular (SGLT1/GLUT2) vs. paracellular glucose absorption pathways. |

| Using Chamber Experiments | Ex vivo segments of mouse duodenum mounted in chambers separating mucosal and serosal sides. [29] | Electrogenic glucose transport measured as short-circuit current (Isc). | Functional ex vivo assessment of glucose absorption capacity in tissue from different treatment groups. |

| Human Cross-Over Clinical Trials | Participants (e.g., with prediabetes) consume test products (DSNF-Pro vs. STNF) on different visits with washout periods. [24] [25] | Postprandial plasma glucose, serum insulin, and C-peptide measured over 3 hours. Incremental Area Under the Curve (iAUC) calculated. [24] [25] | Direct evaluation of the glycemic impact of dietary interventions in a human physiological context. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs critical reagents used in the featured experiments to study SGLT1 and GLUT2 function.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Glucose Transporter Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Phlorizin | Potent and specific competitive inhibitor of SGLT1. | Used in perfused intestine models to block apical SGLT1 activity, allowing quantification of its contribution to total glucose absorption. [23] |

| Phloretin | Inhibitor of facilitative glucose transporters, including GLUT2. | Applied in vascularly perfused rat intestine to block basolateral GLUT2, demonstrating its critical role in glucose efflux. [23] |

| 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose | Non-metabolizable glucose analog. | Used in Caco-2/TC7 cell uptake assays to measure glucose transporter activity specifically, without interference from metabolism. [30] |

| 14C-D-Glucose | Radioactive tracer for glucose. | Enables sensitive and accurate quantification of glucose absorption kinetics in complex ex vivo models like the perfused intestine. [23] |

| Dexamethasone | Synthetic glucocorticoid. | In Caco-2/TC7 cells, it dose-dependently upregulates SGLT1 expression and increases glucose transport, modeling drug-induced hyperglycemia. [30] |

| siRNA (ERα/ERβ) | Silences specific gene expression. | Used in SCBN cell lines to demonstrate that estrogen's upregulation of SGLT1/GLUT2 is mediated specifically by ERα, not ERβ. [29] |

Discussion and Research Implications

The comparative data indicates that high-protein diets and diabetes-specific nutritional formulas achieve significant improvements in glycemic control primarily through systemic effects, such as enhanced insulin sensitivity, increased GLP-1 secretion, and reduced hepatic glucose output, rather than direct inhibition of intestinal glucose transporters [24] [27] [25]. This is a distinct mechanism compared to the direct SGLT1/GLUT2 modulation observed with pharmaceutical agents like dexamethasone or hormonal influences like estrogen [29] [30].

The finding that estrogen enhances SGLT1 and GLUT2 expression via an ERα-PKC pathway provides a plausible physiological explanation for observed fluctuations in glucose tolerance during the menstrual cycle and highlights a significant sex-based variable in glucose metabolism research [29]. Conversely, the pro-hyperglycemic effect of dexamethasone, a widely used anti-inflammatory drug, which potently induces SGLT1 expression, reveals a key mechanism for a common clinical side effect [30].

From a drug development perspective, the direct inhibition of SGLT1 remains a valuable therapeutic target for hyperglycemia, as evidenced by the development of SGLT inhibitors [22]. However, the dietary strategies reviewed here, particularly high-protein and low-carbohydrate diets, offer a complementary approach by reducing the functional load on these transporters and improving whole-body glucose regulation through multiple pathways. Future research should focus on elucidating the precise molecular interactions between dietary components, gut hormones, and transporter regulation, and explore personalized nutrition strategies based on genetic background, sex, and gut microbiome composition.

Branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs)—leucine, isoleucine, and valine—are essential nutrients that exert a complex and dual influence on glucose metabolism. While they are well-known for their role in stimulating protein synthesis, their impact on insulin sensitivity presents a paradox that is of critical importance to researchers and drug development professionals. On one hand, acute postprandial elevations of BCAAs, particularly leucine, can signal nutrient abundance and trigger pathways that improve glycemic control [27] [31]. On the other hand, chronically elevated fasting levels of BCAAs are strongly and consistently associated with obesity, insulin resistance, and the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes (T2D) [32] [33] [34]. This review synthesizes current experimental data to objectively compare these opposing roles, framing the evidence within the broader thesis on the efficacy of high-protein diets for glucose control.

The Beneficial Face: Mechanisms of BCAA-Induced Insulin Sensitivity

Acute and postprandial exposure to BCAAs, especially within the context of a high-protein diet, can enhance glucose regulation through several well-documented mechanisms. The evidence for these benefits is summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Evidence for the Insulin-Sensitizing Effects of BCAAs and High-Protein Diets

| Mechanism/Effect | Supporting Experimental Data | Model System | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothalamic Signaling | [27] | Rodent Studies | Leucine sensing in the medio-basal hypothalamus activates a vagal signal to the liver, reducing hepatic glucose production. |

| Postprandial Glucose Control | [24] [35] | Human Clinical Trial (Prediabetes) | A high-protein, diabetes-specific formula reduced postprandial glucose iAUC by 73.4% (p=0.0001) without increasing insulin secretion. |

| Overall Glycemic Control (HbA1c) | [6] | Human Clinical Trial (T2DM) | A 5-week high-protein diet (30% protein) resulted in a 40% decrease in 24-hour glucose area response and a significant reduction in HbA1c. |

| Mitochondrial Biogenesis | [31] [36] | Pre-clinical & Clinical Evidence | Leucine activates the SIRT1-AMPK-PGC-1α axis, augmenting mitochondrial biogenesis and fatty acid oxidation in muscle and adipose tissue. |

| Muscle Mass Preservation | [37] [31] | Human Clinical Trials | Increased dietary protein during weight loss preserves skeletal muscle mass, the primary site for insulin-stimulated glucose disposal. |

Experimental Insight: Clinical Trials on Diabetes-Specific Nutritional Formulas

A recent open-label, cross-over clinical trial provides a clear example of a beneficial application. The study compared a high-protein, diabetes-specific nutritional formula (DSNF-Pro) against a standard nutritional formula (STNF) in subjects with prediabetes [24] [35].

- Methodology: Fifteen subjects consumed either DSNF-Pro (12g protein, 12g carbohydrate) or an isocaloric STNF (4.9g protein, 21g carbohydrate) after an overnight fast.

- Data Collection: Postprandial plasma glucose, serum insulin, and serum c-peptide were measured over 180 minutes to calculate incremental area under the curve (iAUC).

- Outcome: DSNF-Pro significantly reduced glucose iAUC by 73.4% and c-peptide iAUC by 36.4%, indicating markedly improved glucose handling without requiring increased insulin output [24] [35]. This demonstrates that the macronutrient composition, specifically high protein and low carbohydrate, is critical for glycemic outcomes.

The Adverse Face: BCAA-Induced Insulin Resistance

Paradoxically, despite the benefits of acute intake, chronic elevations in fasting BCAA levels are one of the earliest and strongest predictive biomarkers for the development of insulin resistance and T2D [32] [33] [34]. The mechanisms underlying this detrimental role are outlined below.

Table 2: Mechanisms Linking Elevated BCAAs to Insulin Resistance

| Proposed Mechanism | Experimental Support | Model System | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic mTOR Activation | [31] [33] | Cell & Rodent Studies | Chronic, as opposed to acute, activation of mTORC1-S6K1 signaling leads to serine phosphorylation of IRS-1, impairing insulin signaling. |

| Disrupted Tissue Catabolism | [33] [34] | Human & Rodent Studies | Obesity-related downregulation of BCKDH complex in adipose tissue and liver shunts BCAA oxidation to skeletal muscle, disrupting metabolic homeostasis. |

| Toxic Metabolite Accumulation | [33] [34] | Rodent Studies | Incomplete BCAA oxidation in muscle leads to accumulation of metabolites like 3-hydroxyisobutyrate (3-HIB), which promotes fatty acid uptake and lipid-induced insulin resistance. |

| Acute Impairment of Insulin Sensitivity | [32] | Rodent Study | A single acute infusion of BCAAs was sufficient to elevate blood glucose and impair whole-body insulin sensitivity during hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps. |

| AgRP Neuron Mediation | [32] | Rodent Study | Chemogenetic over-activation of AgRP neurons (as in obesity) impaired glucose tolerance, an effect normalized by acute BCAA reduction, linking neural pathways to BCAA-driven dysregulation. |

Experimental Insight: Acute BCAA Infusion and AgRP Neuron Studies

A pivotal 2024 study demonstrated that BCAAs per se can directly and acutely drive glucose dysregulation [32].

- Methodology: Catheter-guided frequent sampling was used in mice to assess the acute metabolic effects of a single BCAA infusion. Separately, hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps (the gold standard for assessing insulin sensitivity) were performed with constant BCAA infusion. The BCAA-lowering compound BT2 was used to test the converse.

- Data Collection: Frequent measurements of blood glucose and plasma insulin were taken. During clamps, the glucose infusion rate required to maintain euglycemia was measured.

- Outcome: Acute BCAA infusion elevated blood glucose and insulin and directly impaired whole-body insulin sensitivity. Conversely, a single BT2 injection improved glucose tolerance in obese mice. Furthermore, impaired glucose tolerance induced by stimulating AgRP neurons was fully normalized by lowering BCAAs, establishing a causal pathway [32].

Signaling Pathways: The Dual Molecular Mechanisms of BCAAs

The following diagrams illustrate the key signaling pathways that explain the dual roles of BCAAs, integrating the mechanisms discussed above.

Pathway 1: Insulin-Sensitizing signaling

Diagram 1: BCAA insulin-sensitizing pathways.

Pathway 2: Insulin-Resistance signaling

Diagram 2: BCAA insulin-resistance pathways.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Models

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Models for BCAA-Insulin Resistance Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Example Use in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperinsulinemic-Euglycemic Clamp | Gold-standard in vivo method for quantifying whole-body insulin sensitivity. | Used to demonstrate that acute BCAA infusion impairs insulin sensitivity in mice [32]. |

| BCAA-Lowering Compound (BT2) | Pharmacological inhibitor of BCKDK, increasing BCAA oxidation and lowering circulating BCAA levels. | Acute injection prevented fasting BCAA rise and improved glucose tolerance in high-fat-fed mice [32]. |

| DREADD (Designer Receptors) | Chemogenetic tool for selective activation or inhibition of specific neuronal populations. | Used to activate AgRP neurons in the hypothalamus, linking their activity to BCAA-mediated glucose dysregulation [32]. |

| Stable Isotope Tracers | Allow for tracing the metabolic fate of BCAAs and measuring tissue-specific oxidation rates. | Used in human studies to identify brown adipose tissue as a significant site of BCAA clearance [33]. |

| Mass Spectrometry (CG-MS/MS, HPLC-MS/MS) | Analytical platform for precise quantification of BCAAs and their downstream metabolites (e.g., 3-HIB, acylcarnitines). | Used to profile plasma metabolites and correlate BCAA levels with insulin resistance in human cohorts [34]. |

| AgRP-IRES-Cre Mouse Model | Genetic model enabling targeted manipulation of AgRP neurons, which are implicated in feeding behavior and glucose metabolism. | Critical for establishing the role of AgRP neurons in BCAA-driven glucose intolerance [32]. |

The relationship between BCAAs and insulin sensitivity is fundamentally dichotomous, hinging on context—acute versus chronic exposure, postprandial versus fasting states, and the metabolic health of the individual. High-protein diets can be effective for glucose control, as shown by the success of specialized nutritional formulas, largely through the acute signaling properties of leucine and the preservation of metabolically active muscle mass [24] [27] [6]. However, in states of energy overload and obesity, a cascade of events—including dysfunctional BCAA catabolism in adipose tissue, shunting to muscle, and accumulation of toxic metabolites—flips this relationship, establishing BCAAs as drivers of insulin resistance [32] [33] [34]. For drug development, this implies that therapeutic strategies should not seek to broadly inhibit BCAA action but rather to correct the underlying dysregulation of their metabolism, such as by enhancing BCAA oxidation in key tissues or targeting specific downstream effectors like 3-HIB. Future research should focus on the precise molecular switches that transition BCAA effects from beneficial to detrimental.

Clinical Translation: Implementing High-Protein Interventions in Diabetes Management

Medical Nutrition Therapy (MNT) represents a cornerstone in the prevention and management of diabetes, with particular emphasis on postprandial glucose regulation for overall glycemic control [38]. As prediabetes and diabetes continue to reach epidemic proportions globally, the development of targeted nutritional strategies has become increasingly crucial [38] [28]. Diabetes-Specific Nutritional Formulas (DSNF) have emerged as scientifically-designed interventions that modify macronutrient composition to optimize glycemic response. These formulas are characterized by their distinctive macronutrient profiles, which typically include reduced carbohydrate content, increased protein, elevated monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), and added dietary fiber [38] [39]. This review examines the composition and efficacy evidence for DSNFs, positioning them within the broader context of high-protein dietary strategies for glucose control, and provides researchers with methodological insights for evaluating their therapeutic potential.

Composition Analysis: DSNF Versus Standard Nutritional Formulas

Macronutrient Architecture

DSNFs are engineered with specific macronutrient modifications that differentiate them from standard nutritional formulas. The compositional adjustments are strategically designed to attenuate postprandial glycemic excursions while providing adequate nutritional support.

Table 1: Comparative Macronutrient Composition of DSNF Versus Standard Formulas

| Formula Type | Energy (kcal) | Protein (g) | Carbohydrates (g) | Fat (g) | MUFA Content | Dietary Fiber | Special Carbohydrates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSNF-Pro [38] | 140 | 12 | 12 | 6 | 60% of total fat | Included | Xylitol, Palatinose |

| Standard Formula [38] | 140 | 4.9 | 21 | 4.2 | Not specified | Not specified | Standard carbohydrates |

| DSNF (Nucare) [40] | 200 | 10.4 | 22.4 | 10.4 | 30.3% of total energy | Included | Allulose (D-psicose) |

| Standard ONS [40] | 200 | 7 | 30 | 6 | Not specified | Not specified | Standard carbohydrates |

Functional Components and Glycemic Modulation Mechanisms

The efficacy of DSNFs extends beyond basic macronutrient distribution to include specific functional components that actively modulate glucose metabolism:

- Carbohydrate Quality Modification: DSNFs incorporate low glycemic index (GI) carbohydrates such as palatinose, xylitol, and allulose (D-psicose), which slow digestion and absorption rates, thereby producing more gradual postprandial glucose elevations [38] [40].

- Protein Enrichment: High-protein DSNF variants provide approximately 12g of protein per serving, representing a significant increase compared to standard formulas (4.9g), which may enhance satiety and stimulate insulin secretion without disproportionate glucose elevation [38].

- Lipid Profile Optimization: The strategic inclusion of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), comprising up to 60% of total fat content in some formulations, contributes to improved insulin sensitivity and favorable lipid profiles [38] [39].

- Fiber Supplementation: Dietary fiber content in DSNFs delays gastric emptying and intestinal carbohydrate absorption, further blunting postprandial glycemic spikes [40].

Efficacy Evidence: Quantitative Clinical Outcomes

Effects on Glycemic Parameters

Randomized controlled trials and clinical studies have consistently demonstrated the superior glycemic efficacy of DSNFs compared to standard nutritional formulas across multiple parameters.

Table 2: Efficacy Outcomes of DSNF Versus Standard Formulas in Clinical Studies

| Study Design | Population | Intervention | Primary Outcomes | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open-label, cross-over clinical trial [38] [25] | 15 prediabetic adults | DSNF-Pro vs. STNF | ↓ 73.4% in glucose iAUC | p = 0.0001 |

| ↓ 36.4% in c-peptide iAUC | p = 0.0001 | |||

| No significant difference in insulin iAUC | Not significant | |||

| Open-label, crossover clinical trial [40] | 15 prediabetic adults | DSNF vs. standard ONS | ↓ Significant reduction in glucose iAUC | P < 0.0001 |

| ↓ Significant reduction in insulin iAUC | P = 0.0181 | |||

| ↓ Significant reduction in c-peptide iAUC | P < 0.0001 | |||

| Longitudinal pilot study [39] | 11 overweight/obese diabetic patients | DSNF for 4 weeks | ↑ Time in Range (TIR) from 64% to 75% | p = 0.01 |

| ↓ Time Above Range (TAR) from 34% to 23% | p = 0.02 |

Comparative Efficacy Against Other Dietary Interventions

The efficacy of DSNFs must be contextualized within the broader landscape of dietary interventions for glucose management:

- Low-Carbohydrate Diets (LCDs): A recent umbrella meta-analysis of 21 randomized controlled trials demonstrated that LCDs (≤130g carbohydrate/day) significantly reduce HbA1c in 16 of 21 studies, with substantial short-term improvements in glycemic control [28]. However, benefits attenuated over longer durations, highlighting sustainability challenges.

- High-Protein Diets: Systematic reviews indicate that high-protein diets (25-35% of energy intake) improve postprandial glycemia through increased insulin secretion, with protein source appearing more relevant in acute studies than longer interventions [41] [27].

- DASH and Low-GI Diets: A network meta-analysis of gestational diabetes management identified the DASH diet as most effective for reducing fasting blood glucose, while both DASH and Low-GI diets reduced adverse pregnancy outcomes [42].

Experimental Methodology for DSNF Evaluation

Standardized Clinical Trial Protocols

Robust evaluation of DSNF efficacy requires carefully controlled experimental designs with standardized protocols:

Laboratory Assessment Methodologies

Consistent laboratory techniques are essential for reliable comparison of DSNF efficacy across studies:

- Plasma Glucose Measurement: Enzymatic colorimetric glucose oxidase assays (e.g., ADAMS glucose GA-1171) provide precise quantification of glucose concentrations in EDTA-treated blood samples [38] [40].

- Insulin and C-Peptide Quantification: Radioimmunoassay methods (e.g., RK-400CT, C-peptide IRMA KIT) enable sensitive detection of insulin secretion and beta-cell function from serum separator tubes [38] [40].

- Data Analysis Parameters: Key efficacy endpoints include incremental Area Under the Curve (iAUC), maximum concentration (Cmax), and incremental maximal concentration (iCmax) for glucose, insulin, and c-peptide, typically analyzed using non-parametric tests like Wilcoxon's signed-rank test for paired comparisons [38] [40].

Mechanistic Insights: Metabolic Pathways of DSNF Action

The glycemic benefits of DSNFs are mediated through multiple physiological mechanisms that extend beyond simple carbohydrate reduction:

Neurological and Endocrine Pathways

Emerging research elucidates sophisticated mechanisms through which high-protein DSNFs influence glycemic control:

- Hypothalamic Nutrient Sensing: Branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), particularly leucine, directly access the medio-basal hypothalamus through the permeable microvasculature in the arcuate nucleus, where metabolic conversion to oleoyl-CoA activates hypothalamic ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels [27]. This generates a neuronal signal transmitted via the vagus nerve to the liver, reducing hepatic glucose production through inhibition of gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis [27].

- Incretin-Mediated Effects: BCAAs stimulate secretion of gut hormones including glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP), which enhance the functional balance of pancreatic α and β cells, decreasing glucagon production while increasing insulin release [27].

- Insulin-Sparing Action: Clinical evidence indicates that DSNF-Pro significantly reduces postprandial glucose without increasing insulin secretion, as demonstrated by reduced c-peptide iAUC without significant changes in insulin iAUC, suggesting improved insulin sensitivity and reduced beta-cell demand [38].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for DSNF Investigation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for DSNF Investigations

| Category | Specific Reagents/Assays | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Collection | EDTA-treated tubes, Serum Separator Tubes (SST) | Sample collection and preservation | Prevents coagulation, maintains sample integrity |

| Glucose Assessment | Enzymatic colorimetric glucose oxidase assay (ADAMS glucose GA-1171) | Plasma glucose quantification | Specific glucose oxidation reaction |

| Insulin Measurement | Radioimmunoassay (RK-400CT) | Serum insulin detection | High sensitivity for low concentration peptides |

| C-Peptide Analysis | C-peptide IRMA KIT (Beckman Coulter) | Beta-cell function assessment | Distinguishes endogenous from exogenous insulin |

| Body Composition | Bioelectrical impedance analysis (Inbody 970) | Anthropometric evaluation | Quantifies muscle mass, fat mass, body fat percentage |

| Continuous Monitoring | FreeStyle Libre CGM System (Abbott) | Real-time glycemic assessment | Measures interstitial glucose, calculates TIR, TAR, TBR |

| Dietary Assessment | CAN-Pro 6.0 Software | Nutritional intake analysis | Standardized nutrient composition database |

| Physical Activity | International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) | MET-min/week calculation | Quantifies energy expenditure across intensity levels |

Diabetes-Specific Nutritional Formulas represent a scientifically-validated approach to glycemic management through targeted macronutrient modification. Evidence from controlled clinical trials demonstrates that DSNFs significantly improve postprandial glycemic parameters compared to standard nutritional formulas, with high-protein variants exhibiting particular efficacy in reducing glucose excursions without proportionally increasing insulin secretion [38] [25] [40]. The mechanisms underlying these benefits involve complex interactions between nutrient composition, neurological signaling pathways, and endocrine responses [27].

Future research should address several critical knowledge gaps: (1) long-term efficacy and sustainability of DSNF interventions beyond acute postprandial studies; (2) comparative effectiveness of different protein sources (animal versus plant-based) within DSNF formulations; (3) personalized nutrition approaches to match specific DSNF compositions to individual metabolic phenotypes; and (4) potential synergistic effects between DSNFs and pharmacological antidiabetic agents. The ongoing development and refinement of DSNFs holds significant promise for enhancing medical nutrition therapy as both a preventive and management strategy across the diabetes spectrum.

The management of blood glucose levels is a critical focus in metabolic health research, particularly for conditions like prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Within this context, high-protein diets (HPDs), typically defined as providing >30% of total energy from protein or >1.0-1.2 g/kg/day, have emerged as a significant dietary strategy against standard diets [27]. These diets are thought to improve glycemic control through multiple mechanisms, including enhanced insulin sensitivity, increased satiety leading to weight loss, and direct signaling effects of amino acids on metabolic pathways [27]. However, simply increasing total daily protein intake does not tell the complete story. Emerging evidence suggests that the temporal distribution of protein intake across meals—the specific dosage per meal and the timing of consumption—plays a crucial role in optimizing metabolic outcomes and anabolic potential [43] [44]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of experimental data and methodologies to inform research on protein distribution strategies, with a specific focus on implications for glucose control.

Comparative Analysis: High-Protein vs. Standard Nutritional Formulas

Clinical trials directly comparing diabetes-specific nutritional formulas (DSNF) with standard formulas provide compelling evidence for the role of macronutrient composition in postprandial metabolism.

Table 1: Postprandial Metabolic Responses to Nutritional Formulas

| Metabolic Parameter | DSNF-Pro (High-Protein) | Standard Formula (STNF) | Relative Change (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postprandial Glucose iAUC | Significantly Reduced | Baseline | -73.4% | 0.0001 |

| Postprandial C-peptide iAUC | Significantly Reduced | Baseline | -36.4% | 0.0001 |

| Postprandial Insulin iAUC | No Significant Difference | No Significant Difference | N.S. | N.S. |

| Carbohydrate Content (g/serving) | 12.0 | 21.0 | -42.9% | - |

| Protein Content (g/serving) | 12.0 | 4.9 | +144.9% | - |

| Dietary Fiber Content (g/serving) | 5.0 | 0.84 | +495.2% | - |

Source: Adapted from Kim et al. (2025). An open-label, cross-over clinical trial in subjects with prediabetes (n=15) [24].

A recent open-label, cross-over clinical trial demonstrated the efficacy of a high-protein, diabetes-specific nutritional formula (DSNF-Pro) compared to a standard nutritional formula (STNF) in individuals with prediabetes. The DSNF-Pro provided 12g of protein and 12g of carbohydrates per 140 kcal serving, whereas the STNF provided 4.9g of protein and 21g of carbohydrates for the same caloric content [24]. As summarized in Table 1, the DSNF-Pro group exhibited a dramatic 73.4% reduction in postprandial glucose incremental Area Under the Curve (iAUC) and a 36.4% reduction in C-peptide iAUC, indicating a significantly improved glycemic response without a corresponding increase in insulin secretion [24]. This suggests that the high-protein, low-carbohydrate formulation improves glucose metabolism through enhanced insulin sensitivity rather than by increasing β-cell demand.

Experimental Protocol: Nutritional Formula Cross-Over Trial

Objective: To evaluate the effects of a high-protein, diabetes-specific nutritional formula (DSNF-Pro) versus a standard nutritional formula (STNF) on postprandial glycemic control, insulin, and C-peptide levels in subjects with prediabetes [24].

Methodology:

- Design: Open-label, randomized, cross-over clinical trial.

- Subjects: Fifteen adults with prediabetes (defined by HbA1c 5.6-6.4% or fasting blood glucose 100-125 mg/dL).

- Intervention: After a 10-12 hour overnight fast, subjects consumed either DSNF-Pro or STNF on separate visits, with a washout period of 1-14 days between visits.

- Blood Sampling: Venous blood samples were collected via catheter at fasting (0 min) and at 30, 60, 90, 120, and 180 minutes post-consumption.

- Sample Analysis:

- Plasma Glucose: Measured using an enzymatic colorimetric glucose oxidase assay.

- Serum Insulin and C-peptide: Measured using radioimmunoassay (RIA) kits.

- Data Analysis: The incremental Area Under the Curve (iAUC) for glucose, insulin, and C-peptide was calculated. Statistical comparisons were performed using Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test [24].

Protein Dosage Per Meal and Metabolic Utilization

A foundational question in protein distribution research involves determining the optimal dosage per meal to maximize metabolic utilization, particularly for musculoskeletal accretion, which is critical for overall metabolic health.

Single-Meal Protein Dosing and Muscle Protein Synthesis

Groundbreaking research has challenged the long-held belief that muscle protein synthesis (MPS) is maximized at a dose of approximately 20-25 grams of protein per meal. A rigorous study investigated the metabolic fate of ingested protein over a 12-hour period following a full-body resistance training session.

The study by Trommelen et al. (as reviewed by Trexler) involved administering 0g, 25g, or 100g of milk protein to trained males after exercise. The results revealed a clear dose-dependent relationship. While the 25g dose elevated protein synthesis, the 100g dose resulted in a significantly greater cumulative anabolic response. Crucially, the advantage of the large dose was its ability to extend the duration of the anabolic window; protein synthesis rates remained elevated for up to 12 hours, compared to a return to baseline by approximately 6 hours with the 25g dose [45]. This demonstrates that the body can effectively utilize large boluses of protein, primarily by sustaining a higher rate of protein synthesis over many hours, with only a negligible amount being oxidized ("wasted") [45].

Table 2: Protein Distribution Patterns in Resistance Training

| Parameter | Three High-Protein Meals (PRO3x) | Five High-Protein Meals (PRO5x) | Between-Group Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Protein Intake | Similar (Optimal per meal) | Similar (Optimal per meal) | Not Significant |

| Lean Mass Gain (kg) | 1.15 ± 1.54 | 0.63 ± 1.32 | N.S. |

| Vastus Lateralis CSA Gain (cm²) | 3.41 ± 3.79 | 2.53 ± 3.31 | N.S. |

| Knee Extension 1RM Gain (kg) | 19.08 ± 7.56 | 16.01 ± 5.17 | N.S. |

Source: Adapted from Randomized Controlled Trial (2025) in young, resistance-trained men (n=18 completers) over 8 weeks [43].

When protein intake is sufficient and energetically balanced, the frequency of distribution may be of secondary importance for body composition. An 8-week randomized trial with resistance-trained men compared consuming high-protein meals (>0.24 g/kg/meal) three times per day (PRO3x) versus five times per day (PRO5x). As shown in Table 2, both groups achieved significant and comparable gains in lean mass, muscle cross-sectional area (CSA), and strength, with no statistically significant differences between the protocols [43]. This indicates that for muscle anabolism, achieving an optimal per-meal dose (in this case, >0.24 g/kg/meal) is a key factor, and this can be effectively accomplished with either three or five meals per day.

Synergy with Time-Restricted Eating and Other Dietary Regimens

Integrating high-protein diets with other dietary strategies, such as time-restricted eating (TRE), creates a synergistic approach that can simultaneously improve body composition and metabolic health.

High-Protein Time-Restricted Eating

Research has demonstrated that combining TRE with high-protein intake can yield superior outcomes. A randomized controlled trial in women with overweight compared four groups: TRE with high protein (THP), TRE with regular protein, high protein only (HP), and regular protein only, with all groups undergoing resistance training and a calorie deficit.

Table 3: High-Protein TRE vs. Other Diets in Overweight Women

| Outcome Measure | TRE + High Protein (THP) | High Protein Only (HP) | TRE + Regular Protein | Regular Protein Only |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visceral Adipose Tissue (VAT) Reduction | Δ = -146.98 ± 12.66 (Greatest decrease) | Significant Reduction | Significant Reduction | Significant Reduction |

| Fat-Free Mass (FFM) Change | Δ = +1.06 ± 1.75 (Preserved) | Δ = +2.37 ± 0.64 (Increased) | Not Specified | Not Specified |

| Leptin Reduction | Significant (vs. Regular Protein Only) | Not Specified | Significant (vs. Regular Protein Only) | Baseline |

Source: Adapted from International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism (2025). 8-week RCT in young women with overweight (n=32) [46].

The results, summarized in Table 3, show that while all groups lost adipose tissue, the THP group exhibited the greatest reduction in visceral adipose tissue (VAT). Notably, the high-protein groups (THP and HP) were the only ones to show a significant increase in fat-free mass, demonstrating the power of elevated protein intake to preserve or even build muscle during a calorie-restricted diet—a critical factor for maintaining metabolic rate [46].

Comparison with Other Dietary Interventions for Glycemic Control

Other dietary interventions also show efficacy for glycemic control. A meta-analysis of eight randomized controlled trials concluded that fasting interventions (including intermittent fasting and TRE) significantly improved fasting blood glucose, HbA1c, and HOMA-IR (a measure of insulin resistance) [47]. Another umbrella meta-analysis found that low-carbohydrate diets (LCDs) provide substantial short-term improvements in HbA1c for patients with T2DM, though long-term sustainability varies [28]. A head-to-head comparison of intermittent energy restriction (IER), TRE, and continuous energy restriction (CER) in patients with obesity and T2DM found that all three improved HbA1c and body weight, but the IER group showed greater advantages in reducing fasting glucose and improving insulin sensitivity [48].

The following diagram synthesizes the mechanistic pathways through which high-protein diets, particularly those rich in leucine, are believed to exert their glucoregulatory effects, integrating findings from pre-clinical and clinical studies [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Methodologies

To conduct rigorous research in protein metabolism and glycemic control, specific tools and methodologies are essential. The following table details key components used in the featured experiments.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use in Cited Research |

|---|---|---|

| Intrinsically Labeled Milk Protein | Metabolic tracer to directly follow the fate, oxidation, and incorporation of ingested amino acids into body proteins. | Trommelen et al. used L-[1-13C]-phenylalanine and L-[ring-2H5]-phenylalanine labels to quantify protein metabolism over 12 hours [45]. |

| Stable Isotope Infusions (L-[ring-13C6]-phenylalanine) | Intravenous infusion of labeled amino acids to measure whole-body and muscle-specific protein synthesis and breakdown rates. | Used in conjunction with ingested labeled protein to create a comprehensive model of protein flux [45]. |

| Radioimmunoassay (RIA) Kits | High-sensitivity measurement of hormone concentrations in serum/plasma (e.g., insulin, C-peptide). | Used to measure serum insulin and C-peptide levels in the DSNF-Pro vs. STNF trial [24]. |

| Enzymatic Colorimetric Assays (Glucose Oxidase) | Standardized method for precise quantification of plasma glucose concentrations. | Used for all plasma glucose measurements in the nutritional formula clinical trial [24]. |

| Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA) | Gold standard for in vivo body composition analysis (fat mass, lean soft tissue mass, bone mineral density). | Used to assess lean mass changes in the protein distribution and TRE studies [43] [46]. |

| Muscle Biopsy & Analysis | Collection of muscle tissue for direct measurement of fractional synthesis rate (FSR), signaling pathways, and gene expression. | Vastus lateralis biopsies were used to measure muscle protein synthesis and molecular responses [45]. |

The evidence demonstrates that high-protein diets offer a significant advantage over standard diets for glycemic control, primarily by improving postprandial glucose responses and enhancing insulin sensitivity without necessarily increasing insulin secretion [24] [27]. The optimization of this strategy, however, depends on protein distribution. Key considerations for researchers and clinicians include:

- Per-Meal Dosage: The concept of a rigid upper limit for protein utilization per meal is outdated. Doses as high as 100g can be effectively utilized over a prolonged period, sustaining an elevated anabolic state, particularly when combined with exercise [45].

- Distribution Frequency: When per-meal protein intake meets a theorized optimal threshold (e.g., >0.24 g/kg/meal), distributing intake across three or more meals per day is effective for anabolism, with no clear superiority of more frequent feeding in balanced conditions [43] [44].