Glucose Prediction Model Showdown: A Comparative Analysis of Logistic Regression, LSTM, and ARIMA for Clinical and Research Applications

This article provides a comprehensive, evidence-based analysis of the predictive accuracy, clinical applicability, and operational trade-offs of three prominent glucose forecasting models: Logistic Regression, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, and...

Glucose Prediction Model Showdown: A Comparative Analysis of Logistic Regression, LSTM, and ARIMA for Clinical and Research Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive, evidence-based analysis of the predictive accuracy, clinical applicability, and operational trade-offs of three prominent glucose forecasting models: Logistic Regression, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, and the Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA). Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes recent findings on model performance across different prediction horizons and patient populations, from septic ICU patients to free-living individuals with diabetes. The review covers foundational principles, methodological deployment, optimization strategies to address common challenges like data scarcity and privacy, and a rigorous comparative validation. The objective is to guide the selection and development of robust, clinically actionable models for improving diabetes management and therapeutic development.

Foundations of Glucose Prediction: Understanding the Core Models and Clinical Imperatives

The Critical Need for Accurate Glucose Forecasting in Diabetes and Critical Care

Accurate forecasting of blood glucose levels is a cornerstone for modern diabetes management and critical care. It enables proactive interventions to prevent dangerous glycemic events, thereby reducing patient morbidity and mortality. Within this field, a key research focus involves the comparative evaluation of predictive models, including Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA), logistic regression, and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks. Each model offers distinct advantages and limitations, making them suitable for different clinical scenarios and prediction horizons. This guide provides an objective comparison of these models' performance, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform researchers and healthcare professionals in selecting the optimal tool for specific applications.

Performance Comparison at a Glance

The performance of ARIMA, logistic regression, and LSTM models varies significantly depending on the prediction horizon and the specific glycemic class of interest (hypoglycemia, euglycemia, or hyperglycemia). The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from comparative studies.

Table 1: Model Performance for 15-Minute Prediction Horizon (Recall Rates %) [1] [2]

| Glycemic Class | Logistic Regression | LSTM | ARIMA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL) | 98% | Underperformed Logistic Regression | Underperformed |

| Euglycemia (70-180 mg/dL) | 91% | Underperformed Logistic Regression | Underperformed |

| Hyperglycemia (>180 mg/dL) | 96% | Underperformed Logistic Regression | Underperformed |

Table 2: Model Performance for 1-Hour Prediction Horizon (Recall Rates %) [1] [2]

| Glycemic Class | Logistic Regression | LSTM | ARIMA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL) | Underperformed LSTM | 87% | Underperformed |

| Euglycemia (70-180 mg/dL) | Information Not Provided | Information Not Provided | Underperformed |

| Hyperglycemia (>180 mg/dL) | Underperformed LSTM | 85% | Underperformed |

Table 3: Summary of Model Strengths and Weaknesses

| Model | Best For | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | Short-term classification (e.g., 15-minute horizon), especially for hypoglycemia [1] [2]. | Performance degrades at longer prediction horizons [1]. |

| LSTM | Longer-term forecasting (e.g., 1-hour horizon), capturing complex temporal patterns [1] [3]. | Requires large amounts of training data; computationally complex [3]. |

| ARIMA | Small datasets; linear trends; computationally efficient [3]. | Poor performance on non-stationary data; struggles with complex nonlinear patterns and long-term dependencies [1] [3]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure the validity and reproducibility of comparative studies, researchers adhere to rigorous experimental protocols encompassing data collection, preprocessing, and model training.

Data Collection and Preprocessing

- Data Sources: Research typically utilizes two primary data sources: real-patient data from clinical cohort studies and in-silico data generated by simulators like the CGM Simulator (e.g., Simglucose v0.2.1). Real-patient data includes CGM readings, insulin dosing, and carbohydrate intake [1].

- Data Cleaning and Alignment: Raw data is pre-processed to address gaps and bad entries. Time-series data is aligned to a consistent frequency (e.g., 15-minute intervals). Measurements taken in very quick succession (e.g., within 5-minute windows) may be excluded to avoid over-representing a single glycemic episode [1] [4].

- Feature Engineering: For models that rely solely on CGM data, features are engineered from the glucose time series itself. These can include:

Model Training and Evaluation

- Outcome Definition: For classification tasks, glycemic states are defined as:

- Hypoglycemia: Glucose < 70 mg/dL

- Euglycemia: Glucose 70-180 mg/dL

- Hyperglycemia: Glucose > 180 mg/dL [1]

- Prediction Horizon: Models are trained to predict glucose levels at specific future time points, such as 15 minutes or 1 hour ahead [1].

- Performance Metrics: Models are evaluated using standard metrics, including:

- Precision: The proportion of correct positive predictions among all positive predictions.

- Recall (Sensitivity): The proportion of actual positives that were correctly identified. This is critical for detecting dangerous events like hypoglycemia [1].

- Accuracy: The overall proportion of correct predictions.

- F1-Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall [1].

- Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE): Commonly used for regression tasks to measure the average prediction error [3].

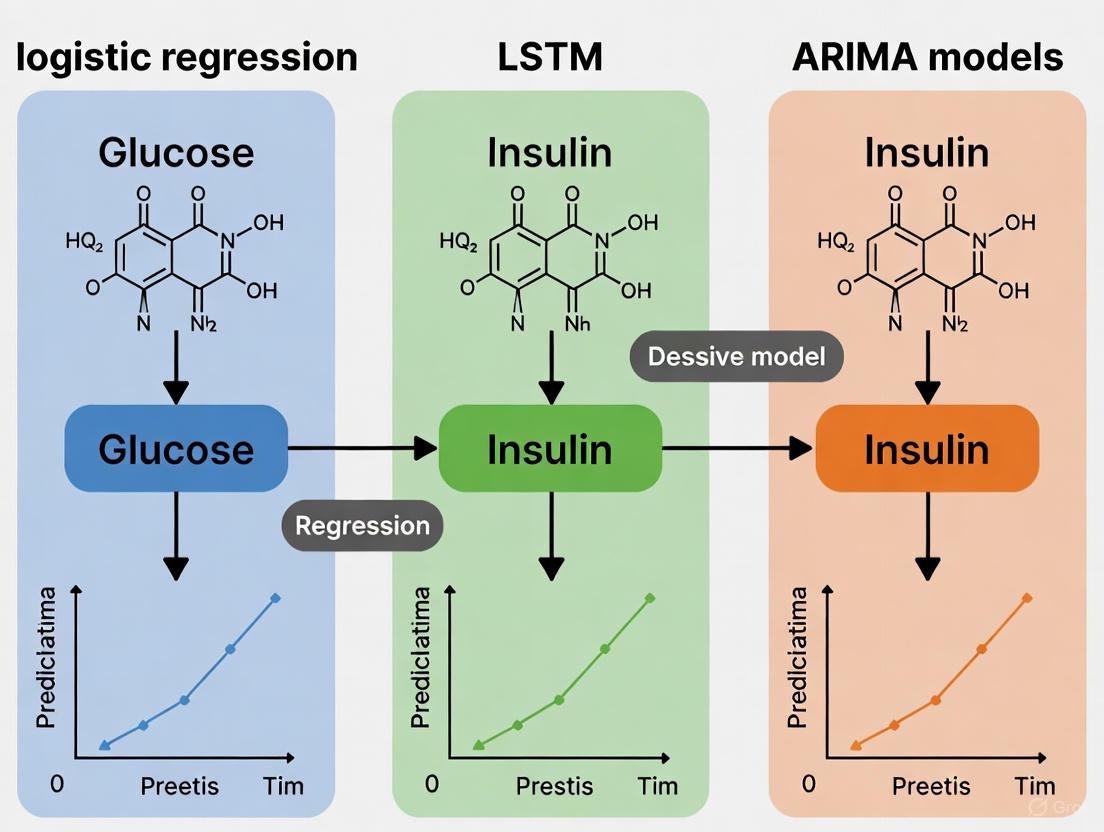

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Comparative Model Analysis. This diagram outlines the key stages in a typical study comparing glucose prediction models, from data preparation to final analysis.

Model Selection Logic

Choosing the right model depends on the specific clinical requirement, particularly the needed prediction horizon and the primary glycemic risk.

Figure 2: A Logic Flow for Selecting a Glucose Prediction Model. This chart guides the initial selection of a model based on key project constraints and goals.

The Researcher's Toolkit

Successful development and deployment of glucose forecasting models rely on a suite of essential computational and data resources.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Glucose Forecasting Research

| Tool / Resource | Function / Description | Relevance in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) Simulator | Software (e.g., Simglucose) that generates synthetic, physiologically plausible CGM data for in-silico testing [1]. | Allows for initial algorithm development and validation in a controlled environment before clinical trials. |

| Federated Learning (FL) Framework | A decentralized machine learning approach where models are trained locally on devices or servers, and only model parameters are shared [5]. | Addresses data privacy concerns by enabling collaborative model training without sharing sensitive patient data. |

| Specialized Loss Functions (e.g., HH Loss) | A cost-sensitive loss function that assigns a higher penalty to prediction errors in the hypoglycemic and hyperglycemic ranges [5]. | Improves model performance on critical glycemic excursions, which are often rare events in imbalanced datasets. |

| Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Data | Comprehensive annual time-series data on diabetes prevalence, deaths, and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) [3]. | Used for macro-level forecasting of diabetes burden to inform public health policy and resource allocation. |

| Time-Series Analysis Libraries (e.g., pmdarima) | Software libraries that provide implementations for models like ARIMA, often with automated parameter search [6]. | Accelerates model development and benchmarking by providing optimized, ready-to-use statistical models. |

The comparative analysis of ARIMA, logistic regression, and LSTM models reveals a clear trade-off between predictive accuracy, horizon, and computational complexity. No single model is universally superior. Logistic regression excels as a highly accurate and likely efficient tool for short-term classification of glycemic states, particularly for critical hypoglycemia prediction. In contrast, LSTM networks demonstrate stronger capabilities for longer-term forecasting by capturing complex, non-linear temporal dependencies, albeit with greater data and computational demands. ARIMA models, while computationally efficient, are consistently outperformed by machine learning approaches in handling the complexities of glucose dynamics. The choice of model must therefore be driven by the specific clinical application, available data, and required prediction horizon. Future research directions point towards hybrid, ensemble, and personalized models to further enhance accuracy and reliability in both individual patient management and population-level health forecasting.

Effective glucose management is crucial for individuals with diabetes to prevent both acute risks and long-term complications. The development of Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) systems has generated vast amounts of data, creating opportunities for predictive modeling to enhance clinical decision-making. Within this context, probabilistic classification models have emerged as valuable tools for forecasting glycemic events, enabling proactive interventions to prevent dangerous glucose excursions. This guide focuses on logistic regression as a fundamental yet powerful probabilistic classification technique, objectively comparing its performance with other modeling approaches including Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) models within the specific domain of glycemic event prediction.

The core strength of logistic regression lies in its ability to estimate the probability of a categorical outcome—in this case, whether a future glucose reading will fall into hypoglycemic, euglycemic, or hyperglycemic ranges. Unlike regression models that predict continuous glucose values, classification models directly address the clinical question of most relevance: "What is the risk of a future hypoglycemic or hyperglycemic event?" This probabilistic framework supports clinical decision-making by quantifying risk in an interpretable manner [1].

Model Comparison: Performance Across Prediction Horizons

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Extensive research has evaluated the performance of various models for predicting glycemic events across different time horizons. The table below summarizes key findings from a comprehensive 2023 study that directly compared logistic regression, LSTM, and ARIMA models for classifying hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL), euglycemia (70-180 mg/dL), and hyperglycemia (>180 mg/dL) at 15-minute and 1-hour prediction horizons [1].

Table 1: Model Performance Comparison for Glycemic Event Classification

| Model | Prediction Horizon | Hypoglycemia Recall | Euglycemia Recall | Hyperglycemia Recall | Overall Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | 15 minutes | 98% | 91% | 96% | High |

| LSTM | 15 minutes | Lower than LR | Lower than LR | Lower than LR | Moderate |

| ARIMA | 15 minutes | Lowest of all models | Lowest of all models | Lowest of all models | Poor |

| Logistic Regression | 1 hour | Lower than LSTM | Lower than LSTM | Lower than LSTM | Moderate |

| LSTM | 1 hour | 87% | Lower than 15-min | 85% | High |

| ARIMA | 1 hour | Lowest of all models | Lowest of all models | Lowest of all models | Poor |

Clinical Application Analysis

The performance differentials revealed in these comparisons have significant clinical implications. Logistic regression's superior performance at the 15-minute horizon—particularly its 98% recall rate for hypoglycemia—makes it exceptionally valuable for immediate intervention planning. This high sensitivity to impending hypoglycemic events is crucial for preventing acute complications, as missing such events could have serious consequences for patients [1].

In contrast, LSTM's strength at the 1-hour prediction horizon supports longer-term planning, potentially helping patients and clinicians make adjustments to insulin dosing, carbohydrate intake, or physical activity with sufficient lead time. The performance degradation observed in all models as the prediction horizon extends highlights the inherent challenges in glucose forecasting, particularly given the complex physiological processes and external factors affecting glucose dynamics [1] [7].

ARIMA's consistent underperformance across all categories and time horizons suggests it is less suitable for glycemic event classification compared to machine learning approaches. This is likely because ARIMA models are designed for stationary time series and struggle to capture the complex, non-linear relationships that characterize glucose metabolism [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Collection and Preprocessing Standards

The experimental foundation for comparing glycemic prediction models requires rigorous data collection and preprocessing protocols. Research in this domain typically utilizes two primary data sources: real-world clinical cohort studies and in-silico simulations. In a representative study, real patient data was obtained from 11 participants with type 1 diabetes using CGM devices, with data collected at 15-minute intervals. Simultaneously, simulated data was generated using the Simglucose platform (v0.2.1), creating 10 virtual patients across three age groups (adults, adolescents, children) spanning 10 days with randomized meal and snack patterns [1].

Data preprocessing involves several critical steps to ensure data quality and consistency. Raw CGM data typically requires resampling to a consistent 15-minute frequency, handling of missing values through appropriate imputation methods, and filtering of physiologically implausible values. For hypoglycemia classification studies, data is often structured around hypoglycemic events, defined as episodes with registered glucose levels <3.5 mmol/L (<63 mg/dL). For each event, a time series encompassing the preceding and subsequent 6 hours (12 hours total) from the first recorded hypoglycemic level is extracted for analysis [8].

Table 2: Standard Data Preparation Pipeline

| Processing Step | Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Data Harmonization | Downsampling all data to 15-minute intervals | Standardize temporal resolution across different sensors |

| Event Definition | Identifying hypoglycemic events (<70 mg/dL) and extracting 12-hour windows around them | Create consistent analysis units |

| Feature Engineering | Calculating rate of change, variability indices, and time-based features | Enhance predictive signal from raw glucose data |

| Data Splitting | Stratified splitting into training (80%), validation (10%), and test sets (10%) | Ensure robust evaluation and prevent data leakage |

Feature Engineering Strategies

Feature engineering is a critical component in developing effective glycemic classification models. When only glucose data is available—whether due to data collection limitations or patient non-compliance—features extracted from the changes in glucose levels themselves become particularly valuable. These engineered features capture the dynamism and trends in glucose fluctuations, enabling more accurate predictions even without additional physiological metrics [1].

Key feature categories include:

- Rate of change metrics: Short-term and long-term glucose velocity calculated over different windows

- Variability indices: Standard deviation, coefficient of variation, and mean amplitude of glycemic excursion

- Time-based features: Rolling averages, seasonal decompositions, and time-of-day indicators

- Threshold-based features: Percentage of time spent in different glycemic ranges prior to prediction point

For studies incorporating additional data modalities, features might include insulin-on-board calculations, carbohydrate intake timing and quantity, and exercise characteristics (type, duration, intensity). However, research has demonstrated that models built with CGM data alone can achieve statistically indistinguishable performance compared to models using multiple data modalities, highlighting the particular value of carefully engineered glucose-derived features [7].

Model Training and Evaluation Framework

The evaluation of glycemic classification models follows rigorous machine learning protocols. Studies typically employ repeated stratified nested cross-validation to ensure reliable performance estimation and mitigate overfitting. This approach is particularly important given the class imbalance often present in glycemic event data, where hypoglycemic events may be significantly less frequent than euglycemic periods [7].

Performance metrics are selected to provide a comprehensive view of model capabilities:

- Recall (Sensitivity): Particularly crucial for hypoglycemia prediction, where missing events has serious consequences

- Precision: Important for minimizing false alarms that could lead to alert fatigue

- Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC): Provides an aggregate measure of performance across classification thresholds

- Calibration: Assesses how well predicted probabilities match observed frequencies, often measured using Brier scores

For clinical applicability, models must demonstrate not only high discrimination but also excellent calibration. Well-calibrated models ensure that a predicted hypoglycemia probability of 80% corresponds to an actual hypoglycemia occurrence rate of approximately 80%, enabling clinicians and patients to appropriately weigh risks and benefits of interventions [7].

Technical Implementation Guide

Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing effective glycemic classification models requires specific data components and computational resources. The table below details essential "research reagents" for developing logistic regression models for glycemic event prediction.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Glycemic Classification Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Components | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Data Sources | Real-world CGM data (Dexcom G6, Medtronic Guardian), Simulated data (Simglucose, UVA/Padova Simulator) | Provides foundational glucose traces for model development and validation |

| Feature Engineering Tools | Rolling window calculators, Variability indices, Time-based feature extractors | Transforms raw glucose data into predictive features |

| Modeling Frameworks | Scikit-learn (logistic regression), TensorFlow/PyTorch (LSTM), Statsmodels (ARIMA) | Provides algorithmic implementations for model training |

| Evaluation Metrics | Recall, Precision, AUROC, Brier score, Consensus Error Grid analysis | Quantifies model performance and clinical safety |

Comparative Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the structured workflow for developing and comparing glycemic event classification models, from data preparation through performance evaluation:

Advanced Modeling Considerations

Emerging Approaches in Glucose Forecasting

While this guide focuses on logistic regression, LSTM, and ARIMA models, recent research has explored more advanced architectures. Transformer-based models, including PatchTST and Crossformer, have demonstrated remarkable performance in multi-horizon blood glucose prediction. For 30-minute predictions, Crossformer achieved an RMSE of 15.6 mg/dL on the OhioT1DM dataset, while PatchTST excelled at longer-term predictions (1-4 hours) [9].

Additionally, Large Language Model (LLM) frameworks have shown promise in glucose forecasting. The Gluco-LLM framework, leveraging Time-LLM, reportedly achieves a 21.87% reduction in prediction error compared to state-of-the-art models, with 96.19% of predictions falling within clinically acceptable ranges on the Consensus Error Grid [10].

Another emerging approach focuses specifically on classifying the root causes of hypoglycemic events. Purpose-built convolutional neural networks (HypoCNN) have demonstrated strong performance in identifying underlying reasons for hypoglycemia, such as overestimated bolus (27% of cases), overcorrection of hyperglycemia (29%), and excessive basal insulin pressure (44%), achieving an AUC of 0.917 on ground-truth validation [8].

Practical Implementation Challenges

Translating glycemic classification models from research to clinical practice faces several significant challenges. The "black box" nature of complex models like LSTM and transformer networks can limit clinical trust and adoption, as clinicians and patients may struggle to understand or trust recommendations without transparent reasoning [11].

Data quality and availability present additional hurdles. While studies have shown that models using CGM data alone can achieve excellent performance for exercise-related glycemic events (AUROCs ranging from 0.880 to 0.992), real-world implementation must contend with missing data, sensor errors, and compression artifacts [7].

Furthermore, model performance can vary across different patient subgroups and clinical contexts. Performance degradation may occur when models trained on general populations are applied to specific scenarios like exercise conditions or critical care settings. In septic patients, for instance, unique glucose dynamics due to stress hyperglycemia may require specialized modeling approaches [12].

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that model selection for glycemic event classification depends critically on the specific clinical requirements and prediction horizon. Logistic regression emerges as the superior choice for short-term (15-minute) predictions, particularly with its exceptional recall for hypoglycemia events. LSTM networks show strength for longer-term (1-hour) forecasting, while ARIMA models consistently underperform for classification tasks.

For clinical implementation, researchers should consider the trade-off between model complexity and interpretability. While more complex models may offer marginal performance gains in some scenarios, logistic regression provides an compelling combination of high performance, computational efficiency, and interpretability—particularly valuable in clinical settings where understanding model reasoning is as important as prediction accuracy itself.

Future directions in glycemic event classification will likely involve hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of multiple models, ensemble methods that improve robustness, and explainable AI techniques that enhance clinical trust and adoption. As these technologies evolve, probabilistic classification models will play an increasingly important role in creating personalized, adaptive diabetes management systems.

Accurate prediction of blood glucose levels is a cornerstone of modern diabetes management, enabling proactive interventions to prevent dangerous hypoglycemic and hyperglycemic events. Within the field of predictive modeling, three distinct approaches have emerged as prominent solutions: traditional statistical models like the Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA), conventional machine learning algorithms such as Logistic Regression, and advanced deep learning architectures, particularly Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks. Each paradigm offers different capabilities for handling the complex, time-dependent nature of glucose dynamics. LSTMs, a specialized form of recurrent neural network, are uniquely designed to capture long-range temporal dependencies, making them exceptionally suitable for modeling the physiological patterns in glucose data. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these models, focusing on their predictive performance, implementation requirements, and suitability for real-world clinical and research applications.

Performance Comparison at a Glance

The table below summarizes the key performance metrics of LSTM, ARIMA, and Logistic Regression models as reported in recent studies, providing a high-level overview of their capabilities for glucose level prediction.

Table 1: Overall Model Performance for Glucose Prediction

| Model | Best Prediction Horizon | Key Strengths | Reported Performance (Recall/RMSE) | Primary Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | 60 minutes [1] | Captures complex temporal patterns; handles multivariate data [13] | 87% (Hypo/Hyperglycemia, 1-Hour) [1]; RMSE: 20.50 ± 5.66 mg/dL (Aggregated) [13] | Ideal for medium-term forecasting and proactive insulin dosing in artificial pancreas systems. |

| Logistic Regression | 15 minutes [1] | High speed and interpretability; effective for short-term classification [1] | 98% (Hypoglycemia, 15-Min) [1] | Excellent for real-time, short-term alerts for imminent hypoglycemia. |

| ARIMA | Varies | Statistical robustness; efficient for univariate, stationary series [14] [15] | Outperformed by LSTM and Ridge Regression [15] | Serves as a baseline model; most effective when glucose trends are stable and linear. |

A more detailed quantitative comparison across different prediction horizons and metrics reveals the nuanced performance profile of each model.

Table 2: Detailed Quantitative Performance Comparison

| Model | Prediction Horizon | Performance Metric | Result | Dataset / Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | 60 minutes | Recall (Hypo/Hyperglycemia) | 85%, 87% [1] | Real patient CGM data [1] |

| 60 minutes | RMSE (Aggregated Training) | 20.50 ± 5.66 mg/dL [13] | HUPA UCM Dataset (25 subjects) [13] | |

| 60 minutes | RMSE (Individual Training) | 22.52 ± 6.38 mg/dL [13] | HUPA UCM Dataset (25 subjects) [13] | |

| 30 & 60 minutes | RMSE | 6.45 & 17.24 mg/dL [16] | OhioT1DM Dataset [16] | |

| Logistic Regression | 15 minutes | Recall (Hypoglycemia) | 98% [1] | Real patient CGM data [1] |

| 15 minutes | Recall (Euglycemia/Hyperglycemia) | 91%, 96% [1] | Real patient CGM data [1] | |

| ARIMA | 15 minutes & 1 hour | Recall (Hypo/Hyperglycemia) | Underperformed LSTM & Logistic Regression [1] | Real patient CGM data [1] |

| 30 minutes | RMSE | Outperformed by Ridge Regression [15] | OhioT1DM Dataset [15] |

Experimental Protocols and Model Methodologies

LSTM Model Implementation

Architecture and Training: A common implementation for glucose forecasting uses a sequence-to-sequence architecture. The model takes an input sequence of past data—typically a 180-minute window (36 time steps at 5-minute intervals)—including features like blood glucose levels, carbohydrate intake, bolus insulin, and basal insulin rate. This sequence is processed by an LSTM layer (e.g., with 50 hidden units) followed by fully connected dense layers. The model is trained to output a sequence of future glucose values, such as the next 60 minutes (12 time steps) [13]. The training often employs a walk-forward rolling forecast approach, mirroring real-world deployment where the model updates its predictions as new CGM readings arrive [13]. The Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001 and Mean Squared Error (MSE) as the loss function are standard choices [13].

Personalized vs. Aggregated Training: A critical methodological consideration is the training strategy. Individualized models are trained on a single subject's data, tailoring the parameters to that person's unique physiology. In contrast, aggregated models are trained on a combined dataset from multiple subjects. Research indicates that individualized LSTM models can achieve accuracy comparable to aggregated models (RMSE of 22.52 vs. 20.50 mg/dL) despite using less data, highlighting their data efficiency and potential for privacy-preserving, on-device learning [13].

Competing Model Protocols

Logistic Regression is typically implemented as a classification task, predicting glucose levels categorized into hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL), euglycemia (70–180 mg/dL), and hyperglycemia (>180 mg/dL). The model is trained on engineered features from CGM data, such as rolling averages and rate-of-change metrics [1].

ARIMA, a univariate statistical model, relies solely on past glucose values. The model order parameters (p, d, q) are determined for each subject via grid search, often guided by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), to account for individual time-series characteristics [15]. Its performance is often benchmarked against naive baselines like the persistence model (forecast equals the last observed value) [15].

Workflow and Architectural Diagrams

LSTM for Glucose Prediction Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow for developing and deploying an LSTM model for blood glucose prediction, from data collection to clinical application.

LSTM Model Architecture

The core LSTM architecture for processing sequential glucose data is detailed in the diagram below. It shows how the model handles input sequences to generate future predictions.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| OhioT1DM Dataset | Public benchmark dataset for training and evaluating glucose prediction models. | Contains CGM, insulin, carbohydrate, and activity data from 12 people with T1D [16] [15]. |

| HUPA UCM Dataset | A dataset for researching diabetes management under free-living conditions. | Includes CGM, insulin, carbs, and lifestyle metrics from 25 individuals [13]. |

| CGM Simulator (Simglucose) | In-silico platform for generating synthetic patient data and testing algorithms. | Python implementation of the FDA-approved UVA/Padova T1D Simulator [1]. |

| Deep Learning Framework (Keras) | High-level API for rapid prototyping and training of LSTM models. | Used with Python and TensorFlow backend for model development [13]. |

| Clarke Error Grid Analysis | Clinical validation tool to assess the clinical accuracy of glucose predictions. | Zones A (clinically accurate) and B (benign errors) are target regions [17]. |

The comparative analysis indicates a clear trade-off between model complexity, interpretability, and performance across different prediction horizons. LSTM networks demonstrate superior performance for medium-term forecasts (60 minutes), making them the most suitable backbone for advanced applications like automated insulin delivery. Their ability to learn complex, non-linear temporal patterns from multivariate data is a significant advantage, though it comes at the cost of computational complexity and data requirements [13] [1].

In contrast, Logistic Regression excels as a highly efficient and interpretable model for very short-term (15-minute) classification of glycemic events, particularly for hypoglycemia warning systems [1]. ARIMA provides a statistically sound baseline but is generally outperformed by both machine learning and deep learning alternatives in handling the noisy and complex nature of real-world glucose data [1] [15].

Future research is poised to enhance LSTM frameworks further through hybrid architectures (e.g., Transformer-LSTM) [17], personalized federated learning to improve accuracy while preserving data privacy [5] [18], and advanced loss functions that specifically target the high-risk hypoglycemic and hyperglycemic ranges [5]. This evolution will continue to solidify the role of deep learning in creating safer and more effective personalized diabetes management systems.

The accurate prediction of glucose levels is a critical component of modern diabetes management, enabling proactive interventions to prevent dangerous hypoglycemic and hyperglycemic events. Within this field, a key research thesis has emerged, focusing on the comparative performance of traditional statistical models, like the Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA), against machine learning approaches such as logistic regression and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks. While complex deep learning models often show impressive results, ARIMA remains a fundamentally important tool in the researcher's toolkit. This guide provides an objective comparison of these model types, detailing their performance, underlying methodologies, and appropriate applications to help researchers and drug development professionals select the optimal predictive tool for their specific clinical or investigative context.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure a fair comparison, researchers typically employ standardized experimental protocols. The following workflows and methodologies are common in studies comparing ARIMA, LSTM, and logistic regression for glucose forecasting.

Standardized Experimental Workflow

The experimental process for developing and validating glucose prediction models follows a systematic sequence from data acquisition to final model evaluation. The diagram below outlines this standard workflow.

Core Methodological Components

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The OhioT1DM dataset is a publicly available benchmark containing data from individuals with Type 1 Diabetes, often resampled at 5 or 15-minute intervals [10] [15]. Standard preprocessing involves addressing data gaps through linear interpolation for short periods (e.g., ≤30 minutes) and chronological splitting into training, validation, and test sets to prevent data leakage [15] [1]. A rolling-origin evaluation protocol is frequently used to simulate real-world deployment, where models are repeatedly trained on historical data and tested on subsequent unseen points [15].

Feature Engineering Strategies

Feature engineering is crucial, particularly for non-ARIMA models. For logistic regression and LSTM, common engineered features from CGM time series include [1] [19]:

- Lag Features: Glucose values from preceding time points (e.g., t-1, t-2, ..., t-12 for a 60-minute history at 5-minute resolution).

- Rate-of-Change (ROC): The speed of glucose change, often calculated over the past 15-30 minutes.

- Moving Averages & Variability Indices: Short-term averages (e.g., 15-minute) and standard deviations to capture trends and stability.

ARIMA models, in contrast, typically use the raw time series of past glucose values, relying on their inherent autoregressive structure [15].

Model Specification and Training

- ARIMA (Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Average): For each subject, a univariate ARIMA model is fitted to their CGM series. The order parameters (p, d, q) are selected via grid search, often guided by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) [15]. The model's core assumption is that future glucose values are a linear function of past values and past forecast errors.

- Logistic Regression: This model is used for classifying future glucose into ranges (e.g., hypo-/hyperglycemia). It is trained on the engineered features (lags, ROC) with regularization to prevent overfitting [1] [19].

- LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory): A type of recurrent neural network designed to capture long-term temporal dependencies. It processes sequences of past glucose data (and optionally other features) to predict either a future glucose value (regression) or its class (classification) [1] [19].

Comparative Performance Data

The performance of ARIMA, LSTM, and logistic regression models varies significantly depending on the prediction horizon and the specific glycemic range of interest. The following tables synthesize quantitative findings from recent comparative studies.

Table 1: Model Performance for 15-Minute Prediction Horizon (Classification Task)

| Glucose Range | Metric | ARIMA | Logistic Regression | LSTM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL) | Recall | Lower [1] | 98% [19] | 88% [19] |

| Euglycemia (70-180 mg/dL) | Recall | Lower [1] | 91% [1] | Lower than Logistic Regression [1] |

| Hyperglycemia (>180 mg/dL) | Recall | Lower [1] | 96% [1] | Lower than Logistic Regression [1] |

Table 2: Model Performance for 60-Minute Prediction Horizon (Classification Task)

| Glucose Range | Metric | ARIMA | Logistic Regression | LSTM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL) | Recall | 7.3% [19] | 83% [19] | 87% [19] |

| Hyperglycemia (>180 mg/dL) | Recall | ~60% [19] | Lower than LSTM [1] | 85% [19] |

Table 3: Model Performance for Numerical Glucose Forecasting (Regression Task)

| Model | Context / Metric | Performance |

|---|---|---|

| ARIMA | RMSE for Glucose Prediction [20] | 71.7% lower RMSE than LSTM in one study [20] |

| Ridge Regression | RMSE for 30-min forecast vs. ARIMA [15] | Outperformed ARIMA (Significant reduction in RMSE) [15] |

| LSTM | General regression on complex datasets | Can be outperformed by simpler models on linear/short-term tasks [20] [21] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Resources for Glucose Prediction Research

| Resource / Solution | Specification / Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| OhioT1DM Dataset | Public benchmark dataset with CGM, insulin, and carbohydrate data from people with T1D. | Model training, benchmarking, and comparative validation [10] [15]. |

| CGM Simulator | Software (e.g., Simglucose) for generating in-silico CGM data for controlled testing. | Initial algorithm testing and validation across virtual patient cohorts [1] [19]. |

| Rolling-Origin Validation Framework | A robust evaluation protocol that simulates real-time forecasting by expanding the training window. | Prevents over-optimistic performance estimates and tests model robustness [15]. |

| Clarke Error Grid Analysis (CEG) | A clinical accuracy assessment tool that categorizes prediction errors based on clinical risk. | Validates the clinical acceptability of model predictions beyond statistical error [15]. |

| Feature Engineering Pipeline | Computational tools for generating lag, rate-of-change, and variability features from raw CGM data. | Essential for preparing inputs for logistic regression and LSTM models [1]. |

Discussion and Comparative Analysis

Model Selection Framework

The experimental data reveals that no single model is universally superior. The optimal choice is a function of the specific prediction horizon and the clinical objective. The following diagram synthesizes the decision-making logic for model selection.

Interpretation of Comparative Results

The performance data underscores a clear trade-off. Logistic Regression excels at short-horizon classification, making it ideal for applications requiring immediate alerts for impending hypoglycemia, where high recall is critical for patient safety [1] [19]. Its strength lies in leveraging simple, engineered features like the recent rate of change.

In contrast, LSTM models demonstrate superior capability for long-horizon predictions (e.g., 60 minutes). Their complex architecture is better suited to modeling the non-linear physiological processes that influence glucose levels over longer periods, making them more reliable for predicting both hyper- and hypoglycemic events further in advance [1] [19].

The performance of ARIMA is more context-dependent. While it can be outperformed by more complex models, particularly on classification tasks [1], it remains a potent tool. It can achieve excellent results in numerical forecasting, sometimes surpassing LSTM, especially when relationships are primarily linear or datasets are limited [20] [21]. Its key advantages are computational efficiency and strong performance for short-term numerical predictions, making it a viable candidate for resource-constrained or embedded systems [15].

The research-driven comparison between ARIMA, logistic regression, and LSTM confirms that the landscape of glucose prediction is not one of outright winners and losers. ARIMA models maintain significant relevance, particularly for short-term numerical forecasting and in settings where computational efficiency and interpretability are valued. Logistic regression is the specialist for imminent classification tasks, while LSTMs are the powerhouse for long-term forecasting. The findings indicate that the future of glucose prediction may not lie in a single model, but in hybrid approaches that leverage the distinct strengths of each to achieve robust, accurate, and clinically actionable forecasting systems.

The accurate prediction of blood glucose levels is paramount for improving the management of diabetes, a chronic disease affecting a significant portion of the global adult population [22]. Predictive models can provide early warnings for hypoglycemic (low blood glucose) or hyperglycemic (high blood glucose) events, enabling timely interventions. However, the reliability of these models is contingent upon the use of robust evaluation metrics that can adequately capture their clinical utility. Evaluation metrics are quantitative measures used to assess the performance and effectiveness of a statistical or machine learning model [23]. The choice of metric is critical, as it determines how model performance is quantified and compared.

This guide focuses on a suite of essential metrics for evaluating regression and classification models, particularly within the context of a broader study comparing the glucose prediction accuracy of three distinct models: Logistic Regression, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, and the Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) model. While regression metrics like RMSE and MAE assess the precision of continuous glucose value predictions, classification metrics such as AUC and clinical accuracy measures (e.g., precision, recall) evaluate the model's ability to correctly categorize glucose states (e.g., hypo-, normo-, or hyperglycemia) [1] [22]. A comprehensive understanding of these metrics allows researchers to select the most appropriate model for a given clinical application, whether the priority is short-term tactical alerts or long-term strategic management.

Defining the Core Evaluation Metrics

Metrics for Continuous Value Prediction (Regression)

When the goal of a model is to forecast a continuous blood glucose value (in mg/dL or mmol/L), regression metrics are used. These metrics quantify the difference between the predicted and the actual measured values.

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE): RMSE is the square root of the average squared differences between predicted and actual values [24] [25]. It is calculated as: ( \operatorname{RMSE} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N} \sum{j=1}^{N}\left(y{j}-\hat{y}{j}\right)^{2}} ) where (yj) is the actual value, (\hat{y}_j) is the predicted value, and (N) is the number of observations [26] [24]. As squaring emphasizes larger errors, RMSE is sensitive to outliers and is most appropriate when large errors are particularly undesirable [24] [25]. A perfect model has an RMSE of 0.

Mean Absolute Error (MAE): MAE calculates the average of the absolute differences between predicted and actual values [26] [25]. It is calculated as: ( \operatorname{MAE} = \frac{1}{N} \sum{j=1}^{N}\left|y{j}-\hat{y}_{j}\right| ) MAE provides a linear score, meaning all errors are weighted equally. This makes it more robust to outliers than RMSE and gives a clearer view of the model's typical prediction accuracy [24] [27]. Like RMSE, its value is in the units of the target variable, and an ideal value is 0.

Comparative Properties of RMSE and MAE: The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these two primary regression metrics.

Table 1: Comparison of Regression Metrics RMSE and MAE

| Property | Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity to Outliers | High (penalizes large errors heavily) [24] | Low (treats all errors equally) [24] |

| Interpretation | Error in original data units, but skewed by large errors | Easy to understand; average error in original units [27] |

| Optimal Predictor | Predicts the mean of the target distribution [25] | Predicts the median of the target distribution [25] |

| Best Use Case | When large errors are especially unacceptable | When the cost of an error is proportional to its size |

Metrics for Class-Based Prediction (Classification)

In many clinical scenarios, predicting the exact glucose value is less critical than correctly classifying the patient's state into a relevant category, such as hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL), euglycemia (70-180 mg/dL), or hyperglycemia (>180 mg/dL) [1]. For these tasks, classification metrics are used, which are derived from a confusion matrix.

Confusion Matrix: A confusion matrix is an N x N table (where N is the number of classes) that summarizes the performance of a classification model by comparing the actual labels to the predicted labels [26] [23]. For binary classification, it contains four key elements:

- True Positives (TP): The model correctly predicts the positive class.

- True Negatives (TN): The model correctly predicts the negative class.

- False Positives (FP): The model incorrectly predicts the positive class (Type I error).

- False Negatives (FN): The model incorrectly predicts the negative class (Type II error) [26] [28].

Precision, Recall, and F1-Score: From the confusion matrix, several crucial metrics can be derived:

- Precision (Positive Predictive Value): Measures the accuracy of positive predictions. ( \text{Precision} = \frac{TP}{TP + FP} ) [26] [27]. High precision is vital when the cost of a false positive is high (e.g., triggering an unnecessary insulin dose).

- Recall (Sensitivity): Measures the model's ability to identify all actual positive cases. ( \text{Recall} = \frac{TP}{TP + FN} ) [26] [27]. High recall is critical when missing a positive event is dangerous (e.g., failing to predict a hypoglycemic episode).

- F1-Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single metric that balances both concerns. ( \text{F1 Score} = 2 \times \frac{\text{Precision} \times \text{Recall}}{\text{Precision} + \text{Recall}} ) [26] [23]. It is especially useful with imbalanced datasets.

Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC-ROC): The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve is a graphical plot that illustrates the diagnostic ability of a binary classifier by plotting the True Positive Rate (Recall) against the False Positive Rate (1 - Specificity) at various threshold settings [26] [23]. The Area Under this Curve (AUC) summarizes the model's ability to distinguish between classes. An AUC of 1.0 represents a perfect model, while 0.5 represents a model no better than random guessing [27] [23]. AUC is valuable because it is independent of the classification threshold and the class distribution, making it excellent for model comparison [23].

Figure 1: A decision workflow for selecting the most appropriate evaluation metric based on model output and clinical priority.

Experimental Comparison: Logistic Regression vs. LSTM vs. ARIMA

Recent research has directly compared the performance of Logistic Regression, LSTM, and ARIMA models for predicting glucose levels, using the metrics defined above. The experimental protocols and their results provide critical insights for model selection.

A 2023 study evaluated these three models for predicting hypoglycemia, euglycemia, and hyperglycemia classes 15 minutes and 1 hour ahead [1]. The data was sourced from two primary avenues:

- Clinical Cohort Data: Real patient data was acquired from a study involving participants with type 1 diabetes who used a continuous glucose monitor (CGM). This data included sensor glucose readings, insulin dosing, and carbohydrate intake [1].

- In-Silico Simulation: Data was also generated using the CGM Simulator (Simglucose v0.2.1), a Python implementation of the UVA/Padova T1D Simulator. This simulator created a large cohort of virtual patients across different age groups, simulating glucose dynamics over multiple days with randomized meal and snack schedules [1].

The raw data was pre-processed to a consistent 15-minute frequency. The core of the methodology involved feature engineering, where additional predictive factors were derived from the raw CGM time series. These included rolling averages, rate-of-change metrics, and variability indices, which helped the models capture the dynamism of glucose fluctuations [1]. The models were then trained and evaluated, with their performance compared using precision, recall, and accuracy.

Quantitative Performance Results

The experimental results revealed that no single model was superior across all prediction horizons, highlighting a trade-off between short-term and mid-term accuracy.

Table 2: Model Performance in Glucose Level Classification (Recall Rates) [1]

| Glucose Class | Prediction Horizon | Logistic Regression | LSTM | ARIMA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperglycemia | 15 minutes | 96% | (Lower than LR) | (Lowest) |

| (>180 mg/dL) | 1 hour | (Lower than LSTM) | 85% | (Lowest) |

| Euglycemia | 15 minutes | 91% | (Lower than LR) | (Lowest) |

| (70-180 mg/dL) | 1 hour | (Data not specified) | (Data not specified) | (Lowest) |

| Hypoglycemia | 15 minutes | 98% | (Lower than LR) | (Lowest) |

| (<70 mg/dL) | 1 hour | (Lower than LSTM) | 87% | (Lowest) |

For continuous glucose value prediction, another study focusing on non-invasive monitoring found that the ARIMA model could outperform LSTM on their specific dataset, achieving a 71.7% lower RMSE for glucose prediction [20]. This contrasts with the classification-focused study and underscores that the optimal model can depend heavily on the task (classification vs. regression), data characteristics, and prediction horizon.

Analysis and Model Selection Guidelines

The data from these experiments allows for a direct, objective comparison of the three models:

- Logistic Regression demonstrated exceptional performance for short-term (15-minute) classification, achieving the highest recall rates for all glycemia classes [1]. This suggests it is highly effective for immediate, tactical alerts where correctly identifying an impending event is the priority. Its strength lies in its simplicity and efficiency with smaller, engineered features.

- LSTM Networks proved to be the best model for longer-term (1-hour) classification, outperforming logistic regression for hyper- and hypoglycemia prediction [1]. As a type of recurrent neural network, LSTM's ability to capture long-term dependencies and complex temporal patterns in sequential data makes it more suited for forecasting further into the future.

- ARIMA, a classic statistical time-series model, generally underperformed the machine learning models in the classification task [1]. However, its strong performance in the regression-based study [20] indicates it remains a viable and sometimes superior candidate, particularly when the dataset or forecasting task aligns with its underlying assumptions.

Figure 2: A comparative analysis of the strengths and limitations of Logistic Regression, LSTM, and ARIMA models based on experimental results in glucose prediction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

To conduct rigorous experiments in glucose prediction modeling, researchers rely on a combination of data, software, and evaluation frameworks. The following table details key components used in the featured studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Glucose Prediction Research

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) Data | Data Source | Provides real-time, high-frequency time-series data of interstitial glucose levels; the foundational input for training and testing predictive models [1] [22]. |

| In-Silico Simulator (e.g., Simglucose) | Software / Data Source | Generates synthetic data for a large cohort of virtual patients; useful for initial algorithm testing and controlling variables, though may lack real-world complexity [1]. |

| Lifestyle Log (Carb/Insulin) | Data Source | Records carbohydrate intake and insulin dosing; provides crucial contextual features that significantly improve prediction accuracy [1] [22]. |

| Python with Scikit-learn & Keras/TensorFlow | Software | Primary programming environment; provides libraries for data preprocessing (e.g., pandas), implementing models (Logistic Regression, LSTM), and calculating metrics (e.g., scikit-learn.metrics) [24] [28]. |

| Confusion Matrix Analysis | Evaluation Framework | The foundational table for calculating classification metrics like Precision, Recall, and F1-Score, enabling detailed error analysis [1] [23]. |

| ROC Curve Analysis | Evaluation Framework | A graphical and quantitative method (via AUC) to evaluate a classification model's performance across all possible thresholds, independent of class distribution [29] [23]. |

Model Deployment in Practice: Methodological Approaches and Clinical Use Cases

Data Requirements and Preprocessing for Each Model Architecture

In the rapidly evolving field of diabetes management, accurate glucose prediction is paramount for preventing acute complications and long-term health deterioration. The performance of any predictive model is intrinsically tied to the quality and structure of its training data, with different model architectures demanding distinct preprocessing approaches and exhibiting varying capabilities in handling real-world clinical data challenges. This guide provides a systematic comparison of three prominent model architectures—Logistic Regression, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, and AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA)—focusing on their data requirements, preprocessing methodologies, and empirical performance in glucose prediction tasks. Understanding these foundational differences enables researchers and clinicians to select appropriate modeling strategies based on available data resources and clinical objectives, ultimately advancing personalized diabetes care through more reliable forecasting systems.

Model-Specific Data Requirements and Preprocessing Techniques

Logistic Regression

Data Requirements: Logistic Regression operates under strict statistical assumptions that dictate specific data requirements. The model assumes independent observations, meaning there should be no correlation or dependence between input samples in the dataset [30]. It requires a binary dependent variable, typically representing glucose classification outcomes such as hypoglycemic/hyperglycemic events versus normal ranges. The model further assumes a linear relationship between independent variables and the log odds of the dependent variable, necessitating careful feature engineering to satisfy this condition [30]. The dataset should not contain extreme outliers as they can distort coefficient estimation, and sufficient sample size is crucial for producing reliable, stable results.

Preprocessing Workflow: The preprocessing pipeline for Logistic Regression begins with comprehensive data exploration to identify missing values, incorrect data types, and inconsistent categories [31]. For missing values in numeric features, imputation with mean or median values is recommended depending on the distribution, while categorical features should be filled with the most frequent category [31]. Outlier detection and treatment using statistical methods like z-scores or interquartile range is essential to prevent coefficient distortion. Categorical variables require appropriate encoding strategies—label encoding for ordered categories and one-hot encoding for unordered categories [31]. Feature scaling through standardization (zero mean, unit variance) or normalization (0-1 range) is critical for algorithms relying on gradient descent, with the choice depending on the specific implementation. Finally, the dataset must be split into training and testing sets, typically 70-80% for training and 20-30% for testing, with an optional validation set for hyperparameter tuning [31].

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Networks

Data Requirements: LSTM networks excel at processing sequential data with temporal dependencies, making them particularly suitable for continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) data streams. Unlike Logistic Regression, LSTMs can effectively handle multivariate time-series inputs, incorporating additional physiological parameters such as carbohydrate intake, insulin administration (both basal and bolus), physical activity, and heart rate [13]. The model requires substantial temporal continuity with consistent sampling intervals (e.g., 5-minute readings from CGM devices) to effectively capture metabolic patterns [13]. For individualized training approaches, data from individual subjects is sufficient, while aggregated models benefit from combined datasets across multiple patients to capture population-level trends [13].

Preprocessing Workflow: LSTM preprocessing begins with comprehensive data cleaning to address sensor artifacts, missing CGM values, and physiological implausibilities using domain-specific filters [13]. For free-living data, additional preprocessing may include synchronizing timestamps across different data sources (CGM, insulin pumps, activity trackers) and handling irregularly sampled events like meal intake. The critical transformation involves restructuring the temporal data into supervised learning format through sliding window approaches, where past sequences (typically 180 minutes or 36 time steps at 5-minute intervals) are used to predict future glucose values (e.g., 60 minutes ahead) [13]. Feature scaling through normalization (0-1 range) is essential to ensure stable gradient flow during training. For multivariate predictions, all input features (glucose, carbohydrates, insulin) must undergo simultaneous normalization. The dataset should be split chronologically (not randomly) into training, validation, and test sets (e.g., 60:20:20 ratio) to preserve temporal relationships and enable realistic evaluation [32].

ARIMA (AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average)

Data Requirements: ARIMA models have one fundamental requirement: stationarity [33]. A stationary time series maintains stable statistical properties (mean, variance, autocorrelation) over time, unlike raw glucose data that typically exhibits trends (progressive changes) and seasonality (recurring patterns). The model works exclusively with univariate data, meaning it processes only historical glucose values without incorporating external variables like insulin or carbohydrate intake [33]. While ARIMA can handle missing values through interpolation, substantial data gaps compromise model reliability. The integrated (I) component specifically addresses non-stationarity through differencing operations, transforming the raw series into one with stable statistical properties suitable for autoregressive modeling.

Preprocessing Workflow: The ARIMA preprocessing pipeline focuses intensely on achieving stationarity. The process begins with visual inspection of the glucose series to identify evident trends and seasonal patterns [33]. Statistical tests including the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test and Kwiatkowski-Phillips-Schmidt-Shin (KPSS) test provide quantitative assessment of stationarity [33]. For non-stationary series, differencing is applied where each value is replaced by the change between successive periods (Y't = Yt - Yt-1) to remove linear trends [33]. Seasonal differencing (e.g., subtracting the value from 24 hours prior for daily patterns) addresses periodic fluctuations. The appropriate differencing order (d parameter) is determined iteratively until stationarity is achieved. After model fitting, residual analysis confirms whether the transformed series exhibits the white noise properties indicative of successful stationarization. Unlike LSTM, ARIMA typically does not require feature scaling as its estimation procedures are scale-invariant.

Table 1: Comparative Data Requirements for Glucose Prediction Models

| Parameter | Logistic Regression | LSTM | ARIMA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Type | Tabular (IID) | Sequential time-series | Univariate time-series |

| Temporal Dependencies | Not supported | Essential requirement | Fundamental aspect |

| Variable Support | Multivariate | Multivariate | Univariate only |

| Stationarity Requirement | Not applicable | Not required | Mandatory |

| Minimum Data Volume | Large sample size | Moderate to large | Smaller series acceptable |

| Handling Missing Data | Imputation required | Imputation or masking | Interpolation or omission |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Comparison

Experimental Designs in Current Literature

Individualized vs. Aggregated LSTM Training: A recent investigation compared two LSTM training strategies using the HUPA UCM dataset containing CGM values, insulin delivery, and carbohydrate intake from 25 T1D subjects [13]. For individualized training, 25 separate LSTM models were trained independently on each subject's data. The aggregated approach trained a single model on combined data from all subjects. The model architecture maintained consistency with a 180-minute input window (36 time steps at 5-minute intervals) predicting 60 minutes ahead, using LSTM layers with 50 hidden units, and mean squared error as the loss function [13].

ARIMA vs. LSTM for Non-invasive Monitoring: Another study developed a non-invasive glucose and cholesterol monitoring system using NIR sensors, comparing ARIMA and LSTM forecasting performance [20]. Data collected from patients over one month was used to train both models, with evaluation based on Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). The research specifically aimed to address the inconvenience of traditional blood tests that often leads to delayed testing and monitoring [20].

Comprehensive Model Benchmarking: A larger-scale comparison evaluated Transformer-VAE, LSTM, GRU, and ARIMA models for diabetes burden forecasting using Global Burden of Disease data from 1990-2021 [14]. Models were trained on 1990-2014 data and evaluated on 2015-2021 data, with performance measured using Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and RMSE. Robustness was assessed through introduced noise and missing data, while computational efficiency was evaluated based on training time, inference speed, and memory usage [14].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics Across Model Architectures

| Model Architecture | Application Context | Performance Metrics | Comparative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| ARIMA | Non-invasive glucose forecasting | RMSE: ~71.7% lower than LSTM for glucose [20] | Surpassed LSTM in non-invasive prediction [20] |

| LSTM (Individualized) | Blood glucose prediction (T1D) | RMSE: 22.52 ± 6.38 mg/dL; Clarke Zone A: 84.07 ± 6.66% [13] | Comparable to aggregated training despite less data [13] |

| LSTM (Aggregated) | Blood glucose prediction (T1D) | RMSE: 20.50 ± 5.66 mg/dL; Clarke Zone A: 85.09 ± 5.34% [13] | Modest performance improvement over individualized [13] |

| ARIMA | Diabetes burden forecasting | Limited long-term trend capability [14] | Resource-efficient but less accurate for complex trends [14] |

| LSTM | Diabetes burden forecasting | Effective for short-term patterns; long-term dependency challenges [14] | Balanced performance but computational demands [14] |

| Transformer-VAE | Diabetes burden forecasting | MAE: 0.425; RMSE: 0.501; Superior noise resilience [14] | Highest accuracy but computational cost and interpretability challenges [14] |

Strengths and Limitations in Clinical Implementation

Logistic Regression offers high interpretability and computational efficiency, making it suitable for classification tasks like hypoglycemia risk stratification. However, its inability to capture temporal patterns and strict assumptions about feature relationships limit its application for continuous glucose forecasting [30].

LSTM Networks excel at capturing complex temporal dependencies in multivariate physiological data, enabling personalized forecasting that adapts to individual metabolic patterns [13]. The architecture's ability to incorporate multiple input signals (glucose, insulin, carbohydrates, activity) aligns well with the multifactorial nature of glucose regulation. Challenges include substantial computational requirements, need for extensive hyperparameter tuning, and limited interpretability ("black-box" characterization) [34] [14].

ARIMA Models provide statistical rigor and interpretability with clearly defined components representing different aspects of the time series structure [33]. Their computational efficiency facilitates deployment in resource-constrained environments. The critical limitation for glucose forecasting is the univariate nature, preventing incorporation of important external factors like insulin dosing, meal intake, or physical activity [14]. The stationarity requirement also poses challenges for glucose data exhibiting diurnal patterns and physiological trends.

Visualization of Preprocessing Workflows

Data Preprocessing Pipeline for Time-Series Models

LSTM and ARIMA Preprocessing Workflow

Model Selection Decision Framework

Model Selection Based on Data Characteristics

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Glucose Prediction Research

Table 3: Key Research Datasets and Computational Tools

| Resource | Type | Primary Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| HUPA UCM Dataset | Clinical dataset | LSTM glucose prediction [13] | CGM, insulin, carbs, activity from 25 T1D subjects |

| OhioT1DM Dataset | Clinical dataset | LLM-powered glucose prediction [10] | Multi-modal physiological data for personalized forecasting |

| Global Burden of Disease Data | Epidemiological dataset | Diabetes burden forecasting [14] | DALYs, deaths, prevalence (1990-2021) for model benchmarking |

| statsmodels (Python) | Statistical library | ARIMA implementation [33] | Stationarity tests, model fitting, diagnostic plots |

| Keras/TensorFlow | Deep learning framework | LSTM development [13] | Neural network API with LSTM layers, sequence processing |

| scikit-learn | Machine learning library | Logistic Regression preprocessing [31] | Data preprocessing, feature scaling, model evaluation |

| Clarke Error Grid Analysis | Validation methodology | Clinical accuracy assessment [13] | Zone-based classification of prediction clinical accuracy |

The selection of an appropriate model architecture for glucose prediction depends fundamentally on the nature and scope of available data, with each approach offering distinct advantages for specific clinical scenarios. Logistic Regression provides interpretable classification for risk stratification but lacks temporal modeling capabilities. LSTM networks offer powerful multivariate sequence modeling suitable for personalized forecasting incorporating multiple physiological signals, though with substantial computational demands and complexity. ARIMA models deliver statistically rigorous univariate forecasting with computational efficiency but cannot incorporate external factors that significantly influence glucose variability. Contemporary research demonstrates promising directions including hybrid modeling approaches, individualized LSTM training for privacy-preserving applications, and emerging architectures like Transformer-VAE that balance accuracy with robustness to noisy clinical data. As diabetes management increasingly leverages automated insulin delivery systems, the strategic alignment of model architecture with data characteristics and clinical requirements will remain essential for developing reliable, clinically actionable glucose prediction technologies.

The accurate prediction of blood glucose (BG) levels is a cornerstone for advancing type 1 diabetes (T1D) management, particularly in free-living conditions where individuals engage in daily activities like exercise. Reliable forecasting enables proactive interventions to prevent hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia, thereby improving quality of life and reducing long-term complications. Within this field, a critical research focus is the comparative performance of different algorithmic approaches. This guide provides an objective comparison of three prominent models—Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, Logistic Regression, and the Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) model—framed within the broader thesis of evaluating their glucose prediction accuracy for T1D. We summarize experimental data, detail methodologies, and provide resources to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Model Performance Comparison in Free-Living Conditions

The performance of predictive models is typically evaluated using metrics such as Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) for regression tasks (predicting a specific glucose value) and precision/recall for classification tasks (predicting a glycemic state: hypo-, normo-, or hyperglycemia). The tables below synthesize quantitative findings from recent studies conducted in free-living settings.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of LSTM, Logistic Regression, and ARIMA for Glucose Prediction

| Model | Prediction Horizon | Key Performance Metrics | Context & Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM [1] [35] | 15 minutes | RMSE: ~0.43 mmol/L (~7.74 mg/dL) [36] | Free-living data; CGM data only or with exogenous inputs [37] [36]. |

| 30 minutes | Median RMSE: 6.99 mg/dL [37] | Free-living data with exercise; personalized models [37]. | |

| 60 minutes | RMSE: ~1.73 mmol/L (~31.14 mg/dL) [36]; Recall (Hypo): 87% [1] | Free-living data; outperforms LR for hypoglycemia prediction at this horizon [1]. | |

| Logistic Regression [1] [38] | 15 minutes | Recall (Hypo): 98%; Recall (Normo): 91%; Recall (Hyper): 96% [1] | Free-living data; excels as a classifier for short-term glycemic state prediction [1]. |

| 60 minutes | Performance declines compared to shorter horizons [1] | Free-living data; outperformed by LSTM for longer horizons [1]. | |

| ARIMA [1] [35] | 15 minutes | Lower performance compared to LSTM and Logistic Regression [1] | Free-living data; struggles with non-linear glucose dynamics [1]. |

| 60 minutes | Underperforms LSTM and Logistic Regression [1] | Free-living data; limited capability with complex, multi-factorial data [1]. |

Table 2: Summary of Model Strengths and Data Requirements

| Model | Best Use Case | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | Medium- to long-term BG value prediction (30-90 mins); Classifying hypo-/hyperglycemia at longer horizons [37] [1]. | Captures complex temporal patterns and long-range dependencies; handles multivariate input well [39] [1]. | High computational cost; requires large amounts of data for training; "black box" nature [14]. |

| Logistic Regression | Short-term classification of glycemic states (e.g., 15 mins); Resource-constrained environments [1]. | Computationally efficient, simple to implement, and highly interpretable [1]. | Limited to classification; assumes linear relationships; performance drops with longer prediction horizons [1]. |

| ARIMA | Baseline model for linear time-series analysis; Scenarios with limited computational resources [14] [1]. | Computationally efficient and simple for univariate, linear time-series data [14]. | Poor performance with non-linear, complex datasets; cannot natively incorporate exogenous variables [1]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure the reproducibility of comparative studies, this section outlines standard protocols for data preprocessing and model training as employed in recent research.

Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

A consistent preprocessing pipeline is crucial for model performance. Common steps across studies include:

- Data Imputation and Alignment: Missing CGM data points for short gaps (e.g., <60 minutes) are typically estimated using linear interpolation. Longer gaps may lead to the exclusion of the corresponding data segment. Data from different sources (CGM, accelerometer, insulin pump) must be aligned to a common time frequency (e.g., 5-minute intervals) [39] [40] [36].

- Normalization: To improve model convergence and accuracy, each time series (e.g., glucose, insulin) is often normalized with respect to its own minimum and maximum values, transforming the data into a (0,1) range. An inverse transform is applied to the model's output to map predictions back to the original scale [39].

- Stationarity Check (for ARIMA): Before applying ARIMA, time series must be checked for stationarity using statistical tests like the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) and Kwiatkowski-Phillips-Schmidt-Shin (KPSS) tests. Non-stationary series are made stationary through differencing [40].

- Feature Engineering for Machine Learning: For LSTM and Logistic Regression, the time-series prediction problem is reframed as a supervised learning task. This involves using a sliding window of historical observations (e.g., 180 minutes of past data) as input features to predict future values [40] [13]. When only glucose data is available, features like the rate of change, rolling averages, and variability indices can be engineered to provide more context to the models [1].

Model Training and Evaluation

Robust training and evaluation methodologies are essential for unbiased performance estimates.

- Train-Test Splitting: Conventional random splitting is unsuitable for time-series data due to temporal dependencies. The Forward Chaining (FC) method, a rolling-based technique, is often employed. The model is trained on a chronological subset of data and tested on a subsequent, unseen period. This process is repeated to obtain a robust performance estimate [39].

- Personalized vs. Aggregated Training:

- Aggregated Training: A single model is trained on data combined from multiple individuals. This leverages larger datasets but may lack precision for individual variability [13].

- Personalized Training: A separate model is trained for each individual using only their own data. This can better capture individual patterns and has been shown to achieve accuracy comparable to aggregated models, even with less data [37] [13]. Another effective approach is to start with a population-based model and then fine-tune it on individual patient data [37].

- Evaluation Metrics: Models are evaluated using:

- Regression Metrics: Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for predicted glucose values [37] [39].

- Classification Metrics: Precision, Recall (Sensitivity), and Accuracy for predicting hypoglycemia, euglycemia, and hyperglycemia events [1].

- Clinical Safety: The Clarke Error Grid (CEG) or Continuous Glucose-Error Grid Analysis (CG-EGA) is used to assess the clinical accuracy of predictions, categorizing them into zones from A (clinically accurate) to E (erroneous and dangerous) [37] [39].

The following diagram illustrates a typical end-to-end workflow for developing and evaluating glucose prediction models.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details key datasets, software, and hardware resources essential for conducting research in glucose prediction for T1D.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Glucose Prediction Studies

| Resource | Type | Description & Function |

|---|---|---|

| OhioT1DM Dataset [40] [36] | Dataset | A widely used, publicly available clinical dataset containing CGM, insulin, carbohydrate, and physical activity data from 12 individuals with T1D over 8 weeks. Serves as a benchmark for model development and comparison. |

| T1DEXI (Type 1 Diabetes Exercise Initiative) [37] | Dataset | A dataset specifically focused on exercise in free-living conditions. Includes CGM, insulin pump, carbohydrate intake, and detailed exercise information for 79 patients, ideal for studying glycemic impact of physical activity. |

| HUPA UCM Dataset [13] | Dataset | Contains data from 25 T1D individuals in free-living conditions, including CGM, insulin, carbohydrate intake, and lifestyle metrics (steps, heart rate). Useful for developing personalized models. |

| UVA/Padova T1D Simulator [1] | Software/Model | An FDA-accepted simulator of T1D physiology. Used for in-silico testing and validation of glucose prediction and control algorithms before clinical trials. |

| CGM Simulator (e.g., Simglucose) [1] | Software/Model | A Python-based simulator that incorporates CGM sensor error profiles, useful for testing model robustness to noisy data. |

| Dexcom G6 CGM System [35] | Hardware | A real-time CGM system commonly used in research and clinical care. Provides glucose readings every 5 minutes, forming the primary data source for prediction models. |

| ActivPAL Accelerometer [36] | Hardware | A research-grade accelerometer used to objectively measure physical activity, which is a major confounding factor for glucose levels in free-living studies. |