From Glucose to ATP: Molecular Mechanisms, Metabolic Regulation, and Therapeutic Targeting

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the molecular machinery and regulatory networks governing cellular glucose uptake and utilization for ATP production.

From Glucose to ATP: Molecular Mechanisms, Metabolic Regulation, and Therapeutic Targeting

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the molecular machinery and regulatory networks governing cellular glucose uptake and utilization for ATP production. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational biochemistry with cutting-edge discoveries in signaling pathways and metabolic reprogramming. We explore advanced methodologies for investigating metabolic flux, examine dysregulation in disease contexts such as diabetes and cancer, and evaluate computational and experimental approaches for pathway optimization and therapeutic intervention. The scope spans from fundamental transport mechanisms to the application of machine learning and real-time metabolomics, offering an integrated perspective essential for innovating metabolic therapies.

The Core Machinery: Unraveling Glucose Transport and Metabolic Pathways

Glucose serves as the primary source of energy for metabolic processes in mammalian cells, fueling ATP production through glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation [1]. As a polar, hydrophilic molecule, glucose cannot freely diffuse across the lipophilic plasma membrane and requires specific carrier proteins for cellular uptake [2]. The study of glucose transporters is fundamental to understanding the mechanistic basis of glucose uptake and utilization for ATP production, with profound implications for metabolic diseases, cancer biology, and therapeutic development. Two principal families of transport proteins facilitate this process: the facilitative glucose transporters (GLUTs or SLC2A family) that enable passive glucose movement down concentration gradients, and the sodium-glucose cotransporters (SGLTs or SLC5A family) that mediate active transport against concentration gradients by coupling glucose uptake to sodium import [3] [1]. These transporters exhibit distinct tissue distributions, kinetic properties, and regulatory mechanisms that collectively maintain whole-body glucose homeostasis and ensure adequate substrate provision for cellular energy production.

The Facilitative Glucose Transporter (GLUT/SLC2A) Family

Structural Organization and Classification

The GLUT proteins are integral membrane proteins belonging to the major facilitator superfamily (MFS), characterized by 12 membrane-spanning α-helical domains with both amino and carboxyl termini exposed on the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane [4] [2]. These transporters operate via an alternate conformation model, exposing a single substrate binding site toward either the extracellular or intracellular environment [4]. Binding of glucose to one site triggers a conformational change that releases glucose to the opposite side of the membrane, with putative substrate binding regions located in transmembrane segments 9, 10, and 11 [4].

The human genome encodes 14 GLUT proteins categorized into three classes based on sequence similarity [4] [2]. Class I includes the most extensively characterized transporters GLUT1-4 and GLUT14, sharing 48-63% sequence identity and containing characteristic motifs including a QLS motif in transmembrane helix 7 associated with glucose selectivity [2]. Class II comprises GLUT5, GLUT7, GLUT9, and GLUT11, which lack the QLS motif and display divergent substrate specificities [2]. Class III includes GLUT6, GLUT8, GLUT10, GLUT12, and GLUT13 (HMIT), distinguished by conserved motifs in transmembrane domains and loops despite lower overall sequence identity (19-41%) [2].

Table 1: Classification and Properties of Major Facilitative Glucose Transporters (GLUTs)

| Transporter | Class | Gene | Tissue Distribution | Key Physiological Functions | Substrate Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLUT1 | I | SLC2A1 | Ubiquitous; high in erythrocytes, blood-brain barrier | Basal glucose uptake, blood-brain barrier transport [4] | Glucose, galactose, glucosamine [2] |

| GLUT2 | I | SLC2A2 | Liver, pancreatic β-cells, renal tubules, small intestine | Bidirectional transport, glucose sensing [5] [4] | Glucose, galactose, fructose [4] |

| GLUT3 | I | SLC2A3 | Neurons, placenta | High-affinity neuronal glucose transport [4] | Glucose [2] |

| GLUT4 | I | SLC2A4 | Skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, heart | Insulin-regulated glucose storage [6] [4] | Glucose [2] |

| GLUT5 | II | SLC2A5 | Small intestine, testes, kidney, adipose tissue | Fructose transport [5] [2] | Fructose [2] |

| GLUT8 | III | SLC2A8 | Testes, brain, liver, adipose tissue | Insulin-regulated in some tissues [5] | Glucose [2] |

| GLUT12 | III | SLC2A12 | Heart, prostate, placenta, mammary gland | Insulin-responsive transport [5] | Glucose [2] |

Tissue-Specific Functions and Regulatory Mechanisms

GLUT1 in Barrier Tissues and Erythrocytes

GLUT1 demonstrates widespread expression in fetal tissues and maintains high expression in adult erythrocytes and endothelial cells of barrier tissues such as the blood-brain barrier [4]. It provides the basal glucose uptake necessary to sustain cellular respiration across all cell types [1] [4]. GLUT1 expression is sensitive to glucose availability, with increased membrane localization under reduced glucose conditions [4]. Notably, GLUT1 overexpression represents a common feature in many tumors, supporting the heightened glycolytic flux characteristic of cancer cells [7] [4].

GLUT2 in Metabolic Sensing and Interorgan Coordination

GLUT2 functions as a high-capacity, low-affinity bidirectional transporter expressed in hepatocytes, pancreatic beta cells, renal tubular cells, and the basolateral membrane of intestinal epithelial cells [5] [4]. In hepatocytes, GLUT2 enables both glucose uptake for glycolysis and glycogen synthesis, as well as glucose release during gluconeogenesis [4]. pancreatic beta cells, GLUT2-mediated glucose transport facilitates glucose sensing and insulin secretion regulation, establishing a critical link between blood glucose levels and hormonal response [4].

GLUT3 in Neuronal Glucose Utilization

As the primary glucose transporter in neurons, GLUT3 exhibits high affinity for glucose, enabling efficient substrate capture even at low extracellular concentrations [4] [8]. This kinetic property is particularly crucial in brain tissue where glucose availability may fluctuate, ensuring a constant supply of glucose for neuronal energy metabolism and neurotransmitter synthesis [8].

GLUT4 in Insulin-Regulated Glucose Homeostasis

GLUT4 serves as the principal insulin-responsive glucose transporter, mediating the bulk of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake into skeletal muscle and adipose tissue [5] [6]. Under basal conditions, approximately 90% of GLUT4 resides within intracellular vesicles, rapidly translocating to the plasma membrane upon insulin stimulation or muscle contraction [6]. This translocation process increases the maximal velocity of glucose transport without altering substrate affinity [6]. Insulin signaling triggers GLUT4 externalization through two parallel pathways: one involving phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) activation and another requiring the proto-oncoprotein c-Cbl and its associated protein CAP, which activates the GTPase TC10 in lipid rafts [6]. Exercise-stimulated GLUT4 translocation occurs independently of PI3K via AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation, providing an alternative mechanism for enhancing glucose uptake during increased metabolic demand [6].

The critical importance of GLUT4 in metabolic health is underscored by its dysregulation in insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), where impaired GLUT4 translocation contributes to defective glucose disposal and hyperglycemia [6]. Research demonstrates that increasing intracellular GLUT4 concentrations can reverse insulin resistance in animal models, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target [6].

Diagram Title: GLUT4 Translocation Signaling Pathways

The Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter (SGLT/SLC5A) Family

Structural Basis of Secondary Active Transport

SGLTs constitute a distinct family of membrane transporters that utilize the electrochemical sodium gradient established by Na+/K+ ATPase to drive active glucose transport against concentration gradients [3]. These symporters belong to the sodium/solute symporter family (SSSF) within the SLC5A gene family and function through an alternating-access mechanism, cycling through multiple conformational states to transport substrates across the membrane [3]. Structural studies reveal that SGLT proteins contain 14 transmembrane helices (TM0-TM13) with a LeuT structural fold [9]. High-resolution cryo-EM structures have illuminated the molecular details of substrate recognition and transport, showing that SGLT2 transitions through outward-open, occluded, and inward-open conformations during its transport cycle [9].

The sodium-glucose cotransport process begins with the binding of sodium ions to the outward-facing transporter, increasing its affinity for glucose binding [8]. Subsequent conformational changes occlude the substrate binding site before transitioning to an inward-open conformation that releases first sodium then glucose into the cytoplasm [9] [8]. The transporter then returns to the outward-facing conformation to complete the cycle [9]. This mechanism allows SGLTs to accumulate glucose intracellularly even when extracellular concentrations are low, a critical function in the intestinal lumen and renal tubules [3].

Table 2: Characteristics of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporters (SGLTs)

| Transporter | Gene | Sodium:Glucose Stoichiometry | Tissue Distribution | Primary Physiological Functions | Substrate Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT1 | SLC5A1 | 2:1 | Small intestine (brush border), kidney (S3 segment) | Intestinal glucose absorption, renal glucose reabsorption [3] | Glucose, galactose [3] |

| SGLT2 | SLC5A2 | 1:1 | Kidney (S1/S2 segments of proximal tubule) | Bulk renal glucose reabsorption (80-90%) [3] [9] | Glucose [3] |

| SGLT3 | SLC5A4 | N/A (glucose sensor) | Small intestine, skeletal muscle, cholinergic neurons | Glucose sensing without transport [3] | Glucose [3] |

| SGLT4 | SLC5A9 | Sodium-dependent | Small intestine, kidney, liver, brain | Mannose, fructose, glucose transport [3] | Mannose, fructose, glucose [3] |

| SGLT5 | SLC5A10 | Sodium-dependent | Kidney | Glucose, galactose, fructose transport [3] | Glucose, galactose, fructose [3] |

| SGLT6 | SLC5A11 | Sodium-dependent | Brain, kidney | Glucose, myo-inositol transport [3] | Glucose, myo-inositol [3] |

Complementary Roles in Glucose Homeostasis

SGLT1 in Intestinal Glucose Absorption

SGLT1 serves as the primary mediator of dietary glucose absorption in the small intestine, located at the brush border membrane of enterocytes [10]. As a high-affinity, low-capacity transporter with 2:1 sodium:glucose stoichiometry, SGLT1 efficiently captures luminal glucose even at low concentrations [3] [10]. Recent research has revealed that in obesity, the adipose tissue-derived secretome enhances SGLT1 affinity for glucose through altered phosphorylation, potentially contributing to hyperglycemia and type 2 diabetes pathogenesis [10].

SGLT2 in Renal Glucose Reclamation

SGLT2 represents the dominant glucose transporter in the renal proximal tubule, responsible for reabsorbing 80-90% of filtered glucose [3] [9]. Its low-affinity, high-capacity transport characteristics complement SGLT1's high-affinity, low-capacity function in the later nephron segments [3]. The central role of SGLT2 in renal glucose handling has made it an attractive therapeutic target for diabetes management, with SGLT2 inhibitors promoting glycosuria and reducing hyperglycemia [3] [9].

Experimental Approaches in Glucose Transporter Research

Methodologies for Investigating Transporter Function

Glucose Uptake Assays in Cell Culture Systems

The assessment of glucose transporter activity typically employs radiolabeled or fluorescent glucose analogs in controlled cell culture systems. For SGLT function studies, the fluorescent substrate 1-NBD-glucose provides a sensitive measure of transport activity, with inhibition experiments using specific competitors like 4-deoxy-4-fluoro-D-glucopyranoside (4FDG) to characterize transporter kinetics [9]. These assays are conducted under sodium-containing buffers to maintain the sodium gradient essential for SGLT function, with potassium substitution serving as a negative control [9].

Detailed Protocol: SGLT Inhibition Assay

- Culture epithelial cells (e.g., IEC-18) to 80-90% confluence in appropriate medium

- Pre-incubate cells with experimental treatments (e.g., adipose-derived secretome) for specified durations [10]

- Replace medium with transport buffer containing 1-NBD-glucose (10-100 μM) with or without inhibitor (4FDG) [9]

- Incubate for precise time intervals (typically 2-10 minutes) at 37°C

- Terminate uptake by rapid washing with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline

- Lyse cells and quantify fluorescence using appropriate excitation/emission wavelengths (Ex: 465 nm, Em: 540 nm)

- Calculate kinetic parameters (Km, Vmax) from substrate saturation curves

Brush Border Membrane Vesicle (BBMV) Preparation

For transport studies in polarized epithelial cells, BBMV isolation provides a purified membrane system for characterizing transporter kinetics without confounding effects of intracellular metabolism.

Detailed Protocol: BBMV Preparation from Intestinal Tissue

- Isolate intestinal segments and flush with ice-cold saline

- Scrape mucosal layer and homogenize in hypotonic buffer (50 mM mannitol, 2 mM HEPES/Tris, pH 7.4)

- Add MgCl2 to 10 mM final concentration and incubate on ice for 20 minutes to aggregate intracellular membranes

- Centrifuge at 3,000 × g for 15 minutes to remove aggregated material

- Collect supernatant and centrifuge at 30,000 × g for 30 minutes to pellet BBMV

- Resuspend vesicles in appropriate buffer and assess purity by marker enzyme (alkaline phosphatase) enrichment [10]

Cryo-Electron Microscopy for Structural Analysis

High-resolution structural studies of glucose transporters utilize cryo-EM to capture conformational states during the transport cycle.

Detailed Protocol: SGLT2 Structural Analysis

- Express hSGLT2-MAP17 complex in mammalian cell system (e.g., HEK293 cells)

- Purify complex using affinity and size-exclusion chromatography

- Incubate with Fab90 antibody fragment to improve particle orientation [9]

- Prepare cryo-EM grids by applying sample and vitrifying in liquid ethane

- Collect images using modern cryo-EM equipped with direct electron detector

- Process images to generate 3D reconstructions at 2.5-3.5 Å resolution

- Build atomic models and analyze substrate binding sites and conformational states [9]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Glucose Transporter Research

| Reagent/Cell Line | Category | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-NBD-Glucose | Fluorescent substrate | SGLT transport assays | Non-metabolizable glucose analog for real-time uptake measurement [9] |

| 4FDG | Transport competitor | SGLT inhibition studies | Glucose analog that competes with substrate binding [9] |

| Cytochalasin B | GLUT inhibitor | GLUT binding studies | High-affinity inhibitor that binds to intracellular site [2] |

| IEC-18 cells | Cell line | Intestinal transport studies | Rat intestinal epithelial cell line for SGLT1 regulation [10] |

| Fab90 antibody | Structural biology tool | Cryo-EM studies | Monoclonal antibody fragment improving SGLT2 particle orientation [9] |

| HEK293 cells | Expression system | Transporter overexpression | Mammalian cell line for recombinant GLUT/SGLT expression [9] |

| Obese Zucker Rat | Animal model | Obesity/metabolism studies | Genetic obesity model for adipose-tissue regulation of transporters [10] |

Diagram Title: Glucose Transporter Research Workflow

Pathophysiological Implications and Therapeutic Targeting

Dysregulation of glucose transporters features prominently in metabolic disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, and cancer [5] [7] [2]. In type 2 diabetes, impaired GLUT4 translocation in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue contributes to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia [6]. Simultaneously, increased SGLT1-mediated intestinal glucose absorption may exacerbate postprandial hyperglycemia [10]. Therapeutically, SGLT2 inhibitors have emerged as effective antidiabetic agents that promote urinary glucose excretion, while selective SGLT1 inhibition represents an emerging approach targeting intestinal glucose absorption [3]. In cancer biology, upregulated GLUT1 expression supports the Warburg effect and increased glycolytic flux in tumor cells, positioning GLUT inhibitors as potential anticancer agents [7]. Neurologically, disrupted glucose transporter expression at the blood-brain barrier (GLUT1) and in neurons (GLUT3) may contribute to neurodegenerative processes in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases through impaired energy metabolism [2]. These pathophysiological connections highlight the fundamental importance of glucose transport systems in health and disease, reinforcing their value as therapeutic targets across multiple disease states.

The entry of glucose into the cell is a critical first step in energy production, serving as a fundamental process in cellular metabolism. Glucose uptake is mediated by specialized membrane transport proteins that overcome the impermeability of the phospholipid bilayer to hydrophilic molecules [11]. Two primary mechanisms facilitate this process: facilitated diffusion and secondary active transport. These systems enable the controlled passage of glucose from the extracellular environment into the cytoplasm, where it can undergo glycolysis and subsequent oxidative phosphorylation to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP) [12]. The specific mechanism employed varies by cell type, physiological context, and energy requirements, creating a complex regulatory landscape essential for maintaining metabolic homeostasis. Understanding these distinct transport pathways is crucial for research focused on neuronal bioenergetics, metabolic disorders, and drug development targeting nutrient uptake pathways.

Facilitated Diffusion: Passive Transit via Carrier Proteins

Mechanism and Molecular Players

Facilitated diffusion is a passive transport process where carrier proteins mediate the selective passage of molecules down their concentration gradient without direct energy expenditure [11]. The transported molecules do not dissolve in the phospholipid bilayer; instead, their passage is enabled by proteins that allow them to cross the membrane without interacting with its hydrophobic interior [11]. For glucose, this process is accomplished by the GLUT (GLucose Transporters) family of proteins, which are integral membrane proteins containing 12 membrane-spanning helices with both amino and carboxyl termini exposed on the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane [4].

These transporters operate according to an alternating conformation model, where the transporter exposes a single substrate-binding site toward either the outside or the inside of the cell [4]. The binding of glucose to one site provokes a conformational change associated with transport, releasing glucose to the other side of the membrane [4]. The inner and outer glucose-binding sites are thought to be located in transmembrane segments 9, 10, and 11 [4].

Table 1: Key Facilitative Glucose Transporters (GLUTs) in Mammalian Cells

| Transporter | Primary Tissue Distribution | Kinetic Properties (Km) | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| GLUT1 | Erythrocytes, blood-brain barrier, fetal tissues | ~1 mM [12] | Basal glucose uptake; responsible for low-level glucose required to sustain respiration in all cells [4] |

| GLUT2 | Liver, pancreatic beta cells, renal tubular cells | 15-20 mM [12] | Bidirectional transport; high-capacity, low-affinity transporter; functions in glucose sensing [4] |

| GLUT3 | Neurons, placenta | ~1 mM [12] | High-affinity neuronal glucose transporter; ensures glucose supply even during low glucose availability [4] |

| GLUT4 | Adipose tissue, skeletal and cardiac muscle | ~5 mM [12] | Insulin-responsive transporter; responsible for regulated glucose storage [4] |

Kinetic Properties and Regulation

The transport kinetics of facilitated diffusion follows a saturable pattern characteristic of carrier-mediated processes. The glucose transporter alternates between two conformational states [11]. In the first conformation, a glucose-binding site faces the outside of the cell, where glucose binding induces a conformational change in the transporter so the glucose-binding site faces the interior, allowing release into the cytosol [11]. The affinity of different GLUT isoforms for glucose varies significantly, with Km values (the concentration at which transport is half-maximal) ranging from approximately 1 mM for high-affinity transporters like GLUT1 and GLUT3 to 15-20 mM for low-affinity transporters like GLUT2 [12].

Regulation of these transporters occurs through multiple mechanisms. While most GLUT transporters are constitutively active at the plasma membrane, GLUT4 represents a specialized case of regulated trafficking. Under basal conditions, GLUT4 resides primarily in cytoplasmic vesicles. Upon insulin binding to its receptor, a signaling cascade triggers the translocation of GLUT4-containing vesicles to the cell surface, dramatically increasing glucose uptake into muscle and adipose tissue [12]. This process represents a critical point of dysregulation in metabolic diseases like diabetes.

Secondary Active Transport: Coupled Energy Utilization

Sodium-Glucose Cotransport Mechanism

In contrast to facilitated diffusion, secondary active transport couples the movement of glucose against its concentration gradient to the facilitated diffusion of a second solute (usually an ion) down its electrochemical potential [13]. This mechanism is particularly important in epithelial absorption contexts, such as the intestinal lumen and renal tubules, where glucose must be extracted from low-concentration environments into the bloodstream [12].

The sodium-glucose cotransporters (SGLTs) exemplify this mechanism through a symport process, where both sodium and glucose are transported in the same direction across the membrane [12]. The established sodium gradient provides the driving force for this process. The Na+/K+ ATPase pump actively extrudes three sodium ions from the cell while importing two potassium ions, consuming ATP in the process and creating both a low intracellular sodium concentration and an electrochemical gradient favoring sodium entry [12] [14]. This gradient represents stored energy that SGLT proteins harness to co-transport glucose against its concentration gradient.

Table 2: Sodium-Glucose Cotransporters (SGLTs) in Mammalian Systems

| Transporter | Tissue Distribution | Sodium:Glucose Stoichiometry | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT1 | Small intestine (brush border), kidney (distal tubule) | 2:1 [12] | High-affinity, low-capacity glucose absorption; responsible for dietary glucose uptake |

| SGLT2 | Kidney (proximal tubule) | 1:1 [12] | Low-affinity, high-capacity glucose reabsorption; responsible for ~90% of renal glucose reabsorption |

Renal Glucose Reabsorption: A Case Study

The kidney provides a compelling physiological example of secondary active transport coordination. In the nephron, SGLT2 transporters located in the early proximal tubule reabsorb the majority of filtered glucose from the tubular lumen [12]. These transporters have a low affinity but high capacity for glucose, handling the bulk of glucose reabsorption when glucose concentrations are high. Further along the tubule, SGLT1 transporters with high affinity but low capacity recapture remaining glucose, ensuring minimal glucose loss in urine under normal physiological conditions [12]. The glucose transported into the epithelial cells then exits into the bloodstream via facilitated diffusion through GLUT2 transporters located on the basolateral membrane [12].

Experimental Methodologies for Studying Glucose Transport

Transport Kinetics and Inhibition Assays

Characterizing glucose transporter function requires specialized methodologies to quantify uptake rates and kinetic parameters. The patch clamp technique, developed by Erwin Neher and Bert Sakmann in 1976, enables the study of ion channel activity by using a micropipette with a tip diameter of about 1 μm to isolate a small patch of membrane, allowing the flow of ions through a single channel to be analyzed [11]. While particularly useful for studying ion channels, this technique can be adapted to study electrogenic transporters like SGLT that generate current during transport cycles.

For kinetic analysis, researchers often employ radiolabeled glucose analogs (e.g., 2-deoxy-D-[³H]glucose) to measure uptake rates over time under varying substrate concentrations. By measuring initial uptake rates at different glucose concentrations, researchers can determine Km and Vmax values using Michaelis-Menten kinetics. Specific inhibitors can further distinguish between transport mechanisms: phlorizin competitively inhibits SGLT transporters, while cytochalasin B blocks facilitative GLUT transporters.

Metabolic Flux Analysis

Understanding how transport mechanisms influence cellular energy production requires assessment of metabolic flux. Cellular respirometry assays, particularly using platforms like the Seahorse XF Analyzer, enable real-time measurement of oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) as proxies for mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis, respectively [15]. This approach allows researchers to correlate transport activity with downstream metabolic pathways.

In practice, cells are subjected to sequential injections of metabolic inhibitors: oligomycin (ATP synthase inhibitor), FCCP (mitochondrial uncoupler), and rotenone/antimycin A (electron transport chain inhibitors) [16]. The resulting OCR profile reveals key parameters of mitochondrial function, including basal respiration, ATP-linked respiration, proton leak, and spare respiratory capacity. Simultaneous ECAR measurements provide insight into glycolytic flux, creating a comprehensive picture of cellular bioenergetics.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Glucose Transport and Metabolism Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Transport Inhibitors | Phlorizin, Cytochalasin B | Distinguish between SGLT and GLUT-mediated transport mechanisms [12] |

| Metabolic Inhibitors | Oligomycin, FCCP, Rotenone, Antimycin A, 2-Deoxyglucose | Probe mitochondrial function and glycolytic capacity in respirometry assays [15] [16] |

| Labeled Tracers | 2-Deoxy-D-[³H]glucose, [¹⁴C]glucose | Quantify glucose uptake rates and metabolic fate |

| Imaging Tools | Mitochondrial dyes (e.g., TMRM, MitoTracker), GLUT-GFP constructs | Visualize subcellular localization of organelles and transporters |

Physiological Context and Research Implications

Neuronal Energetics and Glucose Transport

The brain's heavy reliance on glucose as a primary fuel source makes neuronal glucose transport a critical research area. Interestingly, neurons express primarily GLUT3, a high-affinity transporter (Km ~1 mM) that ensures sufficient glucose supply even during periods of low glucose availability [12] [4]. This is particularly important given that brain glucose concentrations typically range between 1-3 mM, significantly lower than standard cell culture media containing 25 mM glucose [15].

Recent research has revealed that this discrepancy in glucose concentration significantly impacts neuronal metabolism. Neurons cultured in standard hyperglycemic media (25 mM glucose) show heavy dependence on glycolysis for ATP production, contrary to the predominant reliance on oxidative phosphorylation observed in vivo [15]. In contrast, neurons cultured in more physiological glucose conditions (5 mM) demonstrate a more balanced dependence on glycolysis and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, greater reserve mitochondrial respiration capacity, and increased mitochondrial population [15]. These findings highlight how transport mechanisms interface with downstream metabolic pathways and suggest that historical in vitro studies may have misrepresented neuronal energy metabolism.

Disease Connections and Therapeutic Targeting

Dysregulation of glucose transport mechanisms contributes to various pathological conditions. In diabetes, impaired GLUT4 translocation in response to insulin represents a fundamental defect in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue glucose uptake [12] [4]. Meanwhile, in cancer, many tumors exhibit upregulated GLUT1 expression, enabling enhanced glucose uptake to support aerobic glycolysis (the Warburg effect) and biomass production for rapid proliferation [4].

Therapeutic interventions have been developed to target specific transport mechanisms. SGLT2 inhibitors (e.g., canagliflozin, dapagliflozin) represent a recent class of diabetes drugs that block renal glucose reabsorption, promoting glucosuria and reducing blood glucose levels [12]. Research is also exploring modulators of GLUT expression and trafficking as potential therapeutic approaches for metabolic disorders and cancer.

Comparative Analysis and Research Integration

Side-by-Side Mechanistic Comparison

The fundamental differences between facilitated diffusion and secondary active transport for glucose entry can be summarized across multiple parameters:

- Energy Requirement: Facilitated diffusion operates passively without direct energy input, while secondary active transport indirectly consumes ATP via the maintenance of ion gradients [11] [12]

- Directionality: Facilitated diffusion is bidirectional, with net flow determined by concentration gradients; secondary active transport is typically unidirectional under physiological conditions [11] [13]

- Consequence of Transport: Facilitated diffusion equilibrates glucose concentrations across membranes; secondary active transport creates and maintains concentration gradients [11] [12]

- Tissue Distribution: Facilitated diffusion via GLUT transporters occurs in nearly all cell types; secondary active transport via SGLT is specialized for epithelial absorption [12] [4]

- Kinetic Properties: GLUT transporters exhibit Km values ranging from 1-20 mM depending on isoform; SGLT transporters generally have lower Km values, suited for extracting glucose from low-concentration environments [12]

Integrated View of Glucose Utilization for ATP Production

The interplay between glucose transport mechanisms and ATP production forms a coordinated system for cellular energy management. Glucose entry represents the first committed step in a metabolic cascade that culminates in ATP generation through glycolysis in the cytoplasm and oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria. The specific transport mechanism employed influences the rate and regulation of this process.

In cells utilizing facilitated diffusion, glucose uptake is primarily governed by extracellular glucose concentrations and the kinetic properties of the expressed GLUT isoforms. For instance, neurons with high GLUT3 expression can maintain consistent glucose uptake even during brief fluctuations in glucose availability, supporting their continuous high energy demands [4]. Conversely, in cells employing secondary active transport, glucose uptake is coupled to ion gradients that are actively maintained, allowing accumulation against concentration gradients but at the cost of indirect energy expenditure.

Diagram 1: Glucose Transport Mechanisms Comparison

The cellular entry of glucose via facilitated diffusion and secondary active transport represents a finely tuned system that matches uptake mechanisms to tissue-specific requirements. Facilitated diffusion through GLUT proteins provides efficient, regulated transport down concentration gradients, while secondary active transport via SGLT cotransporters enables active accumulation against concentration gradients at the expense of pre-established ion gradients. Understanding these mechanisms and their interface with downstream metabolic pathways for ATP production is essential for research on neuronal bioenergetics, metabolic diseases, and therapeutic development. The experimental methodologies outlined provide researchers with tools to dissect these processes in health and disease, offering insights for future investigations into cellular energy metabolism.

Diagram 2: Experimental Analysis of Glucose Metabolism

Glycolysis, also known as the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas (EMP) pathway, is a universal metabolic pathway that serves as the foundational mechanism for glucose catabolism in virtually all organisms, from microbes to mammals [17] [18]. This evolutionarily ancient biochemical sequence occurs in the cytosol of cells and functions as the initial stage of cellular energy production, converting a single six-carbon glucose molecule into two three-carbon pyruvate molecules while generating a net yield of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) [18] [19]. For research scientists and drug development professionals, understanding the intricate regulation of this pathway is paramount, particularly given its central role in pathological conditions such as cancer (the Warburg effect) and metabolic disorders like type 2 diabetes [20] [21] [22].

The glycolytic sequence represents a critical interface between glucose uptake mechanisms and ATP production systems within the cell. Recent research has revealed that glycolytic enzymes can form self-organizing wave structures on the cell membrane and cortex, suggesting a previously unrecognized level of spatial organization that may locally enhance ATP production to fuel energy-intensive processes such as cell migration and macropinocytosis [22]. This compartmentalization challenges the traditional view of glycolysis as a purely cytosolic process and opens new avenues for therapeutic intervention in diseases characterized by aberrant metabolic states. Furthermore, exercise-stimulated glucose uptake demonstrates how glycolytic flux can be dramatically increased through mechanisms distinct from insulin signaling, preserving metabolic flexibility even in insulin-resistant states [21]. This review provides a comprehensive technical analysis of the glycolytic sequence, with particular emphasis on its regulatory mechanisms, experimental methodologies for flux quantification, and implications for drug discovery targeting metabolic diseases.

The Glycolytic Pathway: A Two-Phase Process

Glycolysis proceeds through ten enzyme-catalyzed reactions that can be conceptually divided into two distinct phases: the energy investment phase and the energy payoff phase [17] [18]. This division reflects the metabolic strategy of initial ATP expenditure to activate glucose, followed by energy recovery and net gain through substrate-level phosphorylation.

Phase 1: Energy Investment

The first phase of glycolysis prepares the glucose molecule for cleavage by phosphorylating and rearranging it into two interconvertible three-carbon sugars. This preparatory phase consumes two ATP molecules per glucose molecule [18] [23].

Step 1: Phosphorylation to Glucose-6-Phosphate - The enzyme hexokinase (in most tissues) or glucokinase (in liver and pancreatic β-cells) catalyzes the transfer of a phosphate group from ATP to glucose, forming glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) [18]. This reaction is physiologically irreversible and serves to trap glucose within the cell by adding a charged phosphate group that cannot easily cross the plasma membrane [20] [18].

Step 2: Isomerization to Fructose-6-Phosphate - Phosphoglucose isomerase converts the aldose sugar (G6P) to the ketose sugar fructose-6-phosphate (F6P) through an isomerization reaction [18]. This step prepares the molecule for the subsequent phosphorylation at carbon 1.

Step 3: Second Phosphorylation to Fructose-1,6-Bisphosphate - Phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK-1), a key regulatory enzyme, catalyzes the transfer of a second phosphate group from ATP to F6P, yielding fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (F1,6BP) [18]. This committed step of glycolysis is highly exergonic and represents the primary rate-limiting control point of the pathway.

Step 4: Aldol Cleavage - The enzyme fructose bisphosphate aldolase cleaves the six-carbon F1,6BP into two different three-carbon sugars: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P) and dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) [18].

Step 5: Triose Phosphate Interconversion - Triosephosphate isomerase rapidly catalyzes the reversible isomerization of DHAP to G3P, ensuring both three-carbon products can proceed through the remainder of the pathway [18]. At this point, the first phase concludes with one glucose molecule yielding two molecules of G3P.

Phase 2: Energy Payoff

The second phase of glycolysis extracts energy through oxidation and substrate-level phosphorylation, generating ATP and NADH from the G3P molecules produced in the first phase [18] [19].

Step 6: Oxidation to 1,3-Bisphosphoglycerate - Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase catalyzes the first redox reaction of glycolysis, oxidizing G3P while simultaneously incorporating inorganic phosphate (Pi) to produce 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate (1,3-BPG) [18]. During this reaction, NAD+ is reduced to NADH, capturing high-energy electrons from the oxidized aldehyde group.

Step 7: First ATP Generation - Phosphoglycerate kinase facilitates the transfer of a high-energy phosphate group from 1,3-BPG to ADP, forming 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PG) and ATP [18]. This constitutes the first substrate-level phosphorylation event in glycolysis.

Step 8: Phosphate Group Migration - Phosphoglycerate mutase relocates the phosphate group from carbon 3 to carbon 2 of the glycerate backbone, converting 3-PG to 2-phosphoglycerate (2-PG) [18].

Step 9: Dehydration to Phosphoenolpyruvate - The enzyme enolase catalyzes the dehydration of 2-PG to form phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), creating a high-energy enol phosphate bond [18].

Step 10: Second ATP Generation - Pyruvate kinase, another key regulatory enzyme, catalyzes the irreversible transfer of the phosphate group from PEP to ADP, generating pyruvate and ATP [18]. This final step completes the glycolytic sequence.

Table 1: Quantitative Input and Output of the Glycolytic Sequence

| Parameter | Input/Output | Quantity per Glucose Molecule |

|---|---|---|

| Input | Glucose | 1 |

| ATP | 2 | |

| NAD+ | 2 | |

| Inorganic Phosphate (Pi) | 2 | |

| ADP | 4 | |

| Output | Pyruvate | 2 |

| Net ATP | 2 | |

| NADH | 2 | |

| H₂O | 2 |

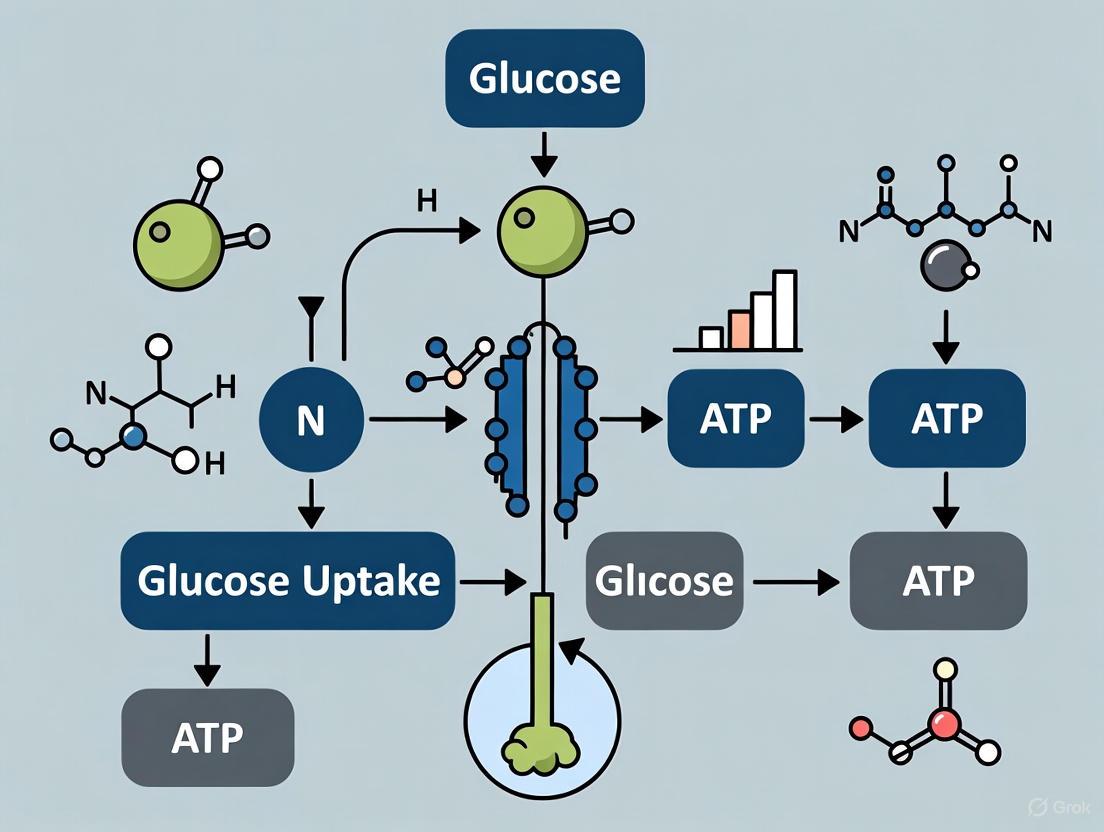

The following diagram illustrates the complete glycolytic pathway with its two distinct phases, key enzymes, and intermediate metabolites:

Diagram 1: The complete glycolytic pathway from glucose to pyruvate, showing energy investment and payoff phases, key enzymes, and cofactor utilization.

Metabolic Fate of Pyruvate and Regulation

Post-Glycolytic Pathways

Pyruvate, the end product of glycolysis, occupies a critical metabolic branch point whose fate depends on cellular conditions and organism type [17] [19]. Under aerobic conditions in most tissues, pyruvate is transported into the mitochondria where it undergoes oxidative decarboxylation to acetyl-CoA via the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex [20]. This acetyl-CoA then enters the citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle), generating additional NADH and FADH₂ molecules that drive oxidative phosphorylation to produce the majority of ATP (up to approximately 30 additional ATP molecules per glucose) [24] [19]. Conversely, under anaerobic conditions or in tissues with limited mitochondrial capacity, pyruvate is reduced to lactate through lactic acid fermentation, regenerating NAD+ from NADH to allow glycolysis to continue in the absence of oxygen [18] [19]. This anaerobic pathway yields only the net 2 ATP molecules from glycolysis itself but is crucial for maintaining energy production during oxygen debt or in cells like erythrocytes that lack mitochondria entirely [18].

Allosteric and Hormonal Regulation

Glycolytic flux is tightly regulated through multiple mechanisms to match cellular energy demands with nutrient availability [18]. The three key irreversible steps catalyzed by hexokinase/glucokinase, phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK-1), and pyruvate kinase serve as primary regulatory nodes through allosteric effectors and hormonal signaling [18].

Phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK-1) represents the most important control point, inhibited by high levels of ATP and citrate (indicating ample energy and biosynthetic precursors), and activated by AMP and fructose-2,6-bisphosphate (signaling energy depletion) [18]. Fructose-2,6-bisphosphate, produced by phosphofructokinase-2 (PFK-2), serves as a potent allosteric activator whose concentration is regulated by insulin and glucagon, thus linking glycolytic flux to hormonal status [18].

Pyruvate kinase, the final key regulatory enzyme, is allosterically inhibited by ATP and activated by fructose-1,6-bisphosphate, implementing a feed-forward activation mechanism that ensures coordinated flux through the latter stages of glycolysis [18]. The liver isoform is also regulated through phosphorylation by glucagon-activated protein kinase A, which decreases enzyme activity during fasting states [18].

Hexokinase is inhibited by its product glucose-6-phosphate, providing feedback regulation when glycolytic intermediates accumulate [18]. The liver-specific glucokinase isoform has a higher Km for glucose and is not subject to product inhibition, allowing the liver to respond to postprandial glucose elevations [18].

The following diagram illustrates the complex regulatory network controlling glycolytic flux:

Diagram 2: Regulatory network of glycolysis showing allosteric inhibition/activation and hormonal control mechanisms.

Table 2: Key Regulatory Enzymes in Glycolysis and Their Modulators

| Enzyme | Activators | Inhibitors | Physiological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hexokinase | - | Glucose-6-phosphate | Prevents accumulation of glycolytic intermediates when downstream metabolism is limited [18] |

| Glucokinase | Insulin (induction) | - | Liver enzyme with high Km allows response to postprandial glucose elevation [18] |

| Phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK-1) | AMP, Fructose-2,6-bisphosphate, ADP | ATP, Citrate, H+ | Primary rate-controlling step; inhibited when energy and biosynthetic precursors are abundant [18] |

| Pyruvate Kinase | Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate | ATP, Alanine, Glucagon (via PKA phosphorylation) | Coordinates final step with upstream flux; reduced activity during fasting [18] |

Research Methodologies and Experimental Approaches

Stable Isotope Tracing for Metabolic Flux Analysis

Advanced techniques for quantifying glycolytic flux have become essential tools in metabolic research, particularly for investigating pathological states such as cancer metabolism [25]. Stable isotope tracing represents a powerful methodology that enables researchers to track the fate of individual atoms through the glycolytic pathway and connected metabolic networks. In this approach, cells or organisms are fed substrates labeled with stable isotopes (e.g., ¹³C-glucose), and the incorporation of these labels into downstream metabolites is quantified using mass spectrometry or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [25]. This technique allows researchers to determine relative flux through various metabolic pathways, identify alternative routing of carbons, and detect compartmentalized metabolite pools. For Crabtree-positive yeasts and cancer cells, protocols have been developed that combine ¹³C-glucose labeling with computational modeling to quantitatively assess glycolytic flux and its contribution to central carbon metabolism [25]. The resulting flux maps provide unprecedented insight into how metabolic networks are rewired in disease states and in response to therapeutic interventions.

Assessing Glycolytic Function in Physiological Contexts

In mammalian systems, particularly in research on exercise metabolism and insulin resistance, several standardized protocols have been developed to assess glycolytic capacity and regulation [21]. The oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) measures the body's ability to clear glucose from the bloodstream following an oral glucose load, providing insight into whole-body glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity [20]. For more reductionist approaches in cell culture systems, glycolytic rate can be determined by measuring extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) using specialized analytical instrumentation, as lactic acid production from glycolysis lowers the pH of the media [21]. Additional biochemical assays include measuring lactate accumulation, glucose consumption, and enzyme activities in cell or tissue extracts. For exercise studies, measurements of arterial-venous glucose differences across working muscles, combined with stable isotope tracers, have revealed that skeletal muscle glucose uptake can increase by up to 50-fold during physical activity through mechanisms that remain functional even in insulin-resistant states [21].

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for experimental assessment of glycolytic function:

Diagram 3: Generalized experimental workflow for assessing glycolytic function using metabolic measurements and stable isotope tracing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Glycolysis Research

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Specific Examples/Context |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Tracers | Tracking metabolic flux through glycolysis and interconnected pathways | ¹³C-glucose for mass spectrometry-based flux analysis [25] |

| GLUT Transporters | Studying glucose uptake mechanisms; tissue-specific expression patterns | GLUT4 (adipocytes, muscle), GLUT1 (RBCs, blood-brain barrier) [18] |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | Probing specific steps in glycolytic pathway; potential therapeutic agents | 2-deoxyglucose (hexokinase inhibitor), Oxamate (LDH inhibitor) |

| Glycolytic Enzymes (Tagged) | Visualizing subcellular localization and dynamics | GFP-tagged aldolase, PFK for live-cell imaging of wave dynamics [22] |

| Metabolic Phenotyping Assays | Measuring glycolytic output and capacity | Extracellular acidification rate (ECAR), lactate production assays [21] |

| Allosteric Modulators | Studying regulatory mechanisms of key control points | Fructose-2,6-bisphosphate (PFK-1 activator) [18] |

Implications for Disease and Therapeutic Development

The glycolytic sequence represents more than just a core metabolic pathway—it is a dynamic, highly regulated system whose dysfunction underpins numerous pathological conditions. In cancer biology, the Warburg effect (aerobic glycolysis) describes the propensity of cancer cells to favor glycolysis over oxidative phosphorylation even in oxygen-rich environments [22]. Recent research has revealed that this metabolic reprogramming may be facilitated by the self-organizing wave behavior of glycolytic enzymes at the cell cortex, which creates localized compartments of enhanced glycolytic activity that fuel invasive behaviors [22]. Specifically, studies across human mammary epithelial and other cancer cell lines with increasing metastatic potential demonstrate that wave activity and glycolytic ATP levels increase in parallel, suggesting a mechanistic link between spatial organization of glycolysis and cancer progression [22].

In metabolic diseases, particularly type 2 diabetes, impaired glucose metabolism results from defects in both insulin signaling and cellular glucose utilization [20] [21]. Notably, exercise-stimulated glucose uptake occurs through mechanisms distinct from insulin signaling and remains functional in insulin-resistant muscle, highlighting glycolysis as a therapeutic target for bypassing insulin resistance [21]. Research has shown that exercise recruits multiple redundant signaling pathways—sensing either alterations in the intracellular metabolic milieu (mediated by AMPK) or mechanical stress (partly mediated by RAC1)—to increase glucose transport and glycolytic flux [21]. This redundancy ensures maintenance of muscle energy supply during physical activity and provides multiple potential intervention points for restoring metabolic health.

The comprehensive understanding of glycolytic regulation and the development of sophisticated research methodologies for assessing metabolic flux have positioned this ancient pathway as a promising target for therapeutic intervention across a spectrum of diseases. From small molecule inhibitors targeting specific glycolytic enzymes in cancer to exercise mimetics that activate glucose uptake in metabolic disease, the continued elucidation of glycolytic mechanisms promises to yield novel approaches for manipulating cellular metabolism in human disease.

The complete oxidation of glucose is the cornerstone of aerobic energy metabolism, with the majority of its potential energy harvested not in glycolysis but within the mitochondrion. While glycolysis breaks down glucose into pyruvate in the cytosol for a net gain of two ATP molecules, the subsequent orchestrated processes of the Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) cycle and oxidative phosphorylation are required to unleash the full energy yield, producing more than 30 additional ATP molecules per glucose [26] [20]. This mitochondrial phase of glucose catabolism is not merely an energy-generating pathway; it is a critical hub of cellular signaling and metabolism, and its dysregulation is implicated in a spectrum of diseases, from diabetes to neurodegenerative disorders. Understanding the precise mechanisms of the TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation is therefore paramount for research aimed at modulating cellular energy status for therapeutic benefit.

The Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle: A Central Metabolic Hub

The TCA cycle, also known as the Krebs or citric acid cycle, serves as the final common pathway for the oxidation of fuel molecules—carbohydrates, fatty acids, and amino acids. In eukaryotic cells, it is localized to the mitochondrial matrix.

Sequential Enzymatic Steps and Key Outputs

The cycle begins when acetyl-CoA, derived from pyruvate (the end-product of glycolysis) or fatty acid beta-oxidation, condenses with oxaloacetate. This reaction, catalyzed by citrate synthase, forms citrate and initiates a sequence of eight enzymatic steps that regenerate oxaloacetate [27] [28]. The cycle results in the complete oxidation of the acetyl group to two molecules of CO₂ and the generation of high-energy electron carriers.

Table 1: Enzymatic Steps and Outputs of the TCA Cycle

| Step | Reaction | Enzyme | Key Products (per acetyl-CoA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acetyl-CoA + Oxaloacetate → Citrate | Citrate synthase | - |

| 2 | Citrate Isocitrate | Aconitase | - |

| 3 | Isocitrate → α-Ketoglutarate | Isocitrate dehydrogenase | 1 NADH, 1 CO₂ |

| 4 | α-Ketoglutarate → Succinyl-CoA | α-Ketoglutarate dehydrogenase | 1 NADH, 1 CO₂ |

| 5 | Succinyl-CoA → Succinate | Succinyl-CoA synthetase | 1 GTP (or ATP) |

| 6 | Succinate → Fumarate | Succinate dehydrogenase | 1 FADH₂ |

| 7 | Fumarate → Malate | Fumarase | - |

| 8 | Malate → Oxaloacetate | Malate dehydrogenase | 1 NADH |

For each molecule of glucose, which yields two acetyl-CoA molecules, the net output of the TCA cycle is doubled: six NADH, two FADH₂, two GTP (or ATP), and four CO₂ [27] [28]. The GTP produced by succinyl-CoA synthetase can be readily converted to ATP by nucleoside-diphosphate kinase [28].

Anaplerotic and Cataplerotic Functions

Beyond energy production, the TCA cycle provides critical precursors for biosynthetic pathways, a function termed "cataplerosis." Key intermediates are siphoned off for processes like gluconeogenesis (oxaloacetate), fatty acid synthesis (citrate), and heme synthesis (succinate) [27]. To maintain cycle function, these depleted intermediates must be replenished via "anaplerotic" reactions, such as the carboxylation of pyruvate to form oxaloacetate [29].

Regulatory Mechanisms

The TCA cycle is exquisitely regulated by substrate availability, product inhibition, and allosteric effectors to match cellular energy demands. Key control points include:

- Citrate synthase, inhibited by ATP and citrate.

- Isocitrate dehydrogenase, the rate-limiting enzyme, which is allosterically stimulated by ADP and inhibited by NADH and ATP.

- α-Ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, inhibited by its products, NADH and succinyl-CoA, and by high ATP levels [27] [28].

This regulatory network ensures the cycle slows when cellular energy charge is high (high ATP/ADP and NADH/NAD⁺ ratios) and accelerates when energy demand increases.

Oxidative Phosphorylation: Chemiosmotic Coupling and ATP Synthesis

The primary role of the TCA cycle is to generate reducing equivalents in the form of NADH and FADH₂. These electron carriers donate electrons to the electron transport chain (ETC), fueling the process of oxidative phosphorylation, which generates the vast majority of cellular ATP [26].

The Electron Transport Chain

The ETC consists of four protein complexes (I-IV) embedded in the inner mitochondrial membrane, along with two mobile electron carriers, coenzyme Q (ubiquinone) and cytochrome c [26] [30].

- Complex I (NADH-CoQ oxidoreductase): Accepts electrons from NADH and transfers them to coenzyme Q, coupling this transfer to the pumping of four protons from the matrix to the intermembrane space [30].

- Complex II (Succinate-CoQ oxidoreductase): Catalyzes the oxidation of succinate to fumarate in the TCA cycle, transferring electrons via FADH₂ to coenzyme Q. This step is not coupled to proton pumping [26].

- Complex III (CoQ-cytochrome c oxidoreductase): Transfers electrons from reduced coenzyme Q to cytochrome c, pumping four protons in the process [26].

- Complex IV (Cytochrome c oxidase): Transfers electrons from cytochrome c to molecular oxygen (O₂), the final electron acceptor, forming water. This complex pumps two protons across the membrane [26].

Table 2: Proton and ATP Yield from Electron Carriers

| Electron Carrier | Entry Point | Protons Pumped | ~ATP Yield (Theoretical Max) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NADH | Complex I | 10 H⁺ (4 from I, 4 from III, 2 from IV) | 2.5 ATP |

| FADH₂ | Complex II | 6 H⁺ (0 from II, 4 from III, 2 from IV) | 1.5 ATP |

Chemiosmotic Coupling and ATP Synthase

The energy released from electron flow through the ETC is used to pump protons (H⁺) from the mitochondrial matrix to the intermembrane space. This establishes an electrochemical gradient, or proton-motive force, with both a chemical (pH) gradient and an electrical (membrane potential) component [26] [30].

ATP synthase (Complex V) harnesses this stored energy. As protons flow back into the matrix through a channel in the F₀ subunit of ATP synthase, the energy drives the rotation of part of the complex. This mechanical energy is coupled to the synthesis of ATP from ADP and inorganic phosphate (Pᵢ) in the catalytic F₁ subunit [26]. The flow of approximately four protons is required for the synthesis of one ATP molecule [26].

Integrating the outputs of glycolysis, the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, the TCA cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation provides the total ATP yield from one molecule of glucose.

Table 3: Theoretical Maximum ATP Yield from Complete Glucose Oxidation

| Metabolic Process | ATP Yield (Net) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis | 2 ATP | Substrate-level phosphorylation |

| Pyruvate Dehydrogenase | 0 ATP | Produces 2 NADH (cytosolic) |

| TCA Cycle (2 turns) | 2 GTP | Substrate-level phosphorylation; GTP = ATP |

| 6 NADH | From 2 acetyl-CoA | |

| 2 FADH₂ | From 2 acetyl-CoA | |

| Oxidative Phosphorylation | ||

| 2 NADH (Glycolysis) | 5 ATP | ~2.5 ATP/NADH via malate-aspartate shuttle |

| 2 NADH (PDH) | 5 ATP | ~2.5 ATP/NADH |

| 6 NADH (TCA) | 15 ATP | ~2.5 ATP/NADH |

| 2 FADH₂ (TCA) | 3 ATP | ~1.5 ATP/FADH₂ |

| Total | 32 ATP | Theoretical maximum |

This theoretical yield of 32 ATP per glucose is a maximum; in practice, the yield is lower due to proton leakage and the cost of transporting metabolites across membranes [26] [30].

Research Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Studying mitochondrial function requires a multidisciplinary approach to dissect the integrated processes of the TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation.

Isolating Functional Mitochondria

Protocol: Mitochondrial Isolation from Rodent Skeletal Muscle

- Tissue Homogenization: Euthanize the animal and rapidly excise skeletal muscle (e.g., gastrocnemius). Mince the tissue in ice-cold isolation buffer (containing 100 mM sucrose, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) to preserve organelle integrity.

- Differential Centrifugation:

- Centrifuge the homogenate at 800 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to pellet nuclei and cellular debris.

- Transfer the supernatant to a new tube and centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The resulting pellet contains the intact mitochondrial fraction.

- Washing: Gently resuspend the mitochondrial pellet in fresh isolation buffer and repeat the high-speed centrifugation step to wash the mitochondria.

- Protein Quantification: Resuspend the final mitochondrial pellet in a small volume of buffer and determine protein concentration using a Bradford or BCA assay for normalization in subsequent functional assays.

Measuring Oxygen Consumption

The rate of oxygen consumption is a direct indicator of ETC activity and overall mitochondrial function. This is typically measured using a Clark-type oxygen electrode in a sealed, stirred chamber maintained at 37°C.

- Basal Respiration: Add isolated mitochondria to the chamber containing respiration buffer. Record the oxygen consumption rate (State 2 respiration).

- ADP-Stimulated Respiration: Add a known amount of ADP. In the presence of excess substrates (e.g., pyruvate and malate), mitochondria rapidly consume oxygen to phosphorylate ADP to ATP (State 3 respiration). This measures the maximum phosphorylating capacity.

- Uncoupled Respiration: After ADP is depleted, the respiration rate slows (State 4). Addition of an uncoupler like FCCP dissipates the proton gradient, forcing the ETC to operate at maximum velocity independent of ATP synthase, revealing the electron transport system's intrinsic capacity.

Assessing Membrane Potential and ROS Production

- Membrane Potential (ΔΨm): Fluorescent dyes like Tetramethylrhodamine, Methyl Ester (TMRM) are accumulated by energized mitochondria in a membrane potential-dependent manner. A decrease in fluorescence indicates depolarization of ΔΨm, a key parameter of mitochondrial health [31].

- Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Production: The ETC is a major source of ROS. Dihydroethidium (DHE) or MitoSOX Red (targeted to mitochondria) can be used to detect superoxide production. Fluorescence intensity is proportional to ROS levels.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Assays

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Mitochondrial Function Analysis

| Reagent / Assay | Function / Target | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Rotenone | Inhibits Complex I | Used to probe the contribution of NADH-linked substrates to respiration. |

| Antimycin A | Inhibits Complex III | Halts electron flow, allowing measurement of upstream ETC function and non-mitochondrial oxygen consumption. |

| Oligomycin | Inhibits ATP Synthase | Induces State 4 respiration; used to measure proton leakage and calculate coupling efficiency. |

| FCCP | Uncoupler | Dissipates the proton gradient, unmasking maximum ETC capacity. |

| TMRM / JC-1 | ΔΨm-sensitive dyes | Quantitative and qualitative assessment of mitochondrial membrane potential by fluorescence. |

| Seahorse XF Analyzer | Live-cell metabolic profiling | Platform for simultaneously measuring oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) in live cells. |

| Antibodies (Total/OxPhos) | OXPHOS complexes | Western blotting to determine the protein expression levels of individual ETC complexes. |

Integrated View: From Glucose Uptake to ATP Production

Glucose metabolism is a continuous pathway from the cell surface to the mitochondrial matrix. Insulin or exercise-stimulated signaling pathways, such as those involving AMPK and CaMK, promote the translocation of the GLUT4 glucose transporter to the plasma membrane, allowing glucose entry [21] [32]. After glycolysis, the resulting pyruvate is actively transported into the mitochondrion. There, it is decarboxylated to acetyl-CoA, which enters the TCA cycle. The cycle's reduction of NAD⁺ to NADH and FAD to FADH₂ provides the high-energy electrons that drive the ETC. The chemiosmotic coupling of electron transport to ATP synthesis ultimately transforms the chemical energy of glucose into the universal energy currency, ATP. This integrated system allows the cell to adapt to energetic demands, and its dysregulation is a hallmark of metabolic disease, making its components prime targets for therapeutic intervention.

The precise regulation of glucose uptake and utilization is fundamental to cellular energy homeostasis and is governed by a complex interplay of hormonal signals and allosteric mechanisms. This whitepaper delineates the sophisticated regulatory networks involving insulin, glucagon, and key metabolites such as citrate and fatty acids in controlling glucose metabolism for ATP production. We synthesize recent advances demonstrating how hormonal signaling pathways—insulin via its receptor and AKT cascade, glucagon through cAMP-mediated processes—orchestrate glucose transporter trafficking and enzymatic activity. Furthermore, we explore emerging paradigms of allosteric control, including metabolite transporter interactions (NaCT/GLUT) and fatty-acid-mediated modulation of insulin receptor phosphorylation via CD36-Fyn kinetics. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this review integrates structural, functional, and pharmacological insights with experimental protocols and reagent solutions to support ongoing mechanistic investigations and therapeutic innovation in metabolic diseases.

Glucose serves as the primary metabolic fuel for mammals, and its regulated uptake and conversion to ATP are critical for cellular function [20]. The hormonal systems of insulin and glucagon provide a classic endocrine framework for maintaining blood glucose homeostasis, while allosteric regulation by metabolites allows for rapid, localized fine-tuning of metabolic fluxes [33] [34]. Insulin, secreted by pancreatic β-cells in response to elevated blood glucose, promotes glucose uptake into muscle and adipose tissue via the GLUT4 transporter and stimulates glycogenesis, thereby lowering blood glucose [34]. Conversely, glucagon, released from pancreatic α-cells during hypoglycemia, elevates blood glucose by triggering hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis [35].

Beyond this canonical hormonal balance, recent research reveals intricate crosstalk at the molecular level. Allosteric regulation, where molecules bind to regulatory sites on proteins to modulate their activity, is a key mechanism. Metabolites including citrate and fatty acids can directly influence transporter function and insulin signaling efficacy [36] [37]. For instance, the liver citrate transporter NaCT interacts with glucose transporters to synchronize nutrient uptake, while the fatty acid transporter CD36 forms complexes with the insulin receptor to enhance its tyrosine phosphorylation [36] [37]. Disruptions in these pathways are hallmarks of metabolic diseases such as Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM), characterized by insulin resistance and dysregulated glucagon secretion [20] [35]. This whitepaper delves into the molecular mechanics of these regulatory systems, providing a technical foundation for research aimed at diagnosing and treating metabolic disorders.

Hormonal Regulation of Glucose Metabolism

Insulin Signaling and Glucose Utilization

The insulin signaling cascade begins with insulin binding to its transmembrane receptor (IR), a receptor tyrosine kinase, leading to its autophosphorylation and activation [38]. The activated IR then phosphorylates direct substrates, primarily Insulin Receptor Substrate (IRS) proteins, which recruit and activate phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) [38]. PI3K catalyzes the production of phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3) from phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), a critical step that recruits downstream effectors like phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) and Protein Kinase B (AKT) to the plasma membrane [38]. AKT activation is a central node in metabolic signaling, promoting the translocation of the glucose transporter GLUT4 from intracellular vesicles to the cell surface via phosphorylation and inactivation of proteins such as RAB GAP AS160 (TBC1D4) [38]. This results in a tenfold increase in glucose uptake into muscle and adipose cells [38]. AKT also stimulates glycogen synthesis and inhibits gluconeogenesis, thereby coordinating a reduction in blood glucose levels [38]. Defects in this pathway, such as impaired IR tyrosine phosphorylation or reduced AKT activity, are pivotal in the development of insulin resistance [37] [38].

Table 1: Key Effectors in the Insulin Signaling Pathway

| Protein/Component | Function in Signaling | Downstream Metabolic Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Insulin Receptor (IR) | Receptor tyrosine kinase; autophosphorylates upon insulin binding | Initiates the metabolic signaling cascade |

| IRS1/2 | Docking proteins for IR; phosphorylated by IR | Recruits and activates PI3K |

| PI3K | Kinase that converts PIP2 to PIP3 | Generates lipid second messenger for AKT recruitment |

| AKT (PKB) | Serine/threonine kinase; key signaling node | Promotes GLUT4 translocation, glycogen synthesis, inhibits gluconeogenesis |

| AS160 (TBC1D4) | RAB GAP; inactivated by AKT phosphorylation | Releases inhibition on GLUT4 vesicle trafficking |

| GLUT4 | Insulin-responsive glucose transporter | Facilitates glucose uptake into muscle and adipose tissue |

Glucagon Signaling and Hepatic Glucose Output

Glucagon acts primarily on the liver to elevate blood glucose levels during fasting or stress. It binds to glucagon receptors, which are G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) primarily linked to Gs proteins [35]. This binding activates adenylate cyclase (AC), increasing intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels. cAMP then activates Protein Kinase A (PKA), which in turn phosphorylates and activates key enzymes like phosphorylase kinase. This cascade culminates in the stimulation of glycogenolysis (breakdown of glycogen to glucose) and gluconeogenesis (synthesis of glucose from non-carbohydrate precursors like amino acids) [35] [34]. Glucagon also regulates amino acid metabolism and lipid oxidation, highlighting its role as a broader regulator of energy balance [35]. In diabetes, dysregulated glucagon secretion—hyperglucagonemia—and hepatic "glucagon resistance" contribute significantly to fasting and postprandial hyperglycemia, making the glucagon pathway a target for therapeutic intervention [35].

Diagram 1: Glucagon signaling pathway in hepatocytes, showing key steps from receptor binding to glucose output.

Allosteric Regulation by Metabolites

Metabolite Transporter Interactions: NaCT and GLUT

Emerging evidence positions metabolite transporters not merely as passive conduits but as active regulators of cellular metabolism through allosteric interactions. A seminal discovery is the functional coordination between the sodium-coupled citrate transporter (NaCT, SLC13A5) and glucose transporters (GLUTs) in hepatocytes [36]. This interaction forms a "first-line" metabolic pathway that synchronizes the uptake of citrate and glucose in response to nutrient availability. During glucose starvation, citrate uptake increases, potentially to substitute for glucose in energy production. Upon glucose re-saturation, this increased uptake is halted. Inhibition of NaCT disrupts this synchronization and paradoxically elevates glucose uptake, suggesting that NaCT exerts an allosteric-like, reciprocal regulation on GLUT function [36]. This transceptor interaction is mediated by a specific region, the H4c helix on transmembrane domain 4 of NaCT, and controls cellular bioenergetics by coordinating the influx of two key carbon sources [36].

CD36-Fyn Kinase Modulation of the Insulin Receptor

The fatty acid transporter CD36 provides another layer of allosteric regulation by directly influencing the insulin receptor (IR). CD36 forms a complex with IR and the Src-family kinase Fyn, which promotes Fyn-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of IR, thereby enhancing its activity and the subsequent recruitment of downstream effectors like PI3K [37]. This mechanism is crucial for optimal insulin responsiveness in skeletal muscle. Notably, this enhancement is sensitive to the type of dietary fatty acids: saturated fatty acids rapidly disrupt the CD36-Fyn interaction, suppressing IR phosphorylation, while unsaturated fatty acids are neutral or stimulatory [37]. This represents a nutrient-sensing, allosteric mechanism where metabolites (fatty acids) directly modulate a key hormonal signaling pathway. Genetically determined low levels of CD36 in muscle are linked to impaired glucose disposal and a higher incidence of type 2 diabetes, underscoring its pathophysiological relevance [37].

Table 2: Allosteric Regulators of Glucose Metabolic Pathways

| Allosteric Regulator | Molecular Target | Effect on Target/Pathway | Physiological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated Fatty Acids | CD36-Fyn-IR complex | Dissociates complex, suppresses IR phosphorylation [37] | Contributes to insulin resistance |

| Citrate | Phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK-1) | Allosteric inhibitor [36] | Slows glycolysis when TCA cycle is full |

| Extracellular Citrate (via NaCT) | GLUT transporters | Reciprocally regulates transport function [36] | Synchronizes glucose/citrate uptake for energy management |

| Glucose (D-Glucose) | GLUT1 transporter | Accelerates exchange flux (allosteric accelerator) [39] | Increases transport efficiency |

Experimental Methodologies for Investigating Regulation

Investigating Insulin Receptor Phosphorylation and Interaction

Protocol: Co-immunoprecipitation and Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA) for CD36-IR Complex This protocol is used to demonstrate the physical and functional interaction between CD36 and the Insulin Receptor [37].

- Cell Culture and Treatment: Use primary-derived human skeletal muscle myotubes (HSMMs) or CHO cells stably expressing human IR and CD36. Serum-starve cells for 16 hours before treatment. Pre-treat cells with saturated (e.g., palmitate) or unsaturated (e.g., oleate) fatty acids complexed with BSA (2:1 ratio) for 15 minutes, followed by insulin stimulation (e.g., 100 nM) for a defined period (e.g., 10-30 minutes) [37].

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells in ice-cold lysis buffer (e.g., 20 mM Tris-HCL pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 60 mM octyl β-d-glucopyranoside, plus protease and phosphatase inhibitors) for 30-60 minutes. Clear lysates by centrifugation at 10,000g for 10 minutes [37].

- Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP): Determine protein concentration of the supernatant. Incubate lysates with an antibody against CD36 or IR overnight at 4°C. Add Protein A/G beads for 2-4 hours to capture the immune complexes. Wash beads extensively with lysis buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins [37].

- Immunoblotting: Elute proteins from beads, separate by SDS-PAGE, and transfer to a membrane. Probe the membrane with antibodies against phospho-tyrosine, IRβ, and CD36 to assess interaction and phosphorylation status [37].

- Proximity Ligation Assay (In Situ): For visual confirmation of protein complexes in cells or tissue sections. Culture cells on coverslips, treat, and then fix with ice-cold methanol. Block and incubate with primary antibodies against CD36 and IRβ overnight. Follow the Duolink PLA kit instructions: add PLUS and MINUS PLA probes, ligate, and amplify with a fluorescent DNA circle. Mount and image using a fluorescence microscope. Red fluorescent spots indicate close proximity (<40 nm) of CD36 and IR [37].

Synchronized Metabolite Transport Assay

Protocol: Measuring Synchronized Citrate and Glucose Uptake in Hepatocytes This protocol assesses the coordinated transport of citrate and glucose via NaCT and GLUT [36].

- Primary Hepatocyte Isolation and Culture: Isolate primary mouse hepatocytes or use human hepatocyte lines (e.g., THLE2, HepG2). Culture cells in appropriate media [36].

- Glucose Starvation and Re-saturation: Subject cells to glucose-free medium for varying periods (4, 6, 8, 10 hours) to simulate starvation. For re-saturation, add glucose back to the medium for set times (30, 120, 240 minutes) after an 8-hour fast [36].

- Radiolabeled Uptake Measurement:

- Citrate Uptake: Incubate cells with ³H-citrate for a set time (e.g., 15 minutes). Terminate the reaction by washing with ice-cold PBS. Solubilize cells and measure radioactivity by liquid scintillation counting [36].

- Glucose Uptake: Similarly, measure the uptake of ³H-2-deoxyglucose (³H-2-DG), a non-metabolizable glucose analog. Incubate cells with ³H-2-DG, wash extensively with cold PBS containing excess unlabeled 2-DG, and count radioactivity [36].

- Pharmacological Inhibition: To probe NaCT's role, repeat uptake measurements in the presence of a specific NaCT inhibitor (e.g., BI01383298) across a range of concentrations. This will demonstrate the dependency of synchronized transport on NaCT function [36].

- Data Analysis: Normalize uptake counts to total cellular protein. Plot uptake rates against starvation/re-saturation time or inhibitor concentration to visualize synchronization and its disruption.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for studying hormonal and allosteric regulation of glucose metabolism.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Research on Metabolic Regulation

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Specificity | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| CD36 siRNA | Silences CD36 gene expression | Investigating CD36's role in insulin receptor signaling and glucose uptake [37] |

| NaCT Inhibitor (BI01383298) | Potent and specific inhibitor of the SLC13A5 citrate transporter | Probing the role of citrate transport in synchronized glucose/citrate uptake and cellular bioenergetics [36] |

| ³H-2-Deoxyglucose (2-DG) | Non-metabolizable glucose analog for tracing uptake | Measuring rates of glucose transporter activity [37] [36] |

| ³H-Citrate | Radiolabeled citrate for transport studies | Quantifying citrate uptake via NaCT and other transporters [36] |

| Phospho-specific Antibodies | Detect phosphorylated proteins (e.g., p-Tyrosine, p-AKT) | Assessing activation status of insulin signaling pathways [37] |

| Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA) Kit | Visualizes protein-protein interactions in situ | Validating close proximity between CD36 and IR, or other interacting proteins [37] |

| Palmitate-BSA / Oleate-BSA complexes | Deliver saturated or unsaturated fatty acids to cells | Studying the allosteric effects of different fatty acids on insulin signaling [37] |

| Seahorse XF Analyzer | Measures cellular metabolic fluxes in real-time (glycolysis, mitochondrial respiration) | Functional assessment of metabolic pathway utilization after hormonal or genetic perturbation [37] |

Advanced Tools for Profiling Metabolic Flux and Energetics

Hyperpolarized 13C-NMR and Real-Time Tracking of Glycolytic Kinetics

The study of glycolysis, the fundamental pathway converting glucose to pyruvate for ATP production, has been revolutionized by the advent of hyperpolarized 13C-Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. This transformative technology enables real-time, non-invasive observation of metabolic kinetics with unprecedented temporal resolution, revealing dynamic cellular processes previously inaccessible to researchers. Traditional metabolic assays provide static snapshots of metabolite concentrations, but fail to capture the rapid flux through glycolytic pathways that is crucial for understanding energy metabolism in diverse contexts from cancer to immune cell activation [40] [41].

At its core, this technique addresses a critical gap in metabolic research: the ability to directly observe substrate influx and conversion through central carbon metabolism on a timescale of seconds. By temporarily enhancing NMR sensitivity by more than four orders of magnitude, hyperpolarized 13C-NMR allows researchers to track the fate of 13C-labeled substrates as they traverse the glycolytic pathway in living systems, providing unique insights into the kinetic barriers and regulatory checkpoints that govern glucose utilization for ATP production [40]. This technical guide explores the methodology, applications, and implementation of hyperpolarized 13C-NMR for investigating the mechanistic details of glucose uptake and utilization.

Technical Foundations of Hyperpolarized 13C-NMR

Fundamental Principles and Mechanism