Ex Vivo Jejunal Sac Assay: A Comprehensive Guide to Measuring Glucose Absorption for Drug Discovery and Research

This article provides a detailed guide on the ex vivo everted jejunal sac technique, a fundamental tool for investigating intestinal glucose absorption mechanisms.

Ex Vivo Jejunal Sac Assay: A Comprehensive Guide to Measuring Glucose Absorption for Drug Discovery and Research

Abstract

This article provides a detailed guide on the ex vivo everted jejunal sac technique, a fundamental tool for investigating intestinal glucose absorption mechanisms. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, the content spans from foundational principles of sodium-glucose cotransport (SGLT1) to advanced methodological protocols, troubleshooting, and validation against other techniques like the Ussing chamber. It also explores applications in evaluating functional ingredients and pharmacological inhibitors, synthesizing key insights to inform future research in metabolic diseases and nutrient absorption.

Unraveling the Mechanisms: The Science of Jejunal Glucose Transport

Core Principles of Transcellular and Paracellular Glucose Absorption

The small intestine serves as the primary site for dietary glucose uptake, a process critical for maintaining systemic energy homeostasis. Intestinal glucose absorption occurs via two principal pathways: transcellular (through the enterocytes) and paracellular (between the enterocytes) transport. Understanding the mechanisms governing these pathways is essential for research in metabolic diseases, drug development, and nutrient absorption. This application note details the core principles of these absorption routes and provides a standardized experimental protocol for their investigation using ex vivo everted jejunal sacs, a cornerstone technique for direct measurement of nutrient uptake. The protocol is framed within a broader thesis on ex vivo measurement, enabling precise quantification of absorption kinetics and the contribution of specific transporters.

Core Absorption Pathways

Glucose absorption in the small intestine is a complex process involving coordinated activity of specific transporters and regulated epithelial permeability.

Transcellular Transport

The transcellular pathway involves the movement of glucose across the enterocyte, a process mediated by specific transporter proteins located on the apical and basolateral membranes.

- Apical Membrane Uptake: At physiologically low luminal glucose concentrations (typically less than 30 mM), the primary route for apical entry is active transport via the Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 1 (SGLT1) [1] [2]. SGLT1 couples the transport of one glucose molecule with two sodium ions, utilizing the sodium gradient established by Na+/K+ ATPase on the basolateral membrane as its driving force [1]. This process is saturable and can be competitively inhibited by phloridzin [1] [2].

- Basolateral Membrane Efflux: Once inside the enterocyte, glucose exits into the lamina propria and bloodstream via facilitated diffusion through the GLUT2 transporter located on the basolateral membrane [1]. GLUT2 has a higher capacity but lower affinity for glucose compared to SGLT1.

Table 1: Key Transcellular Glucose Transporters

| Transporter | Location | Mechanism | Kinetic Property | Inhibitor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT1 | Apical Membrane | Active, Na+-dependent | High affinity, Low capacity | Phloridzin |

| GLUT2 | Basolateral Membrane | Facilitated Diffusion | Low affinity, High capacity | Phloretin |

At high luminal glucose concentrations (>30 mM), a secondary, rapid-response mechanism may be recruited. Evidence suggests that GLUT2 can be translocated to the apical membrane, providing a high-capacity pathway for glucose uptake via facilitated diffusion, though the physiological significance of this pathway is still debated [1] [2].

Paracellular Transport

The paracellular pathway allows for the passive movement of glucose and other solutes through the tight junctions between adjacent enterocytes.

- This pathway becomes particularly relevant at high intraluminal glucose concentrations when active transport via SGLT1 is saturated [1].

- The absorption is primarily driven by a solvent drag effect, where the osmotic gradient created by active solute absorption pulls water, along with dissolved glucose, through the tight junctions [1] [3].

- The permeability of the tight junctions is dynamically regulated by proteins such as claudin, which controls the size and charge selectivity of the paracellular space [2]. Increased paracellular permeability, including for ions like Na+, has been observed in fasted states, potentially optimizing absorption upon refeeding [2].

Table 2: Characteristics of Intestinal Glucose Absorption Pathways

| Feature | Transcellular Pathway | Paracellular Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Route | Through the enterocyte | Between enterocytes |

| Primary Mechanism | Carrier-mediated (SGLT1/GLUT2) | Passive solvent drag |

| Energy Dependence | Active (SGLT1) | Passive |

| Saturability | Yes | No |

| Involvement of Tight Junctions | No | Yes (Claudins) |

| Dominant Luminal [Glucose] | Low (< 30 mM) | High (> 30 mM) |

Experimental Protocol: Everted Jejunal Sac Assay

The following protocol is optimized for the investigation of transcellular and paracellular glucose absorption mechanisms, incorporating key experimental considerations from recent literature.

Reagents and Materials

- Animals: Male Wistar rats (~250 g) or C57BL/6 mice. Note: Fasting status (e.g., 24-hour fast) significantly upregulates jejunal SGLT1 activity and must be standardized [2].

- Buffers:

- Krebs-Ringer Bicarbonate (KRB) Buffer: 118 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 2.5 mM CaCl₂, 1.2 mM MgSO₄, 1.2 mM KH₂PO₄, 25 mM NaHCO₃, 0.5 mM L-glutamine, 10 µM indomethacin. Gas with 95% O₂/5% CO₂ to pH 7.4 [2].

- Glucose Solution: 100 mM D-glucose in isotonic saline. For sensitive quantification, include a radioactive tracer (e.g., ¹⁴C-D-glucose) or a non-metabolizable analog like ¹⁴C-Methyl-α-D-glucopyranoside (MGP) [4] [2].

- Mannitol Solution: 100 mM D-mannitol with a tracer (e.g., ¹⁴C-Mannitol) as a paracellular permeability marker [4].

- Pharmacological Agents:

- Equipment: Dissection toolkit, water bath (37°C), carbogen (95% O₂/5% CO₂) supply, oxygenation tubes, scintillation counter (if using radiolabels).

Step-by-Step Procedure

Tissue Preparation:

- Euthanize the animal humanely and perform a midline laparotomy. Excise the entire small intestine rapidly.

- Flush the intestine with ice-cold, pre-oxygenated KRB buffer to remove luminal contents.

- Gently evert the jejunal segment (identified as the segment 10-20 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz) over a glass rod or using fine forceps, creating a serosal-out mucosal-in sac.

- Cut the everted segment into 3-4 cm lengths.

Sac Incubation:

- Fill each sac with 0.5-1 mL of pre-warmed, oxygenated KRB buffer (serosal solution).

- Ligate both ends of the sac securely and place it in a glass tube containing 10-20 mL of pre-warmed, oxygenated KRB buffer (mucosal solution).

- For experimental groups, supplement the mucosal solution with:

- Group 1 (Total Absorption): 100 mM Glucose + ¹⁴C-Glucose/MGP.

- Group 2 (Transcellular Inhibition): 100 mM Glucose + ¹⁴C-Glucose/MGP + 1 mM Phloridzin.

- Group 3 (Paracellular Marker): 100 mM Mannitol + ¹⁴C-Mannitol.

- Gas the incubation tubes continuously with 95% O₂/5% CO₂ and maintain in a shaking water bath at 37°C for a predetermined time (e.g., 30-60 minutes).

Sample Collection and Analysis:

- After incubation, remove the sacs from the tubes, gently blot dry, and weigh.

- Puncture the sac and collect the serosal fluid.

- Measure the glucose concentration in the serosal fluid and mucosal solution using a glucose assay kit or HPLC.

- If using radiolabels, measure the radioactivity in serosal fluid and mucosal solution using a liquid scintillation counter to calculate the appearance rate of the tracer [4].

Data Calculation:

- Calculate the Glucose Transport Rate (nmol/min/cm² or nmol/min/g tissue).

- Calculate the Mannitol Apparent Permeability (Papp) as a marker of paracellular integrity and flux.

- The phloridzin-sensitive component represents SGLT1-mediated active transport. The remaining glucose flux in the presence of phloridzin, correlated with mannitol Papp, indicates the paracellular contribution.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Glucose Absorption Studies

| Research Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| ¹⁴C-D-Glucose / ¹⁴C-MGP | Radioactive tracer for sensitive quantification of total glucose absorption flux; MGP is non-metabolizable [4] [2]. |

| ¹⁴C-Mannitol | Paracellular permeability marker; measures the integrity and flow through the tight junction pathway [4]. |

| Phloridzin | Selective, competitive inhibitor of SGLT1; used to isolate and block the active transcellular transport component [1] [2]. |

| Triaminopyrimidine | Inhibitor of paracellular tight junction permeability; used to block the solvent-drag-mediated absorption pathway [3]. |

| Everted Jejunal Sac | Classic ex vivo model that maintains tissue cytoarchitecture, allowing for separate sampling of mucosal and serosal compartments to measure net transport [5]. |

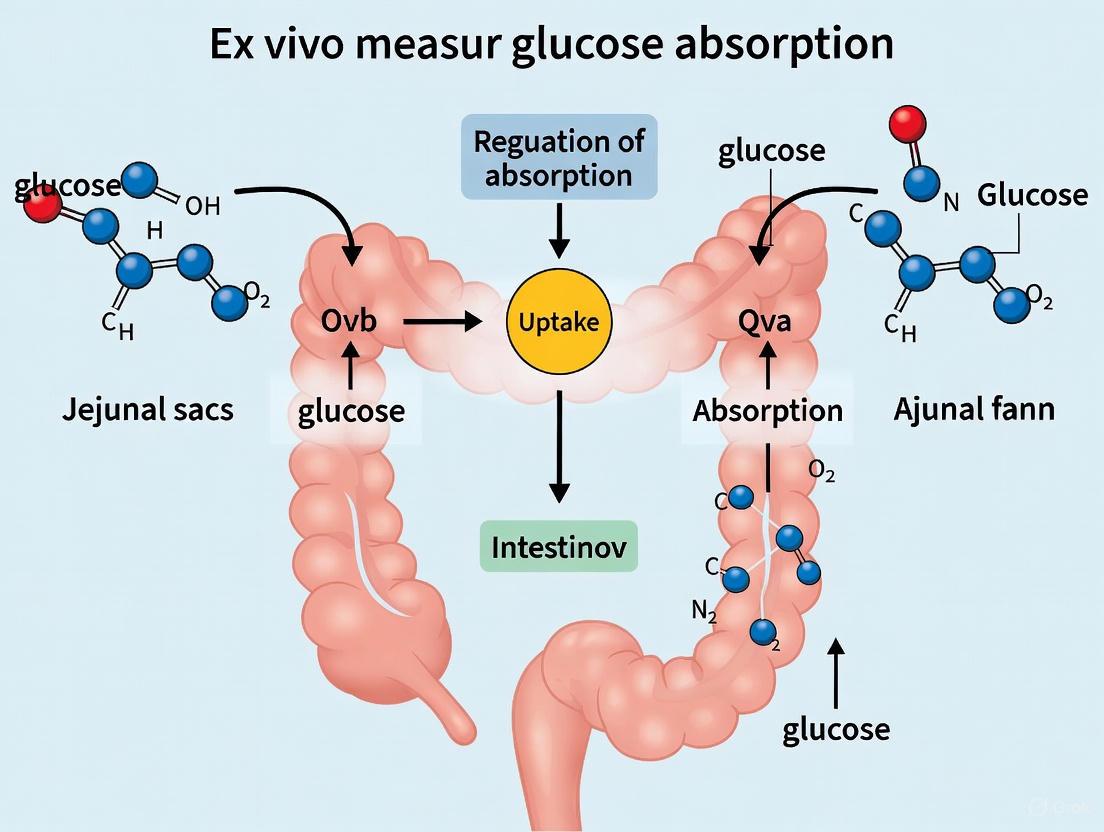

Visualization of Pathways and Workflow

The following diagrams illustrate the molecular mechanisms of glucose absorption and the experimental workflow for the everted sac protocol.

Glucose Absorption Mechanisms

Everted Sac Experimental Workflow

Within the context of research utilizing ex vivo jejunal sacs, a precise understanding of the key transporters mediating glucose absorption is fundamental. This absorption is a coordinated, multi-step process primarily orchestrated by three transporter systems: the sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1) on the apical membrane, the facilitative glucose transporter 2 (GLUT2) on the basolateral membrane, and the sodium-potassium pump (Na+/K+-ATPase) that energizes the entire system [6] [7]. The functional interplay between these transporters ensures efficient uptake of dietary glucose from the intestinal lumen into the bloodstream. This application note details their distinct roles, quantitative kinetic parameters, and provides validated experimental protocols for investigating their function in ex vivo models, specifically tailored for the jejunal sac preparation.

Transporter Profiles and Quantitative Kinetic Data

The following table summarizes the core functional characteristics and localization of the three key transporters in the enterocyte.

Table 1: Key Transporters in Intestinal Glucose Absorption

| Transporter | Primary Localization | Transport Mechanism | Key Function | Reported Km for Glucose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT1 | Apical (Brush Border) Membrane [6] | Secondary active Na+-glucose symport (2 Na+:1 glucose) [7] | Mediates uphill uptake of glucose from the lumen into the enterocyte [6] | 2-6 mM (in vitro); 6-23 mM (in vivo, with unstirred layer effects) [8] |

| GLUT2 | Basolateral Membrane [6] [9] | Facilitated diffusion | Mediates glucose efflux from enterocyte into blood [9] [7] | ~17 mM (Low affinity, high capacity) [9] |

| Na+/K+-ATPase | Basolateral Membrane [10] [11] | Primary active transport (3 Na+ out: 2 K+ in) | Maintains transcellular Na+ gradient, the driving force for SGLT1 [10] | N/A (Pumps ions, not glucose) |

The diagram below illustrates the coordinated workflow of glucose absorption and its investigation in an ex vivo jejunal sac model, integrating the physiological process with key experimental assessment points.

Diagram 1: Integrated glucose absorption pathway and ex vivo investigation points. EECs: Enteroendocrine Cells; MGP: Methyl α-D-glucopyranoside.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Jejunal Sac Studies

Protocol 1: Measuring SGLT1-Mediated Glucose Uptake Using Radiolabeled Tracers

This protocol is adapted from methods used in knockout mouse studies to directly quantify apical glucose influx [6].

- Objective: To quantify the specific contribution of SGLT1 to total glucose uptake in ex vivo jejunal sacs.

- Principle: The non-metabolizable glucose analog α-Methyl-D-glucopyranoside (AMG) or D-glucose combined with a radiolabeled tracer (e.g., [¹⁴C(U)]-D-glucose) is used. The extracellular space is corrected for using a paracellular marker like [³H]-Mannitol.

- Materials:

- Krebs or Ringer buffer (pH 7.4)

- [¹⁴C(U)]-D-glucose (e.g., 370 Bq/µl)

- [³H(N)]-D-Mannitol (e.g., 370 Bq/µl)

- Phlorizin (specific SGLT1 inhibitor)

- Scintillation counter

- Procedure:

- Sac Preparation: Euthanize the animal following approved ethical guidelines. Immediately excise the small intestine and swiftly dissect the jejunum section. Flush with ice-cold oxygenated Krebs buffer to remove luminal contents.

- Sac Formation: Evert the jejunal segment and tie off one end. Carefully inject oxygenated Krebs buffer containing the experimental substrates into the sac, then tie off the other end to create a closed sac.

- Incubation: Incubate sacs in oxygenated Krebs buffer containing:

- Test condition: [¹⁴C]-Glucose + [³H]-Mannitol

- Control condition: [¹⁴C]-Glucose + [³H]-Mannitol + 0.5 mM Phlorizin

- Termination: After a set time (e.g., 15 minutes), quickly remove sacs and rinse thoroughly in ice-cold buffer to halt transport and remove adherent fluid.

- Sample Processing: Digest tissue segments or extract radioactivity. Measure ¹⁴C and ³H radioactivity in a liquid scintillation counter.

- Calculation: Calculate tissue-retained glucose by subtracting the [³H]-Mannitol space (extracellular volume) from the total [¹⁴C]-Glucose counts. The phlorizin-sensitive component represents SGLT1-specific uptake.

Protocol 2: Functional Analysis of SGLT1 and Na+/K+-ATPase Using the Ussing Chamber

This electrophysiological approach directly measures the real-time, electrogenic activity of SGLT1 [2] [7].

- Objective: To assess the functional activity of SGLT1 and its dependence on the Na+ gradient established by Na+/K+-ATPase.

- Principle: SGLT1 cotransports Na+ with glucose, generating a current. This glucose-induced change in short-circuit current (ΔIsc) is a direct measure of SGLT1 activity. Ouabain, a Na+/K+-ATPase inhibitor, ablates the Na+ gradient and thus inhibits this current.

- Materials:

- Ussing chamber system

- Data acquisition software

- D-glucose

- Ouabain

- Procedure:

- Tissue Mounting: Following euthanasia, swiftly remove the jejunum. Strip the outer muscle layers to obtain a mucosa-submucosa preparation. Mount the tissue between the two halves of the Ussing chamber, exposing the mucosal and serosal surfaces to separate reservoirs of oxygenated Ringer's solution.

- Baseline Measurement: Under short-circuit conditions, monitor the baseline Isc and transepithelial resistance until stable.

- Glucose Stimulation: Add D-glucose (e.g., 10-50 mM) to the mucosal reservoir. The rapid increase in Isc (ΔIsc) corresponds to SGLT1-mediated electrogenic Na+ transport.

- Inhibition of Na+/K+-ATPase: To confirm the role of the Na+ gradient, add ouabain (e.g., 1 mM) to the serosal reservoir. The subsequent decay of Isc demonstrates the dependence of SGLT1 on Na+/K+-ATPase activity.

Regulatory Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Glucose absorption is dynamically regulated by dietary status and hormonal signals, which can significantly impact experimental outcomes in ex vivo preparations.

- Fasting and Feeding: Fasting for 24-48 hours robustly upregulates glucose-induced Isc (SGLT1 activity) in the mouse jejunum compared to the fed state. Conversely, a high-glucose diet can suppress jejunal SGLT1 activity [2].

- Ion Channel Modulation: The membrane potential of enterocytes, set by K+ channels (e.g., KCNQ1), provides the electrical driving force for SGLT1. Inhibition of these K+ channels causes membrane depolarization and reduces SGLT1 activity [7].

- Cytosolic Calcium: Changes in cytosolic Ca²+ levels ([Ca²+]cyt) can regulate both SGLT1 and GLUT2 activity, linking glucose absorption to various signaling pathways [7].

The following table provides a toolkit of key reagents for modulating these transporters in experimental settings.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Investigating Glucose Transport

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Experimental Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phlorizin | High-affinity, competitive SGLT1 inhibitor [6] | To isolate the SGLT1-specific component of glucose uptake. Typically used at 0.1-0.5 mM. | Distinguishes active (SGLT1) from passive/diffusive components. |

| Ouabain | Specific inhibitor of Na+/K+-ATPase [12] | To collapse the transcellular Na+ gradient. Confirms SGLT1 dependence on the Na+ pump. Serosal application in Ussing chamber. | Leads to a slow decay of SGLT1-mediated Isc. |

| α-Methyl-D-glucopyranoside (AMG) | Non-metabolizable SGLT1 substrate [2] | To measure SGLT1 transport activity without interference from intracellular metabolism. | Ideal for flux studies using radiolabeled ¹⁴C-AMG. |

| GLUT2 Knockout Mice | Genetic model lacking functional GLUT2 [6] | To investigate the essentiality of GLUT2 in basolateral glucose efflux and overall absorption. | These mice are viable but exhibit glucose homeostasis defects. |

| K+ Channel Blockers (e.g., Chromanol 293B) | Inhibitors of KCNQ1 K+ channels [7] | To study the role of membrane potential in driving SGLT1 activity. | Blockers cause membrane depolarization and reduce glucose absorption. |

The ex vivo jejunal sac model provides a powerful system for deconstructing the complex, coordinated functions of SGLT1, GLUT2, and Na+/K+-ATPase. A rigorous experimental approach, utilizing the specific inhibitors, substrates, and genetic models outlined in this note, allows researchers to dissect the contribution of each transporter to overall glucose absorption. Understanding these mechanisms and their regulation is not only critical for basic physiology but also for identifying novel therapeutic targets for metabolic disorders such as diabetes and obesity.

The understanding of intestinal glucose absorption was fundamentally transformed by the work of Robert K. Crane. In August 1960, at a symposium in Prague, Crane presented for the first time his sodium-gradient hypothesis, proposing that the active transport of glucose across the intestinal mucosa is directly coupled to the flow of sodium ions down its electrochemical gradient [13] [14]. This pioneering concept of cotransport was the first proposal of flux coupling in biology and provided the physiological foundation for oral rehydration therapy (ORT), a treatment that saves millions of lives annually from diarrheal diseases [13]. This Application Note details the core principles of Crane's hypothesis and provides modern experimental protocols for investigating sodium-dependent glucose uptake in ex vivo jejunal sac models, a cornerstone technique in nutrient transport research and drug discovery.

The elegance of Crane's model lies in its explanation of how glucose accumulation occurs against its concentration gradient. The energy is derived not from ATP directly, but from the sodium electrochemical gradient across the apical membrane of the enterocyte. This gradient is established and maintained by the basolateral Na+/K+-ATPase (sodium-potassium pump), which actively pumps sodium out of the cell into the serosal space, thereby maintaining a low intracellular sodium concentration [13] [14]. The coupling of glucose movement to this "downhill" sodium flow provides the driving force for "uphill" glucose transport.

Core Mechanistic Principles

The cellular model of sodium-glucose cotransport, as established by Crane and later refined, involves a coordinated process across the enterocyte membranes [13] [14]:

- Apical Influx via SGLT1: At the brush border membrane (lumen-facing), the sodium-glucose linked cotransporter 1 (SGLT1) binds both sodium and glucose simultaneously. Utilizing the energy from the inward sodium gradient, it undergoes a conformational change to transport these substrates into the cell. The stoichiometry for SGLT1 is 2 Na+ ions : 1 glucose molecule, making the process electrogenic and sensitive to the membrane potential [14].

- Basolateral Efflux via GLUT2: The glucose accumulated inside the cell exits across the basolateral membrane into the bloodstream via the facilitative glucose transporter 2 (GLUT2), moving down its concentration gradient [13].

- Maintenance of Ion Gradients: The Na+/K+-ATPase on the basolateral membrane continuously pumps sodium out to maintain the transmembrane sodium gradient, a process that consumes ATP and links the overall process to cellular energy status [13] [14]. Potassium ions, pumped into the cell, are recycled via basolateral potassium channels, helping to maintain the negative intracellular membrane potential that further drives sodium entry.

Table 1: Key Molecular Components in Sodium-Dependent Glucose Absorption

| Component | Gene | Cellular Localization | Primary Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT1 | SLC5A1 [14] | Apical Membrane [14] | Na+-coupled glucose uptake | 2 Na+ : 1 Glucose coupling; Electrogenic; High glucose affinity [14] |

| GLUT2 | SLC2A2 [13] | Basolateral Membrane [13] | Facilitated glucose efflux | Concentration gradient-driven; High capacity |

| Na+/K+ ATPase | ATP1A1, etc. [14] | Basolateral Membrane [14] | Maintains Na+/K+ gradients | Pumps 3 Na+ out, 2 K+ in; ATP-dependent [14] |

The following diagram illustrates the coordinated interplay of these transporters and ion channels in an enterocyte, enabling efficient glucose absorption.

Quantitative Foundations & Key Evidence

Crane's hypothesis is robustly supported by decades of experimental evidence. Key quantitative findings that validate the model are summarized in the table below. These data points are critical for researchers to understand the expected magnitude of effects and for designing experiments with appropriate positive and negative controls.

Table 2: Key Experimental Evidence Supporting Crane's Hypothesis

| Experimental Observation / Parameter | System | Quantitative Outcome / Value | Biological Significance & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Na+ Dependence of Glucose Influx | Human Jejunal Epithelium [15] | Influx with Na+: 4.41 µmole/hr/cm²\nInflux without Na+: 1.65 µmole/hr/cm² | A >60% reduction in glucose uptake in Na+-free medium provides direct evidence for Na+-dependence. |

| Steady-State Glucose Accumulation | Human Jejunal Epithelium [15] | C/M* in Ringer: 3.97\nC/M with Ouabain: 1.63\nC/M in Na+-free: 0.99 | The accumulation of glucose against a gradient (C/M >1) is abolished by inhibiting the Na+ gradient (via ouabain) or removing Na+. |

| Electrogenic Transport (Short-Circuit Current, Isc) | Human Jejunal Epithelium [15] | Kt for glucose-induced Isc: ~8.01 mM | Glucose transport generates a measurable electrical current, confirming electrogenicity. The Kt indicates transporter affinity. |

| Regional Specificity in Mice | Mouse Jejunum (Fasted) [2] | Robust glucose-induced Isc after 24-48h fasting. | SGLT1-mediated glucose absorption is dynamically regulated and can be segment-specific, a key consideration for experimental design. |

| Inhibitor Specificity | Various [13] [16] | 100% inhibition of SGLT1-mediated uptake by 0.1-0.3 mM Phloridzin. | Phloridzin is a potent and specific competitive inhibitor of SGLT1, serving as an essential negative control. |

*C/M = Cellular to Medium concentration ratio.

Experimental Protocols: Ex Vivo Jejunal Sac Preparation

This section provides a detailed methodology for assessing sodium-dependent glucose uptake using an ex vivo everted jejunal sac model, a classic and powerful technique for direct investigation of transporter function.

Materials & Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Jejunal Sac Assays

| Reagent / Solution | Composition / Preparation | Primary Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygenated Krebs-Ringer Bicarbonate (KRB) Buffer | 119 mM NaCl, 21 mM NaHCO₃, 2.4 mM K₂HPO₄, 0.6 mM KH₂PO₄, 1.2 mM CaCl₂, 1.2 mM MgCl₂, 0.5 mM L-glutamine [2]. Gas with 95% O₂/5% CO₂ to pH 7.4. | Physiological saline for tissue incubation, providing ions, pH buffering, and oxygenation. |

| Na+-Free Buffer | Replace NaCl and NaHCO₃ in KRB with equimolar Choline Chloride and KHCO₃. Maintain osmolarity with mannitol. | Critical control to demonstrate Na+-dependence of glucose uptake. |

| D-Glucose Stock Solution | 1 M D-Glucose in KRB or Na+-Free buffer. Filter sterilize. | Substrate for SGLT1 transport activity. |

| Phloridzin Stock Solution | 10 mM Phloridzin in DMSO. Final working concentration typically 0.1-0.3 mM [13]. | Specific, competitive inhibitor of SGLT1; used to confirm transporter-specific uptake. |

| Ouabain Stock Solution | 1 mM Ouabain in water. | Inhibitor of basolateral Na+/K+-ATPase; used to dissipate the Na+ gradient indirectly. |

| Radioactive or Non-Radiometric Tracer | 14C-labeled D-glucose or a non-metabolizable analog like 14C-Methyl-α-D-Glucopyranoside (14C-MGP) [2]. | Allows for precise quantification of glucose flux across the intestinal tissue. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

The following diagram outlines the key stages of the everted jejunal sac experiment, from tissue preparation to data analysis.

Protocol Steps:

Tissue Preparation:

- Euthanize the animal according to approved ethical guidelines.

- Immediately perform a midline laparotomy to expose the gastrointestinal tract.

- Excise the entire small intestine and place it in ice-cold, oxygenated KRB buffer.

- Identify the jejunum (typically the proximal two-fifths of the small intestine following the duodenum).

- Gently flush the lumen with cold KRB to remove intestinal contents.

- Cut the jejunum into segments of 3-4 cm in length.

- Carefully evert each segment using a slender rod or blunt needle, turning the mucosal surface outward. Tie off one end with suture silk to create a sac.

Incubation & Experimental Conditions:

- Fill the everted sac (serosal side) with a small volume (e.g., 0.5 mL) of oxygenated KRB buffer containing the tracer and/or experimental compounds.

- Tie off the top end to create a closed sac.

- Immerse each sac in a separate flask or vial containing 10-20 mL of oxygenated incubation buffer (mucosal side) at 37°C. The mucosal incubation buffer will define the experimental condition (see Table 3).

- Incubate the sacs for a predetermined time (e.g., 15-30 minutes) with continuous oxygenation and gentle shaking.

Sample Collection & Analysis:

- After incubation, quickly remove the sacs from the media, rinse in ice-cold Na+-free buffer to stop transport and remove adherent radioactivity/nutrient.

- Gently blot the sacs on filter paper to remove excess moisture and weigh them.

- For radioactive tracers, open the sac and collect the serosal fluid. Digest the sac tissue itself (e.g., in Soluene). Quantify the radioactivity in the serosal fluid and the tissue using a liquid scintillation counter.

- For non-radiometric methods, analyze glucose concentration in the serosal fluid and/or tissue homogenates via glucose oxidase assay or HPLC.

Data Calculation:

- Calculate the glucose uptake or transfer. A common metric is the Serosal-to-Mucosal (S/M) ratio of tracer concentration or the accumulated glucose per unit tissue weight per time.

- Key Interpretation: A high S/M ratio (>1) in the complete KRB condition indicates active transport. A significant reduction in this ratio in Na+-free buffer or with phloridzin confirms the involvement of SGLT1-mediated, Na+-dependent transport.

Application in Modern Research & Drug Discovery

The principles of Crane's hypothesis remain central to modern physiological and pharmacological research. The ex vivo jejunal sac protocol is a vital tool for:

- Investigating Transport Plasticity: Studies show that SGLT1 expression and function are dynamically regulated by factors such as fasting and diet, with robust glucose transport induction observed in the jejunum of fasted mice [2]. This model is ideal for studying such regulatory mechanisms.

- Evaluating Therapeutic Agents: The model is extensively used to screen and characterize compounds that modulate glucose absorption. For example, extracts from plants like Lannea edulis and Myrtle Berry Seeds have been shown to inhibit jejunal glucose absorption, revealing a potential mechanism for their anti-diabetic properties [5] [17].

- Validating Molecular Targets: The protocol provides a functional readout for genetically modified animal models (e.g., SGLT1 knockout mice) to confirm phenotypic changes in glucose absorption [16].

In drug discovery, the SGLT family, particularly SGLT2, has become a major therapeutic target. SGLT2 inhibitors (gliflozins) are now widely used to treat Type 2 Diabetes by blocking renal glucose reabsorption, promoting glucosuria, and lowering blood glucose levels [14]. The intestinal SGLT1 remains a target for managing postprandial hyperglycemia, with dual SGLT1/2 inhibitors under investigation [17] [14]. The ex vivo jejunal sac preparation serves as a primary screen for assessing the potency and specificity of novel SGLT1 inhibitors intended for such applications.

The jejunum, as the primary site for nutrient absorption in the small intestine, possesses a highly specialized mucosa characterized by projections of villi and invaginations of crypts. These structural features dramatically increase the intestinal surface area, facilitating efficient nutrient uptake. Villus height, crypt depth, and the resulting villus-to-crypt ratio (VCR) and villus surface area (VSA) are established morphological metrics that serve as indirect indicators of intestinal health and absorptive capacity [18] [19]. Within the context of ex vivo research using jejunal sacs, understanding these morphological parameters is paramount. They provide the anatomical context for interpreting functional data on glucose absorption rates. This application note details the standardized protocols for the morphometric assessment of jejunal morphology and integrates these measures with functional glucose absorption studies, providing a comprehensive toolkit for researchers in pharmacology and drug development.

Quantitative Morphometric Data

The following tables consolidate key morphometric parameters from recent studies, providing reference data on jejunal morphology under various physiological and experimental conditions.

Table 1: Jejunal Morphometric Parameters in Avian Models (Broilers)

| Parameter | Impact of Early Feeding (Day 7) | Impact of Late Feeding (Day 35) | Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Villus Height (VH) | Increased | No significant difference | Greatest increase occurs in first week post-hatch | [18] |

| Crypt Depth (CD) | Initially increased | Decreased on D21 and D35 | Initial increase suggests higher cell turnover | [18] |

| Villus-to-Crypt Ratio (VCR) | No influence from D7 onward | No significant difference | Considered a key indicator of functional maturity | [18] |

| Villus Surface Area (VSA) | Significantly increased | Effects did not persist | Early nutrition has transient beneficial effect | [18] |

| Goblet Cell Number | No difference | No difference in jejunum | Ileum showed differences on D21 and D35 | [18] |

Table 2: Morphometric and Functional Correlations in Jejunal Studies

| Experimental Model | Morphological Change | Functional Correlation | Implication for Research | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eimeria Challenge (Broilers) | ↑Villus Width, ↑Crypt Depth, ↓VH:CD, ↓VAS | Positively correlated with worse Feed Conversion Ratio (FCR) | A larger villus is not always related to better function; inflammation must be assessed. | [19] |

| Fasting vs. Feeding (Mice) | N/A | Glucose-induced current (Isc) suppressed in jejunum of fed mice; robust in fasted mice. | SGLT1-mediated absorption is segment-specific and highly regulated by nutritional status. | [2] |

| L. edulis Extract (Diabetic Rats) | N/A | Significantly decreased glucose absorption in everted rat jejunum. | Highlights how test compounds can directly modulate absorption independent of morphology. | [5] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardized Histomorphometry of Jejunal Tissue

This protocol outlines the steps for processing and analyzing jejunal tissue to obtain quantitative morphometric data, essential for correlating structure with function in absorption studies.

Materials and Reagents:

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), ice-cold

- 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS

- Ethanol series (70%, 95%, 100%)

- Paraffin embedding system

- Microtome

- Microscope slides

- Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stain

- Light microscope with digital camera and image analysis software (e.g., NIS-Elements, ImageJ)

Procedure:

- Tissue Collection and Fixation: Immediately after euthanasia, excise a defined segment of the jejunum (e.g., 2 cm in length). Flush the lumen gently with ice-cold PBS to remove contents. Open the tissue longitudinally and immerse in 4% PFA for 24 hours at 4°C.

- Tissue Processing and Sectioning: Dehydrate the fixed tissue through a graded series of ethanol, clear with xylene or a non-polar solvent, and embed in paraffin [20]. Section the paraffin-embedded blocks at a thickness of 4–5 µm using a microtome [18] [20].

- Staining: Mount sections on slides and perform standard H&E staining to differentiate the villi, crypts, and underlying tissue layers [18].

- Image Acquisition and Morphometric Analysis: Examine slides under a light microscope. Capture digital images of intact, vertically oriented villi. For each sample, measure at least 10 well-oriented villi and crypts [21].

- Villus Height (VH): Measure from the villus tip to the villus-crypt junction.

- Crypt Depth (CD): Measure from the villus-crypt junction to the base of the crypt.

- Villus Width (VW): Measure at the base or midpoint of the villus.

- Calculate: Villus Surface Area (VSA) and Villus-to-Crypt Ratio (VCR) [18].

Protocol 2: Functional Glucose Absorption Using Everted Jejunal Sacs

This protocol describes the classic everted gut sac technique, an ex vivo model for directly measuring intestinal absorption kinetics, which can be correlated with morphometric data from the same tissue source.

Materials and Reagents:

- Krebs-Ringer Bicarbonate (KRB) buffer, oxygenated (95% O₂ / 5% CO₂)

- Glucose transport solution (e.g., KRB with specific glucose concentration)

- Aqueous plant extracts or compounds for testing (e.g., Lannea edulis extract [5])

- Surgical instruments (fine scissors, forceps)

- Water bath maintained at 37°C

- Oxygenation system (carbogen gas)

- Silicone tubing or butterfly needles

Procedure:

- Tissue Preparation: Euthanize the animal and rapidly expose the abdominal cavity. Identify and excise the entire small intestine. Flush with ice-cold, oxygenated KRB buffer. Gently evert the jejunal segment over a glass rod or silicone tubing.

- Sac Preparation and Incubation: Cut the everted jejunum into segments of 3–4 cm in length. Tie off one end of each segment, fill it with a known volume (e.g., 0.5 mL) of serosal fluid (glucose-free KRB), and tie off the other end to create a sealed sac [5]. Weigh the sac to determine tare weight.

- Experimental Incubation: Immerse each sac in a separate flask containing 50 mL of mucosal solution (oxygenated KRB buffer with glucose and/or test compounds) in a 37°C water bath with continuous oxygenation [5].

- Sample Collection and Analysis: At defined time points (e.g., 30, 60, 90 minutes), remove the sacs, gently blot, and re-weigh. Carefully puncture the sac and collect the serosal fluid. Analyze the serosal fluid for glucose concentration using a glucose assay kit or HPLC. Calculate the rate of glucose transport.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Jejunal Morphology and Absorption Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Experiment | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E) | General histological staining to visualize tissue architecture, villi, and crypts. | Standard morphometric analysis [18]. |

| 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Cross-linking fixative that preserves tissue morphology for histology. | Tissue fixation prior to embedding and sectioning [21]. |

| Krebs-Ringer Bicarbonate (KRB) Buffer | Physiological salt solution providing ionic and pH balance for ex vivo tissue viability. | Main buffer for everted gut sac and Ussing chamber experiments [5] [2]. |

| SGLT1 Inhibitors (e.g., Phloridzin) | Specific, high-affinity competitive inhibitor of the Sodium-Glucose Transporter 1 (SGLT1). | To confirm and quantify the active, carrier-mediated component of glucose absorption [2]. |

| L. edulis Aqueous Extract | Plant extract demonstrated to reduce intestinal glucose absorption. | Used as an example interventional compound to modulate absorption function [5]. |

| 3D Tissue Clearing Reagents (CUBIC) | Renders intact tissues transparent for deep imaging. | Enables 3D reconstruction of intestinal villi and crypts beyond traditional 2D histology [21]. |

Integrated Experimental Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow connecting jejunal tissue preparation, parallel morphological and functional analyses, and integrated data interpretation.

The integration of detailed jejunal morphometry with robust functional assays like the everted gut sac technique provides a powerful approach for evaluating nutrient absorption mechanisms. As demonstrated, morphological data on villus structure must be interpreted with caution, as increases in size do not always correlate with improved function, particularly under inflammatory conditions [19]. Furthermore, functional absorption is dynamically regulated by factors such as nutritional status, which can dictate transporter activity independent of structural changes [2]. The standardized protocols and reference data provided herein offer a framework for researchers in drug discovery and development to systematically investigate how new chemical entities, biologics, or natural extracts influence intestinal health and function, thereby strengthening the predictive power of ex vivo models.

The choice of animal model is a fundamental consideration in gastrointestinal research, profoundly influencing the translational value of experimental data on nutrient absorption. Ex vivo studies using jejunal sacs provide a powerful tool for investigating intestinal glucose transport mechanisms while preserving native tissue architecture and cellular polarity. However, interspecies variations in anatomy, transporter expression, and regulatory physiology can significantly impact research outcomes. This application note examines the key similarities and differences between murine, avian, and human intestinal models to inform experimental design and data interpretation in glucose absorption studies. Understanding these species-specific characteristics is essential for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to extrapolate findings from preclinical models to human physiology and disease states, particularly in the context of metabolic disorders and therapeutic development.

Comparative Physiology of Intestinal Glucose Absorption

Fundamental Transport Mechanisms

Glucose absorption across the intestinal epithelium occurs through multiple coordinated pathways, with significant species-specific variations in their relative contributions:

Active Transcellular Transport: The sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1) located in the apical membrane of enterocytes mediates active glucose uptake against its concentration gradient, utilizing the sodium electrochemical gradient maintained by Na+/K+ ATPase [22] [2]. This secondary active transport is complemented by facilitated diffusion via GLUT2 transporters at the basolateral membrane [22].

Paracellular Passive Transport: Passive glucose diffusion through tight junctions between epithelial cells contributes significantly to total absorption, particularly at high luminal glucose concentrations [22]. Research using vascularly perfused rat intestine demonstrates that approximately 30% of glucose absorption persists even after combined SGLT1 and GLUT2 blockade, indicating a substantial paracellular component [22].

Adaptive Regulation: Intestinal glucose transport exhibits dynamic regulation in response to nutritional status. Fasting robustly enhances SGLT1-mediated glucose absorption in the mouse jejunum, while feeding suppresses it, demonstrating segment-specific adaptation mechanisms for efficient glucose handling [2].

Species-Specific Comparison of Jejunal Glucose Handling

Table 1: Comparative Glucose Absorption Characteristics Across Species

| Characteristic | Mouse Models | Avian Models (Chick) | Human |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Absorption Site | Jejunum > Ileum [2] | Jejunum (embryonic development studied) [23] | Jejunum > Ileum [24] |

| SGLT1 Expression Pattern | Fasting increases jejunal expression [2] | Thyroxine and hydrocortisone influence developmental appearance [23] | Highest in proximal jejunum [24] |

| Paracellular Contribution | Significant, especially in proximal intestine [22] | Limited data available | Present, quantitative significance debated |

| Regional Specificity | Strong functional differentiation along duodenal-ileal axis [2] | Limited data available | Marked jejunal-ileal differences [24] |

| Dipeptide Transport | Not applicable | Not applicable | Comparable jejunal and ileal absorption [24] |

| Regulatory Pathways | FFA1/GPR40 mediated inhibition [25] | Limited data available | Complex endocrine regulation |

Table 2: Functional Differences in Jejunal versus Ileal Absorption in Humans

| Absorbed Compound | Jejunal Absorption | Ileal Absorption |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Faster absorption [24] | Slower absorption [24] |

| Glycine | Faster absorption [24] | Slower absorption [24] |

| L-alanine | Faster absorption (5 of 6 subjects) [24] | Slower absorption |

| Glycyl-L-alanine (dipeptide) | Comparable absorption rate [24] | Comparable absorption rate [24] |

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Murine Models: Workhorses of Intestinal Glucose Research

Murine models offer significant advantages for intestinal glucose absorption studies, including genetic tractability, relatively low maintenance costs, and well-characterized physiology. Several key methodological approaches have been developed:

Everted Jejunal Sac Protocol: This classic technique involves inverting intestinal segments to directly expose the mucosal epithelium to experimental solutions, allowing precise measurement of nutrient transport. The method preserves native epithelial structure and transporter localization while enabling controlled experimental conditions [25].

Vascularly Perfused Intestine Preparation: This sophisticated approach maintains intestinal viability by perfusing the vascular bed, preserving the tissue's polar organization and complete transport pathways from lumen to circulation. Studies using this method have demonstrated non-saturable glucose absorption components even at high luminal concentrations (up to 1100 mmol/L), suggesting significant diffusive transport mechanisms [22].

Ussing Chamber Measurements: This technique enables precise electrophysiological assessment of electrogenic transport processes by measuring glucose-induced short-circuit current (Isc) across mounted intestinal mucosa. Research using Ussing chambers has revealed that SGLT1-mediated glucose absorption is minimal in the jejunum of ad libitum-fed mice but robustly enhanced after 24-48 hours of fasting [2].

Avian Models: Insights from Embryonic Development

Avian models, particularly chick embryos, provide unique opportunities for studying the developmental aspects of intestinal glucose transport:

Hormonal Regulation of Transport Development: Embryonic chick intestine demonstrates that thyroxine and hydrocortisone significantly influence the developmental appearance of glucose active transport capabilities, providing insights into the endocrine regulation of intestinal maturation [23].

Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) Effects: Studies in avian models and mice have shown that EGF enhances jejunal glucose absorption, suggesting conserved regulatory mechanisms across species [23].

Human Tissue: The Gold Standard for Translation

Human intestinal tissue remains the reference standard for validating findings from animal models, though access is limited:

Regional Functional Specialization: Perfusion studies in human subjects confirm that glucose absorption occurs more rapidly in the jejunum than ileum, highlighting important regional specialization [24].

Dipeptide Transport Significance: Unlike amino acid and glucose absorption, dipeptide transport demonstrates comparable rates between jejunum and ileum in humans, emphasizing the importance of oligopeptide transport pathways, particularly in the distal intestine [24].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Everted Jejunal Sac Preparation for Glucose Uptake Studies

Principle: This ex vivo technique measures radiolabeled glucose analog uptake by intestinal tissue, preserving mucosal architecture and transporter function while enabling controlled pharmacological manipulation.

Reagents Required:

- Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer (pH 7.4)

- Oxygen gas mixture (95% O2/5% CO2)

- 3-O-methyl-glucose [3H] (3-OMG) or 14C-d-glucose

- Pharmacological agents of interest (e.g., phlorizin, delphinidin, receptor antagonists)

- Scintillation cocktail for radioactivity measurement

Procedure:

- Euthanize the animal according to approved ethical guidelines and immediately expose the abdominal cavity.

- Gently excise the entire small intestine and place it in oxygenated ice-cold Krebs-Ringer buffer.

- Identify the jejunal segment (typically 10-15 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz in humans or corresponding region in rodents).

- Gently flush the lumen with cold buffer to remove intestinal contents.

- Evert the jejunal segment carefully over a glass rod or using fine forceps, exposing the mucosal surface outward.

- Cut the everted intestine into 2-3 cm segments and tie off one end of each segment.

- Fill the sacs with oxygenated buffer containing appropriate experimental treatments.

- Tie off the opposite end to create closed sacs containing the serosal solution.

- Incubate sacs in oxygenated buffer containing radiolabeled glucose analogs (e.g., 3-OMG or 14C-d-glucose) at 37°C with continuous oxygenation.

- Maintain appropriate controls, including phlorizin (1 mM) as an SGLT1 inhibitor control.

- After designated time points (typically 5-15 minutes), remove sacs and rapidly rinse in ice-cold buffer to stop transport.

- Digest tissue or extract solutes to measure accumulated radioactivity by scintillation counting.

- Normalize glucose uptake to tissue protein content or dry weight.

Applications: This protocol is ideal for investigating transporter kinetics, pharmacological inhibition (e.g., delphinidin effect via FFA1 [25]), and comparative absorption between intestinal regions or experimental conditions.

Vascularly Perfused Rat Intestine Model

Principle: This advanced preparation maintains intestinal viability by perfusing the vascular bed, enabling study of complete transport pathways from lumen to circulation and their relationship with endocrine secretion [22].

Procedure:

- Anesthetize the animal and cannulate the superior mesenteric artery and vein.

- Gently isolate an intestinal segment while preserving vascular connections.

- Perfuse the vascular bed with oxygenated physiological solution containing appropriate substrates.

- Introduce glucose solutions into the luminal compartment.

- Measure glucose appearance in the venous effluent using radioactive tracers (14C-d-glucose) or sensitive glucose assays.

- Apply specific transporter inhibitors (phlorizin for SGLT1, phloretin for GLUT2) to determine relative contributions of different pathways.

- Calculate absorption rates from arteriovenous concentration differences and flow rates.

Key Findings Using This Model:

- Glucose absorption involves both SGLT1/GLUT2-mediated transport and a significant paracellular component (~30% of total absorption) [22].

- Paracellular glucose absorption is greater in proximal than distal small intestine [22].

- SGLT1 blockade unexpectedly enhances paracellular mannitol absorption, suggesting transporter interactions with junctional permeability [22].

Signaling Pathways in Intestinal Glucose Absorption

Free Fatty Acid Receptor 1 (FFA1/GPR40) Signaling

Research has identified a novel signaling pathway through which the anthocyanidin delphinidin modulates intestinal glucose absorption:

- Receptor Activation: Delphinidin binds to and activates FFA1 receptors on intestinal epithelial cells, as demonstrated in HT-29 and Caco-2 cell lines [25].

- Calcium Signaling: FFA1 activation triggers phospholipase C-mediated IP3 production, leading to calcium release from intracellular stores followed by store-operated calcium entry [25].

- Transport Modulation: The resulting increased intracellular calcium concentration inhibits SGLT1-mediated glucose transport, reducing jejunal glucose absorption in mice [25].

- Physiological Significance: This pathway represents a local mechanism for regulating intestinal glucose absorption independent of incretin hormones, potentially contributing to the antidiabetic effects of anthocyanin-rich foods.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Intestinal Glucose Absorption Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transport Inhibitors | Phlorizin (1 mM) [22] [25] | Selective SGLT1 inhibition | Distinguishes active vs. passive transport components |

| Phloretin (1 mM) [22] | GLUT2 blockade | Assesses basolateral transport contribution | |

| FFA1/GPR40 Modulators | Delphinidin (100 μM) [25] | Natural FFA1 agonist | Inhibits glucose uptake via calcium signaling |

| TAK-875 [25] | Synthetic FFA1 agonist | Positive control for receptor activation | |

| DC260126, GW1100 (10 μM) [25] | FFA1 antagonists | Confirms receptor-specific effects | |

| Signaling Modulators | BAPTA-AM (50 μM) [25] | Intracellular calcium chelation | Tests calcium dependence |

| LY294002 (10 μM) [25] | PI3K pathway inhibition | Assesses kinase involvement | |

| Cell Line Models | Caco-2 cells [26] [25] | Human intestinal epithelial model | Expresses FFA1, useful for mechanistic studies |

| HT-29 cells [25] | Human enterocytic line | Shows calcium response to delphinidin | |

| Radiolabeled Tracers | 14C-d-glucose [22] | Glucose absorption quantification | Sensitive detection in vascular perfused models |

| 3-O-methyl-glucose [3H] [25] | Non-metabolizable glucose analog | Measures transport independent of metabolism |

Species-specific differences in intestinal glucose absorption mechanisms present both challenges and opportunities for research design. Murine models offer experimental tractability but demonstrate important distinctions in transporter regulation and paracellular contribution. Avian models provide unique insights into developmental aspects of transport function. Human tissue remains the reference standard but has limited availability. The emerging understanding of local regulatory pathways, such as FFA1-mediated modulation of glucose absorption, highlights the complexity of intestinal nutrient sensing and transport regulation. Researchers should carefully consider these species-specific characteristics when designing experiments and extrapolating findings across models, particularly in the context of drug development and therapeutic targeting of intestinal glucose handling mechanisms.

Mastering the Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide to the Everted Sac Technique

Application Notes and Protocol for Ex Vivo Glucose Absorption Studies

Within investigations of intestinal glucose absorption mechanisms for drug development and metabolic research, the everted jejunal sac model serves as a fundamental ex vivo technique. This protocol details the precise preparation of viable jejunal segments, a critical prerequisite for reliable measurement of nutrient transporter function and the evaluation of compounds targeting conditions like diabetes and metabolic syndrome [27] [17]. Proper execution of the euthanasia, dissection, and eversion procedures is essential for preserving tissue integrity and ensuring the physiological relevance of subsequent functional analyses.

Materials and Reagents

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Isoflurane | Anesthetic for inducing and maintaining surgical-plane anesthesia prior to euthanasia [28]. |

| Oxygen (O₂) | Carrier gas for isoflurane during anesthesia; ensures tissue oxygenation until excision [28]. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), ice-cold | Isotonic solution used to flush intestinal lumen post-excision, removing contents and cooling the tissue to slow metabolism [28]. |

| Krebs-Ringer Bicarbonate (KRB) Buffer | Oxygenated physiological salt solution used to maintain tissue viability, provide nutrients, and serve as the medium for glucose transport assays [27]. |

| 95% O₂ / 5% CO₂ Gas Mixture | Used to carbogenate KRB buffer, maintaining physiological pH (7.4) and providing oxygen for tissue respiration during ex vivo experiments [2]. |

| SGLT1 Inhibitors (e.g., Phlorizin) | Specific pharmacological tool to confirm sodium-dependent glucose transport activity (SGLT1-mediated) in the prepared tissue [27]. |

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Animal Euthanasia and Small Intestine Excision

- Anesthesia: Place the animal (e.g., mouse or rat) in an induction chamber and anesthetize using 5% isoflurane delivered in oxygen [28]. Confirm deep anesthesia by the absence of pedal reflex.

- Terminal Procedure: While under sustained anesthesia, perform exsanguination via transcardial perfusion or direct puncture of a major vessel such as the abdominal aorta. This method is consistent with protocols approved by animal ethics committees for terminal tissue collection [28].

- Laparotomy: Immediately after confirming cessation of circulation, perform a midline laparotomy to expose the abdominal cavity.

- Intestinal Localization and Excision: Identify the stomach and the small intestine. Locate the pyloric sphincter (stomach-duodenum junction) and the ileocecal valve (small intestine-colon junction).

Dissection and Preparation of Jejunal Segments

- Tissue Handling: Place the excised small intestine into a petri dish filled with ice-cold PBS to minimize metabolic degradation.

- Lumen Flushing: Using a syringe filled with ice-cold PBS and attached to a blunt-ended needle, gently flush the lumen of the intestine to clear all digestive contents [28].

- Jejunal Segment Identification: Lay the intestine on a chilled, silicone-coated dissection dish. The jejunum is typically defined as the segment starting approximately 10-11 cm distally from the pyloric sphincter in mice [28].

- Segment Resection: Using fine dissection scissors, resect a segment of the proximal jejunum of the desired length (e.g., 1 cm to 4 cm, depending on the specific assay requirements) [27] [2].

Eversion of Jejunal Segments

- Segment Trimming: Gently blot the resected jejunal segment on moist filter paper. Trim any residual mesentery carefully to avoid damaging the intestinal wall.

- Cannulation and Securing: Slide a slender, blunt-ended rod (e.g., a thin glass rod or a polished metal probe) into the lumen of the segment. Secure one end of the segment very gently to the rod using a pre-placed silk suture.

- Eversion Procedure: Holding the free end of the suture, carefully and slowly pull the intestinal segment over the rod, turning it inside-out. This process exposes the mucosal epithelium to the external incubation medium.

- Sac Preparation (Optional): For the everted sac technique, slide the everted segment off the rod. Tie one end securely with a suture. Fill the resulting sac with a small volume (e.g., 0.3 ml) of oxygenated KRB buffer using a syringe with a fine needle [27]. Finally, tie off the other end to create a closed, fluid-filled sac ready for incubation.

Key Experimental Parameters and Data

Table 2: Quantitative Anatomical and Functional Benchmarks for Murine Jejunum

| Parameter | Value in Non-Pregnant / Control State | Value in Late-Pregnant State (GD17.5) | Notes / Method of Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total SI Weight | Baseline | ~20% heavier [28] | Weighed immediately post-excision. |

| Total SI Length | Baseline | ~10% longer [28] | Measured under slight tension on chilled surface. |

| Jejunal Villi Length | Baseline | ~18% longer [28] | Fixed tissue, histological sectioning and measurement. |

| Active Glucose Transport (Isc) | Present | Similar per unit area [28] | Measured in Ussing chamber; indicates functional capacity. |

| SGLT1 Expression | Variable by region | Increased in some regions (e.g., duodenum) [28] | Western blot of Brush Border Membrane Vesicles (BBMV) [2]. |

Workflow and Functional Validation

The following diagram illustrates the complete journey of the jejunal tissue from the animal to functional analysis, highlighting key validation steps.

Figure 1: Workflow for Jejunal Segment Preparation and Validation.

Troubleshooting and Critical Steps

- Tissue Viability: The entire process from euthanasia to placing the tissue in oxygenated buffer should be completed as rapidly as possible. Prolonged ischemia or rough mechanical handling will compromise cellular function and transporter activity.

- Eversion Technique: The eversion step is mechanically stressful. Use fine, smooth tools and perform the inversion gently and steadily. Applying excessive force can damage the epithelial layer, leading to leaky sacs and non-physiological results.

- Functional Validation: Always include control and reference samples. The functionality of the prepared sacs should be confirmed by demonstrating a significant inhibition of glucose absorption in the presence of a specific SGLT1 inhibitor like phlorizin [27]. Furthermore, consistent with findings on intestinal plasticity, researchers should account for physiological states (e.g., pregnancy, fasting) that inherently alter jejunal anatomy and molecular transporter profiles [28] [2].

In ex vivo glucose absorption measurement using jejunal sacs, the composition of the buffer solution is not merely a background medium but a critical experimental variable that directly influences physiological relevance and data reliability. The ionic environment maintains tissue viability, regulates transporter activity, and preserves mucosal integrity during experimentation. Proper buffer composition ensures that the measured glucose absorption accurately reflects in vivo physiological processes rather than artifacts of experimental conditions. This application note provides a comprehensive framework for optimizing buffer systems specifically for jejunal sac experiments, incorporating recent advances in intestinal physiology and absorption methodology.

The jejunal sac model, a well-established preparation for studying intestinal transport, involves isolating segments of the jejunum, filling them with oxygenated buffer solutions containing compounds of interest, and measuring transmural transport. The success of this technique hinges on maintaining the functional and structural integrity of the intestinal epithelium throughout the experimental timeframe, a requirement fundamentally dependent on the buffer's ionic composition, oxygenation, and physicochemical properties.

Fundamental Buffer Compositions for Jejunal Sac Experiments

Standard Physiological Buffer Formulations

The choice of buffer system significantly impacts experimental outcomes, particularly for compounds whose solubility and permeability are pH-dependent. Research demonstrates that buffer composition can cause sixfold variations in drug solubility and notable differences in effective permeability coefficients (P~app~) [29]. The following table summarizes standard physiological buffer formulations used in intestinal absorption studies:

Table 1: Composition of Standard Physiological Buffers for Intestinal Research

| Component | Krebs-Ringer Buffer (KRB) | Krebs-Henseleit Buffer | Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | 118 mM | 118 mM | 137 mM | 137 mM |

| Potassium Chloride (KCl) | 4.7 mM | 4.7 mM | 5.4 mM | 2.7 mM |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | 2.5 mM | 2.5 mM | 1.3 mM | - |

| Magnesium Sulfate (MgSO₄) | 1.2 mM | 1.2 mM | 0.8 mM | - |

| Sodium Phosphate (NaH₂PO₄/Na₂HPO₄) | 1.2 mM | 1.2 mM | 0.34 mM Na₂HPO₄ | 10 mM |

| Sodium Bicarbonate (NaHCO₃) | 25 mM | 25 mM | 4.2 mM | - |

| D-Glucose | 11 mM | 11 mM | 5.6 mM | - |

| Other Key Components | - | - | 0.44 mM KH₂PO₄ | - |

| Typical pH Range | 7.3-7.4 | 7.3-7.4 | 7.2-7.4 | 7.2-7.4 |

| Oxygenation Requirement | 95% O₂ / 5% CO₂ | 95% O₂ / 5% CO₂ | Air/CO₂ mixture | Air equilibrium |

Krebs-Ringer Buffer (KRB) is particularly well-suited for jejunal sac experiments investigating glucose absorption [27]. Its high bicarbonate concentration requires continuous carbogenation (95% O₂ / 5% CO₂) to maintain physiological pH, which simultaneously ensures optimal oxygen delivery to the tissue. The presence of divalent cations (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺) is essential for maintaining tight junction integrity, thereby controlling paracellular transport and ensuring that glucose absorption occurs primarily via the transcellular pathway.

Impact of Buffer Composition on Solute Properties

The ionic composition, pH, and buffer capacity directly influence the solubility and permeability of test compounds, which must be considered when designing experiments. A comparative study of ibuprofen demonstrated that its saturated solubility varied sixfold across eight common physiological buffers, from a low in HBSS to a high in PBS at pH 7.4 [29]. These differences were primarily attributed to final pH variations upon drug saturation and the presence of solubilizing components. Notably, Fed State Simulated Intestinal Fluid (FeSSIF), which contains bile salts and lipids, significantly enhanced solubility due to micellar solubilization, while the presence of divalent ions in Krebs buffer reduced the solubility of some anionic compounds.

Permeability results can also be buffer-dependent. The effective permeability coefficient (P~app~) of ibuprofen was significantly higher in PBS and FaSSIF compared to citrate and HBSS buffers, highlighting that buffer selection can directly influence absorption measurements [29]. Therefore, reporting exact buffer composition is crucial for reproducing experimental findings.

Advanced Optimization: Ionic and Oxygenation Parameters

Optimizing the Ionic Environment for Glucose Transport Studies

Glucose absorption in the jejunum occurs primarily via the coordinated action of the apical sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1) and the basolateral glucose transporter 2 (GLUT2). The ionic environment of the buffer directly powers this process.

- Sodium Dependence: SGLT1 is a secondary active transporter that couples glucose transport with sodium ions moving down their electrochemical gradient. The typical Na⁺ concentration in KRB (∼138 mM) maintains this critical gradient. Reduction of sodium concentration directly diminishes active glucose uptake.

- Energy Substrate: Including 11 mM D-glucose in the buffer provides an energy substrate for the tissue, helping to maintain viability during the experiment. However, for tracer studies, this may be replaced with mannitol for osmotic balance.

- Divalent Cations: Calcium (2.5 mM) and magnesium (1.2 mM) are essential for preserving tight junction integrity and cellular signaling. Their omission can increase paracellular permeability, potentially confounding glucose absorption measurements.

Recent research on dietary proteins highlights the dynamic regulation of intestinal glucose transport. Digested proteins from casein, fish gelatin, and other sources have been shown to acutely reduce glucose uptake and GLUT2 mRNA expression in enterocytes [27]. This suggests that buffer composition could be modified to investigate specific regulatory mechanisms by including protein hydrolysates or specific amino acids.

Oxygenation Strategies for Tissue Viability

The high metabolic rate of intestinal epithelium demands adequate oxygen delivery to maintain ATP-dependent processes, including active transport and cellular homeostasis.

Diagram 1: Oxygenation impact on glucose absorption.

For jejunal sac experiments, continuous oxygenation with carbogen (95% O₂ / 5% CO₂) is the gold standard [27]. The 5% CO₂ is essential for maintaining the bicarbonate buffer system at physiological pH (7.3-7.4). In experiments where bicarbonate-free buffers (e.g., PBS, HEPES) are used, alternative pH stabilization methods are available, but these systems lack the physiological buffering characteristics of the bicarbonate-CO₂ system.

It is important to distinguish this tissue-level oxygenation from systemic hyperoxia, which has been shown to disrupt gut microbiota ecology by increasing luminal oxygen availability and promoting facultative anaerobe overgrowth [30]. In ex vivo preparations, maximizing oxygen delivery to the intestinal tissue itself is paramount for maintaining viability, as the vascular system is no longer functional.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Glucose Absorption Using Jejunal Sacs

Jejunal Sac Preparation and Installation

This protocol outlines the optimized procedure for measuring ex vivo glucose absorption using rodent jejunal sacs, based on established methodologies with critical modifications for enhanced reliability [27].

Table 2: Reagent Solutions for Jejunal Sac Experiments

| Reagent/Solution | Composition/Specification | Primary Function | Notes/Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Krebs-Ringer Buffer (KRB) | As in Table 1 | Physiological maintenance medium | Must be freshly prepared; gas with carbogen for ≥20 min before use |

| Carbogen Gas | 95% O₂, 5% CO₂ | Tissue oxygenation & pH maintenance | Use medical grade; bubble continuously at low flow rate |

| D-Glucose | 10-100 mM in KRB | Absorption substrate | Concentration depends on study goals (kinetics vs. capacity) |

| Radioisotopic Tracer | ³H- or ¹⁴C-labeled glucose | Transport quantification | Follow radiation safety protocols; use minimal necessary activity |

| Anaesthetic | Isoflurane or sodium pentobarbital | Humane euthanasia | Institutionally approved protocol required |

| Antioxidant Cocktail | N-acetylcysteine (1-5 mM) | Reduction of oxidative stress | Optional for prolonged experiments |

Step 1: Animal Preparation and Tissue Harvest

- Anesthetize adult Wistar rats (200-250 g) using an institutionally approved anesthetic (e.g., isoflurane, 5% in oxygen) [28] [27].

- Following deep anesthesia, perform a midline laparotomy to access the abdominal cavity.

- Identify the proximal jejunum (starting approximately 5 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz) and carefully dissect a segment of 10-15 cm in length.

- Excise the segment and immediately place it in ice-cold, pre-oxygenated KRB to slow metabolic activity and prevent ischemic damage.

- Gently flush the luminal contents with cold KRB using a blunt-ended syringe to remove residual digesta without damaging the mucosal surface.

Step 2: Sac Preparation and Installation

- Divide the cleaned jejunal segment into individual sacs of 1 cm length using sharp surgical scissors [27].

- Carefully tie off one end of each sac with surgical silk (4-0).

- Using a fine-tipped pipette or syringe, fill each sac with 0.3 mL of oxygenated KRB containing the experimental treatment (e.g., glucose, inhibitors, protein digests) and the isotopic tracer (³H- or ¹⁴C-labeled glucose, 0.02 μCi/mL) [27].

- Tie off the proximal end to create a sealed sac. Ensure the sac is taut but not over-distended to avoid compromising blood flow to the mucosa.

- Weigh each filled sac to determine the initial mass.

Step 3: Incubation and Sampling

- Individually place sacs in 50 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 20 mL of oxygenated KRB (serosal buffer).

- Maintain the flasks in a water bath at 37°C with continuous carbogen gassing throughout the incubation period.

- Gently agitate the flasks using an orbital shaker (60-80 oscillations/minute) to ensure adequate mixing and minimize unstirred water layers.

- Following a standard incubation period (typically 60-120 minutes), remove the sacs and carefully blot them on absorbent paper.

- Weigh the sacs to determine final mass.

- Sacrifice the tissue by cutting both ends and collect the serosal fluid for analysis.

- Sac content can be recovered by puncturing the sac or washing the lumen with a known volume of buffer.

Analytical Methods and Data Calculation

Glucose Absorption Quantification:

- Measure the radioactivity in both the initial dosing solution and the collected serosal fluid using liquid scintillation counting.

- Calculate the apparent permeability coefficient (P~app~) using the following equation:

P~app~ = (dQ/dt) / (A × C₀)

where dQ/dt is the transport rate (mol/s), A is the nominal surface area of the sac (cm²), and C₀ is the initial concentration in the donor compartment (mol/mL) [29].

- Alternatively, express results as cumulative glucose transport (μmol/cm tissue/h) or percentage of dose transported.

Viability Assessment:

- Monitor tissue viability throughout the experiment by visual inspection (maintenance of pink color, absence of edema or discoloration).

- Confirm viability post-experiment by measuring lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release into the serosal buffer or using histological examination of fixed tissue samples (e.g., H&E staining).

Diagram 2: Jejunal sac experiment workflow.

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for Jejunal Sac Experiments

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Glucose Transport | Tissue non-viability, insufficient oxygenation, incorrect buffer pH, incorrect sodium concentration | Verify carbogen delivery, check pH (7.3-7.4), confirm Na⁺ concentration (~138 mM), include positive control |

| High Variability Between Sacs | Inconsistent sac preparation, regional differences along jejunum, uneven oxygenation | Use consistent sac length (1 cm), take adjacent sacs for replicates, ensure uniform gas bubbling |

| Poor Tissue Viability | Prolonged ischemia during dissection, bacterial contamination, excessive stretching | Minimize dissection time (<5 min), use ice-cold buffer during setup, include antibiotics in buffer |

| Buffer pH Drift | Inadequate CO₂ gassing, bacterial growth, outdated buffer components | Ensure tight seals on incubation vessels, use fresh buffer daily, check CO₂ concentration (5%) |

| Low Signal in Tracer Studies | Insufficient radioactive tracer, quenching in scintillation counting, tracer instability | Validate tracer concentration, use appropriate scintillation cocktail, confirm tracer purity |

Methodological Variations and Applications

The basic jejunal sac protocol can be modified to address specific research questions:

- Inhibitor Studies: To investigate specific transport pathways, include pharmacological inhibitors in the buffer. For example, phlorizin (0.1-1 mM) can be used to specifically inhibit SGLT1-mediated glucose transport [27].

- Protein Digest Co-incubation: As evidenced by recent research, digested dietary proteins (e.g., casein, fish gelatin at 5 mg/mL) can be included to study their acute effects on glucose transport and transporter expression [27].

- Mucosal vs. Serosal Sampling: While the standard protocol measures serosal-to-mucosal transport, the direction can be reversed to study secretory processes or basolateral transport mechanisms.

- Ussing Chamber Integration: For more detailed electrophysiological measurements, the jejunal sac preparation can be adapted to the Ussing chamber technique, allowing for simultaneous measurement of short-circuit current and transepithelial resistance [31].

Optimizing buffer composition and oxygenation parameters is fundamental to obtaining physiologically relevant data from ex vivo jejunal sac experiments. The ionic environment must faithfully replicate key physiological conditions—particularly sodium concentration for SGLT1-mediated glucose transport—while maintaining tissue viability through continuous carbogen gassing. The standard Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer remains the gold standard for such studies, though researchers should be aware of how specific modifications (divalent cations, pH, buffer capacity) can influence experimental outcomes.

As research advances, particularly in understanding how dietary components like protein hydrolysates regulate glucose absorption, the jejunal sac model—when coupled with precisely optimized buffer systems—continues to offer valuable insights into intestinal transport mechanisms with direct relevance to drug development and nutritional science.

The everted jejunal sac model is a classical ex vivo technique used to investigate the mechanisms and kinetics of intestinal nutrient absorption, particularly for sugars like glucose. The model involves inverting a segment of the jejunum, so that the mucosal epithelium faces outward into the incubation solution, and the serosal surface faces the inner fluid-filled sac. This configuration allows for the direct study of transepithelial transport from the mucosal solution to the serosal compartment [32] [33].

The primary mechanism for glucose absorption in the small intestine is active transport mediated by the Na+/Glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1) located on the apical membrane of enterocytes. The driving force for this transport is the sodium gradient established by the basolateral Na+/K+ ATPase pump [32]. The everted sac model is ideally suited to study this saturable, active process, as well as to investigate the effects of pharmaceuticals, plant extracts, or dietary compounds on glucose absorption capacity [5] [27]. By measuring the accumulation of glucose or its analogs in the serosal fluid over time, researchers can quantify absorption rates and elucidate transport pathways.

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential reagents and materials required for the everted jejunal sac experiment.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions in the Everted Sac Assay

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Krebs-Ringer Bicarbonate (KRB) Buffer | A physiological salt solution providing ions (Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cl-, HCO3-) to maintain tissue viability and electrophysiological function [27]. | Used as the standard incubation medium in ex vivo glucose absorption experiments with rat jejunal sacs [27]. |

| Oxygen/Carbogen Gas (95% O2 / 5% CO2) | Provides oxygenation for tissue metabolism and maintains the pH of the bicarbonate buffer at approximately 7.4 [2]. | Standard procedure for maintaining physiological conditions in Ussing chamber and organ bath studies [2]. |

| D-Glucose | The primary nutrient whose absorption kinetics are being studied. | |

| Phloridzin (Phlorizin) | A specific, competitive inhibitor of SGLT1. Used to confirm the involvement of the active SGLT1 transport pathway [32]. | Suppressed glucose-induced short-circuit current in broiler chicken jejunum, demonstrating SGLT1 activity [34]. |

| α-Methyl-D-Glucopyranoside (AMG) | A non-metabolizable analog of glucose transported by SGLT1. Used to trace glucose uptake without interference from cellular metabolism [2] [27]. | Used in Caco-2 cell uptake assays and tracer studies to measure SGLT1-mediated transport specifically [27]. |

| Lannea edulis Aqueous Extract | An example of a plant extract investigated for its ability to modulate glucose absorption, potentially via SGLT1 inhibition [5] [17]. | Significantly decreased glucose movement in the everted rat jejunum model [5]. |

Specialized Equipment

- Organ Bath or Incubation Chamber: A temperature-controlled water bath with racks to hold multiple sacs.

- Surgical Instruments: Fine scissors, forceps, and silk sutures.

- Carbogen Gas Tank and Tubing: For continuous oxygenation of the incubation medium.

- Glucometer or Glucose Assay Kit: For quantifying glucose concentration in serosal fluid samples.

Experimental Workflow

The diagram below outlines the key steps involved in preparing and conducting an everted jejunal sac experiment for measuring glucose absorption.

Detailed Protocol

Animal and Tissue Preparation