Dietary Proteins and Amino Acids in Glucose Homeostasis: Molecular Mechanisms, Clinical Applications, and Therapeutic Potential

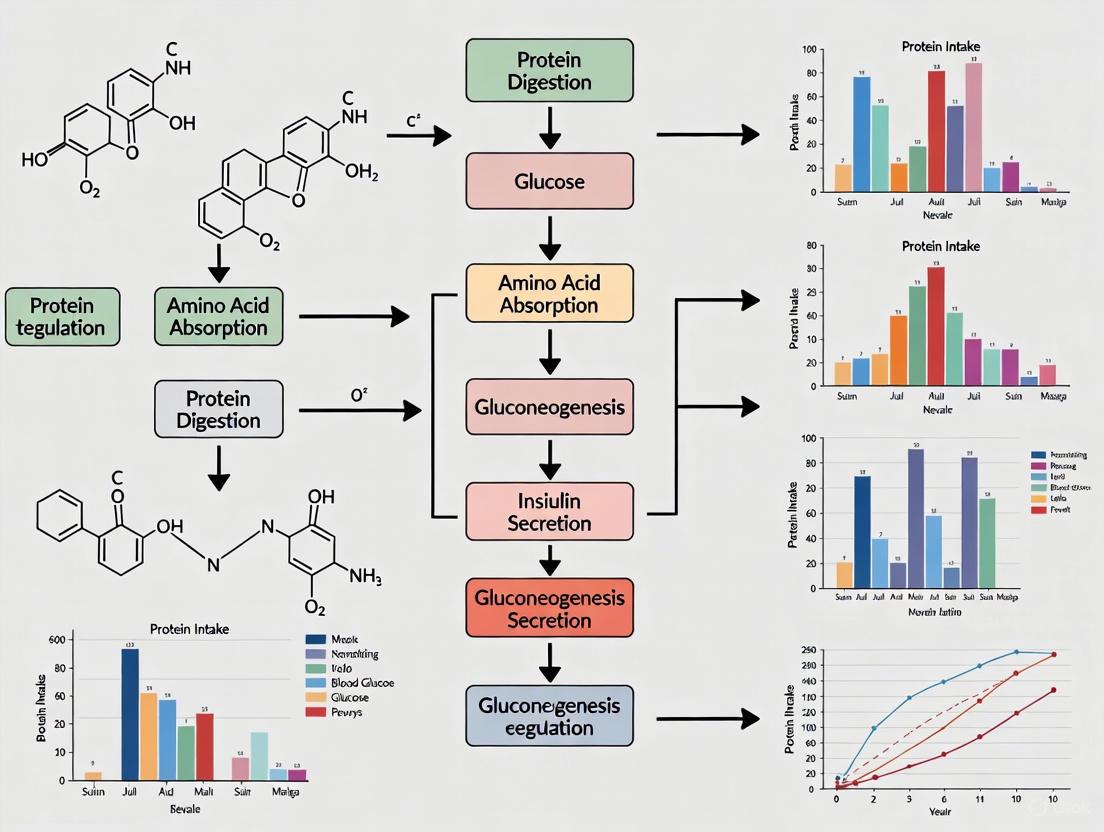

This article synthesizes current evidence on the complex, dual role of dietary proteins and amino acids in regulating glucose metabolism.

Dietary Proteins and Amino Acids in Glucose Homeostasis: Molecular Mechanisms, Clinical Applications, and Therapeutic Potential

Abstract

This article synthesizes current evidence on the complex, dual role of dietary proteins and amino acids in regulating glucose metabolism. It explores foundational mechanisms, including the activation of nutrient-sensing pathways like mTOR and the paradoxical effects of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), which can both promote insulin sensitivity and contribute to resistance. For researchers and drug development professionals, the content evaluates methodological approaches such as specialized high-protein diets and amino acid supplementation, detailing their application in weight loss, sarcopenia mitigation, and metabolic health. It addresses key challenges, including the impact of protein source and chronic amino acid elevations, and validates findings through comparative analysis of clinical outcomes across different dietary patterns and populations. The review concludes by highlighting emerging research directions and the potential for targeted nutritional and pharmaceutical interventions.

The Dual Role of Amino Acids: Molecular Mechanisms in Insulin Signaling and Metabolic Regulation

Skeletal Muscle as the Primary Site of Insulin-Stimulated Glucose Disposal

Skeletal muscle is the principal site for postprandial glucose clearance, accounting for approximately 80% of insulin-mediated glucose disposal [1] [2] [3]. This whitepaper details the molecular mechanisms governing glucose uptake in skeletal muscle and examines how dietary proteins and amino acids modulate this process. We explore the signaling pathways involved, the impact of different protein interventions on insulin sensitivity, and the experimental methodologies used to investigate these relationships. The complex, dual role of amino acids—both as potential enhancers and disruptors of insulin signaling—is discussed within the context of developing targeted therapeutic and nutritional strategies for managing insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Skeletal muscle is the largest organ in the human body and the major determinant of whole-body glucose metabolism. After a meal, the rise in blood glucose triggers insulin secretion, which in turn stimulates skeletal muscle to absorb glucose from the bloodstream. The central role of skeletal muscle in this process is underscored by quantitative assessments showing it is responsible for the majority of insulin-stimulated glucose disposal [1] [3]. This immense capacity makes skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity a critical factor in systemic metabolic health; its dysfunction is a primary feature of insulin resistance and T2D.

Contemporary research into glucose homeostasis increasingly focuses on the interplay between macronutrients, revealing that dietary proteins and amino acids are potent modulators of metabolic pathways beyond their traditional role in muscle protein synthesis. This review will dissect the mechanisms of skeletal muscle glucose disposal and frame these findings within a growing body of research on the impact of dietary proteins and amino acids.

Quantitative Data on Muscle Glucose Disposal

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings related to skeletal muscle's role in glucose disposal and the effects of dietary interventions.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Data on Skeletal Muscle Glucose Disposal and Dietary Protein Effects

| Parameter | Quantitative Finding | Context / Intervention | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose Disposal | ~80% of insulin-stimulated glucose disposal | Postprandial state in humans | [1] [3] |

| Weight Loss | -8.05 kg (HPA) / -7.70 kg (HPP) | 6-month low-calorie, high-protein (35%E) diet | [4] |

| HbA1c Reduction | -0.8% | 5-week high-protein (30%E) diet vs. -0.3% with control diet | [5] |

| 24-h Glucose AUC | 40% decrease | 5-week high-protein diet vs. control diet | [5] |

| Optimal Protein Intake | 12.20-16.85 %E | U-shaped association with T2D risk; cut-off at 14.53%E | [6] |

| Leg Glucose Uptake | 45% decline | After 3 days of bed rest in young, healthy adults | [2] [3] |

Molecular Mechanisms of Insulin-Stimulated Glucose Uptake

The translocation of the glucose transporter GLUT4 to the plasma membrane is the fundamental event in insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle [7]. This process is orchestrated by a highly coordinated insulin signaling cascade and cytoskeletal remodeling.

Canonical Insulin Signaling and GLUT4 Translocation

Insulin binding to its receptor initiates a phosphorylation cascade. A critical downstream effector is the small GTPase Rac1 [7]. Upon insulin stimulation, Rac1 is activated and facilitates the rearrangement of the cortical actin network. This remodeling is essential for the translocation and docking of GLUT4 storage vesicles (GSVs) at the plasma membrane, enabling the uptake of glucose.

The diagram below illustrates the core signaling pathway from the insulin receptor to GLUT4 translocation.

Critical Research Findings on Signaling Components

- Rac1 Activation: Rac1 activation is necessary and sufficient for insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. Expression of a constitutively active Rac1 mutant can induce GLUT4 translocation and glucose uptake even in the absence of insulin [7].

- Akt2 Dependency: The activation of Rac1 in this pathway is dependent on the protein kinase Akt2, highlighting a key link between the canonical insulin signaling pathway and cytoskeletal reorganization [7].

- Molecular Link: The guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) FLJ00068 has been identified as a critical molecular link, transducing signals from Akt2 to activate Rac1 [7].

Impact of Dietary Proteins and Amino Acids on Insulin Sensitivity

The relationship between dietary protein, amino acids, and insulin resistance is complex and exhibits a duality: acute or strategic intake can be beneficial, while chronic imbalances can be detrimental.

Beneficial Effects of High-Protein Diets and Amino Acids

Table 2: Mechanisms and Evidence for Beneficial Effects of Protein/AA

| Mechanism | Experimental Evidence | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Muscle Mass Preservation | High-protein (35-45%E) diet during caloric restriction preserves fat-free mass. | Maintains glucose disposal capacity; enhances fat loss [1] [2]. |

| mTOR Activation & MPS | Leucine and Essential AA (EAA) intake acutely activates mTORC1. | Stimulates muscle protein synthesis (MPS), maintaining metabolic tissue [1] [3]. |

| Mitochondrial Biogenesis | Leucine activates SIRT1/AMPK/PGC-1α axis. | Augments mitochondrial function and fatty acid oxidation, improving insulin sensitivity [2] [3]. |

| Direct Glycemic Control | High-protein diet (30%E) vs. control (15%E) in T2D subjects. | 40% lower 24-h glucose AUC; 0.8% greater HbA1c reduction [5]. |

| Source-Independent Benefit | 6-month hypoenergetic diets with protein from 75% animal (HPA) or plant (HPP) sources. | Both HPA and HPP improved body composition and glycemic markers equally [4]. |

Detrimental Effects and the "Amino Acid Paradox"

Paradoxically, chronic elevations of certain amino acids, particularly branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), are strongly associated with insulin resistance [1] [8] [9].

- Chronic mTOR Activation: Sustained high BCAA levels lead to chronic activation of the mTOR-S6K1 pathway. This results in feedback inhibition of insulin signaling by promoting serine phosphorylation of Insulin Receptor Substrate-1 (IRS-1), which impairs PI3K activation and downstream glucose uptake [1] [9].

- Lipotoxicity: The pathogenic link between BCAAs and insulin resistance often relies on a background of nutrient overload and chronic hyperinsulinemia, which fosters lipotoxicity. This environment exacerbates the defects in insulin signaling [1].

- Context is Key: The detrimental effects are typically linked to chronic postabsorptive elevations, as seen in obesity, in contrast to the beneficial acute postprandial rises that stimulate anabolic processes [2] [3].

The following diagram summarizes the dual role of amino acids in regulating insulin sensitivity.

Key Experimental Models and Protocols

Research in this field relies on a combination of human clinical trials, advanced metabolic phenotyping, and molecular biology techniques.

Human Dietary Intervention Studies

Protocol: Long-Term, High-Protein, Low-Calorie Diet Trial [4]

- Objective: To compare the effects of plant-based versus animal-based high-protein diets on glycaemic outcomes in subjects with overweight/obesity and prediabetes or T2D.

- Design: 6-month randomized controlled trial.

- Participants: 117 adults with BMI >27.5 kg/m² and glucose metabolism disorders.

- Intervention: Two hypoenergetic diets (-30% TCV) with 35% protein. The HPA group derived 75% of protein from animal sources, while the HPP group derived 75% from plant sources.

- Key Methodologies:

- Body Composition: Assessed using Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA).

- Glycaemic Measures: Fasting glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR, HbA1c.

- Metabolic Biomarkers: Liver enzymes, lipid profiles, inflammatory biomarkers (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6), and incretins (GLP-1, GIP) measured via immunoassays.

- Outcome: Both diets similarly improved body weight, fat mass, visceral fat, and all key glycaemic parameters, indicating that the protein source was not a primary factor in the context of weight loss.

Acute Metabolic Studies

Protocol: Protein-Only vs. Carbohydrate-Only Ingestion [10]

- Objective: To compare hormonal and metabolic responses to isocaloric drinks of pure whey protein versus pure carbohydrate.

- Design: Randomized, double-blinded, balanced cross-over study.

- Participants: 14 young, healthy, trained individuals.

- Intervention: After an overnight fast, participants consumed a drink containing either 1.2 g·kg⁻¹ whey protein (PRO) or an isocaloric amount of carbohydrate (CHO).

- Key Methodologies:

- Blood Sampling: Frequent sampling over 4 hours to measure plasma glucose, amino acids, insulin, glucagon, GLP-1, and GIP.

- Urine Collection: Collected in 6 consecutive batches over 24 hours to measure nitrogen excretion.

- Outcome: PRO ingestion stimulated a significant insulin response independent of glucose, mediated by a rise in plasma AAs and GLP-1. This highlights the direct insulinotropic effect of protein.

Molecular Profiling in Human Muscle

Protocol: Skeletal Muscle Proteomics and Phosphoproteomics [8]

- Objective: To identify molecular signatures associated with insulin resistance in human skeletal muscle.

- Design: Case-control study with validation cohort.

- Participants: 77 participants (discovery cohort) and 46 (validation cohort) with and without T2D.

- Key Methodologies:

- Muscle Biopsy: Vastus lateralis biopsies taken under fasting conditions and during a hyperinsulinaemic-euglycemic clamp (the gold standard for measuring insulin sensitivity).

- Proteomic Analysis: High-resolution mass spectrometry to quantify ~3,000 proteins and 15,000 phosphorylation sites.

- Outcome: Identified that the fasting muscle proteome was associated with whole-body insulin resistance, independent of diabetic status. Key findings included disruptions in mTOR signaling and oxidative phosphorylation pathways, and identification of novel phospho-sites like AMPKγ3 S65.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Investigating Muscle Glucose Disposal

| Reagent / Material | Critical Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperinsulinaemic-Euglycemic Clamp | Gold-standard in vivo method for quantifying whole-body insulin sensitivity. | Measuring insulin-stimulated glucose disposal rates in human subjects [8]. |

| Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA) | Precisely measures body composition (fat mass, lean mass, bone mass). | Assessing changes in fat-free mass during dietary interventions [4]. |

| Mass Spectrometry (Proteomics/Phosphoproteomics) | High-throughput quantification of protein expression and phosphorylation status. | Identifying novel protein signatures and signaling disruptions in insulin-resistant muscle [8]. |

| Whey Protein Isolate | High-quality, rapidly digested protein source rich in essential amino acids and leucine. | Used in acute interventions to study the metabolic effects of protein/AA ingestion [10]. |

| Specific ELISAs / Immunoassays | Quantify plasma/serum levels of hormones (insulin, GLP-1, GIP) and biomarkers. | Measuring insulin and incretin responses to nutrient challenges [4] [10]. |

| ActiGraph Accelerometers | Objective measurement of physical activity levels in free-living individuals. | Monitoring and ensuring consistent activity levels during dietary trials [4]. |

| Validated Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQ) | Assess habitual dietary intake of macronutrients and micronutrients. | Estimating baseline protein intake and monitoring adherence in cohort studies [6]. |

Skeletal muscle's role as the primary site of insulin-stimulated glucose disposal is unequivocal. Understanding the molecular machinery that governs GLUT4 translocation, and how it is modulated by dietary components like proteins and amino acids, is fundamental to advancing metabolic science. The evidence demonstrates that high-protein diets, irrespective of animal or plant source, can be effective nutritional strategies for improving body composition and glycemic control, particularly in the context of weight loss. However, the paradoxical effects of amino acids underscore the importance of context—the metabolic background of the individual and the pattern of amino acid exposure (acute vs. chronic) are critical determinants of the outcome.

Future research should focus on:

- Personalized Nutrition: Leveraging molecular phenotyping, such as the proteomic signatures identified by Kjaergaard et al. [8], to tailor dietary protein recommendations for different metabolic subtypes.

- Mechanistic Deep Dive: Further elucidating the mechanisms by which specific amino acids and their metabolites influence mitochondrial function, redox status, and insulin signaling.

- Therapeutic Development: Exploring components of the Rac1 signaling pathway [7] or modifiers of mTOR activity as potential targets for novel insulin-sensitizing drugs.

This synthesis of physiology, nutrition, and molecular biology paves the way for more precise and effective interventions against insulin resistance and diabetes.

The mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) serves as a central regulator of cell growth and metabolism, integrating environmental cues to coordinate anabolic and catabolic processes. Among these cues, nutrient availability—particularly the presence of specific amino acids—plays a fundamental role in modulating mTORC1 activity. Leucine, a branched-chain amino acid (BCAA), has emerged as the most potent amino acid regulator of mTORC1 signaling [11] [12]. This review examines the molecular mechanisms through which leucine activates mTORC1, the downstream consequences for muscle protein synthesis, and the implications of this relationship within the broader context of dietary protein and amino acid effects on glucose homeostasis.

The significance of leucine-mediated mTORC1 activation extends beyond basic cellular physiology to applied clinical contexts. Muscle wasting conditions including sarcopenia, cachexia, and disuse atrophy represent substantial clinical challenges, and therapeutic strategies to counteract these processes often leverage leucine's anabolic properties [13]. Simultaneously, the relationship between chronic mTORC1 activation and metabolic diseases such as insulin resistance necessitates a nuanced understanding of context-dependent leucine effects [3] [14]. This article provides a comprehensive technical overview of the mechanisms, experimental methodologies, and research tools relevant to investigating leucine-induced mTORC1 activation and its functional outcomes.

Molecular Mechanisms of Leucine Sensing and mTORC1 Activation

The mTORC1 Complex: Structure and Core Functions

mTORC1 is a multi-protein complex consisting of mTOR as the catalytic subunit, regulatory-associated protein of mTOR (Raptor), mammalian LST8 homolog (mLST8), and additional regulatory components PRAS40 and DEPTOR [11]. Structurally, mTOR contains N-terminal HEAT repeats, FAT and FRB domains, a kinase domain, and a C-terminal FATC domain [11]. The complex functions as a master regulator of cell growth by promoting anabolic processes including protein, lipid, and nucleotide synthesis while suppressing catabolic processes such as autophagy [11]. mTORC1 activation stimulates mRNA translation and ribosome biogenesis through phosphorylation of key downstream effectors, notably the ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) and the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) [11].

Table 1: Core Components of mTORC1 and Their Functions

| Component | Function | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| mTOR | Catalytic kinase subunit | Phosphorylates downstream targets including S6K1 and 4E-BP1 |

| Raptor | Scaffolding protein | Substrate recognition and recruitment; defines mTORC1 identity |

| mLST8 | Stabilizing subunit | Enhances kinase activity; structural stability |

| PRAS40 | Regulatory subunit | Inhibitory component; dissociates upon activation |

| DEPTOR | Regulatory subunit | Inhibitory component; modulates complex activity |

Leucine Sensing and Intracellular Transport

As an essential amino acid, leucine must be obtained through dietary sources and transported into cells via specific amino acid transporters [15]. The L-type amino acid transporter (LAT) family, particularly LAT1 (SLC7A5) and LAT3 (SLC43A1), facilitate leucine uptake across the plasma membrane [15]. These transporters exhibit distinct tissue distribution patterns and functional characteristics, with LAT1 functioning as a heterodimeric exchanger dependent on its heavy chain subunit CD98hc (SLC3A2), while LAT3 operates as a facilitative diffuser with specificity for branched-chain amino acids [15]. Intracellular leucine accumulation initiates a signaling cascade that ultimately activates mTORC1, though the precise sensing mechanisms have only recently been elucidated.

Key Molecular Machinery in Leucine-Dependent Activation

Leucine activates mTORC1 through multiple interconnected mechanisms that converge on the Rag GTPase system. The current model indicates that leucine binding to the Sestrin2 protein releases its inhibitory interaction with GATOR2, thereby permitting activation of the Rag GTPases [16] [14]. The Rag GTPases (RagA/B and RagC/D heterodimers) function as molecular switches that, in their active GTP/GDP-bound state, recruit mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface [11] [16]. This translocation positions mTORC1 in proximity to its essential activator Rheb (Ras homolog enriched in brain), which is itself regulated by growth factor signaling through the TSC complex (TSC1/TSC2/TBC1D7) [11].

Additional regulatory proteins contribute to leucine sensing, including the folliculin-folliculin interacting protein (FLIP) complex that acts as a GAP for RagC/D, and the GATOR1 complex that functions as a GAP for RagA/B [16]. Recent structural studies have revealed that the interaction between the Rag GTPases and the Raptor component of mTORC1 is crucial for lysosomal recruitment [16]. The following diagram illustrates the core leucine sensing pathway and mTORC1 activation mechanism:

Beyond the canonical Rag GTPase pathway, alternative mechanisms contribute to leucine sensing. The class III phosphoinositide 3-kinase Vps34 has been implicated in amino acid-dependent mTORC1 activation, potentially through generation of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate [13]. Additionally, the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase kinase MAP4K3 has been identified as an amino acid sensor that regulates mTORC1 independently of the insulin signaling pathway [13]. These complementary pathways may provide robustness to nutrient sensing under varying cellular conditions and ensure appropriate mTORC1 activation in response to leucine availability.

Downstream Signaling and Physiological Effects

Translation Initiation and Protein Synthesis

Leucine-activated mTORC1 stimulates muscle protein synthesis primarily through phosphorylation of two key downstream effectors: S6K1 and 4E-BP1 [11] [12]. Phosphorylation of S6K1 on Thr389 promotes its activation and subsequent phosphorylation of multiple targets including the ribosomal protein S6, thereby enhancing the translation of mRNAs containing a 5' terminal oligopyrimidine (TOP) motif, which predominantly encode components of the translation machinery [11]. Concurrently, mTORC1-mediated phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 reduces its affinity for the mRNA cap-binding protein eIF4E, releasing eIF4E to form the eIF4F initiation complex with eIF4G and eIF4A [11] [12]. This complex is essential for cap-dependent translation initiation of numerous mRNAs, particularly those with complex secondary structures in their 5' untranslated regions.

The coordinated regulation of S6K1 and 4E-BP1 by mTORC1 enhances the cellular capacity for protein synthesis while simultaneously increasing the efficiency of translation initiation. This dual mechanism allows leucine to potently stimulate muscle protein accretion, as demonstrated in multiple human studies where leucine administration increased muscle protein synthesis rates by approximately 100% [13]. The following diagram illustrates the key downstream signaling events and functional outcomes:

Additional Metabolic Effects

Beyond its canonical role in stimulating protein synthesis, leucine-activated mTORC1 influences multiple aspects of cellular metabolism. Leucine has been demonstrated to promote mitochondrial biogenesis through activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α), enhancing oxidative capacity and fatty acid oxidation [3] [15]. This effect may occur through both mTORC1-dependent and independent pathways, potentially involving AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) [3]. Additionally, leucine contributes to lipid metabolism by inhibiting lipogenesis and promoting fatty acid oxidation, though the precise mechanisms remain incompletely characterized [15].

The metabolic effects of leucine extend to glucose homeostasis, with both beneficial and potentially detrimental consequences depending on context. Acute leucine administration can improve insulin sensitivity and enhance glucose disposal, likely through mTORC1-mediated effects on muscle metabolism [3]. However, chronic elevation of branched-chain amino acids, including leucine, has been associated with insulin resistance in obese individuals, possibly due to persistent mTORC1 activation that disrupts insulin signaling feedback loops [14]. This dual nature underscores the importance of temporal and contextual factors in determining leucine's metabolic impact.

Experimental Methodologies and Key Findings

Quantitative Data from Human and Animal Studies

Research investigating leucine-induced mTORC1 activation has employed various experimental approaches, including cell culture models, animal studies, and human clinical trials. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from selected studies:

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of Leucine on mTORC1 Signaling and Protein Synthesis

| Study Model | Leucine Intervention | Key Effects | Magnitude of Change | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human skeletal muscle (young adults) | 0.12 g leucine/kg lean mass + EAA + CHO | Phosphorylation of mTOR, S6K1, 4E-BP1; Muscle protein synthesis | ~100% increase in protein synthesis; Large increases in phosphorylation | [13] |

| Elderly humans (65-82 years) | 2.5 g leucine, 3×/day for 6 weeks | Lean body mass, Muscle strength | Significant increases vs. placebo | [15] |

| Rat skeletal muscle | 0.14 g leucine/kg body weight | Muscle protein synthesis | Near maximal increase | [13] |

| L6 myoblasts | 2 mM leucine | Phosphorylation of 4E-BP1, S6K1, S6; Protein synthesis | Increased phosphorylation; Effect abolished by rapamycin | [13] |

| Human skeletal muscle | 10 g essential amino acids (leucine-enriched) | mTOR signaling, Muscle protein synthesis | Activation at 3 hours post-ingestion | [13] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Human Skeletal Muscle Biopsy Protocol for mTOR Signaling Analysis

The assessment of mTORC1 activation in human skeletal muscle typically employs the percutaneous needle biopsy technique before and after leucine administration. The following protocol outlines key methodological considerations:

Pre-Intervention Baseline: Following an overnight fast, obtain baseline muscle biopsy from the vastus lateralis under local anesthesia using a Bergström-type needle with suction applied.

Leucine Administration: Administer a leucine-enriched essential amino acid solution typically providing approximately 0.12 g leucine per kg lean body mass, often combined with carbohydrate (30 g) to moderate insulin response [13].

Post-Intervention Sampling: Obtain subsequent muscle biopsies at predetermined timepoints (e.g., 1-3 hours post-administration) from the same leg at proximal sites separated by 2-3 cm.

Sample Processing: Immediately freeze tissue samples in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C until analysis. For phosphorylation studies, tissue may be homogenized in RIPA buffer containing phosphatase and protease inhibitors.

Western Blot Analysis: Resolve proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to PVDF membranes. Probe with phosphospecific antibodies against key mTORC1 signaling components including phospho-S6K1 (Thr389), phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr37/46), and phospho-mTOR (Ser2448), with total protein antibodies serving as loading controls [13].

Protein Synthesis Measurement: Employ stable isotope tracer methods (e.g., L-[ring-²H₅]phenylalanine) with measurement of incorporation into muscle protein via gas chromatography-mass spectrometry to quantify fractional synthetic rates [13].

Cell Culture Model for Leucine Sensing Mechanisms

In vitro approaches utilizing cell lines provide mechanistic insights into leucine sensing pathways:

Cell Culture and Starvation: Culture L6 myoblasts or other relevant cell lines in appropriate media until 70-80% confluence. Subject cells to amino acid starvation for 1-2 hours using EBSS or customized amino acid-free media.

Leucine Stimulation: Stimulate cells with physiological concentrations of leucine (0.1-2 mM) for predetermined durations (15-60 minutes).

Pharmacological Inhibition: Pre-treat cells with mTOR inhibitors (e.g., 20 nM rapamycin for 30 minutes) or other pathway-specific inhibitors to establish mechanism dependence.

Immunofluorescence and Localization Studies: Fix cells and immunostain for mTOR, LAMP2 (lysosomal marker), and Rag GTPases to assess subcellular localization using confocal microscopy.

Co-Immunoprecipitation: Assess protein-protein interactions by immunoprecipitating Raptor or other complex components and probing for associated proteins such as Rag GTPases under varying leucine conditions.

Gene Silencing Approaches: Utilize siRNA or CRISPR/Cas9 to knock down candidate sensors (e.g., Sestrin2, LAT1) and assess impact on leucine-induced mTORC1 activation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Leucine-mTORC1 Signaling

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Mechanistic Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| mTOR inhibitors | Rapamycin, Torin1 | Establish mTOR dependence; Distinguish mTORC1 vs. mTORC2 functions | Rapamycin-FKBP12 complex binds FRB domain causing steric hindrance [11] |

| Phosphospecific antibodies | p-S6K1 (Thr389), p-4E-BP1 (Thr37/46), p-mTOR (Ser2448) | Assess pathway activation in Western blot, immunohistochemistry | Readouts of mTORC1 kinase activity [13] |

| Amino acid transporters inhibitors | BCH (LAT1 inhibitor), JPH203 (LAT1-specific) | Determine leucine transport requirements | Distinguish system L transport contributions [15] |

| Stable isotopes | L-[ring-²H₅]phenylalanine, L-[1-¹³C]leucine | Quantify protein synthesis rates in vivo | Measure fractional synthetic rate via tracer incorporation [13] |

| Genetic tools | siRNA against Sestrin2, RagA/B, Raptor; CRISPR/Cas9 knockouts | Establish necessity of specific components | Molecular dissection of sensing machinery [16] |

| Metabolic assays | Seahorse extracellular flux analysis, glucose uptake assays | Assess broader metabolic consequences | Evaluate mitochondrial function, energy metabolism [3] |

Contextual Integration: Leucine Signaling and Glucose Homeostasis

The relationship between leucine-induced mTORC1 activation and glucose homeostasis represents a critical interface with significant research and therapeutic implications. Multiple studies have demonstrated that increased dietary protein intake, particularly when rich in leucine, can improve metabolic parameters during weight loss interventions. In one clinical trial comparing high-protein (45% protein) versus high-carbohydrate (20% protein) diets, the high-protein group exhibited greater improvements in insulin-stimulated glucose disposal alongside preservation of fat-free mass [17]. These findings suggest that leucine's anabolic effects on skeletal muscle—the primary site of insulin-stimulated glucose disposal—may indirectly support glucose homeostasis by maintaining metabolic tissue.

The timing and chronicity of leucine exposure appear to critically influence metabolic outcomes. Acute postprandial leucine elevations promote transient mTORC1 activation that supports muscle protein synthesis and remodeling, potentially enhancing insulin sensitivity [3]. In contrast, chronic elevations in branched-chain amino acids, as often observed in obese, insulin-resistant individuals, may promote persistent mTORC1 activation that disrupts insulin signaling through negative feedback mechanisms [14]. This paradoxical relationship underscores the importance of temporal dynamics in leucine signaling, where oscillatory activation patterns likely support metabolic health while sustained activation promotes dysfunction.

Molecular mechanisms linking leucine sensing to glucose homeostasis extend beyond muscle protein synthesis. Leucine has been demonstrated to activate PGC-1α through both mTOR-dependent and independent pathways, enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism in muscle and adipose tissue [3]. Additionally, leucine influences hepatic glucose production and whole-body energy expenditure through mechanisms that remain incompletely characterized but may involve cross-talk with AMPK signaling [3] [14]. The integration of these pathways highlights the systems-level impact of leucine signaling on metabolic regulation.

Leucine activation of mTORC1 represents a fundamental mechanism linking nutrient availability to cellular growth and metabolic regulation. The molecular machinery comprising LAT transporters, Sestrin2, GATOR complexes, Rag GTPases, and Rheb converges to position mTORC1 at the lysosomal surface where it becomes fully activated. This signaling cascade culminates in phosphorylation of downstream effectors that enhance the cellular capacity for protein synthesis through multiple complementary mechanisms. The experimental methodologies summarized herein provide robust approaches for investigating this pathway in various biological contexts.

Future research should address several outstanding questions in the field, including the potential role of leucine metabolites in mTORC1 regulation, the impact of aging and disease states on leucine sensing efficiency, and the development of therapeutic strategies to modulate this pathway for clinical benefit. Additionally, the dual nature of leucine's effects on insulin sensitivity—with acute benefits but potential chronic detrimental effects—warrants further investigation to establish optimal dosing patterns that maximize anabolic responses while supporting metabolic health. As our understanding of leucine sensing mechanisms continues to evolve, so too will opportunities to leverage this pathway for combating muscle wasting disorders while maintaining glucose homeostasis.

{Abstract} Branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs)—leucine, isoleucine, and valine—occupy a complex and paradoxical role in metabolic regulation. While acute exposure facilitates beneficial anabolic signaling and glucose homeostasis, chronic elevation is strongly associated with the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes [2] [18] [19]. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to dissect this duality, detailing the molecular mechanisms, presenting key experimental data, and providing a toolkit for researchers navigating this critical field in metabolic disease research.

{1 Introduction: The Duality of BCAAs in Metabolism} The influence of dietary proteins and amino acids on glucose homeostasis is a central theme in metabolic research. Within this context, BCAAs are unique for their tissue-specific metabolism—initial catabolism occurs primarily in skeletal muscle rather than the liver—and their potent signaling capabilities [19]. Elevated circulating BCAA levels are one of the earliest and most consistent biomarkers of obesity and future insulin resistance [20] [21]. Paradoxically, acute supplementation, particularly of leucine, is known to stimulate insulin secretion and support muscle protein synthesis [2] [19]. This document frames the BCAA paradox within the broader investigation of how dietary proteins impact metabolic health, exploring the fine line between essential physiological signaling and chronic metabolic disruption.

{2 Mechanistic Insights: From Signaling to Dysregulation} The paradoxical effects of BCAAs are mediated by distinct molecular pathways, activated in a context-dependent manner.

2.1 Acute Anabolic and Metabolic Signaling Postprandial elevations in BCAAs, especially leucine, act as critical anabolic signals. The primary mediator is the mammalian Target of Rapamycin Complex 1 (mTORC1) [2] [3]. Acute leucine-induced activation of mTORC1 in skeletal muscle promotes protein synthesis and muscle maintenance, which is crucial for systemic glucose disposal [2]. Furthermore, acute BCAA exposure can augment mitochondrial biogenesis via the SIRT1-AMPK-PGC-1α axis, enhancing oxidative metabolism and insulin sensitivity [2] [3].

2.2 Chronic Pathogenic Mechanisms Sustained high levels of BCAAs drive insulin resistance through multiple, non-exclusive mechanisms:

- Chronic mTOR Activation: Persistent mTORC1 signaling leads to the negative feedback inhibition of insulin receptor substrate (IRS) proteins, impairing the proximal insulin signaling cascade [2].

- Induction of Adipose Tissue Inflammation: Recent research highlights that BCAA accumulation in obesity promotes the polarization of adipose tissue macrophages (ATMs) towards a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype [22] [23]. This occurs via the IFNGR1/JAK1/STAT1 signaling pathway, leading to the secretion of cytokines like TNF-α, IL-1β, and MCP-1, which directly disrupt insulin action [22] [23].

- Hepatic Metabolic Reprogramming: Restricting specific BCAAs, particularly isoleucine, reprograms liver and adipose metabolism, activating the FGF21-UCP1 axis to increase energy expenditure and improve hepatic insulin sensitivity [21].

- Incomplete Catabolism and Metabolite Accumulation: Obesity-related impairment of the branched-chain keto acid dehydrogenase (BCKDH) complex leads to the accumulation of not only BCAAs but also various bioactive catabolic intermediates (e.g., BCKAs, 3-hydroxy-isobutyrate), which can further exacerbate metabolic stress [22] [23] [19].

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways that underlie the BCAA paradox:

{3 Key Experimental Findings and Data Synthesis} Research across animal models and human studies has quantified the distinct metabolic impacts of BCAAs and their restriction. The following tables summarize critical quantitative findings.

Table 1: Metabolic Effects of Acute BCAA Infusion vs. BCAA Restriction in Mouse Models

| Experimental Intervention | Key Metabolic Outcome | Observed Effect | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single BCAA Infusion (in mice) | Blood Glucose & Plasma Insulin | Acutely elevated | [20] |

| Constant BCAA Infusion (during clamp) | Whole-Body Insulin Sensitivity | Impaired | [20] |

| Single BT2 injection (BCAA-lowering drug in HFD mice) | Glucose Tolerance | Markedly improved | [20] |

| Low-Isoleucine Diet (67% reduction for 3 weeks) | Glucose Tolerance | Significantly improved | [21] |

| Low-Valine Diet (67% reduction for 3 weeks) | Glucose Tolerance | Trend toward improvement (p=0.06) | [21] |

| Low-Leucine Diet (67% reduction for 3 weeks) | Glucose Tolerance | No significant effect | [21] |

Table 2: Human and Mouse Studies on Chronic BCAA Supplementation

| Study Model | Intervention | Key Findings on Metabolism & Inflammation | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obese, Prediabetic Humans (n=12) | 20g BCAA/day for 4 weeks | No significant impairment of glucose metabolism during OGTT; mixed effects on inflammatory markers. | [24] |

| High-Fat Diet Fed Mice | High BCAA Diet | Induced obesity, insulin resistance, and pro-inflammatory M1 macrophage polarization in adipose tissue. | [22] [23] |

| High-Fat Diet Fed Mice | BCAA Supplementation | Activated IFNGR1/JAK1/STAT1 pathway in adipose tissue macrophages. | [22] [23] |

{4 Detailed Experimental Protocols} To facilitate replication and further investigation, here are detailed methodologies from key studies cited.

4.1 Acute BCAA Infusion and Metabolic Phenotyping in Mice [20]

- Animals: 3-month-old C57Bl/6J mice.

- Catheter Implantation: Jugular vein catheterization under isoflurane anesthesia for precise intravenous infusions and blood sampling.

- Acute Interventions:

- BCAA Group: A single infusion of 2.25 mmole/kg BW BCAAs (in a 2:1:1 ratio of Leu:Ile:Val) prepared in 150 mM saline.

- BT2 Group: A single intraperitoneal injection of BT2 (3,6-dichlorobenzo[b]thiophene-2-carboxylic acid; 4 mg/mL) to acutely lower circulating BCAA levels.

- Metabolic Assessments:

- Frequent Blood Sampling: Via jugular catheter to monitor acute changes in blood glucose and plasma insulin.

- Hyperinsulinemic-Euglycemic Clamp: The gold-standard method for assessing whole-body insulin sensitivity. BCAAs were constantly infused during the clamp to evaluate their direct impact on insulin-stimulated glucose disposal.

- Glucose Tolerance Test (GTT): Performed to assess glycemic control.

4.2 Investigating Adipose Tissue Macrophage Polarization [22] [23]

- Animal Model: C57BL/6J male mice divided into:

- Standard Chow (STC)

- High-Fat Diet (HFD)

- High BCAA Diet (Teklad-based diet with 150% added BCAA)

- Duration: 16 weeks.

- Tissue Collection & Analysis:

- Subcutaneous White Adipose Tissue (sWAT) was collected.

- Histology & Immunostaining: Tissues were sectioned and stained with H&E and antibodies against TNF-α, IL-1β, and MCP-1 to quantify inflammation.

- ELISA: Adipose tissue homogenates were analyzed using commercial kits to quantify TNF-α, IL-1β, and MCP-1 protein levels.

- RNA-Sequencing & Pathway Analysis: ATMs were isolated from STC and High BCAA-fed mice. Transcriptomic analysis identified the INFGR1/JAK1/STAT1 pathway. Targeted gene silencing of IFNGR1 was used for mechanistic validation in vitro.

{5 The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents} The following table compiles essential materials and tools for designing experiments in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for BCAA and Insulin Resistance Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example & Context |

|---|---|---|

| Defined Amino Acid Diets | To precisely control dietary intake of individual BCAAs and study their specific metabolic effects. | Diets with 67% reduction in all BCAAs, isoleucine, valine, or leucine, as used in [21]. |

| Pharmacological BCAA-Lowering Agent (BT2) | An inhibitor of BCKDH kinase (BDK), which promotes BCAA catabolism. Used to acutely reduce circulating BCAA levels. | 3,6-dichlorobenzo[b]thiophene-2-carboxylic acid; administered via i.p. injection [20]. |

| DREADD Systems (Chemogenetics) | For precise neuronal manipulation to study brain-periphery communication in metabolism. | AAV8-hSyn-DIO-hM3D(Gq)-mCherry injected into the mediobasal hypothalamus to activate AgRP neurons [20]. |

| Jugular Vein Catheters | Enables repeated intravenous infusions, precise compound delivery, and frequent blood sampling in rodent models. | Used for acute BCAA infusion and frequent sampling in mice [20]. |

| ELISA Kits (Cytokines) | To quantify protein levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in tissues or plasma. | Commercial kits for TNF-α, IL-1β, and MCP-1 (e.g., from R&D Systems) used on adipose tissue homogenates [23]. |

| Antibodies for Immunostaining | For spatial localization and quantification of specific proteins (e.g., inflammatory markers) in tissue sections. | Anti-TNF-α, anti-IL-1β, anti-MCP-1 antibodies (e.g., from Abcam) for immunohistochemistry in adipose tissue [23]. |

{6 Conclusion and Research Directions} The evidence unequivocally demonstrates that BCAAs are not merely passive biomarkers but active players in metabolic health, with their effects critically dependent on temporal exposure and metabolic context. The paradox is resolved by understanding that acute, postprandial signaling is essential for anabolism, while chronic elevation—often driven by an obesogenic environment and impaired catabolism—triggers inflammatory pathways and disrupts insulin action. Future research must focus on:

- Translating the distinct roles of isoleucine, valine, and leucine into targeted dietary or pharmacological interventions.

- Elucidating the precise communication mechanisms between adipose tissue inflammation, the central nervous system, and peripheral insulin sensitivity.

- Validating the IFNGR1/JAK1/STAT1 pathway as a therapeutic target in human metabolic disease.

Understanding the BCAA paradox is fundamental to advancing the broader thesis of how dietary proteins and amino acids orchestrate glucose homeostasis, offering a clear path from basic mechanism to therapeutic application.

Mitochondrial biogenesis is a critical adaptive process that ensures cellular energy homeostasis, with the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α) serving as its master regulator. This whitepaper examines the intricate regulatory network controlling PGC-1α activity, with particular emphasis on its modulation by SIRT1 deacetylation and the emerging role of amino acid metabolism. Within the context of dietary influences on glucose homeostasis, we explore how nutrient-sensing pathways converge on mitochondrial function. The document provides a technical resource for researchers, featuring synthesized quantitative data, experimental methodologies, and visual signaling pathways, to advance therapeutic strategies targeting mitochondrial dysfunction in metabolic diseases.

PGC-1α is a transcriptional coactivator identified as a central regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis and function [25]. It does not directly bind DNA but serves as a docking platform that interacts with numerous transcription factors to coordinate the expression of nuclear and mitochondrial genes encoding oxidative phosphorylation components [25] [26]. PGC-1α is highly expressed in metabolically active tissues—including liver, kidney, skeletal muscle, brain, and adipose tissue—where it upregulates respiratory gene expression in response to environmental stimuli such as fasting, exercise, and cold exposure [25]. Through its regulation of oxidative phosphorylation, fatty acid metabolism, and reactive oxygen species defense, PGC-1α represents a crucial nodal point integrating environmental signals with mitochondrial lifecycle and energy production.

Molecular Structure and Regulatory Mechanisms of PGC-1α

Structural Domains and Functional Motifs

The human PGC-1α protein consists of 798 amino acids with a molecular weight of 91 kDa and contains several functionally distinct regions [25]:

- Activation Domain: Located at the N-terminal region, contains LXXLL leucine-rich motifs that facilitate interaction with nuclear receptors.

- Inactivation Domain: Adjacent to the activation domain, regulates coactivator activity.

- Serine/Arginine-rich (RS) Domain: Involved in RNA splicing.

- RNA Recognition Motif (RRM): Typical of proteins involved in RNA processing.

The structural organization enables PGC-1α to interact with diverse transcription factors including PPARα, estrogen receptor, NRF-1, and NRF-2, thereby exerting pleiotropic effects on cellular metabolism [25]. The C-terminal functional region participates in mRNA processing, with mutations in RS and RRM motifs impairing PGC-1α's ability to interact with transcription factors and regulate gene transcription [25].

Transcriptional and Post-translational Regulation

PGC-1α is regulated at multiple levels through complex mechanisms:

Transcriptional Control: PGC-1α gene expression is upregulated by transcription factors including CREB, FoxO1, MEF2, and ATF2 in response to various stimuli [25]. Multiple promoter regions and alternative splicing generate several PGC-1α protein variants, with newly discovered isoforms (PGC-1α-b and PGC-1α-c) showing heightened responsiveness to stimulation such as exercise [25].

Post-translational Modifications: PGC-1α undergoes extensive regulation via acetylation, phosphorylation, methylation, and ubiquitination [25]. Key regulatory kinases include AMPK, MAPK, Akt, S6 kinase, and GSK3β, which modulate PGC-1α's transcriptional activity and stability in response to cellular energy status [25].

Table 1: Key Regulators of PGC-1α Activity

| Regulator | Effect on PGC-1α | Activating Stimuli | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMPK | Phosphorylation at Thr177 and Ser538 | Increased AMP/ATP ratio, Ca2+ | Enhanced transcriptional activity and stability |

| SIRT1 | Deacetylation | Increased NAD+ levels, fasting | Modulates coactivator function |

| p38 MAPK | Phosphorylation | Stress, exercise | Increased protein stability |

| AKT | Phosphorylation | Insulin signaling | Modulates activity |

| NF-κB | Represses expression and activity | Inflammation | Downregulates antioxidant genes |

The SIRT1-PGC-1α Signaling Axis

Molecular Interrelationships

SIRT1, an NAD+-dependent deacetylase, functions as a critical metabolic sensor that directly deacetylates PGC-1α, modulating its transcriptional activity [27] [28]. This deacetylation enables PGC-1α to promote mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism, particularly during nutrient deprivation [27]. The SIRT1-PGC-1α axis represents a fundamental mechanism linking cellular energy status to mitochondrial function, as SIRT1 activation increases with higher NAD+ levels during fasting or caloric restriction [26].

However, research reveals complex and sometimes contradictory aspects of this relationship. Some studies indicate that SIRT1-mediated deacetylation actually decreases PGC-1α coactivator activity and reduces mitochondrial content, suggesting context-dependent effects [28]. The metabolic outcomes of SIRT1 activation appear to depend on tissue type, physiological context, and experimental conditions.

AMPK as a Crucial Intermediate

AMPK serves as an essential intermediary in SIRT1-PGC-1α signaling. SIRT1 deacetylates LKB1, promoting its translocation to the cytoplasm where it activates AMPK [29]. Conversely, AMPK can enhance NAD+ biosynthesis, thereby activating SIRT1 [29]. This reciprocal regulation creates a feed-forward loop that amplifies mitochondrial biogenesis during energy deficit.

Research with SIRT1 activator SRT1720 demonstrates that its metabolic effects require AMPK activation, which occurs through inhibition of cAMP-degrading phosphodiesterases in a SIRT1-independent manner [29]. This finding suggests that SIRT1 activation and AMPK signaling represent parallel pathways that converge on PGC-1α to regulate mitochondrial function.

Figure 1: SIRT1-AMPK-PGC-1α Signaling Network. This diagram illustrates the complex interplay between SIRT1 and AMPK in regulating PGC-1α activity. Solid arrows indicate direct activation; dashed arrows represent indirect effects.

Amino Acids and Mitochondrial Biogenesis: Implications for Glucose Homeostasis

Nutrient Signaling Pathways

Amino acids influence mitochondrial biogenesis through multiple mechanisms that intersect with PGC-1α signaling:

mTOR Activation: Specific blends of essential amino acids, particularly those enriched in branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), activate mTOR signaling, increasing mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle and hippocampus [30]. This enhanced mitochondrial function correlates with improved physical and cognitive performance in aging models.

Nitric Oxide Modulation: Certain amino acid mixtures improve mitochondrial biogenesis by increasing endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) expression [31]. Nitric oxide functions as a key signaling molecule in mitochondrial-nuclear communication, with chronic low-grade NO stimulation promoting mitochondrial biogenesis.

Metabolic Substrate Provision: Amino acid metabolism provides critical intermediates for the TCA cycle, supporting oxidative phosphorylation [30]. Aspartate and arginine synthesis depends directly on respiratory chain activity, creating a direct link between amino acid availability and mitochondrial function.

Integration with Glucose Metabolism

The connection between amino acid metabolism, mitochondrial biogenesis, and glucose homeostasis represents a crucial interface for metabolic health. Enhanced mitochondrial capacity in insulin-sensitive tissues promotes oxidative glucose disposal and improves whole-body glucose tolerance [32]. SIRT1 activation in brown adipose tissue enhances glucose uptake and thermogenesis, contributing to improved systemic glucose homeostasis independent of weight loss [29] [32].

Table 2: Amino Acid-Mediated Effects on Mitochondrial Function

| Mechanism | Key Amino Acids | Signaling Pathways | Metabolic Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| mTOR Activation | Branched-chain amino acids (Leucine, Isoleucine, Valine) | mTORC1 signaling | Increased mitochondrial biogenesis in muscle and brain |

| Nitric Oxide Production | Arginine, Citrulline | eNOS expression | Enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis |

| TCA Cycle Anaplerosis | Glutamine, Aspartate | Metabolic intermediate supply | Supported oxidative phosphorylation |

| GCN2 Sensing | Multiple essential amino acids | eIF2α phosphorylation | Adaptation to amino acid deficiency |

Experimental Approaches and Research Methodologies

Assessing Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Function

Gene and Protein Expression Analysis:

- Real-time PCR: Quantify PGC-1α, TFAM, NRF1, and mitochondrial gene expression [33].

- Western Blotting: Detect PGC-1α protein levels and acetylation status using specific antibodies [27] [28].

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP): Validate direct binding of PGC-1α to promoter regions of mitochondrial dynamics genes (e.g., DRP1) [33].

Functional Mitochondrial Assessment:

- Seahorse XF Analyzer: Measure oxygen consumption rate (OCR) to determine basal respiration, ATP production, maximal respiratory capacity, and spare respiratory capacity [33].

- Flow Cytometry with Mitochondrial Dyes: Use MitoSOX for mitochondrial superoxide, DiOC6(3) for membrane potential, and propidium iodide for cell death assessment [33].

- ATP Production Assays: Quantify mitochondrial ATP generation using luciferase-based methods [27].

Modulating SIRT1-PGC-1α Signaling

Pharmacological Tools:

- SIRT1 Activators: SRT1720 (5-30 mg/kg in vivo, 5 μM in vitro) [29], SCIC2.1 (25 μM in vitro) [27], Resveratrol (variable effects, 1.56±0.28 μM plasma concentration in rats) [28].

- SIRT1 Inhibitors: EX-527 (5 μM in vitro) effectively blocks SIRT1 activity [27].

- AMPK Activators: AICAR and metformin indirectly influence PGC-1α activity.

Genetic Manipulations:

- Overexpression: Lentiviral or adenoviral delivery of SIRT1 or PGC-1α to enhance expression [28].

- Knockdown Approaches: siRNA/shRNA-mediated knockdown to investigate loss-of-function effects [28] [33].

- Transgenic Models: Muscle-specific SIRT1 knockout mice and AMPKα2 knockout models [29].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Investigating SIRT1-PGC-1α Signaling. This diagram outlines a comprehensive approach to studying mitochondrial biogenesis, incorporating molecular and functional assessments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating SIRT1-PGC-1α Signaling

| Reagent/Cell Line | Application | Key Features | Experimental Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| C2C12 Myotubes | In vitro muscle metabolism model | Differentiate from myoblasts to myotubes | Study exercise-mimetic effects [28] |

| HepG2 Cells | Hepatocellular carcinoma model | High metabolic activity | Investigate liver metabolism and cancer [27] |

| N27 Dopaminergic Cells | Neuronal mitochondrial function | Dopaminergic neuronal origin | Study neurotoxicity and protection [33] |

| SRT1720 | SIRT1 activator | Also inhibits PDEs and activates AMPK | 5-30 mg/kg in vivo, 5 μM in vitro [29] |

| EX-527 | SIRT1 inhibitor | Specific SIRT1 inhibition | 5 μM in vitro [27] |

| SCIC2.1 | SIRT1 activator | Promotes PGC-1α deacetylation | 25 μM in vitro [27] |

| AMPKα2 KO Mice | AMPK deficiency model | AMPKα2 isoform knockout | Determine AMPK-dependent effects [29] |

| Muscle-Specific SIRT1 KO | Tissue-specific SIRT1 deletion | Conditional knockout using Pax7-Cre | Study muscle-specific SIRT1 functions [29] |

Discussion and Research Implications

The regulatory network comprising PGC-1α, SIRT1, and AMPK represents a sophisticated system for maintaining energy homeostasis through mitochondrial biogenesis and functional adaptation. The emerging understanding of amino acid modulation of these pathways provides new insights into nutrient-sensing mechanisms that could be leveraged for therapeutic interventions.

Future research should address several critical questions: How do different amino acid profiles specifically modulate PGC-1α acetylation status? What explains the contradictory findings regarding SIRT1's effects on PGC-1α activity in different tissue contexts? How can tissue-specific modulation of these pathways be achieved for therapeutic benefit in metabolic diseases?

The integration of dietary protein and amino acid metabolism into the SIRT1-PGC-1α signaling framework offers promising avenues for developing nutritional and pharmacological approaches to improve glucose homeostasis through enhanced mitochondrial function. Particular promise lies in designing specific amino acid formulations that optimize mitochondrial biogenesis without overactivating detrimental pathways such as excessive mTOR signaling.

PGC-1α stands as the master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, integrating signals from nutrient sensors including SIRT1 and AMPK to coordinate cellular energy production with metabolic demand. The SIRT1-PGC-1α axis represents a crucial target for interventions aimed at improving mitochondrial function and glucose homeostasis. As research continues to elucidate the complex interactions between amino acid metabolism, nutrient signaling, and mitochondrial regulation, new opportunities emerge for addressing metabolic diseases through targeted activation of mitochondrial biogenesis pathways. The experimental methodologies and research tools outlined in this document provide a foundation for advancing our understanding of these critical regulatory mechanisms.

While dietary protein provides carbon skeletons that can be converted into glucose via gluconeogenesis, this process contributes minimally to circulating glucose levels in healthy individuals. This whitepaper examines the hepatic autoregulatory mechanisms that tightly control this process, drawing on stable isotope tracer studies, hormonal regulation research, and molecular pathway analyses. We synthesize findings demonstrating that only 4-10g of glucose enters circulation from 50g protein ingestion over 8 hours, despite theoretical potential for 25g glucose production. The clinical implications for diabetes management and drug development are substantial, as understanding these regulatory mechanisms may reveal novel therapeutic targets for controlling hepatic glucose production in metabolic disease.

The relationship between dietary protein and circulating glucose represents a significant paradox in metabolic physiology. On one hand, the carbon skeletons of most amino acids can be converted into glucose through gluconeogenic pathways [34]. Early 20th century investigations by Janney (1915) demonstrated that deaminated amino acids from dietary proteins could indeed produce glucose [34]. Subsequent research confirmed that 50-80g of glucose could theoretically be derived from 100g of ingested protein [34].

However, contrary to this theoretical potential, empirical observations consistently show minimal impact on blood glucose concentrations following protein ingestion. As early as 1913, Jacobson reported that ingestion of proteins did not raise blood glucose [34]. Later, MacLean (1924) found that feeding 50g of meat protein to subjects with and without mild diabetes produced no change in blood glucose, despite the theoretical production of 25g of glucose [34]. This discrepancy between theoretical potential and observed outcomes forms the core of the protein-glucose paradox that has persisted in metabolic research for over a century.

This whiteppaper examines the molecular mechanisms, regulatory pathways, and experimental evidence underlying hepatic autoregulation that resolves this paradox, with particular emphasis on implications for metabolic disease research and therapeutic development.

Quantitative Evidence: Minimal Glucose Release from Dietary Protein

Multiple controlled metabolic studies employing tracer methodologies have quantified the actual glucose appearance from dietary protein, consistently demonstrating minimal contribution to circulating glucose.

Table 1: Quantitative Studies of Glucose Appearance from Dietary Protein

| Study Population | Protein Source & Amount | Study Duration | Theoretical Glucose Potential | Actual Glucose Appearance | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal young subjects | 50g cottage cheese protein (casein) | 8 hours | ~25g | 9.7g | [34] |

| People with untreated T2D | 50g beef protein | 8 hours | ~25g | 2.0g | [34] |

| Healthy subjects | 23g egg protein | 8 hours | Not specified | 4.0g | [34] |

The striking disparity between theoretical potential and measured glucose appearance is consistent across study populations and protein sources. In the egg protein study, only 4g (8%) of the total 50g glucose entering circulation over 8 hours could be attributed to the ingested protein, despite 79% of the ingested protein being deaminated and thus making carbon skeletons available for gluconeogenesis [34].

The hepatic autoregulatory process responsible for this minimal glucose release operates independently of changes in circulating insulin or glucagon concentrations [34]. This autonomous hepatic regulation represents a crucial homeostatic mechanism that maintains glucose stability despite varying protein intake.

Molecular Mechanisms of Hepatic Autoregulation

The liver employs multiple sophisticated regulatory strategies to prevent excessive glucose release from dietary protein, involving substrate partitioning, allosteric regulation, and transcriptional control.

Substrate Partitioning and Oxidation

The fate of amino acid carbon skeletons after deamination is preferentially directed toward oxidation rather than gluconeogenesis. In the egg protein study, the majority of deaminated amino acid carbon appeared as CO₂, indicating direct oxidation as fuel rather than conversion to glucose [34]. This substrate partitioning ensures that amino acids are primarily utilized for energy production or protein synthesis rather than gluconeogenesis.

The regulatory mechanisms controlling the partitioning of food-derived amino acids between new protein synthesis, deamination, direct oxidation, and conversion to glucose remain incompletely understood but represent a critical area for future research and potential therapeutic intervention [34].

The Glucagon-Ureagenesis Axis

Glucagon plays a dual role in regulating both glucose and amino acid metabolism, creating a feedback loop known as the liver-alpha cell axis [35].

Diagram 1: Glucagon-mediated ureagenesis in amino acid metabolism

This axis functions as a complete feedback loop: amino acids stimulate glucagon secretion, which enhances hepatic amino acid clearance through ureagenesis, thereby reducing circulating amino acids and subsequent glucagon stimulation [35]. Disruption of this axis occurs in hepatic steatosis, where impaired glucagon receptor signaling and reduced expression of amino acid catabolism genes (Cps1, Slc7a2, Slc38a2) diminish ureagenic capacity [35].

Allosteric and Transcriptional Control

Hepatic glucose metabolism is regulated through both allosteric control and transcriptional mechanisms:

- Allosteric regulation: Key glycolytic and gluconeogenic enzymes are regulated by metabolic intermediates including ATP, citrate, fructose-2,6-bisphosphate, and acetyl-CoA [36]

- Transcriptional control: Transcription factors including EPAS1 (HIF2α) regulate the expression of genes involved in both glucose and lipid metabolism pathways [37]

- Hepatic zonation: Heterogeneous distribution of metabolic enzymes across liver lobules creates specialized compartments for glycolytic and gluconeogenic processes

The transcription factor EPAS1 plays a particularly important role as a master regulator that coordinates glucose and lipid metabolic pathways in response to oxygen availability [37].

Key Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Research elucidating hepatic autoregulation has employed sophisticated experimental designs and tracer methodologies.

Stable Isotope Tracer Protocols

The definitive studies quantifying glucose appearance from protein utilized stable isotope tracers with detailed protocols:

Diagram 2: Multitracer experimental workflow for protein metabolism

This sophisticated approach allows simultaneous tracking of both the amino moiety and carbon skeletons of dietary amino acids, providing comprehensive data on their metabolic fates [34]. The multitracer technology enables precise quantification of glucose production from all sources and attribution of specific portions to dietary protein.

Glucagon Signaling Manipulation Studies

Research on the liver-alpha cell axis has employed multiple interventional approaches:

Table 2: Experimental Approaches to Study Glucagon-Amino Acid Metabolism

| Experimental Approach | Model System | Key Findings | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucagon receptor antagonist (GRA) | Mice | Reduced amino acid clearance and urea formation | Confirms glucagon dependence of amino acid catabolism |

| Diphtheria toxin α-cell ablation | Transgenic mice | Impaired ureagenesis restored by glucagon administration | Demonstrates necessity of α-cells for amino acid homeostasis |

| Primary hepatocyte studies | Human and mouse hepatocytes | Glucagon increases urea formation within minutes | Reveals direct hepatic action mechanism |

| Transcriptomic analysis | Liver tissue from GRA-treated mice | Downregulation of Cps1, Slc7a2, Slc38a2 | Identifies key regulated genes in amino acid metabolism |

These complementary approaches establish both necessity (through loss-of-function experiments) and sufficiency (through agonist administration) of glucagon signaling for appropriate amino acid clearance and ureagenesis.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hepatic Amino Acid Metabolism Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Function in Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stable isotope tracers | ¹³C, ¹⁵N-labeled amino acids; ²H-glucose | Glucose flux studies; Amino acid oxidation measures | Metabolic pathway tracing; Flux quantification |

| Hormone modulators | Glucagon receptor antagonists; Recombinant glucagon | Signal transduction studies; Pathway necessity/sufficiency tests | Specific pathway manipulation; Receptor function analysis |

| Animal models | Glucagon receptor KO; α-cell ablation models; "Falconized" EPAS1 mice | In vivo physiology studies; Genetic pathway analysis | Whole organism physiology; Genetic mechanism studies |

| Protein sources | Intrinsically labeled egg protein; Casein; Beef protein | Substrate-specific metabolism studies | Controlled dietary protein delivery |

| Analytical platforms | UPLC-MS/MS; GC-MS; Metabolic cages | Metabolite quantification; Substrate oxidation measures | Precise metabolite measurement; Whole-body energy substrate use |

This toolkit enables comprehensive investigation of hepatic amino acid metabolism from molecular mechanisms to whole-body physiology.

Implications for Metabolic Disease and Therapeutic Development

Understanding hepatic autoregulation of glucose production from protein has significant implications for metabolic disease management and drug development.

Hepatic Steatosis and Metabolic Dysregulation

NAFLD and hepatic steatosis impair glucagon-dependent enhancement of amino acid catabolism [35]. Patients with NAFLD exhibit hyperglucagonemia and increased levels of glucagonotropic amino acids, particularly alanine [35]. The disruption of the liver-alpha cell axis in hepatic steatosis creates a pathological cycle: impaired hepatic amino acid clearance leads to elevated circulating amino acids, which stimulates glucagon secretion, but the liver cannot respond appropriately due to insulin resistance and steatosis [35] [38].

This pathophysiology may contribute to the progression from NAFLD to type 2 diabetes, as chronic hyperaminoacidemia and hyperglucagonemia can promote metabolic dysfunction. Diet-induced reduction in HOMA-IR (a marker of hepatic steatosis) reduces both glucagon and alanine levels, highlighting the potential for therapeutic intervention [35].

Protein-Sparing Therapies and Diabetes Management

The understanding that dietary protein contributes minimally to circulating glucose supports current dietary approaches for diabetes management that emphasize adequate protein intake without significant concern for direct glycemic impact. However, the impaired amino acid clearance in hepatic steatosis suggests that hepatic autoregulatory capacity may be compromised in metabolic disease.

Emerging therapeutic approaches targeting the glucagon signaling pathway, including glucagon receptor antagonists and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, may exert part of their beneficial effects through modulation of amino acid metabolism and restoration of hepatic autoregulatory function [35] [38].

Hepatic autoregulation ensures that dietary protein contributes minimally to circulating glucose through integrated mechanisms including substrate partitioning, glucagon-mediated ureagenesis, and allosteric control of metabolic enzymes. The resolution of the protein-glucose paradox represents a significant advancement in our understanding of metabolic integration.

Future research should focus on:

- Elucidating the precise signals and mechanisms that partition amino acid carbon skeletons between oxidation, gluconeogenesis, and other metabolic fates

- Developing targeted therapies that enhance hepatic autoregulatory capacity in metabolic disease

- Investigating the role of hepatic zonation in compartmentalizing amino acid metabolism

- Exploring the potential of dietary protein manipulation to modulate hepatic autoregulation for therapeutic benefit

These research directions promise to yield novel insights into liver physiology and new therapeutic approaches for metabolic diseases characterized by dysregulated hepatic glucose production.

Applied Nutritional Strategies: High-Protein Diets and Amino Acid Supplementation in Metabolic Health

Hypocaloric High-Protein Diets for Weight Loss and Insulin Sensitivity Improvement

Hypocaloric high-protein diets represent a significant evolution in nutritional science, offering a dual-targeted approach for managing obesity and metabolic syndrome. Defined as diets providing >30% of total energy from protein or >1.2 g/kg/day while maintaining a caloric deficit, these diets have demonstrated efficacy not only for weight reduction but also for fundamental improvements in metabolic regulation [39] [40]. The therapeutic potential of hypocaloric high-protein diets extends beyond simple weight management to address core pathophysiological mechanisms in insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The scientific rationale for high-protein diets is anchored in the unique metabolic properties of dietary proteins and their constituent amino acids. Branched-chain amino acids, particularly leucine, function as critical nutrient signaling molecules that influence glucose homeostasis through both central and peripheral mechanisms [40]. This review synthesizes current evidence from clinical trials, mechanistic studies, and population research to provide a comprehensive technical assessment of hypocaloric high-protein diet implementation, outcomes, and underlying biological pathways for research and drug development applications.

Quantitative Clinical Outcomes of Hypocaloric High-Protein Diets

Body Composition and Metabolic Changes

Table 1: Body Composition Changes Following Hypocaloric High-Protein vs. Conventional Diets

| Parameter | High-Protein Diet | Conventional Diet | P-value | Study Duration | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight Loss (kg) | -8.9 ± 4.6 kg | -10.0 ± 9.4 kg | >0.05 | 3 months | [41] |

| Fat-Free Mass Preservation | -1.5 ± 1.6 kg | -4.4 ± 4.2 kg | <0.01 | 3 months | [41] |

| Fat-Free Mass Index | -0.7 ± 1.1 kg/m² | -2.1 ± 1.9 kg/m² | <0.01 | 3 months | [41] |

| Body Fat Percentage | -5.3 ± 3.3% | -3.2 ± 4.5% | <0.05 | 3 months | [41] |

| Fat Mass Reduction | -7.53 ± 1.44 kg | -6.96 ± 1.36 kg | Not significant | 10 weeks | [17] |

Table 2: Metabolic Parameter Changes in Hypocaloric High-Protein Diet Interventions

| Metabolic Parameter | High-Protein Diet Effect | Comparison Condition | Study Population | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose Disposal | Significant increase | Significant decrease | Obese women | [42] |

| Glucose Oxidation | Significant increase | Significant decrease | Obese women | [42] |

| Postprandial Insulin Response | 75 ± 18 pmol/L | 207 ± 21 pmol/L | Adult women with overweight | [17] |

| Fasting Blood Glucose | Stabilized | Reduced | Adult women with overweight | [17] |

| HbA1c Reduction | Significant improvement | Moderate improvement | T2DM patients | [39] |

| 3-Methylhistidine Excretion | Reduced by 48% | Unchanged | Obese women | [42] |

Clinical evidence consistently demonstrates that while weight loss outcomes between hypocaloric high-protein and conventional diets may be similar, high-protein diets confer superior body composition outcomes by preferentially preserving metabolically active fat-free mass [41]. This preservation is critically important for maintaining resting energy expenditure during weight loss and has long-term implications for weight maintenance. The reduction in 3-methylhistidine excretion, a marker of muscle protein breakdown, provides biochemical evidence for the protein-sparing effects of high-protein diets during caloric restriction [42].

Beyond body composition, hypocaloric high-protein diets induce favorable changes in glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity. Research indicates significant improvements in glucose disposal and oxidation rates under hyperinsulinemic clamp conditions, suggesting enhanced tissue-level insulin sensitivity [42]. The substantial reduction in postprandial insulin response observed in high-protein diets indicates improved pancreatic β-cell function and reduced insulin demand, which may have long-term benefits for preserving pancreatic function in individuals with insulin resistance [17].

Mechanisms of Action: Protein and Amino Acid Signaling in Glucose Homeostasis

Central and Peripheral Signaling Pathways

The metabolic benefits of hypocaloric high-protein diets are mediated through multiple interconnected biological pathways. Understanding these mechanisms provides insights for developing targeted nutritional interventions and pharmacological approaches.

Diagram 1: Integrated signaling pathways of high-protein diets and amino acids in glucose homeostasis

The mechanisms by which hypocaloric high-protein diets improve insulin sensitivity involve complex nutrient-sensing pathways across multiple tissues. As illustrated in Diagram 1, branched-chain amino acids, particularly leucine, serve as critical signaling molecules that access the medio-basal hypothalamus through fenestrated capillaries in the arcuate nucleus [40]. Within hypothalamic neurons, leucine metabolism generates oleoyl-CoA, which activates ATP-sensitive potassium channels, initiating vagal signals to the liver that suppress hepatic glucose production through inhibition of gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis [40].

Concurrently, high-protein diets influence incretin secretion and pancreatic function. Protein and amino acid ingestion stimulates release of glucagon-like peptide-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide from intestinal L-cells, enhancing glucose-dependent insulin secretion while suppressing glucagon release [40]. This entero-endocrine axis activation contributes to the improved postprandial glycemic control observed with high-protein diets without excessive insulin secretion.

At the intestinal level, protein hydrolysates and bioactive peptides directly modulate glucose absorption capacity. In vitro and ex vivo studies demonstrate that digested proteins from various sources reduce glucose transport across intestinal epithelium by downregulating GLUT2 transporter expression [43]. This mechanism represents a direct interface between dietary protein and carbohydrate absorption, potentially contributing to the flattened glycemic curves observed with high-protein meals.

The BCAA Paradox in Insulin Resistance

The relationship between branched-chain amino acids and insulin sensitivity presents a complex paradox that requires careful consideration in research and clinical application. While acute administration of BCAAs demonstrates insulin-sensitizing effects through the mechanisms described above, chronically elevated circulating BCAA levels are strongly associated with insulin resistance and increased type 2 diabetes risk in observational studies [44].

This apparent contradiction may be explained by differences in temporal exposure and metabolic context. Chronic elevation of BCAAs, often associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome, may reflect impaired BCAA catabolism rather than solely increased dietary intake [44]. Dysfunctional BCAA catabolism in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle leads to accumulation of metabolic intermediates that activate mTOR-S6K1 signaling, promoting serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 and subsequent insulin receptor substrate degradation [45]. This negative feedback loop represents a fundamental mechanism through which chronic BCAA elevation induces insulin resistance.

The source of dietary protein significantly influences this paradoxical relationship. Plant-based proteins, particularly when consumed with high fiber content, demonstrate attenuated association with diabetes risk compared to animal proteins [46] [6]. This protective effect may be mediated through modified digestion kinetics, differential amino acid composition, or concomitant phytochemical intake that modulates BCAA metabolism.

Experimental Models and Research Methodologies

Key Research Protocols

Table 3: Standardized Experimental Protocols for High-Protein Diet Research

| Methodology | Protocol Specifications | Key Measurements | Applications | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euglycemic Hyperinsulinemic Clamp | 25 mU/kg/h insulin for 150 min + indirect calorimetry | Glucose disposal rate, glucose oxidation, lipid oxidation | Gold standard for insulin sensitivity assessment | [42] |

| INFOGEST Gastrointestinal Digestion | 2g protein in SSF (pH 7, 5 min) → SGF + pepsin (pH 3, 2h) → SIF + pancreatin (pH 7, 2h) | Bioactive peptide generation, amino acid composition | Simulation of protein digestion and metabolite release | [43] |

| Caco-2/TC7 Cell Glucose Uptake | 14C-AMG uptake after 1h pre-incubation with digested proteins (5 mg/ml) | Radioactive glucose analog transport, GLUT2/SGLT1 expression | Intestinal glucose absorption mechanisms | [43] |

| Ex Vivo Jejunal Sac Transport | 1cm rat jejunal sacs with 3H-D-[1-14C] glucose + digested proteins (31.25 mg/ml) | Serosal to mucosal glucose ratio | Validation of intestinal glucose transport findings | [43] |