Comparative Analysis of Predictive Interstitial Glucose Classification Models: From Traditional ML to Advanced Deep Learning

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of predictive models for classifying interstitial glucose levels, a critical task for modern diabetes management.

Comparative Analysis of Predictive Interstitial Glucose Classification Models: From Traditional ML to Advanced Deep Learning

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of predictive models for classifying interstitial glucose levels, a critical task for modern diabetes management. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the evolution from traditional statistical methods to sophisticated machine learning and deep learning architectures. The review systematically covers the foundational principles of glucose classification, details the implementation and application of diverse algorithmic methodologies, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, and presents a rigorous validation framework for model performance. By synthesizing recent research, this analysis offers valuable insights for developing robust, accurate, and clinically reliable tools to predict hypoglycemia, euglycemia, and hyperglycemia, ultimately supporting advancements in personalized medicine and therapeutic development.

The Fundamentals of Interstitial Glucose Prediction and Clinical Imperatives

The precise classification of interstitial glucose levels into hypoglycemia, euglycemia, and hyperglycemia represents a fundamental component in modern diabetes management and predictive model research. These clinically defined thresholds serve as the critical endpoints for developing machine learning algorithms aimed at forecasting glycemic excursions, enabling proactive interventions for individuals with diabetes. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) Standards of Care establish specific glycemic targets that have been widely adopted in both clinical practice and research settings, providing a standardized framework for evaluating glycemic status [1]. Within the research domain, these classifications form the essential basis for training and testing predictive models that analyze continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) data to forecast future glucose levels, thereby facilitating personalized treatment approaches and reducing the risk of acute complications [2] [3].

The emergence of advanced analytical approaches, collectively termed "CGM Data Analysis 2.0," which encompasses functional data analysis and artificial intelligence (AI), has further emphasized the importance of precise glucose classification [3]. These methodologies move beyond traditional summary statistics to model entire glucose trajectories as dynamic processes, offering more nuanced insights into glycemic patterns and variability. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the established clinical thresholds for glucose classification and examines their application within comparative studies of predictive interstitial glucose classification models, with particular focus on the experimental protocols and performance metrics relevant to researchers and drug development professionals.

Established Clinical Thresholds for Glucose Classification

Standard Glycemic Categories and Definitions

International consensus guidelines, primarily from the ADA and the Advanced Technologies & Treatments for Diabetes (ATTD) congress, have established standardized thresholds for classifying interstitial glucose levels. These classifications are universally employed in clinical practice and research methodologies [1] [4].

Table 1: Standard Clinical Thresholds for Glucose Classification

| Glucose Class | Threshold Range (mg/dL) | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Hypoglycemia | < 70 | Level 1 clinically significant hypoglycemia [1] [4] |

| < 54 | Level 2 hypoglycemia [5] | |

| Euglycemia | 70 - 180 | Target glucose range [2] [1] [6] |

| Hyperglycemia | > 180 | Level 1 hyperglycemia [2] [1] [6] |

| > 250 | Level 2 hyperglycemia [5] [4] |

For healthy individuals without diabetes, studies using continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) have shown that glucose levels typically remain between 70-140 mg/dL for over 90% of the day, with mean 24-hour glucose levels approximately 99-105 mg/dL [7]. This highlights the more stringent natural glycemic regulation compared to the broader targets used in diabetes management.

Key Metrics for Glycemic Assessment

Beyond threshold classification, consensus guidelines recommend specific metrics for a comprehensive assessment of glycemic status, particularly using CGM data. Time in Range (TIR), Time Below Range (TBR), and Time Above Range (TAR) provide a more dynamic view of glycemic control [1]. For patients with diabetes and concurrent renal disease, the international consensus recommends specific targets, including ≤1% TBR (<70 mg/dL), ≤10% TAR level 2 (>250 mg/dL), and ≥50% TIR (70–180 mg/dL) [4].

Comparative Analysis of Predictive Glucose Classification Models

Performance Comparison of Predictive Models

Research directly compares the efficacy of various machine learning models in predicting future glucose classifications. These studies typically use the standard clinical thresholds to define the prediction classes and evaluate performance using metrics such as precision, recall, and accuracy over different prediction horizons (PH).

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Glucose Classification Models

| Predictive Model | Prediction Horizon | Hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL) Recall | Euglycemia (70-180 mg/dL) Recall | Hyperglycemia (>180 mg/dL) Recall | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression [2] [6] | 15 minutes | 98% | 91% | 96% | Superior short-term prediction, particularly for hypoglycemia |

| LSTM [2] [6] | 1 hour | 87% | Not Specified | 85% | Best for longer-term prediction of hypo-/hyperglycemia |

| BiLSTM [8] | 5 minutes | RMSE: 13.42 mg/dL | MAPE: 0.12 | Clarke Error Grid D: 3.01% | High accuracy for very short-term prediction |

| LightGBM [9] | 15 minutes | RMSE: 18.49 mg/dL | MAPE: 15.58% | Non-invasive feasibility | Effective with non-invasive wearable data |

| Logistic Regression (Hemodialysis) [4] | 24 hours | F1: 0.48 (TabPFN) | Not Applicable | F1: 0.85 | Best for hyperglycemia prediction in complex comorbidities |

| ARIMA [2] [6] | 15 min & 1 hour | Underperformed other models | Underperformed other models | Underperformed other models | Serves as a baseline model |

Emerging Approaches: Non-Invasive Glucose Classification

A significant advancement in the field involves predicting glucose levels and their classifications using non-invasive wearable sensors, eliminating the need for invasive CGM. One study utilized an ensemble feature selection-based Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM) algorithm with data from non-invasive sensors measuring skin temperature (STEMP), blood volume pulse (BVP), heart rate (HR), electrodermal activity (EDA), and body temperature (BTEMP) [9]. This approach achieved a root mean squared error (RMSE) of 18.49 ± 0.1 mg/dL and demonstrated the feasibility of accurate, non-invasive glucose monitoring, paving the way for more accessible personalized dietary interventions [9].

Experimental Protocols and Research Methodologies

Data Sourcing and Preprocessing

Robust experimental protocols are fundamental to reliable model development. Research in this field typically utilizes two primary data sources: clinical cohort studies and in-silico simulations.

Clinical cohort data often comes from tightly controlled studies. For example, one analysis used data from the "COVAC-DM" study where participants with type 1 diabetes used CGM devices, with additional data on insulin dosing and carbohydrate intake [2]. To supplement real-world data, researchers often employ simulators like the CGM Simulator (e.g., Simglucose v0.2.1), which implements the UVA/Padova T1D Simulator to generate data for virtual patients across different age groups over multiple days, incorporating randomized meal and snack schedules [2].

A critical preprocessing step involves addressing the inherent sensor delay of approximately 10 minutes between interstitial glucose measurements and actual plasma glucose readings [2] [6]. Data is typically brought to a standard time frequency (e.g., 15-minute intervals), and gaps are addressed. For non-invasive approaches, feature engineering is crucial, deriving inputs like rate of change, variability indices, and moving averages from raw sensor data [2] [9].

Model Training and Evaluation Framework

The standard methodology for developing classification models follows a structured pipeline:

- Segmentation: The continuous CGM time series is divided into segments. A common approach uses a 24-hour feature segment preceding a dialysis session to predict glycemic outcomes over the subsequent 24-hour prediction segment [4].

- Feature Engineering: Features are extracted from the raw data. These can include CGM-derived metrics (mean glucose, variability indices), baseline patient characteristics (HbA1c, insulin use), and for non-invasive models, data from wearables (heart rate, skin temperature) [9] [4].

- Model Training and Validation: Models are trained and validated using techniques that prevent overfitting and ensure generalizability. Leave-one-participant-out cross-validation (LOPOCV) is a preferred method, as it trains the model on all participants except one, which is used for testing, iterating until each participant has been the test subject [9]. This accounts for individual variability.

- Performance Assessment: Models are evaluated based on their ability to correctly classify glucose levels. Standard metrics include:

- Recall (Sensitivity): The proportion of actual events (e.g., hypoglycemia) that were correctly identified. This is critical for safety.

- Precision: The proportion of predicted events that were correct.

- F1-Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall.

- ROC-AUC: The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, measuring overall classification performance.

- Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE): For regression-based prediction before classification.

- Clarke Error Grid Analysis (CEGA): Plots clinical accuracy of predictions, with zones A and B being clinically acceptable [9].

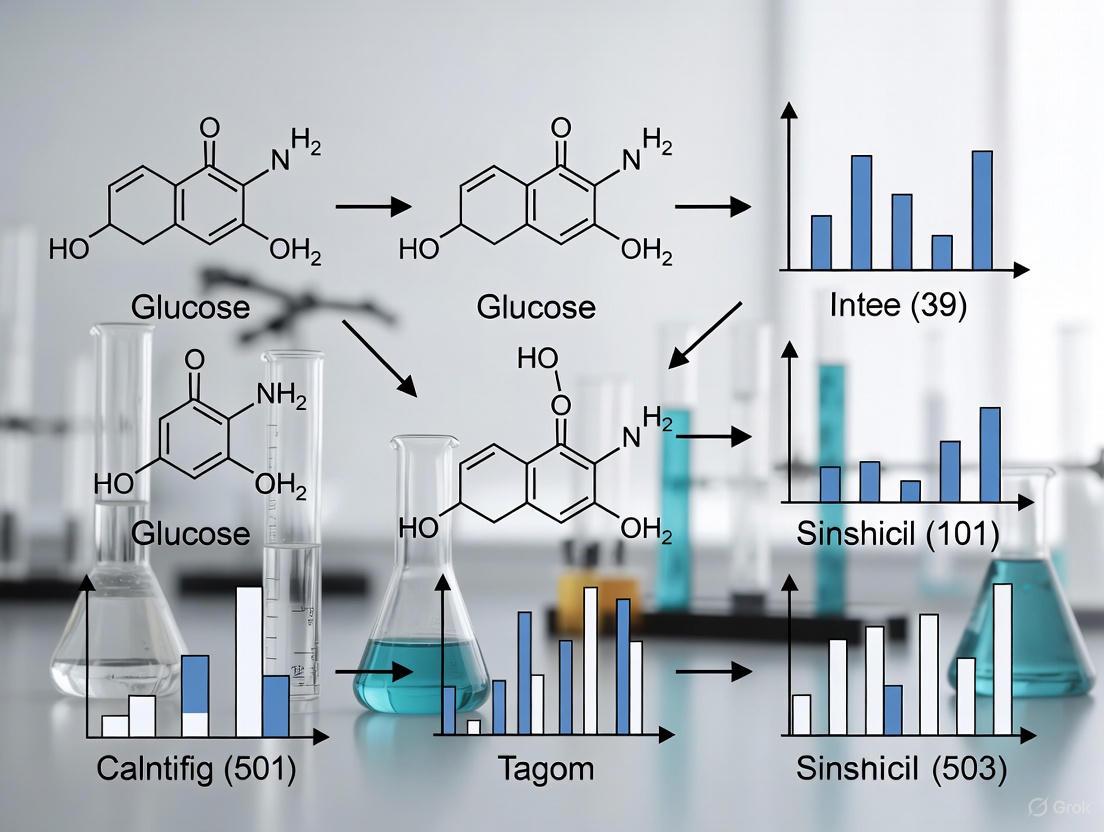

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for the experimental protocol used in comparative model studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Glucose Classification Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Example | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| CGM Platforms | Dexcom G6 [5] [4] | Provides ground-truth interstitial glucose measurements for model training and validation. |

| Non-Invasive Wearables | Empatica E4 [9] [5], Zephyr Bioharness [5] | Captures multimodal physiological data (PPG, EDA, ECG, accelerometry) for non-invasive prediction models. |

| In-Silico Simulators | Simglucose (UVA/Padova T1D Simulator) [2] | Generates large-scale, synthetic CGM and patient data for initial algorithm testing and development. |

| Programming Environments | Python [2] | Provides the ecosystem for implementing machine learning models (e.g., scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch). |

| Public Datasets | PhysioCGM Dataset [5], OhioT1DM Dataset [5] | Offers curated, multimodal physiological data with CGM for training and benchmarking models. |

| Analysis Software | Clarke Error Grid Analysis [9] | Standard method for evaluating the clinical accuracy of glucose predictions. |

The definition of glucose classes using standardized clinical thresholds is the cornerstone of developing and evaluating predictive models for interstitial glucose. Comparative analyses reveal that model performance is highly dependent on the prediction horizon, with simpler models like logistic regression excelling at short-term forecasts (15 minutes) and more complex models like LSTM networks achieving superior performance for longer-term predictions (1 hour). The field is rapidly evolving with the emergence of non-invasive monitoring using wearable sensors and advanced AI/ML techniques, collectively known as CGM Data Analysis 2.0. Future research directions will likely focus on hybrid or ensemble models that combine the strengths of multiple algorithms, the integration of non-invasive multimodal data, and the application of these models in specific, complex patient populations, such as those undergoing hemodialysis, to enhance the accuracy, reliability, and clinical applicability of glucose prediction systems.

The Role of Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) in Data Acquisition

Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) systems have revolutionized diabetes management by enabling the real-time acquisition of interstitial glucose concentrations, providing a rich data stream for predictive analytics and personalized treatment strategies [10]. Unlike traditional capillary blood glucose measurements that offer isolated snapshots, CGM devices generate dense time-series data, typically acquiring 288 measurements per day at 5-minute intervals [11]. This continuous data acquisition forms the foundation for advanced analytical approaches, including Functional Data Analysis (FDA) and artificial intelligence (AI) models, which transform raw sensor readings into clinically actionable insights [3]. The evolution from retrospective analysis to real-time predictive modeling represents a paradigm shift in how glucose data is utilized for therapeutic decision-making, particularly in the context of comparative analysis of predictive interstitial glucose classification models research.

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the data acquisition capabilities of different CGM systems is crucial for designing robust clinical trials and developing accurate predictive models. The quality, frequency, and reliability of acquired data directly impact the performance of classification algorithms aimed at predicting hypoglycemia, euglycemia, and hyperglycemia states [2]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of CGM technologies and methodologies, focusing on their role in acquiring high-quality data for predictive model development.

CGM Technologies for Data Acquisition

Modern CGM systems employ diverse technological approaches to acquire interstitial glucose data, each with distinct implications for research applications. The leading systems available in 2025 include real-time CGMs (rtCGM) that continuously transmit data and intermittently scanned CGMs (isCGM) that require user activation for data retrieval [11]. These systems vary significantly in their form factors, wear duration, and data acquisition characteristics, which must be carefully considered when selecting platforms for research studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Leading CGM Systems for Data Acquisition (2025)

| CGM System | Wear Duration | Accuracy (MARD) | Warm-up Time | Data Points per Day | Key Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dexcom G7 | 15 days | 8.2% (adults) [12] | 30 minutes [12] | 288 | High-accuracy predictive modeling; pediatric studies |

| Abbott FreeStyle Libre 3 | 14 days | 8.9% (2025 study) [12] | 1 hour (est.) | 288 | Large-scale observational studies; cost-effective research |

| Medtronic Guardian 4 | 7 days | 9-10% [12] | Varies | 288 | Insulin pump integration studies; closed-loop systems |

| Eversense 365 | 365 days | 8.8% [12] | Single annual warm-up [12] | 288 | Long-term glycemic variability studies; adherence research |

| Dexcom Stelo | 15 days | ~8-9% [12] | 30 minutes [12] | 288 | Type 2 diabetes non-insulin studies; wellness research |

The Mean Absolute Relative Difference (MARD) represents the standard metric for assessing CGM accuracy, with lower values indicating higher accuracy relative to reference blood glucose measurements [12]. MARD values below 10% are generally considered excellent for clinical and research applications, with most contemporary systems now achieving this benchmark. The Eversense 365 system is particularly noteworthy for research applications requiring long-term data acquisition without frequent sensor replacements, as its implantable nature and 365-day wear time enable unprecedented longitudinal studies of glycemic patterns [12].

Recent innovations are expanding the boundaries of CGM data acquisition. Biolinq's Shine wearable biosensor received FDA clearance in 2025 as a needle-free, non-invasive CGM that utilizes a microsensor array manufactured with semiconductor technology, registering up to 20 times more shallow than conventional CGM needles [13]. Glucotrack is advancing a 3-year monitor that measures glucose directly from blood rather than interstitial fluid, potentially eliminating the lag time associated with current CGM systems [13]. These emerging technologies promise to address current limitations in CGM data acquisition, including sensor lag and measurement disparities between interstitial fluid and blood glucose.

Comparative Analysis of Predictive Model Performance

The primary value of CGM-acquired data lies in its application for predicting future glucose states, enabling proactive interventions for diabetes management. Research has evaluated numerous predictive modeling approaches, each with distinct strengths and limitations for classifying interstitial glucose levels. The performance of these models varies significantly based on prediction horizon and the specific glycemic state being predicted.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Predictive Glucose Classification Models

| Model Type | 15-Minute Prediction Recall | 60-Minute Prediction Recall | Optimal Prediction Horizon | Key Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | Hyper: 96%, Norm: 91%, Hypo: 98% [2] | Lower performance vs. LSTM [2] | 15-30 minutes | Short-term hypoglycemia预警 |

| LSTM Networks | Strong performance, slightly lower than logistic regression [2] | Hyper: 85%, Hypo: 87% [2] | 30-60 minutes | Longer-term trend prediction; pattern recognition |

| Multimodal Deep Learning (CNN-BiLSTM with Attention) | MAPE: 6-24 mg/dL (varies by sensor) [14] | MAPE: 12-26 mg/dL (varies by sensor) [14] | 15-60 minutes | Personalized prediction integrating physiological context |

| ARIMA | Underperformed other models [2] | Underperformed other models [2] | Limited utility | Baseline comparison; simple trend analysis |

The comparative analysis reveals that model performance is highly dependent on prediction horizon. Logistic regression excels at short-term predictions (15 minutes), achieving remarkable recall rates of 98% for hypoglycemia and 96% for hyperglycemia [2]. In contrast, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks demonstrate superior performance for longer prediction horizons (60 minutes), making them better suited for anticipating glycemic trends that enable more proactive interventions [2].

Recent advances in multimodal deep learning architectures have demonstrated particularly promising results for personalized glucose prediction. One 2025 study achieved up to 96.7% prediction accuracy by integrating CGM data with baseline physiological information using a stacked Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and Bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM) with attention mechanisms [14]. This approach significantly outperformed unimodal models at 30-minute and 60-minute prediction horizons, highlighting the value of incorporating contextual physiological data alongside CGM time-series data [14].

Experimental Protocols for Predictive Model Development

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Robust experimental protocols are essential for developing accurate predictive models based on CGM data. The foundational step involves standardized data acquisition using CGM systems with appropriate accuracy characteristics (typically MARD <10%). Research-grade data collection should include:

- CGM Device Selection: Choose devices with validated accuracy metrics appropriate for the research population. For mixed-meal studies or rapid glycemic excursion research, prioritize devices with minimal sensor lag [2].

- Sampling Protocol: CGM values are typically sampled every 5 minutes, generating 288 measurements daily [11]. For predictive modeling, data is often restructured using a moving window approach (e.g., 30-minute samples with 5-minute moving windows) [14].

- Data Quality Control: Implement procedures to address signal loss, sensor noise, and compression hypoglycemia artifacts [2]. This may include Kalman smoothing techniques to correct inaccurate CGM readings [2].

- Stationarity Validation: Confirm stationarity of CGM time series using statistical tests like the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test before model development [14].

Model Training and Validation

Following data acquisition and preprocessing, a structured approach to model training and validation ensures reproducible results:

- Data Partitioning: Implement rigorous cross-validation strategies, typically using patient-wise splits rather than temporal splits to prevent data leakage and ensure generalizability [14].

- Feature Engineering: For unimodal approaches using only CGM data, derive features including rate of change metrics, variability indices, rolling averages, and seasonal decomposition components [2]. For multimodal approaches, integrate baseline physiological parameters such as demographics, comorbidities, and medication usage [14].

- Evaluation Metrics: Utilize comprehensive evaluation metrics including precision, recall, F1-score, accuracy, and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) for each glucose class (hypoglycemia, euglycemia, hyperglycemia) [2]. Implement clinical accuracy assessment using Parkes Error Grid analysis [14].

- Statistical Significance Testing: Perform appropriate statistical tests (e.g., t-tests) to validate performance differences between model architectures [14].

CGM Predictive Modeling Workflow

Advanced Analytical Approaches

Evolution from Traditional Statistics to Advanced Analytics

The analysis of CGM-acquired data has evolved significantly from traditional summary statistics to sophisticated analytical approaches collectively termed "CGM Data Analysis 2.0" [3]. This evolution reflects the growing recognition that traditional metrics oversimplify complex glucose dynamics:

- CGM Data Analysis 1.0: Traditional summary statistics include percentage time in glycemic ranges, glucose management indicator (GMI), and coefficient of variation [3]. While easily interpretable, these metrics lack granularity in capturing complex temporal patterns and are prone to distortion from missing data [3].

- CGM Data Analysis 2.0: Advanced approaches include Functional Data Analysis (FDA), machine learning (ML), and artificial intelligence (AI) [3]. These methods leverage the entire CGM time series, identifying nuanced phenotypes and enabling personalized decision-making frameworks [3].

Table 3: Comparison of CGM Data Analysis Approaches

| Analytical Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Summary Statistics | Aggregated metrics: time-in-range, mean glucose, GMI, CV [3] | Simple to understand; clinical familiarity | Oversimplifies dynamic patterns; misses nuanced phenotypes | Clinical glucose summary reports; population-level comparisons |

| Functional Data Analysis (FDA) | Treats CGM trajectories as mathematical functions; models temporal dynamics [3] | Captures complex temporal patterns; identifies subtle phenotypes | Requires statistical expertise; more complex implementation | Inter-day reproducibility analysis; glucose curve phenotype identification [11] |

| Machine Learning (ML) | Predictive modeling using algorithms; pattern recognition in time series [3] | Predicts future glucose levels; classifies metabolic states | Requires large datasets; potential overfitting | Hypoglycemia prediction; glucose trend classification [2] |

| Artificial Intelligence (AI) | Integrates ML with advanced algorithms; combines multiple data sources [3] | Enables real-time adaptive interventions; personalized recommendations | Data privacy concerns; regulatory hurdles; validation complexity | AI-powered closed-loop systems; personalized therapy optimization [3] |

Functional Data Analysis for Enhanced Pattern Recognition

Functional Data Analysis represents a fundamental shift in how CGM-acquired data is processed and interpreted. Unlike traditional statistics that treat glucose measurements as discrete points, FDA treats the entire CGM trajectory as a smooth curve evolving over time [3]. This approach offers several distinct advantages for research applications:

- Comprehensive Temporal Analysis: FDA models glucose dynamics as continuous processes rather than aggregated summaries, preserving information about the timing and shape of glycemic excursions [3].

- Enhanced Reproducibility Assessment: FDA enables quantification of inter-day reproducibility through functional intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs), which have demonstrated higher reproducibility in diabetic populations (ICC 0.46) compared to normoglycemic subjects (ICC 0.30) [11].

- Phenotype Identification: FDA facilitates identification of distinct glucose curve phenotypes based on their temporal characteristics rather than simple amplitude metrics, enabling more personalized intervention strategies [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

The development and validation of predictive models for interstitial glucose classification requires specific computational tools and methodological approaches. The following table outlines essential "research reagents" for this field.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Predictive Glucose Model Development

| Research Reagent | Function | Specific Examples/Applications |

|---|---|---|

| CGM Simulators | In silico testing of predictive algorithms | Simglucose v0.2.1; UVA/Padova T1D Simulator [2] |

| Functional Data Analysis Packages | Statistical analysis of CGM trajectories | Functional principal components analysis; glucodensity estimation [3] |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | Development of neural network models | CNN-LSTM architectures; BiLSTM with attention mechanisms [14] |

| Time Series Analysis Tools | Traditional statistical modeling of glucose data | ARIMA models; logistic regression for classification [2] |

| Model Evaluation Suites | Comprehensive performance assessment | Parkes Error Grid analysis; precision/recall metrics; MAPE calculation [14] |

| Data Preprocessing Pipelines | Quality control and feature engineering | Kalman smoothing; missing data imputation; stationarity testing [2] |

Multimodal Deep Learning Architecture

Continuous Glucose Monitoring systems have fundamentally transformed data acquisition for diabetes research, evolving from simple glucose tracking tools to sophisticated platforms for predictive analytics and personalized medicine. The comparative analysis of predictive interstitial glucose classification models reveals that model performance is highly dependent on both the quality of CGM-acquired data and the analytical methodology employed. While traditional statistical approaches provide foundational insights, advanced methods including Functional Data Analysis and multimodal deep learning architectures demonstrate superior performance, particularly for longer prediction horizons and personalized applications.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the selection of CGM technology and analytical approach must align with specific research objectives. Short-term prediction needs may be adequately served by logistic regression models, while longer-term forecasting and personalized applications benefit from LSTM networks and multimodal approaches that integrate physiological context. The ongoing innovation in CGM technology, including non-invasive sensors and extended-wear implants, promises to further enhance data acquisition capabilities, enabling more accurate and reliable predictive models that will continue to advance diabetes management and therapeutic development.

The accurate prediction of interstitial glucose levels represents a cornerstone of modern diabetes management, enabling proactive interventions to prevent hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia. However, the development of robust predictive models faces three fundamental challenges that impact reliability and clinical utility. Sensor delays create a physiological lag between blood and interstitial glucose readings, potentially delaying critical alerts. Signal artifacts introduced by sensor noise, calibration errors, and motion artifacts compromise data quality and accuracy. Physiological variability across individuals, influenced by factors such as metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and body composition, limits the generalizability of population-wide models. This comparative analysis examines how different modeling approaches address these challenges, providing researchers and drug development professionals with experimental data and methodological insights to guide algorithm selection and development.

Physiological Fundamentals and Technical Hurdles

The Blood-Interstitial Glucose Compartment Dynamics

The relationship between blood glucose (BG) and interstitial glucose (IG) concentrations is governed by complex physiological processes that directly contribute to sensor delays. Glucose is transferred from capillary endothelium to the interstitial fluid via simple diffusion across a concentration gradient without active transport [15]. This transfer process creates an inherent physiological lag, typically estimated at 5-15 minutes, though studies report variations from 0-45 minutes depending on measurement conditions [15] [16].

A two-compartment model mathematically describes these dynamics using the equation: dV₂G₂/dt = K₂₁V₁G₁ − (K₁₂ + K₀₂)V₂G₂, where G₁ represents plasma glucose concentration, G₂ represents interstitial glucose concentration, K₁₂ and K₂₁ represent forward and reverse flux rates across capillaries, K₀₂ represents glucose uptake into subcutaneous tissue, and V₁ and V₂ represent plasma and interstitial fluid volumes, respectively [15]. This physiological reality creates a fundamental challenge for real-time glucose monitoring, as CGM systems measure interstitial glucose but are calibrated to approximate blood glucose values, leading to discrepancies especially during periods of rapid glucose change [16].

Signal artifacts in continuous glucose monitoring arise from multiple sources, including both physiological and technical factors. Physiological artifacts include those caused by body movements, pressure on the sensor (compression hypoglycemia), and local metabolic variations at the sensor insertion site [2] [16]. The sensor insertion process itself causes local tissue trauma, provoking an inflammatory response that consumes glucose and creates a unstable microenvironment requiring a stabilization period before reliable measurements can be obtained [15].

Technical artifacts stem from electrochemical sensor limitations, calibration errors, and electromagnetic interference. Research demonstrates that sensor errors exhibit non-Gaussian distribution and are highly interdependent across consecutive measurements [16]. Furthermore, these errors display a nonlinear relationship with the rate of blood glucose change, with sensors tending to produce positive errors (overestimation) when BG trends downward and negative errors (underestimation) when BG trends upward, indicative of an underlying time delay [16].

Intersubject and Intraindividual Physiological Variability

Physiological variability presents a formidable challenge for generalized glucose prediction models. Studies reveal substantial differences in glucose metabolism and dynamics across individuals due to factors including age, body composition, insulin sensitivity, and medical conditions [15] [17]. Adiposity may particularly affect interstitial glucose concentrations because adipocyte size influences the amount of interstitial fluid in subcutaneous tissue [15].

This variability is further complicated by temporal fluctuations within the same individual based on activity level, stress, hormonal cycles, and other metabolic influences. The push-pull phenomenon describes how glucose moves from blood to interstitial space during rising glucose concentrations, but may be pulled from interstitial fluid to cells during declining periods, creating complex dynamics that violate simple compartment models [15]. This effect may explain observations that interstitial glucose can fall below plasma levels during insulin-induced hypoglycemia and remain depressed during recovery [15].

Comparative Analysis of Predictive Modeling Approaches

Experimental Frameworks and Evaluation Metrics

Research studies employ standardized methodologies to enable fair comparison across predictive models. Typical experimental protocols involve collecting continuous glucose monitor data alongside reference blood glucose measurements, often using venous blood samples analyzed via YSI instruments (CV = 2%) or fingerstick capillary blood measurements as comparators [16]. Studies commonly evaluate prediction horizons of 15 minutes, 30 minutes, 1 hour, and 2 hours to assess both immediate and medium-term forecasting capabilities [2] [6] [17].

The most frequently employed evaluation metrics include:

- Root Mean Square Error (RMSE): Measures the standard deviation of prediction errors

- Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE): Provides relative error assessment

- Precision, Recall, and F1-score: For classification into hypoglycemia, euglycemia, and hyperglycemia ranges

- Clarke Error Grid Analysis (CEGA): Assesses clinical significance of prediction errors

- Mean Absolute Relative Difference (MARD): Evaluates point accuracy against reference measurements

Performance is typically assessed using leave-one-subject-out cross-validation to evaluate generalizability across individuals and temporal validation on chronologically held-out data to simulate real-world deployment [9] [17].

Table 1: Standard Glucose Classification Ranges for Predictive Models

| Glucose State | Glucose Range | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Hypoglycemia | <70 mg/dL | Requires immediate intervention to prevent adverse events |

| Level 1 Hypoglycemia | 54-70 mg/dL | Clinically significant low glucose |

| Level 2 Hypoglycemia | <54 mg/dL | Serious, clinically important hypoglycemia |

| Euglycemia | 70-180 mg/dL | Target range for most individuals |

| Hyperglycemia | >180 mg/dL | Requires correction dosing |

Performance Comparison of Algorithmic Approaches

Different algorithmic approaches demonstrate distinct strengths and limitations in addressing the core challenges of glucose prediction. The comparative performance across multiple studies reveals consistent patterns in how various models handle sensor delays, artifacts, and physiological variability.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Glucose Prediction Models Across Multiple Studies

| Model Type | Prediction Horizon | Key Performance Metrics | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression [2] [6] | 15 minutes | Recall: Hypo 98%, Norm 91%, Hyper 96% | High short-term accuracy, computational efficiency, interpretability | Limited capacity for long-term predictions, struggles with complex temporal patterns |

| LSTM [2] [6] | 1 hour | Recall: Hypo 87%, Hyper 85% | Effective for longer prediction horizons, captures temporal dependencies | Requires substantial data, computationally intensive, prone to overfitting |

| Transformer-based Foundation Models (CGM-LSM) [17] | 1 hour | RMSE: 15.90 mg/dL (48.51% improvement) | Superior generalization, handles intersubject variability, transfer learning capability | Extreme computational requirements, complex implementation, limited interpretability |

| LightGBM with Feature Engineering [9] | 15 minutes | RMSE: 18.49 mg/dL, MAPE: 15.58% | Handles multimodal data, efficient with moderate datasets, robust to artifacts | Requires careful feature engineering, moderate performance with limited sensors |

| ARIMA [2] [6] | 15-60 minutes | Consistently underperformed other models | Statistical robustness, works with minimal data | Poor handling of rapid glucose variations, limited accuracy for extreme glucose events |

Specialized Approaches for Addressing Core Challenges

Sensor Delay Compensation Methods

Advanced modeling approaches specifically target the physiological delay between blood and interstitial glucose. Diffusion models of blood-to-interstitial glucose transport explicitly account for the time delay, while autoregressive moving average (ARMA) noise models address the interdependence of consecutive sensor errors [16]. Some research implements deconvolution techniques to mitigate sensor deviations resulting from the blood-to-interstitial time lag, effectively reconstructing blood glucose profiles from interstitial measurements [16].

Signal Artifact Handling

The channel attention mechanism demonstrates effectiveness in artifact management by weighting feature maps through integration of global average pooling and global max pooling layers, enhancing artifact-related features while suppressing noise [18]. Additionally, randomized dependence coefficient (RDC) measurements capture both linear and nonlinear dependencies between independent components and reference signals, improving detection of mixed or nonlinear artifact components in physiological signals [18].

Physiological Variability Mitigation

Large-scale foundation models pretrained on massive datasets (15.96 million glucose records from 592 patients) learn generalized glucose fluctuation patterns that transfer effectively to new patients, demonstrating consistent zero-shot prediction performance across held-out patient groups [17]. Personalized recalibration approaches and ensemble feature selection strategies that integrate recursive feature elimination with Boruta algorithms (BoRFE) further enhance model adaptation to individual physiological characteristics [9].

Emerging Approaches and Research Directions

Non-Invasive Monitoring and Multimodal Data Integration

Research increasingly explores non-invasive glucose monitoring using wearable devices that capture skin temperature (STEMP), blood volume pulse (BVP), heart rate (HR), electrodermal activity (EDA), and body temperature (BTEMP) [9]. While individual modalities show weak correlation with glucose changes (R² < 0.15), multimodal combinations demonstrate significantly improved predictive capability (R² = 0.90-0.96) [9]. This approach eliminates the need for invasive sensor insertion while potentially reducing calibration-related artifacts.

The experimental workflow for developing multimodal prediction models typically follows a structured pipeline:

Foundation Models and Transfer Learning

Inspired by large language models, Large Sensor Models (LSMs) represent a paradigm shift in glucose forecasting. The CGM-LSM model utilizes a transformer-decoder architecture trained autoregressively on massive CGM datasets, modeling patients as sequences of glucose time steps [17]. This approach demonstrates remarkable generalization capabilities, achieving a 48.51% reduction in RMSE for 1-hour horizon forecasting compared to conventional approaches, even on completely unseen patient data [17].

The architecture of foundation models for glucose prediction leverages advanced neural network designs:

Advanced Accuracy Assessment Methodologies

Traditional accuracy metrics like Mean Absolute Relative Difference (MARD) present limitations because they fail to account for the nonuniform relationship between error magnitude and glucose level [19]. Advanced Glucose Precision Profiles address this by representing accuracy and precision as smooth continuous functions of glucose level rather than step functions for discrete ranges [19]. These profiles reveal that MARD decreases systematically as glucose levels increase from 40 to 500 mg/dL, with traditional 3-4 range segmentation providing poor approximation of the underlying continuous relationship [19].

The Research Toolkit: Essential Methods and Technologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Glucose Prediction Research

| Tool Category | Specific Tools & Methods | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensor Platforms | Dexcom G6, Freestyle Libre, Medtronic Guardian | Generate continuous glucose data for model development | Different systems show measurement variations; consistency critical for comparisons [20] |

| Reference Methods | YSI 2300 Stat Plus Analyzer, Capillary Blood Glucose Meters | Provide ground truth for model training and validation | YSI instruments offer superior precision (CV=2%); capillary measurements more accessible [16] |

| Data Simulators | UVA/Padova T1D Simulator, Simglucose v0.2.1 | Generate synthetic data for algorithm testing and validation | Enable controlled experiments but may lack real-world complexity [2] |

| Feature Selection | Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), Boruta, BoRFE | Identify most predictive variables from multimodal data | Ensemble methods like BoRFE improve stability and performance [9] |

| Model Architectures | LSTM, Transformer, LightGBM, Random Forest | Core prediction algorithms with different capability profiles | Choice depends on data availability, prediction horizon, and computational resources [2] [17] |

| Evaluation Frameworks | Clarke Error Grid, Precision Profiles, LOSO-CV | Assess clinical relevance and generalizability of predictions | Subject-independent validation essential for real-world performance estimation [19] [9] |

The comparative analysis of predictive interstitial glucose classification models reveals significant advances in addressing the fundamental challenges of sensor delays, signal artifacts, and physiological variability. Foundation models and multimodal approaches demonstrate particular promise in handling intersubject variability, while specialized attention mechanisms and artifact detection algorithms show improved resilience to signal quality issues. Nevertheless, important research gaps remain. Prediction accuracy consistently declines during high-variability contexts such as mealtimes, physical activity, and extreme glucose events [17]. The interpretability and clinical trust of complex models like transformers present implementation barriers. Furthermore, personalization techniques that efficiently adapt general models to individual physiology without extensive recalibration data require further development. Future research directions should prioritize robustness in edge cases, computational efficiency for real-time implementation, and standardized evaluation protocols that enable direct comparison across studies. By addressing these challenges, next-generation glucose prediction models will enhance their clinical utility and contribute to improved outcomes in diabetes management.

The Impact of Prediction Horizon on Clinical Utility (e.g., 15-minute vs. 1-hour forecasts)

In the management of diabetes, the ability to accurately forecast future glucose levels is a cornerstone for preventative interventions. The prediction horizon (PH)—how far into the future a forecast is made—is a critical determinant of a model's clinical utility. Short-term (e.g., 15-minute) and medium-term (e.g., 1-hour) forecasts enable different clinical actions, from immediate hypoglycemia avoidance to longer-term dietary or insulin adjustments. This guide provides a comparative analysis of predictive model performance across these horizons, synthesizing experimental data to inform researchers and drug development professionals selecting models for specific clinical applications.

Quantitative Comparison of Model Performance by Prediction Horizon

The performance of predictive models varies significantly based on the chosen prediction horizon. The following tables consolidate key quantitative metrics from recent studies to facilitate a direct comparison.

Table 1: Performance of Classification Models for Hypo-/Normo-/Hyperglycemia [2]

| Model | Prediction Horizon | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | 15 minutes | 96 (Hyper) | 96 (Hyper) | 96 (Hyper) | >95 |

| 91 (Normo) | 91 (Normo) | 91 (Normo) | |||

| 98 (Hypo) | 98 (Hypo) | 98 (Hypo) | |||

| LSTM | 1 hour | 85 (Hyper) | 85 (Hyper) | 85 (Hyper) | >80 |

| 87 (Hypo) | 87 (Hypo) | 87 (Hypo) | |||

| ARIMA | 15 min & 1 hour | Underperformed logistic regression and LSTM for all classes |

Note: Hypoglycemia: <70 mg/dL; Euglycemia: 70–180 mg/dL; Hyperglycemia: >180 mg/dL.

Table 2: Performance of Regression Models for Continuous Glucose Prediction [21] [22] [23]

| Model | Prediction Horizon | RMSE (mg/dL) | Dataset | Key Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PatchTST | 30 minutes | 15.6 | OhioT1DM | Septic Patient [24] |

| 1 hour | 24.6 | OhioT1DM | ||

| 2 hours | 36.1 | OhioT1DM | ||

| 4 hours | 46.5 | OhioT1DM | ||

| Crossformer | 30 minutes | 15.6 | OhioT1DM | |

| DLinear | 30 minutes | 7.46% (MMPE) | Patient-specific | Septic Patient [24] |

| 60 minutes | 14.41% (MMPE) | Patient-specific | Septic Patient [24] | |

| LightGBM (with Feature Engineering) | 15 minutes | 18.49 | Healthy Cohort | Non-invasive wearables [9] |

Note: RMSE (Root Mean Square Error); MMPE (Mean Maximum Percentage Error).

Experimental Protocols for Cited Studies

The quantitative data presented above are derived from rigorous experimental methodologies. Below is a detailed breakdown of the key protocols.

- Objective: To compare the efficacy of ARIMA, Logistic Regression, and LSTM models in classifying future glucose states (hypo-, normo-, hyperglycemia) at 15-minute and 1-hour horizons.

- Data Source: A hybrid dataset was used, combining:

- Clinical Data: CGM data from 11 participants with type 1 diabetes from the "COVAC-DM" study (EudraCT: 2021-001459-15).

- In-Silico Data: The Simglucose (v0.2.1) Python implementation of the UVA/Padova T1D Simulator, generating data for 30 virtual patients (adults, adolescents, children) over 10 days.

- Data Preprocessing: Raw data was cleaned and brought to a consistent 15-minute frequency. Glucose values were mapped into the three clinical classes.

- Model Training & Evaluation: Models were trained to predict the glucose class at future time points. Performance was evaluated using confusion matrices, with precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy calculated for each class and prediction horizon.

- Objective: To conduct a comparative analysis of transformer-based models for multi-horizon blood glucose prediction, examining forecasts up to 4 hours.

- Data Source:

- Primary Dataset: The public DCLP3 dataset (n=112) was split 80%-10%-10% for training, validation, and testing.

- External Test Set: The OhioT1DM dataset (n=12) was used for final evaluation to assess generalizability.

- Input Data: Multivariate time-series data including CGM readings, insulin data, and meal information.

- Model Variants: The study compared several transformer embedding approaches:

- Point-wise: Vanilla Transformer

- Patch-wise: Crossformer, PatchTST

- Series-wise: iTransformer

- Hybrid: TimeXer

- Evaluation: Models were evaluated across different history lengths (4h to 1 week) and prediction horizons (30, 60, 120, 240 minutes). The primary metric was RMSE (mg/dL) on the external OhioT1DM test set.

Workflow and Decision Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the typical experimental workflow for developing and evaluating glucose prediction models, from data acquisition to clinical utility assessment.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for glucose prediction models, showing the pathway from data acquisition to clinical utility assessment.

The choice of model is often dictated by the target prediction horizon. The following logic can guide researchers in selecting an appropriate model based on their primary clinical goal.

Figure 2: A decision pathway for selecting a glucose prediction model based on the target prediction horizon and clinical goal.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Datasets for Glucose Prediction Research

| Item Name | Type & Function | Example in Research / Source |

|---|---|---|

| CGM Device | Hardware: Provides continuous, real-time interstitial glucose measurements. | FreeStyle Libre (Abbott) used in multiple studies [25] [26]. |

| Public Datasets | Data: Essential for training, validating, and benchmarking models. | OhioT1DM [21] [23], DCLP3 [21] [23], ShanghaiDM [25]. |

| In-Silico Simulator | Software: Generates synthetic patient data for initial algorithm testing. | Simglucose (UVA/Padova T1D Simulator) [2]. |

| Non-Invasive Wearables | Hardware: Captures physiological data (e.g., HR, EDA) for non-invasive prediction. | Devices measuring Skin Temp, BVP, EDA, HR used to predict glucose without CGM [9]. |

| Tree-Based Algorithms | Software/Model: Provides a strong, interpretable baseline for prediction tasks. | LightGBM and Random Forest, used for feature selection and prediction [9]. |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | Software/Model: Enables building complex models for capturing temporal patterns. | LSTM [2] [9] and Transformer architectures (PatchTST, Crossformer) [21] [23] [24]. |

The management of diabetes has been revolutionized by Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) systems, which provide real-time alerts for hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, significantly improving glycemic control during meals and physical activity [6] [2]. However, the complexity of CGM systems presents substantial challenges for both individuals with diabetes and healthcare professionals, particularly in interpreting rapidly changing glucose levels, dealing with sensor delays (approximately a 10-minute difference between interstitial and plasma glucose readings), and addressing potential malfunctions [27] [2]. The development of advanced predictive glucose level classification models has therefore become imperative for optimizing insulin dosing and managing daily activities, forming a critical component of personalized diabetes management strategies [6].

Within this context, establishing robust baseline models provides an essential foundation for evaluating more complex artificial intelligence approaches. Foundational statistical and machine learning models, particularly Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) and Logistic Regression, serve as critical benchmarks in the comparative analysis of predictive interstitial glucose classification. These models offer distinct advantages in interpretability, computational efficiency, and implementation simplicity, making them indispensable references against which to assess the performance of more complex deep learning architectures [6] [28]. This guide presents a comprehensive objective comparison of these foundational approaches, providing researchers and clinicians with experimental data and methodologies essential for advancing glucose prediction research.

Experimental Foundations: Methodologies for Model Comparison

Data Collection and Preprocessing Protocols

The comparative analysis of glucose prediction models requires rigorously standardized data collection and preprocessing methodologies. The foundational studies examined herein utilized data from both clinical cohorts and sophisticated simulation environments [27] [2]. Clinical CGM data were typically acquired from studies involving participants with type 1 diabetes, with data collected at 15-minute intervals and including additional parameters such as insulin dosing and carbohydrate intake [2] [28]. To complement real-world data, researchers frequently employed the CGM Simulator (Simglucose v0.2.1), a Python implementation of the UVA/Padova T1D Simulator that generates in-silico data for virtual patients across different age groups, spanning multiple days with randomized meal and snack patterns [27] [28].

A critical preprocessing pipeline ensured data quality and consistency:

- Temporal Alignment: Raw data with minor frequency variability was processed to maintain strict 15-minute intervals, with linear interpolation applied to gaps shorter than 30 minutes [28] [29].

- Feature Engineering: Beyond raw glucose values, researchers derived multiple feature categories including rolling averages (5, 15, 30, and 60-minute windows), glucose velocity and acceleration, time-based features (time of day, hour, minute), and statistical measures (rolling standard deviation, minimum, and maximum) [27].

- Data Partitioning: For model evaluation, patient data was typically split into in-sample and out-of-sample sets, with chronological preservation to prevent temporal information leakage [28].

Model Specification and Training Methodologies

ARIMA Model Configuration

ARIMA models were implemented as univariate time series predictors using only historical CGM values [28] [29]. The model order parameters (p, d, q) were determined through grid search optimized by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), with model diagnostics including residual autocorrelation and stationarity tests (Augmented Dickey-Fuller) [29]. The ARIMA forecasts generated future CGM values, which were subsequently classified into glycemic states using standardized thresholds [28].

Logistic Regression Implementation

Multinomial logistic regression models were configured to directly predict glucose level classification using engineered features and their lagged values (with lags up to 12 time points) [28]. The models were trained to maximize the multinomial likelihood, with glycemic states defined as hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL), euglycemia (70-180 mg/dL), and hyperglycemia (>180 mg/dL) [6] [2]. Regularization techniques were often employed to prevent overfitting in these feature-rich environments [29].

LSTM Reference Implementation

While not a foundational model, LSTM networks served as an advanced reference point in the comparative studies. These networks were typically implemented with one or two hidden layers, utilizing sequence lengths covering 60-180 minutes of historical data [6]. The models were trained using backpropagation through time, with dropout regularization applied to improve generalization [28].

Evaluation Framework and Metrics

Model performance was assessed using a comprehensive set of classification metrics calculated from out-of-sample predictions [28]. The evaluation framework included:

- Recall (Sensitivity): The proportion of actual cases in each glycemia class correctly identified, particularly crucial for hypoglycemia detection [6] [2].

- Precision: The proportion of correct predictions among all predictions for each glycemia class [6].

- Accuracy: The overall proportion of correct predictions across all classes [28].

- F1-Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall [28].

- Clarke Error Grid Analysis (CEG): Clinical risk assessment categorizing prediction errors into zones indicating clinical significance [9] [29].

Performance was evaluated at multiple prediction horizons (15 minutes and 60 minutes) to assess temporal robustness, with statistical significance testing via Diebold-Mariano or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests [29].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for comparative analysis of glucose prediction models, covering data collection, model development, and evaluation phases.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The comparative performance of ARIMA, logistic regression, and LSTM models across critical prediction horizons reveals distinct patterns of strengths and limitations.

Table 1: Model Performance Comparison at 15-Minute Prediction Horizon

| Glucose Class | Model | Recall (%) | Precision (%) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL) | Logistic Regression | 98 | 96 | 97 |

| LSTM | 88 | 85 | 87 | |

| ARIMA | 42 | 38 | 41 | |

| Euglycemia (70-180 mg/dL) | Logistic Regression | 91 | 94 | 92 |

| LSTM | 84 | 88 | 85 | |

| ARIMA | 76 | 72 | 74 | |

| Hyperglycemia (>180 mg/dL) | Logistic Regression | 96 | 92 | 95 |

| LSTM | 90 | 87 | 89 | |

| ARIMA | 65 | 61 | 63 |

Table 2: Model Performance Comparison at 60-Minute Prediction Horizon

| Glucose Class | Model | Recall (%) | Precision (%) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL) | LSTM | 87 | 83 | 85 |

| Logistic Regression | 83 | 79 | 81 | |

| ARIMA | 7 | 5 | 6 | |

| Euglycemia (70-180 mg/dL) | LSTM | 80 | 84 | 81 |

| Logistic Regression | 75 | 79 | 76 | |

| ARIMA | 63 | 58 | 61 | |

| Hyperglycemia (>180 mg/dL) | LSTM | 85 | 81 | 83 |

| Logistic Regression | 78 | 74 | 76 | |

| ARIMA | 60 | 55 | 58 |

The data reveals several critical patterns. For short-term predictions (15 minutes), logistic regression demonstrates exceptional performance, particularly for hypoglycemia detection with 98% recall, substantially outperforming both LSTM (88%) and ARIMA (42%) [6] [28]. This superiority extends across all glycemia classes at this horizon, highlighting its effectiveness for immediate-term forecasting. However, for longer-term predictions (60 minutes), LSTM models outperform logistic regression, achieving 87% recall for hypoglycemia compared to 83% for logistic regression [6] [2]. ARIMA consistently underperforms across all categories and time horizons, particularly struggling with hypoglycemia prediction at 60 minutes (7% recall) [28].

Figure 2: Model selection framework based on prediction horizon requirements and performance characteristics.

Clinical Relevance and Error Profile Analysis

Beyond traditional metrics, clinical applicability was assessed through Clarke Error Grid Analysis (CEG), which categorizes prediction errors based on their potential clinical significance [9]. Studies implementing ridge regression (conceptually similar to regularized logistic regression) demonstrated that approximately 96% of predictions fell into Clarke Zone A (clinically accurate), with the remaining 4% in Zone B (benign errors) [29]. This performance profile supports the clinical utility of these models for real-world decision support.

The comparative error analysis reveals that ARIMA models struggle particularly with rapid glucose transitions, failing to capture non-linear dynamics essential for predicting hypoglycemic and hyperglycemic events [28]. Logistic regression exhibits robust performance during stable glycemic periods but shows some degradation during periods of high glycemic variability. LSTM models demonstrate superior capability in capturing complex temporal patterns, contributing to their enhanced longer-horizon performance [6].

Research Reagent Solutions: Experimental Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Resources for Glucose Prediction Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Platform | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| CGM Data Sources | OhioT1DM Dataset [30] [29] | Public benchmark for model development & validation | Multi-subject CGM data, 5-min resolution, paired with insulin, carbs, activity |

| FreeStyle Libre [9] [20] | Clinical data collection | Factory-calibrated, 15-min sampling, real-world accuracy validation | |

| Dexcom G6 [20] | High-accuracy reference data | Calibration requirements, clinical grade accuracy assessment | |

| Simulation Platforms | Simglucose v0.2.1 [27] [2] | In-silico testing & validation | Python implementation of FDA-approved UVA/Padova simulator, virtual patients |

| UVA/Padova T1D Simulator [28] | Metabolic modeling & control testing | Gold-standard metabolic simulation, accepted by regulatory authorities | |

| Programming Frameworks | Python Scikit-learn [29] | Traditional ML implementation | Logistic regression, feature engineering, model evaluation utilities |

| Python Statsmodels [29] | Statistical modeling | ARIMA implementation, time series analysis, statistical testing | |

| TensorFlow/PyTorch [6] [9] | Deep learning development | LSTM implementation, neural network training, GPU acceleration | |

| Evaluation Frameworks | Clarke Error Grid Analysis [9] [29] | Clinical risk assessment | Standardized clinical accuracy evaluation, error classification |

| RMSE/MAE/MAPE [9] [30] | Numerical accuracy metrics | Standard regression metrics, performance quantification |

This comparative analysis establishes ARIMA and logistic regression as essential foundational models in the landscape of predictive interstitial glucose classification. The experimental evidence demonstrates that model selection must be guided by the specific clinical requirements and prediction horizon needs. Logistic regression emerges as the superior choice for short-term predictions (15 minutes), offering exceptional performance particularly for hypoglycemia detection while maintaining computational efficiency and interpretability [6] [2]. In contrast, ARIMA models demonstrate significant limitations across most application scenarios, particularly for critical hypoglycemia prediction at extended horizons [28].

These foundational models provide critical baselines against which to evaluate more complex artificial intelligence approaches. The documented performance metrics and methodological frameworks offer researchers standardized benchmarks for comparative studies. Future research directions should explore hybrid modeling approaches that leverage the strengths of both logistic regression (interpretability, short-term accuracy) and LSTM networks (temporal modeling, long-term forecasting), potentially enhanced through ensemble methods and adaptive framework [6]. Additionally, increasing attention to model interpretability, demographic diversity in training data, and real-world clinical validation will be essential for advancing the field toward equitable and effective personalized glucose management systems [25].

Algorithmic Approaches: Implementing Traditional ML and Deep Learning Models

The management of diabetes has been revolutionized by continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), which provides real-time insights into interstitial glucose levels. A critical challenge in this domain is the accurate prediction of future glycemic states—hypoglycemia, euglycemia, and hyperglycemia—to enable proactive interventions. Machine learning (ML) models are uniquely suited to this task, capable of identifying complex patterns in physiological data. Among the diverse ML landscape, three algorithms consistently feature prominently in predictive healthcare tasks: Logistic Regression, Random Forest, and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost). This guide provides a comparative analysis of these three models within the specific context of predictive interstitial glucose classification, drawing on recent experimental studies to objectively evaluate their performance, optimal application contexts, and implementation protocols.

The fundamental differences between these algorithms lie in their underlying structure and learning approach, which directly influence their performance in glucose prediction tasks.

Logistic Regression (LR) is a linear model that estimates the probability of a categorical outcome. It operates by applying a sigmoid function to a linear combination of the input features, making it highly interpretable as the impact of each feature on the prediction is directly quantifiable through its coefficient [31] [2]. However, this linearity is also its primary limitation, as it cannot automatically capture complex non-linear relationships or interactions between features without manual engineering [31].

Random Forest (RF) is an ensemble method based on the "bagging" principle. It constructs a multitude of decision trees during training, each built on a random subset of the data and features. The final prediction is determined by majority voting (classification) or averaging (regression) across all trees [32]. This architecture reduces the risk of overfitting, which is common with a single decision tree, and generally leads to robust performance with minimal hyperparameter tuning [31] [32].

XGBoost (eXtreme Gradient Boosting) is also a tree-based ensemble method, but it uses a "boosting" framework. Unlike RF's parallel tree construction, XGBoost builds trees sequentially, with each new tree designed to correct the errors made by the previous sequence of trees [32]. It combines this with a gradient descent algorithm to minimize a regularized loss function, which includes penalties for model complexity (L1 and L2 regularization). This makes XGBoost particularly powerful for achieving high predictive accuracy, though it can be more prone to overfitting if not carefully regularized [31] [32].

The following diagram illustrates the core structural and procedural differences in how these models operate.

Performance Comparison in Glucose Classification

Empirical evidence from recent studies highlights the performance trade-offs between these models. The following table summarizes key quantitative results from experiments in glucose classification and related medical prediction tasks.

Table 1: Performance Comparison Across Predictive Healthcare Studies

| Study Context | Model | Key Performance Metrics | Feature Selection Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air Quality Index Classification [33] | XGBoost | Accuracy: 98.91% | Pearson Correlation |

| Random Forest | Accuracy: 97.08% | Pearson Correlation | |

| Logistic Regression | Performance suffered with feature elimination | Pearson Correlation | |

| AKI Post-Cardiac Surgery [34] | Gradient Boosted Trees | Accuracy: 88.66%, AUC: 94.61%, Sensitivity: 91.30% | Univariate Analysis & Data Patterns |

| Random Forest | Accuracy: 87.39%, AUC: 94.78% | Univariate Analysis & Data Patterns | |

| Logistic Regression | Balanced Sensitivity (87.70%) and Specificity (87.05%) | Univariate Analysis & Data Patterns | |

| Hyperglycemia Prediction (Hemodialysis) [4] | Logistic Regression | F1 Score: 0.85, ROC-AUC: 0.87 | Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) |

| XGBoost | Lower performance than LR for this specific task | Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | |

| Hypoglycemia Prediction (Hemodialysis) [4] | TabPFN (Transformer) | F1 Score: 0.48, ROC-AUC: 0.88 | Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) |

| XGBoost | Lower performance than TabPFN for this task | Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | |

| Difficult Laryngoscopy Prediction [35] | Random Forest | AuROC: 0.82, Accuracy: 0.89, Recall: 0.89 | Multivariable Stepwise Backward Elimination |

| XGBoost | Strong Precision | Multivariable Stepwise Backward Elimination | |

| Logistic Regression | AuROC: 0.76 | Multivariable Stepwise Backward Elimination |

A synthesis of these results and other studies reveals consistent performance characteristics, which are summarized below.

Table 2: Overall Model Characteristics for Glucose Classification Tasks

| Criterion | Logistic Regression | Random Forest | XGBoost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interpretability | High (Transparent coefficients) [31] | Medium (Feature importance available) [31] | Low (Complex, sequential model) [31] |

| Handling Non-Linearity | Poor (Requires feature engineering) [31] | Good (Native non-linear handling) [31] | Excellent (Native non-linear handling) [31] |

| Computational Cost | Very Low [31] [36] | Moderate [31] [32] | High [31] [32] |

| Handling Imbalance | Via class_weight parameter [31] |

Via class_weight or resampling [31] |

Via scale_pos_weight & resampling [31] |

| Typical Recall (Minority Class) | Low–Moderate [31] | Moderate–High [31] | High [31] |

| Best Suited For | Baselines, interpretability-critical tasks, linear relationships [31] [2] | Robust, general-purpose use with minimal tuning [31] [35] | Maximizing predictive accuracy on complex, structured data [33] [31] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure the reproducibility of comparative analyses, this section outlines the standard methodologies employed in the cited studies.

Data Preprocessing and Feature Selection

A consistent preprocessing pipeline is crucial for a fair model comparison. The following workflow visualizes the standard protocol from data collection to model evaluation, as implemented across multiple studies [34] [4].

Data Sources and Collection: Studies typically use CGM data streams, often augmented with patient demographics (age, weight), clinical variables (HbA1c, insulin use), and sometimes data on carbohydrate intake and physical activity [2] [4]. Data can come from real patient cohorts or in-silico simulators like the UVA/Padova T1D Simulator [2].

Preprocessing: A critical step is addressing class imbalance, which is common in medical datasets (e.g., hypoglycemic events are rare). Techniques like the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) are frequently applied to generate synthetic samples of the minority class, preventing models from ignoring it [34].

Feature Engineering: For glucose prediction, features derived from the CGM signal itself are highly informative. These include the rate of change (ROC), moving averages, variability indices, and time-since-last-meal or -insulin-bolus [2]. In studies using wearables, features from modalities like skin temperature (STEMP), electrodermal activity (EDA), and heart rate (HR) are also extracted [9].

Feature Selection: Applying feature selection improves model performance and interpretability. The Pearson Correlation method removes features weakly correlated with the target, which has been shown to particularly benefit tree-based models like RF and XGBoost [33]. Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is an iterative method that recursively removes the least important features [4].

Model Training and Evaluation Criteria

Training Protocol: A standard hold-out validation approach involves splitting the dataset into a training set (e.g., 70-80%) and a testing set (e.g., 20-30%) [35]. For a more robust validation, especially with limited data, Leave-One-Participant-Out Cross-Validation (LOPOCV) is preferred in glucose prediction studies [9]. This method ensures that data from a single patient is exclusively in the test set for each fold, effectively evaluating model generalizability to new, unseen individuals.

Hyperparameter Tuning: Model hyperparameters are optimized using techniques like random search or Bayesian optimization on the training/validation sets [36] [4]. Key parameters include:

- Logistic Regression: Regularization strength (

C), penalty type (L1/L2). - Random Forest: Number of trees (

n_estimators), maximum tree depth (max_depth). - XGBoost: Learning rate (

eta),max_depth,scale_pos_weight(for imbalanced data) [31], and L1/L2 regularization terms.

Evaluation Metrics: Given the clinical stakes, a comprehensive set of metrics is used:

- Accuracy: Overall correctness, but can be misleading for imbalanced data [31].

- Precision & Recall (Sensitivity): Critical for assessing performance on the minority class (e.g., hypoglycemia). High recall ensures most true events are captured.

- F1-Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall.

- AUC-ROC: Measures the model's ability to distinguish between classes.

- Clinical Metrics: Clarke Error Grid Analysis (CEGA) is a zone-based metric that evaluates the clinical accuracy of glucose predictions, categorizing errors based on their potential to lead to inappropriate treatment decisions [9].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental protocols rely on a suite of computational "reagents" – software tools and datasets that are fundamental to conducting research in this field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Comparative ML Studies in Glucose Prediction

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| RapidMiner [34] | Software Platform | End-to-end data science platform for data preprocessing, model training, and validation. | Used for applying SMOTE and building/tuning models like Logistic Regression and Random Forest [34]. |

| Python (Scikit-learn, XGBoost) [2] | Programming Library | Open-source libraries providing implementations of ML algorithms and utilities. | Custom implementation of model training pipelines, hyperparameter tuning, and evaluation [2]. |

| UVA/Padova T1D Simulator [2] | In-Silico Dataset | A widely accepted simulator of glucose metabolism in T1D, generating synthetic CGM and patient data. | Provides a large, standardized dataset for initial model development and testing in a controlled environment [2]. |

| OhioT1DM / ShanghaiDM [9] [25] | Public Dataset | Real-world CGM datasets collected from individuals with diabetes, often including other sensor data. | Used for validating model performance on real patient data outside of simulated environments [9] [25]. |

| SMOTE [34] | Algorithmic Tool | A preprocessing technique to generate synthetic samples of the minority class in a dataset. | Crucial for handling the inherent class imbalance in hypoglycemia prediction tasks to improve model recall [34]. |

| Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) [4] | Algorithmic Tool | A feature selection method that recursively builds models and removes the weakest features. | Improves model interpretability and performance by eliminating non-informative predictors before training [4]. |

The comparative analysis of Logistic Regression, Random Forest, and XGBoost demonstrates that there is no single "best" model for all scenarios in glucose classification. The choice of algorithm is a strategic decision that must align with the specific research or clinical objective. XGBoost consistently achieves the highest predictive accuracy in complex tasks with sufficient data and computational resources [33] [31]. Random Forest offers a robust, well-balanced alternative with strong performance and reduced risk of overfitting, making it an excellent general-purpose model [35] [32]. Logistic Regression remains a vital tool for establishing performance baselines and in situations where model interpretability is paramount, or when the underlying relationships are approximately linear [31] [2] [4]. Ultimately, the selection process should be guided by a clear understanding of the trade-offs between accuracy, interpretability, computational efficiency, and the specific clinical question at hand.

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Units (GRU)

In the field of deep learning for sequential data, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Units (GRU) represent two pivotal architectural evolutions designed to overcome the vanishing gradient problem inherent in traditional Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs). These architectures have become fundamental tools for modeling temporal dependencies across diverse domains, from healthcare to climate science and engineering. Within the specific context of predictive interstitial glucose classification, the selection between LSTM and GRU involves critical trade-offs between model complexity, computational efficiency, and predictive accuracy. This guide provides an objective comparison of LSTM and GRU architectures, underpinned by experimental data and detailed methodological insights, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in their model selection process for glucose prediction and related time-series forecasting tasks.

The core innovation of both LSTM and GRU networks lies in their gating mechanisms, which regulate the flow of information through the sequence, enabling them to capture long-range dependencies more effectively than simple RNNs.

LSTM Architecture

Long Short-Term Memory networks introduce a sophisticated memory cell structure with three distinct gates [37]:

- Forget Gate: Determines what information should be discarded from the cell state.

- Input Gate: Controls which new information should be stored in the cell state.

- Output Gate: Regulates what parts of the cell state should be output at the current timestep.

This three-gate system, coupled with a separate cell state that acts as a "conveyor belt" for information, allows LSTMs to maintain and access relevant information over extended sequences, making them particularly powerful for modeling complex temporal relationships [37].

GRU Architecture

Gated Recurrent Units simplify the LSTM approach by combining the input and forget gates into a single update gate, resulting in a more streamlined architecture with only two gates [38]:

- Update Gate: Balances the influence of previous hidden state information with new candidate information.

- Reset Gate: Determines how much of the previous hidden state should be ignored when computing the new candidate state.

GRUs eliminate the separate cell state, using only the hidden state to transfer information, which reduces architectural complexity and computational requirements while maintaining competitive performance on many sequence modeling tasks [37] [38].

Performance Comparison in Time Series Forecasting

Empirical evaluations across diverse domains reveal nuanced performance differences between LSTM and GRU architectures, with outcomes significantly influenced by dataset characteristics and task requirements.

Quantitative Benchmarking Results

Table 1: Comprehensive performance comparison of LSTM and GRU across domains

| Application Domain | Dataset/Context | LSTM Performance | GRU Performance | Performance Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sea Level Prediction | Ulleungdo Island Tide Data | Higher RMSE | RMSE ≈0.44 cm | GRU demonstrated superior predictive accuracy and training stability | [39] |