Closed-Loop Control System Design for the Artificial Pancreas: From Foundational Algorithms to Clinical Implementation

This article provides a comprehensive review of the engineering and algorithmic foundations of Artificial Pancreas (AP) systems for automated glucose management in diabetes.

Closed-Loop Control System Design for the Artificial Pancreas: From Foundational Algorithms to Clinical Implementation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of the engineering and algorithmic foundations of Artificial Pancreas (AP) systems for automated glucose management in diabetes. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the evolution of closed-loop control from seminal concepts to contemporary hybrid and fully automated systems. The scope encompasses core control methodologies like Model Predictive Control (MPC) and PID, the rise of data-driven approaches including deep reinforcement learning, and the integration of feedforward mechanisms for meal and exercise disturbance rejection. It further details performance validation through clinical trials and in-silico simulations, analyzes prevailing challenges in safety and personalization, and discusses future trajectories involving dual-hormone systems, advanced artificial intelligence, and cyber-physical-human frameworks for precision medicine.

The Evolution of Automated Glycemic Control: From Concept to Standard of Care

The development of the Artificial Pancreas (AP) represents a landmark achievement in the treatment of Type 1 Diabetes (T1D), transforming a once-disputed concept into today's standard of care [1]. This revolutionary technology automates blood glucose management through integrated continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) and insulin delivery, significantly reducing the daily burden of diabetes self-care [2] [3]. The journey from theoretical concept to viable commercial systems spans decades of dedicated research, engineering innovation, and collaborative clinical testing, largely accelerated by strategic support from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF), now known as Breakthrough T1D [1] [4]. This application note traces the critical developmental pathway of closed-loop systems, documenting key historical milestones, experimental paradigms, and technical specifications to inform ongoing research and development in automated insulin delivery.

Historical Timeline and Key Events

The evolution of artificial pancreas technology has progressed through distinct phases of conceptualization, research, development, and commercialization. The following table summarizes the major milestones in this journey:

Table 1: Historical Milestones in Artificial Pancreas Development

| Year | Milestone Event | Significance | Key Participants/Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | First NIH/JDRF Workshop: "Obstacles and Opportunities on the Road to Artificial Pancreas" [1] | Initiated coordinated movement toward solving AID challenges; room divided on viability of subcutaneous CGM/CSII approach [1] | NIH, JDRF, FDA |

| 2006 | JDRF Artificial Pancreas Project Launch [1] | Issued Request for Applications to initiate formal AP research program [1] | JDRF (Breakthrough T1D) |

| 2007 | First Closed-Loop Human Trial in U.S. [1] | APS platform enabled first U.S. closed-loop human subject trial at UCSB [1] | University of California, Santa Barbara |

| 2008 | FDA Acceptance of Computer Simulator [1] | Accepted simulator as substitute for animal trials, accelerating development by years [1] | Universities of Padova and Virginia, FDA |

| 2008-2012 | Outpatient Studies Progress [1] | Systems tested in camp settings (2008) then patients' homes (2010) [1] | Multiple academic centers |

| 2011 | Diabetes Assistant Platform [1] | First portable AP platform using Android smartphone as computational hub [1] | University of Virginia |

| 2016 | First Commercial Hybrid System FDA Approval [5] | MiniMed 670G became first hybrid closed-loop system cleared for clinical use [5] | Medtronic (670G system) |

| 2016-2018 | Research Publication Peak [1] | >150 publications/year on closed-loop systems; AP "coming of age" [1] | Global research community |

| 2019-2024 | Second-Generation Systems & Algorithm Advancements [6] [7] | Introduction of systems with more adaptive algorithms and simpler initialization [6] | Tandem, Insulet, Beta Bionics |

The progression from concept to clinical adoption demonstrates the effective integration of engineering and medicine. Initial systems utilizing laptop computers were cumbersome and unsuitable for routine outpatient use [1], while contemporary systems leverage sophisticated miniaturized technology with embedded control algorithms [7].

Technical Evolution of AP Systems

System Architecture and Components

Modern Artificial Pancreas systems integrate three core components: a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), an insulin pump, and a control algorithm that functions as the system's decision-making center [2]. The CGM measures interstitial glucose levels via a subcutaneous electrode, transmitting data to a receiver or smart device. Modern sensors like Dexcom G7 and Abbott's FreeStyle Libre 3 offer Mean Absolute Relative Difference (MARD) under 9% and require no calibration [2]. Insulin pumps deliver fast-acting insulin analogues subcutaneously, with modern systems allowing programmable basal rates and bolus profiles [2]. The control algorithm represents the most critical innovation, continuously adjusting insulin infusion based on real-time glucose data and predictive modeling [2].

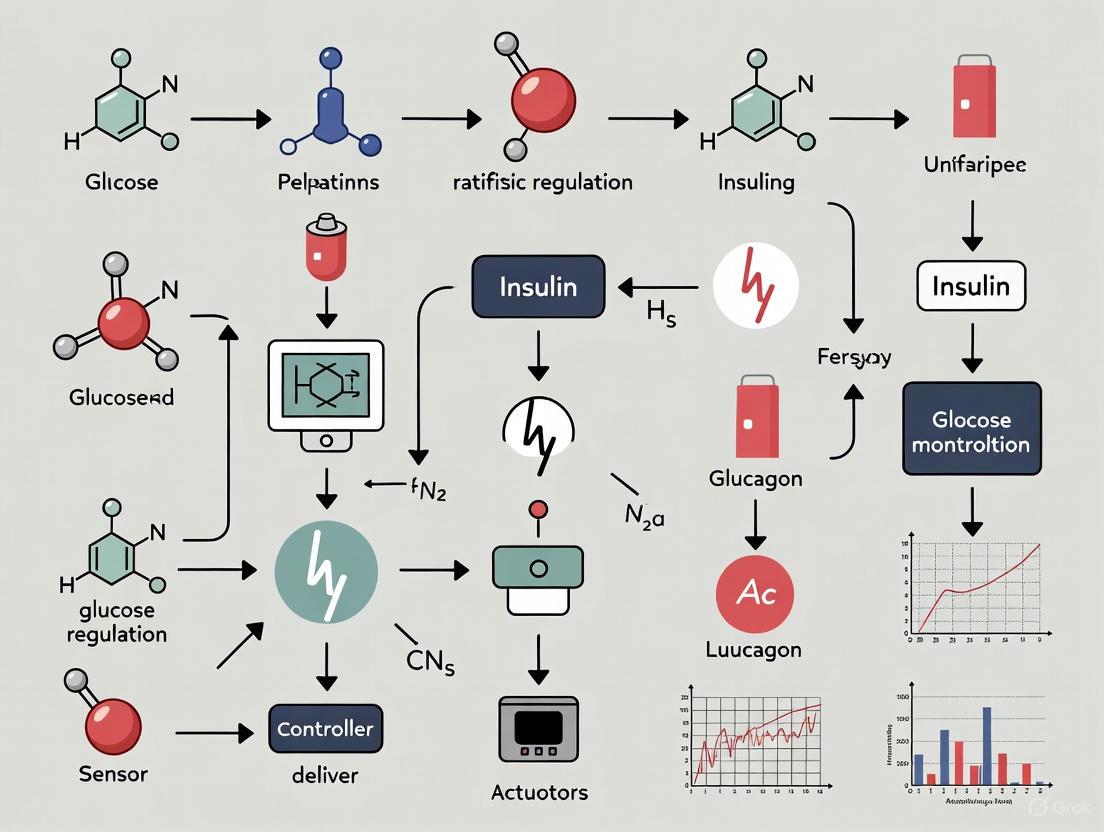

Figure 1: Artificial Pancreas Closed-Loop Control System. The system continuously monitors glucose levels and automatically adjusts insulin delivery in response to real-time data and external disturbances.

Control Algorithm Evolution

Control algorithms have evolved significantly from early prototypes to contemporary sophisticated systems. The two primary algorithm types are Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) and Model Predictive Control (MPC) [2]. PID controllers adjust insulin delivery based on current glucose level (proportional), the area under the curve between measured and target glucose (integral), and the rate of change of measured glucose (derivative) [2]. MPC utilizes mathematical models to predict future glucose trajectories and optimize insulin dosing accordingly [2]. More recent approaches incorporate fuzzy logic and deep reinforcement learning to enable more personalized and adaptable insulin dosing [2].

Table 2: Evolution of Control Algorithms in Artificial Pancreas Systems

| Algorithm Type | Core Mechanism | Advantages | Commercial Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) [2] | Adjusts delivery based on current glucose, glucose curve area, and rate of change [2] | Simple, responsive [2] | Medtronic MiniMed systems [1] |

| Model Predictive Control (MPC) [1] [2] | Uses mathematical modeling to predict future glucose trajectories [2] | Forecasting capability [2] | Tandem Control-IQ, CamAPS FX [1] |

| Fuzzy Logic [1] [2] | Codifies clinical decision-making for personalized dosing [2] | Adaptable to individual differences [1] | MiniMed 780G (added to PID) [1] |

| Adaptive Closed-Loop [6] | Initialized with body weight only; learns individual insulin needs over time [6] | Minimal user configuration required [6] | iLet Bionic Pancreas [6] |

Commercial System Landscape

Multiple commercial AP systems are now available, each with distinct control approaches and features:

Table 3: Commercial Artificial Pancreas Systems (2024-2025)

| Commercial System | Algorithm Type | Key Features | Target Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medtronic 780G [1] | PID + Fuzzy Logic [1] | Automatic basal rate and correction boluses [1] | Type 1 diabetes |

| Tandem t:slim X2/Mobi with Control-IQ [1] | MPC [1] | Automates basal rate and correction boluses [1] | Type 1 diabetes |

| Insulet OmniPod 5 [1] | MPC [1] | Tubeless patch pump [1] | Type 1 diabetes |

| Beta Bionics iLet [1] [6] | Adaptive Closed-Loop [6] | Weight-based initialization; meal estimation without carb counting [6] | Type 1 diabetes (ages 6+) |

| CamAPS FX [1] | MPC [1] | Mobile app; first approved for pregnant women with T1D [1] | Type 1 diabetes, including pregnancy |

| Inreda AP [1] | Dual-hormone (Insulin + Glucagon) [1] | Bi-hormonal fully automated system [1] | Type 1 diabetes (available overseas) |

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Clinical Validation Framework

The path from research to clinical adoption required rigorous validation frameworks. Early clinical trials focused on overnight control in supervised settings, gradually progressing to longer-term outpatient studies with increasing complexity [1] [8]. The following diagram illustrates a generalized clinical validation pathway for artificial pancreas systems:

Figure 2: Artificial Pancreas Clinical Validation Pathway. Systems progress through increasingly complex environments with corresponding evaluation metrics at each stage.

Standardized Outcome Metrics

Consensus has emerged around standardized metrics for evaluating AP system performance, moving beyond HbA1c alone to comprehensive continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) metrics [3]:

Table 4: Standardized Outcome Metrics for AP System Evaluation

| Metric Category | Specific Measures | Target Values |

|---|---|---|

| Hypoglycemia [3] | Time <70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L); Time <54 mg/dL (3.0 mmol/L); Seizure/loss of consciousness | Minimize |

| Time-in-Range [3] | 70-180 mg/dL (3.9-10.0 mmol/L); 70-140 mg/dL (3.9-7.8 mmol/L) | Maximize (>70%) |

| Hyperglycemia [3] | Time >180 mg/dL (10.0 mmol/L); Time >250 mg/dL (13.9 mmol/L); Diabetic ketoacidosis | Minimize |

| Overall Control [3] | Mean glucose; Glycemic variability (coefficient of variation) | Individualized |

| Data Sufficiency [3] | ≥70% of possible CGM readings over 2-week collection | Minimum standard |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

AP research requires specialized tools and platforms for development and testing:

Table 5: Essential Research Tools for Artificial Pancreas Development

| Research Tool | Function | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| University of Virginia/UCSB APS Platform [1] | Universal research platform enabling automated communication between CGMs, pumps, and algorithms [1] | Powered first inpatient clinical trials; enabled standardized testing [1] |

| FDA-Accepted T1D Simulator [1] | Computer simulator of human metabolic system in T1D [1] | Accepted by FDA as substitute for animal trials; accelerated development by years [1] |

| Diabetes Assistant [1] | Mobile-based platform using Android smartphone as computational hub [1] | Enabled portable outpatient studies with remote monitoring [1] |

| mGIPsim Python Simulator [7] | Software simulator for closed-loop control testing with meal and exercise scenarios [7] | Enables algorithm testing without clinical trials [7] |

| Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF) [7] | State estimation technique for real-time glucose prediction [7] | Enhances model predictive control accuracy [7] |

| Recursive Least Squares (RLS) [7] | Parameter estimation algorithm for adaptive control [7] | Enables personalization of system parameters [7] |

| Perphenazine sulfoxide | Perphenazine Sulfoxide | Perphenazine sulfoxide is a key metabolite of the antipsychotic perphenazine. This product is for research use only (RUO). Not for human use. |

| 2-Nitrobenzyl alcohol | 2-Nitrobenzyl alcohol, CAS:612-25-9, MF:C7H7NO3, MW:153.14 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The development of artificial pancreas systems from initial concept to standard of care represents a remarkable achievement in biomedical engineering and diabetes care. This journey, facilitated by strategic public and private partnerships, has transformed diabetes management through automated insulin delivery technology. Current systems have established a foundation of safety and efficacy across diverse populations, while next-generation innovations continue to refine personalization, adaptability, and user experience. Future directions include full closed-loop control without meal announcements, integration of additional hormones like glucagon, enhanced machine learning algorithms for personalized adaptation, and expansion to broader populations including those with type 2 diabetes [3] [7]. The historical progression documented in this application note provides both methodological guidance and conceptual framework for researchers continuing to advance the field of automated insulin delivery.

The artificial pancreas (AP), or automated insulin delivery (AID) system, represents a paradigm shift in the management of Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) [1]. This closed-loop system mimics the glucose-regulatory function of a healthy pancreas by integrating three core technological components: a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), an insulin pump, and a control algorithm [9] [10]. This document deconstructs the architecture of these systems, providing application notes and experimental protocols framed within research on AP closed-loop control system design.

Core Component Deconstruction

Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM)

The CGM serves as the system's sensor, providing real-time estimates of glucose levels in the interstitial fluid [11].

Operating Principle: A disposable sensor is inserted subcutaneously, where it measures glucose concentration in the interstitial fluid via an enzymatic reaction [11] [12]. A transmitter sends this data wirelessly to a receiver, which can be a dedicated device, a smartphone, or the insulin pump itself [11] [10]. It is critical to note an inherent physiological delay of approximately 10 minutes between blood glucose and interstitial fluid glucose readings, which the control algorithm must account for [12].

Key Performance Metrics: Accuracy is primarily quantified by the Mean Absolute Relative Difference (MARD), with a value below 10% considered acceptable for insulin dosing [12]. Recent technological advancements have pushed MARD values below 9% for leading systems [12].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Selected CGMs

| CGM Model | MARD (%) | Warm-up Time | Sensor Life (Days) | Calibration Required? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbott FreeStyle Libre 3 | 7.9 [12] | 1 hour [12] | 14 [12] | No [12] |

| Dexcom G7 | 8.2 [12] | 0.5 hours [12] | 10 [12] | No [12] |

| Medtronic Guardian 4 | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing |

Research Considerations: Factors such as sensor compression during sleep, prolonged aerobic exercise, and interfering substances (e.g., acetaminophen, ascorbic acid, hydroxyurea) can affect CGM accuracy and are active areas of investigation [11] [12].

Insulin Pump

The insulin pump functions as the system's actuator, delivering rapid-acting insulin analogs subcutaneously [13] [14].

Operating Principle: The pump mimics physiological insulin secretion by providing a continuous low basal rate (background insulin) and on-demand bolus doses (for meals or high glucose corrections) [13]. Pumps are classified as either tubed (tethered) or tubeless (patch pumps) [13]. In a closed-loop system, the pump receives dosing commands from the control algorithm.

Delivery Modes:

- Manual Mode: The user or clinician sets a predetermined basal rate [14].

- Auto Mode (Closed-Loop): The pump automatically modulates the basal insulin delivery based on CGM readings and the control algorithm's instructions [14]. Contemporary commercial systems are primarily hybrid closed-loop systems, which automate basal insulin but require user input for meal boluses [1] [15].

Research Considerations: A significant research challenge involves failures in insulin delivery, which can arise from bent or kinked cannulas, insulin crystallization in the infusion set, inflammation at the infusion site, or tubing issues, all of which can lead to hyperglycemia and diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) [13]. Safety features like Predictive Low Glucose Suspend (PLGS) are critical, halting insulin delivery up to 30 minutes before predicted hypoglycemia [14].

Control Algorithm

The control algorithm is the central processing unit of the AP, determining the required insulin dose based on CGM data and other inputs [1] [8].

Core Algorithm Types:

- Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID): Uses a predefined equation to calculate insulin delivery based on the error (difference between current and target glucose) and its integral and derivative [12] [16]. It often incorporates Insulin Feedback (IFB) to account for the suppressive effect of existing plasma insulin [12].

- Model Predictive Control (MPC): A more advanced method that uses a model of the patient's glucose-insulin dynamics to predict future glucose levels and preemptively calculate optimal insulin delivery over a defined "horizon" [1] [12]. This approach is particularly suited for systems with large time delays [12].

- Fuzzy Logic (FL): Mimics human decision-making under uncertainty, allowing the algorithm to respond to non-modeled disturbances such as unannounced meals, illness, or exercise [1] [12]. It is often used in conjunction with other algorithms.

Table 2: Algorithm Types in Commercial AID Systems

| Commercial System | Primary Algorithm | Additional Features |

|---|---|---|

| Medtronic MiniMed 780G | PID [12] | Integrated Fuzzy Logic for correction boluses [1] [12] |

| Tandem t:slim X2 with Control-IQ | MPC [1] [12] | Automates basal and correction boluses [1] |

| Insulet OmniPod 5 | MPC [1] [12] | |

| Beta Bionics iLet | MPC [1] [12] | |

| CamAPS FX | MPC [1] [12] |

Advanced Research Directions: Current research explores the use of multi-hormonal systems (e.g., co-delivery of insulin and glucagon) [12] [14], the integration of machine learning and AI for personalized predictive models [12] [9], and the application of ultra-rapid-acting insulin analogues to improve system responsiveness [12].

Experimental Protocols for System Validation

Robust clinical validation is essential for the translation of AP systems from research to clinical practice. The following protocols outline standardized methodologies.

Protocol 1: Inpatient Meal Challenge Study

Objective: To evaluate the performance and safety of an AID system in a controlled environment, with a specific focus on postprandial glucose control.

Methodology:

- Participant Selection: Recruit adults with T1D. Key exclusion criteria include hypoglycemia unawareness and recent severe hypoglycemic events.

- Study Setup: Conduct the trial in a clinical research unit. Insert the study CGM and connect the investigational insulin pump. For comparison, a control arm may use sensor-augmented pump (SAP) therapy.

- Meal Intervention: After an overnight fast and stabilization period, provide a standardized high-carbohydrate breakfast (e.g., 60-80g). The meal is announced to the system in hybrid closed-loop studies, and a user-initiated bolus is delivered.

- Data Collection: The primary outcome is the mean peak postprandial glucose level in the 3-4 hours following the meal [16]. Secondary outcomes include time-in-range (70-180 mg/dL), time in hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL), and time in hyperglycemia (>180 mg/dL).

- Analysis: Compare the postprandial glucose trajectories and key metrics between the AID and control groups.

Protocol 2: Outpatient Free-Living Pivotal Trial

Objective: To assess the long-term efficacy, safety, and usability of an AID system in a real-world setting.

Methodology:

- Study Design: A multicenter, randomized, controlled trial.

- Intervention: Participants are randomized to use either the investigational AID system or a control therapy (e.g., SAP) for a period of 3 to 6 months [1].

- Primary Endpoint: The change in HbA1c from baseline to the end of the study.

- Key Secondary Endpoints:

- Time-in-Range (TIR): The percentage of time with CGM values between 70 and 180 mg/dL [1].

- Hypoglycemia Exposure: The area under the curve (AUC) for time spent below 70 mg/dL and below 54 mg/dL.

- Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs): Measured using validated questionnaires on diabetes distress and quality of life.

- Data Analysis: Perform an intention-to-treat analysis to compare the changes in HbA1c and CGM-derived metrics between groups.

System Architecture and Validation Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: AP System Architecture & Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Artificial Pancreas Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in AP Research |

|---|---|

| University of Virginia (UVA)/Padova Simulator | A widely accepted computer simulator of the human metabolic system in T1D, accepted by the FDA as a substitute for animal trials in the preliminary testing of AID algorithms [1]. |

| Artificial Pancreas System (APS) | A universal research platform (e.g., from the University of California, Santa Barbara) that enables automated communication between various CGMs, pumps, and control algorithms, powering initial inpatient clinical trials [1]. |

| Continuous Glucose Monitors (e.g., Dexcom G6/G7, Abbott Libre 3) | Provide the continuous stream of glucose data necessary for algorithm operation. Different models offer varying MARD, warm-up times, and form factors for testing [12]. |

| Insulin Pumps (e.g., Tandem t:slim, Insulet OmniPod, Medtronic) | The mechanical actuators for insulin delivery. Research requires pumps with open or documented communication protocols to interface with research algorithms [1] [13]. |

| Rapid-Acting Insulin Analogues (e.g., Lispro, Aspart) | The standard insulin formulation used in pump therapy. Research is ongoing into ultra-rapid-acting analogues (e.g., Fiasp, Lyumjev) to improve system responsiveness [12] [14]. |

| Glucagon (Stable Formulation) | For research into bi-hormonal AP systems. Glucagon can be administered to counteract or prevent hypoglycemia, allowing for more aggressive insulin dosing [12] [16]. |

| Zinc sulfate monohydrate | Zinc Sulfate Monohydrate for Research Applications |

| 3,29-Dibenzoyl Rarounitriol | 3,29-Dibenzoyl Rarounitriol, MF:C44H58O5, MW:666.9 g/mol |

The pursuit of an Artificial Pancreas (AP) represents a paramount endeavor in diabetes management, aiming to restore automated, physiological glucose homeostasis in individuals with insulin deficiency [2] [17]. The core challenge lies in replicating the exquisite biological control of a healthy pancreas, which maintains blood glucose within a narrow range through complex, dynamic interactions between hormones and metabolic processes [18] [19]. This application note delineates the physiological and mathematical foundations of glucose-insulin dynamics, with a specific focus on the compelling rationale for pulsatile hormone delivery as a superior modality for closed-loop control systems. Framed within broader thesis research on AP design, this document provides a detailed analysis for researchers and scientists engaged in developing next-generation automated insulin delivery systems.

Physiological Basis of Glucose Homeostasis

In healthy physiology, glucose homeostasis is maintained by a tightly regulated balance between insulin and glucagon, secreted by pancreatic β-cells and α-cells, respectively [2]. This system operates as a closed-loop feedback mechanism where blood glucose concentration is the primary input and hormone secretion is the output.

- Insulin Physiology: Insulin is an anabolic hormone that promotes cellular glucose uptake, inhibits hepatic glucose production, and facilitates glycogen synthesis [20]. Its secretion occurs in two key patterns: a continuous basal secretion that maintains fasting glucose levels, and a rapid prandial secretion in response to meals [20].

- Glucagon Physiology: Glucagon acts as a counter-regulatory hormone, stimulating hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis to prevent hypoglycemia during fasting states [21].

- The Healthy Feedback Loop: Post-meal glucose elevation triggers insulin release, which suppresses glucagon and promotes glucose disposal. As glucose levels normalize, insulin secretion subsides. Conversely, a declining glucose level is countered by glucagon secretion, which stimulates endogenous glucose production [18] [2].

In Type 1 Diabetes (T1D), the autoimmune destruction of β-cells dismantles this feedback loop, necessitating exogenous insulin replacement [2]. Traditional therapy, whether via multiple daily injections or continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII), struggles to mimic the dynamic, responsive nature of endogenous secretion, leading to significant glycemic variability and an increased risk of both hyper- and hypoglycemia [2] [22].

Mathematical Modeling of Glucose-Insulin Dynamics

Mathematical models are indispensable tools for understanding glucose-insulin physiology and designing effective AP control algorithms. These models range from simple representations to complex, multi-compartmental descriptions of the system.

Table 1: Key Classes of Glucose-Insulin Models

| Model Class | Key Characteristics | Primary Application | Examples/References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal Models | Parsimonious structure; estimates SI (insulin sensitivity) and SG (glucose effectiveness). |

Analysis of Intravenous Glucose Tolerance Test (IVGTT) data. | Bergman's Minimal Model [18] [23] |

| Physiological Compartmental Models | Multi-compartment; represents glucose & insulin kinetics in specific body pools (e.g., plasma, interstitial, liver). | Control-oriented prediction for AP algorithms. | UVA/Padova Simulator [24] [1] |

| Control Algorithm Models | Tailored for real-time insulin dosing decisions; often include safety constraints. | Core of commercial and research AP systems. | Model Predictive Control (MPC), Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) [2] [17] [24] |

A control-oriented, physiological long-term model can be described by the following compartmental equations [24]:

Glucose Subsystem:

dG(t)/dt = Ra(t) + EGP(t) - Si * G(t) * I(t) - k * G(t)WhereG(t)is plasma glucose,Ra(t)is glucose rate of appearance from meals,EGP(t)is endogenous glucose production,Siis insulin sensitivity,I(t)is plasma insulin, andkis glucose effectiveness.Insulin Subsystem:

dI(t)/dt = (1/Vi) * [Y(t) - ke * I(t)]dY(t)/dt = u(t) - kb * Y(t)WhereY(t)is subcutaneous insulin,u(t)is the insulin infusion rate,Viis the insulin distribution volume, andke,kbare elimination rate constants.

These equations form the basis for in-silico simulation and testing of AP controllers, such as the accepted UVA/Padova T1D Simulator [24] [1].

Signaling Pathways in Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion

The mechanism by which a healthy pancreatic β-cell senses glucose and secretes insulin in a pulsatile manner involves an integrated oscillator system. The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways and their interactions that lead to pulsatile insulin secretion.

Diagram 1: Integrated oscillator model of pulsatile insulin secretion in pancreatic β-cells. The process begins with glucose uptake and metabolism, leading to ATP production. Elevated ATP closes KATP channels, causing membrane depolarization and Ca2+ influx, which triggers insulin exocytosis. Crucially, intrinsic metabolic oscillations (red dashed lines) and Ca2+ feedback on metabolic pathways (blue dashed line) create a coupled oscillator system that generates rhythmic pulses of insulin secretion with a typical period of ~5 minutes [19].

Rationale for Pulsatile Hormone Delivery

A key insight from physiology is that a healthy pancreas secretes insulin and glucagon in a pulsatile manner, with discrete secretory bursts occurring every 5-7 minutes [18] [19]. This stands in stark contrast to the continuous, zero-order hold (ZOH) infusion employed by many conventional insulin pumps. There is a growing body of evidence advocating for the adoption of pulsatile delivery in AP systems.

Physiological and Clinical Advantages

- Enhanced Hepatic Suppression: Pulsatile insulin delivery has been demonstrated to more effectively suppress hepatic glucose production compared to continuous infusion [24]. The liver, being the primary recipient of portal venous insulin, is exquisitely sensitive to the oscillatory signal.

- Improved Insulin Action: Studies suggest that the pulsatile pattern enhances insulin action at the target tissue level, potentially due to the prevention of receptor desensitization that can occur with constant exposure [19].

- Superior Postprandial Control: Simulation and experimental studies indicate that a pulsatile infusion scheme, particularly one that allows for "super-bolus" administration (increasing the meal bolus while temporarily suspending basal insulin), results in better control of postprandial glucose excursions, especially for meals with a high glycemic index [24].

- Mitigation of Delays: The subcutaneous (SC) route for insulin infusion introduces significant pharmacodynamic delays. Pulsatile, discrete micro-boluses align more naturally with the pancreas's native sampling strategy, which itself may have evolved to circumvent transport time effects and ensure stable feedback control [18].

Quantitative Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Profiles

Table 2: Pharmacokinetic Profiles of Rapid-Acting Insulin Analogs (Subcutaneous Administration)

| Insulin Type | Onset of Action | Peak Action | Duration of Action | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin Lispro | 5-15 minutes | 30-60 minutes | 3-4 hours | [20] |

| Insulin Aspart | 10-20 minutes | 40-50 minutes | 3-5 hours | [20] |

| Insulin Glulisine | 20 minutes | ~1 hour | 4 hours | [20] |

| Regular Human Insulin | ~30 minutes | 60-120 minutes | 6-8 hours | [20] |

The faster pharmacokinetic (PK) profiles of modern analogs are crucial for effective AP operation, but delays remain a challenge. Pulsatile delivery is a strategy to optimize the utilization of these existing insulin formulations.

Experimental Protocols for Pulsatile AP System Evaluation

This section outlines a detailed protocol for evaluating a pulsatile-model predictive control (pZMPC) based AP system using an accepted in-silico environment.

Protocol: In-Silico Evaluation of a Pulsatile Zone MPC

1. Objective: To validate the glycemic performance and stability of a pulsatile Zone MPC (pZMPC) algorithm in controlling blood glucose in a simulated T1D population under conditions of announced and unannounced meals.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Software: UVA/Padova T1D Metabolic Simulator (T1DMS) Academic Version [24].

- Virtual Cohort: 10 adult in-silico patients from the T1DMS.

- Control Algorithm: Pulsatile Zone MPC (pZMPC) code, implemented in a suitable programming environment (e.g., MATLAB, Python) [24].

- Meal Dataset: Standardized meal plan (e.g., 3 meals per day, with varying carbohydrate content).

3. Methodology:

1. Model Individualization: For each virtual patient, individualize the parameters of the long-term glucose-insulin prediction model within the pZMPC. This typically involves estimating patient-specific insulin sensitivity (Si) and glucose effectiveness (k) parameters [24].

2. Controller Tuning:

- Set the target glucose zone (Y_Tar) to a safe range, e.g., 80 - 140 mg/dL.

- Define the prediction horizon (N) and control horizon (M). Typical values are N = 6-10 steps and M = 2-3 steps (with 5-minute sampling, this equates to 30-50 min prediction).

- Configure input constraints: 0 ≤ u(t) ≤ u_max, where u_max is the maximum allowed insulin pulse.

- Configure state constraints, particularly Insulin-on-Board (IOB) limits to prevent "stacking" [24].

3. State Observer Setup: Implement and tune two augmented observers to handle plant-model mismatch:

- An Output Disturbance Observer (ODO) for general model uncertainty.

- An Input Disturbance Observer (IDO) specifically for unannounced meals [24].

4. Simulation Scenarios:

- Scenario A (Hybrid Closed-Loop): All meals are announced 15 minutes prior. The pZMPC uses this information.

- Scenario B (Unannounced Meals): Meals are not announced to the controller, relying solely on the IDO for compensation.

- Scenario C (Optimal Bolus Calculator): Test an event-triggered pZMPC that computes an optimal bolus upon meal announcement, emulating an optimal Functional Insulin Therapy (FIT) strategy [24].

5. Performance Metrics: Run 24-hour simulations for each scenario and calculate:

- Time-in-Range (TIR): Percentage of time glucose is between 70-180 mg/dL.

- Time in Hypoglycemia: <70 mg/dL.

- Time in Hyperglycemia: >180 mg/dL.

- Mean Glucose.

- Glycemic Risk Indices (e.g, LBGI, HBGI).

4. Data Analysis: Compare the performance metrics across the different scenarios. A robust pZMPC should maintain high TIR (>75%) and minimal hypoglycemia (<2%) across all scenarios, with Scenario B performance demonstrating the resilience of the observer design.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for AP Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| UVA/Padova T1D Simulator | A widely accepted platform for in-silico testing of AP algorithms without the need for animal trials. | FDA-accepted substitute for preclinical testing [24] [1]. |

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) | Provides real-time, interstitial glucose measurements for feedback control. | Dexcom G7, Abbott FreeStyle Libre 3 (MARD <9%) [2]. |

| Insulin Pumps | Delivers subcutaneous micro-boluses of rapid-acting insulin analogs. | Tandem t:slim X2, Insulet OmniPod 5, Medtronic 780G [2] [1]. |

| Rapid-Acting Insulin Analogs | The therapeutic agent with optimized PK/PD profiles for responsive control. | Insulin Aspart, Lispro, Glulisine [20]. |

| Control Algorithm Platform | A unified software environment to integrate CGM, pump, and control algorithm for clinical testing. | The Artificial Pancreas System (APS) / Diabetes Assistant [1]. |

| Glucagon & GLP-1 Analogs | For bi-hormonal AP systems to mitigate hypoglycemia; GLP-1 can delay gastric emptying and suppress glucagon. | Native Glucagon; GLP-1 derivatives (e.g., NN2211) [21] [23]. |

| 5'-O-DMT-2'-TBDMS-Uridine | 5'-O-DMT-2'-TBDMS-Uridine, CAS:81246-80-2, MF:C36H44N2O8Si, MW:660.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 16-Acetoxy-7-O-acetylhorminone | 16-Acetoxy-7-O-acetylhorminone |

The transition from conceptual models to practical AP systems hinges on a deep appreciation of underlying physiology. Modeling glucose-insulin dynamics provides the predictive framework necessary for automation, while embracing the pulsatile nature of endogenous hormone delivery offers a path to more physiological, stable, and effective closed-loop control. The experimental protocols and research tools outlined herein provide a foundation for advancing the development of next-generation AP systems that more closely mimic the elegant biological intelligence of the healthy pancreas. Future work will focus on the integration of ultra-rapid insulin analogs, dual-hormone control, and adaptive learning algorithms to further narrow the performance gap between artificial and biological systems.

The evolution of Artificial Pancreas (AP) systems, also known as closed-loop or automated insulin delivery (AID) systems, represents a paradigm shift in the management of diabetes. The primary control objective for any AP system is to automate the maintenance of glucose homeostasis, mimicking the function of a healthy pancreas. The performance of these systems is quantitatively assessed using a set of standardized, complementary metrics that provide a holistic picture beyond traditional measures like HbA1c. Among these, Time-in-Range (TIR) and the minimization of hypoglycemia have emerged as the most critical endpoints for evaluating the safety and efficacy of closed-loop control algorithms in both research and clinical practice. This document outlines the key metrics, experimental protocols, and methodological tools essential for AP system design research.

The development of AP systems has transitioned from a disputed idea in 2005 to the gold-standard treatment for type 1 diabetes today [1]. Early systems focused on overnight glucose control to mitigate the risks of nocturnal hypoglycemia, but modern hybrid and fully closed-loop systems now aim for 24/7 glycemic control. This evolution has been powered by advances in continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), insulin pump technology, and sophisticated control algorithms such as Model Predictive Control (MPC) and Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) control [1]. The validation of these systems relies on a framework of CGM-derived metrics that capture the dynamic, complex nature of glucose physiology, with TIR serving as a primary outcome in pivotal clinical trials [25] [1].

Core Glycemic Metrics and Their Clinical Significance

Definition of Key Metrics

Glycemic metrics derived from CGM data provide a multi-dimensional view of glucose control. The international consensus recommendations have standardized the following core metrics for clinical trials and practice [26] [27]:

- Time-in-Range (TIR): Defined as the percentage of time that glucose levels are within the target range of 70-180 mg/dL (3.9-10.0 mmol/L). For most adults with diabetes, the target is >70% of daily readings (~17 hours per day) [28] [29] [26]. TIR is strongly correlated with a reduced risk of microvascular complications and is considered a primary efficacy endpoint for AP systems.

- Time Below Range (TBR): Categorized into two levels: Level 1 (<70 mg/dL or <3.9 mmol/L) and the more clinically significant Level 2 (<54 mg/dL or <3.0 mmol/L). Targets are <4% and <1% of the day, respectively [26] [27]. Minimizing TBR is the foremost safety objective in AP design, as hypoglycemia carries acute risks, including cognitive impairment and seizures [30].

- Time Above Range (TAR): Also categorized into two levels: Level 1 (>180 mg/dL or >10.0 mmol/L) and Level 2 (>250 mg/dL or >13.9 mmol/L). Targets are <25% and <5% of the day, respectively [26]. Elevated TAR indicates insufficient insulin delivery.

- Glycemic Variability (GV): Measured by the Coefficient of Variation (CV), calculated as (standard deviation / mean glucose) × 100. A CV of ≤36% is the target, indicating stable glucose levels with minimal fluctuations [26] [27]. High GV is an independent risk factor for hypoglycemia.

Table 1: Standardized Targets for Core Glycemic Metrics in Adults with Type 1 or Type 2 Diabetes

| Metric | Definition | Target (for most adults) | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-in-Range (TIR) | % of time in 70–180 mg/dL | ≥ 70% | Primary efficacy endpoint; predicts complication risk [26] |

| Time Below Range (TBR) Level 1 | % of time < 70 mg/dL | < 4% | Non-clinically significant hypoglycemia [26] |

| Time Below Range (TBR) Level 2 | % of time < 54 mg/dL | < 1% | Clinically significant hypoglycemia; key safety metric [26] [30] |

| Time Above Range (TAR) Level 1 | % of time > 180 mg/dL | < 25% | Hyperglycemia burden [26] |

| Time Above Range (TAR) Level 2 | % of time > 250 mg/dL | < 5% | Severe hyperglycemia [26] |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | (SD / Mean Glucose) × 100 | ≤ 36% | Measure of glycemic stability; predictor of hypoglycemia risk [26] [27] |

The Relationship Between TIR, Hypoglycemia, and A1C

While HbA1c has been the gold standard for decades, it represents a long-term average and cannot reveal acute glycemic excursions, hypoglycemia, or glucose variability [27]. CGM metrics like TIR provide a more dynamic and detailed picture. Research shows a strong inverse correlation between TIR and HbA1c; a higher TIR is generally associated with a lower HbA1c [28]. However, two patients with the same HbA1c can have vastly different TIR and hypoglycemia profiles, underscoring the necessity of these complementary metrics for a complete assessment [28] [27].

For AP systems, the minimization of hypoglycemia (TBR) is paramount. Hypoglycemia, particularly severe hypoglycemia, is associated with acute risks like seizures and coma, and in young children, it can lead to permanent cognitive impairment and brain-structural abnormalities [30]. Furthermore, hypoglycemia can induce hypoglycemia unawareness, creating a vicious cycle of recurrent events [30]. Therefore, a successful AP system must not only maximize TIR but do so while rigorously minimizing TBR.

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating AP System Performance

Protocol for a Nocturnal Glycemic Control Study

The overnight period is critical for testing AP systems due to the high risk of prolonged, unrecognized hypoglycemia and attenuated counterregulatory hormone responses [25] [30]. The following protocol is adapted from a pivotal study on Predictive Hyperglycemia and Hypoglycemia Minimization (PHHM) [25].

Objective: To determine the safety, feasibility, and efficacy of a PHHM system compared with a predictive low-glucose suspend (PLGS) system in overnight glucose control.

Primary Endpoint: The percentage of time spent in a sensor glucose range of 70–180 mg/dL during the overnight period [25].

Secondary Endpoints:

- Mean overnight and morning blood glucose concentration.

- Percentage of time in hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL and <54 mg/dL).

- Percentage of time in hyperglycemia (>180 mg/dL).

- Number of hypoglycemic events.

- Safety endpoints: episodes of severe hypoglycemia or diabetic ketoacidosis.

Methodology:

- Study Population: Recruit individuals with type 1 diabetes (e.g., aged 15-45 years) on insulin pump therapy. Exclude those with recent severe hypoglycemia or diabetic ketoacidosis.

- Run-in Phase: Participants use a CGM and insulin pump for 14-21 days to establish baseline metrics and familiarize themselves with the system.

- Randomization & Blinding: Participants are randomly assigned each night to either the experimental (PHHM) or control (PLGS) system. The assignment is blinded to the participant.

- Intervention:

- PHHM Nights: The system suspends basal insulin for predicted hypoglycemia and delivers automated correction boluses for predicted hyperglycemia.

- PLGS Nights: The system only suspends basal insulin for predicted hypoglycemia.

- Data Collection: The system is initiated at bedtime and deactivated upon waking. Overnight CGM data is collected. A capillary blood glucose measurement is taken upon waking.

- Statistical Analysis: Analyze data based on intention-to-treat. Compare primary and secondary endpoints between PHHM and PLGS nights using paired statistical tests (e.g., paired t-test). A sample size of 30 participants provides 90% power to detect a 5% difference in TIR [25].

In Silico Simulation Protocol for Control Algorithm Testing

Before human trials, control algorithms must be rigorously tested in simulation. The FDA-accepted University of Virginia/Padova Type 1 Diabetes Simulator is a critical tool for this purpose [1].

Objective: To validate a new control algorithm for an AP system using a computer-simulated cohort of virtual patients.

Primary Endpoint: Overall TIR (70-180 mg/dL) across the virtual cohort over a 7-day simulation period.

Methodology:

- Simulation Environment: Implement the control algorithm in a software environment that can interface with the T1D simulator (e.g., the Artificial Pancreas System (APS) platform [1]).

- Virtual Cohort: Select a representative cohort of virtual subjects (e.g., adults, adolescents, children) from the simulator's population.

- Simulation Scenarios:

- Nominal Conditions: Simulate standard daily living with standardized meal challenges.

- Perturbation Conditions: Introduce real-world challenges such as missed meal announcements, incorrect carbohydrate counting, and sensor/pump noise or dropouts.

- Data Analysis: Extract CGM traces and calculate all core glycemic metrics (TIR, TBR, TAR, CV, mean glucose) for each virtual subject and for the cohort overall.

- Algorithm Refinement: Use the results to iteratively refine and tune the control algorithm to optimize TIR and minimize TBR before proceeding to clinical trials.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for AP System Research & Development

| Category / Item | Specification / Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) | Enhanced Enlite (Medtronic) [25] / Commercial CGMs | Provides real-time, interstitial glucose measurements for feedback control. Accuracy and reliability are paramount. |

| Insulin Pump | MiniMed Paradigm Veo [25] / T:slim X2 [1] | Subcutaneous delivery of insulin. Must be capable of receiving automated commands from the controller. |

| Control Algorithm | Model Predictive Control (MPC) [1], PID, Fuzzy Logic [1] | The "brain" of the AP. Calculates optimal insulin doses based on CGM data, predictions, and meal information. |

| Research Platform | Artificial Pancreas System (APS) [1], Diabetes Assistant [1] | A unified software/hardware platform (often laptop or smartphone-based) to integrate CGM, pump, and algorithm for research. |

| In Silico Simulator | FDA-Accepted T1D Simulator (UVA/Padova) [1] | Provides a virtual patient cohort for safe, efficient, and reproducible initial testing and tuning of control algorithms. |

| Bi-hormonal System | Glucagon (e.g., INREDA AP [18]) | Utilized in advanced systems to mitigate hypoglycemia risk by administering glucagon as a counter-regulatory agent. |

| Zuclopenthixol Decanoate | Zuclopenthixol Decanoate | Zuclopenthixol decanoate is a long-acting antipsychotic reagent for neuroscience research. This product is for research use only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Cardiogenol C hydrochloride | Cardiogenol C Hydrochloride |

Advanced Concepts: Time-in-Tight-Range and Future Directions

As AP technology advances, enabling tighter glycemic control, the metric of Time-in-Tight-Range (TITR) is gaining attention. TITR is defined as the percentage of time spent in a narrower target range of 3.9-7.8 mmol/L (70-140 mg/dL) [31]. While highly correlated with TIR, TITR is a more sensitive indicator of optimal glucose control, particularly in situations where glucose levels are close to normal or when stricter targets are required, such as in pregnancy [31]. The rise of advanced hybrid closed-loop systems and new hypoglycemic drugs is making the achievement of high TITR a more feasible goal, positioning it as a future key metric for evaluating the performance of next-generation AP systems.

Future research will also focus on fully closed-loop systems that require no meal announcements, the integration of ultra-rapid insulin analogs to improve postprandial control, and the expansion of AP use to broader populations, including pregnant women and people with type 2 diabetes [1]. The standardization of core glycemic metrics, as detailed in this document, provides the essential framework for objectively assessing these innovations and driving the field forward.

The development of Artificial Pancreas (AP) systems represents a paradigm shift in the management of Type 1 Diabetes (T1D), transitioning from reactive insulin administration to automated, closed-loop glucose regulation. This evolution has been critically dependent on the creation and regulatory acceptance of high-fidelity metabolic simulators. These tools have fundamentally altered the development pipeline for diabetes technology, serving as a bridge between conceptual algorithm design and clinical implementation. The University of Virginia/Padova (UVA/Padova) T1D Simulator, accepted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2008 as a substitute for animal trials in the preclinical testing of insulin treatment strategies, marked an unprecedented milestone that accelerated the entire field [32] [33]. This document details the regulatory framework, simulator architecture, and experimental protocols that underpin modern AP development, providing researchers with a roadmap for leveraging these accepted tools to streamline the path to FDA clearance.

The Regulatory Paradigm Shift: From Animal Trials to In Silico Testing

The preclinical assessment of Automated Insulin Delivery (AID) systems historically relied on animal studies, a process that was both time-consuming and limited in its ability to represent human metabolic variability. A pivotal change occurred in 2008 when the FDA accepted the UVA/Padova T1D Simulator as a valid alternative to animal trials for the preclinical testing of insulin treatment strategies and control algorithms [32] [1]. This decision was based on the simulator's sophisticated representation of glucose-insulin dynamics and its incorporation of observed inter-individual variability across a population of virtual subjects.

This regulatory shift enabled rapid, cost-effective, and extensive testing of new treatment approaches. The simulator allows researchers to evaluate algorithm performance and safety across a wide spectrum of metabolic phenotypes and challenging scenarios before ever initiating human trials. This in silico testing framework has become a cornerstone of the AP development process, compressing development timelines and providing a robust platform for iterative algorithm refinement [33]. The acceptance of this simulator, and subsequently others, established a new precedent for the role of computational modeling in the regulatory approval of medical devices.

Table 1: Key Milestones in the Regulatory Acceptance of Metabolic Simulators for AP Development

| Year | Milestone | Impact on AP Development |

|---|---|---|

| 2008 | FDA acceptance of the UVA/Padova T1D Simulator as a substitute for animal trials [33] | Enabled faster, cheaper, and more extensive preclinical algorithm testing. |

| Pre-2008 | Preclinical testing relied on animal studies [33] | Slower development cycles and limited representation of human metabolic variability. |

| 2016 Onwards | FDA clearance of commercial hybrid closed-loop systems (e.g., Medtronic 670G) that leveraged in silico testing [1] | Established a clear pathway from simulator-validated algorithms to commercially approved devices. |

| Recent Years | FDA acceptance of CGM metrics (Time in Range, etc.) as complementary outcome measures to HbA1c [3] | Aligned regulatory endpoints with the rich data outputs generated by simulators. |

Architecture and Validation of Accepted Metabolic Simulators

The UVA/Padova T1D Simulator: A Benchmark Platform

The UVA/Padova T1D Simulator is a large-scale, physiologically-based mathematical model of the human metabolic system. Its development was underpinned by extensive phenotypic data from studies in over 200 adults and children, which utilized the triple tracer technique to derive key metabolic indices and parameters [32] [33]. This methodology provided robust, model-independent estimates of fundamental glucose fluxes, including endogenous glucose production (EGP), whole-body glucose disappearance (Rd), and the systemic appearance rate of meal carbohydrates (MRa).

The simulator's core model is described by a system of differential equations that capture the essential dynamics of glucose regulation. Key features of its architecture include:

- Comprehensive Representation: The model includes sub-models for subcutaneous insulin kinetics, glucose absorption from the gut, insulin action on glucose production and disposal, and glucose-renal excretion [33].

- Virtual Population: The simulator incorporates a population of N=300 in silico "subjects" (100 adults, 100 adolescents, and 100 children) with T1D. These virtual subjects are generated from the joint multivariate probability distribution of model parameters, ensuring they reflect the inter-individual variability observed in the real T1D population [33].

- Integrated Device Models: It includes models of continuous glucose monitors (CGM) and insulin pumps, enabling closed-loop simulation that accounts for the real-world performance characteristics of these devices [33].

Key Model Parameters and Inputs

The simulator requires specific inputs to function and generates outputs that are critical for algorithm assessment.

Table 2: Core Inputs and Outputs of a Metabolic Simulator for AP Testing

| Category | Parameter/Component | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Inputs | Meal Carbohydrate Content | The amount and timing of carbohydrate intake, a major disturbance to the system. |

| Basal Insulin Profile | The underlying (open-loop) basal insulin delivery rate. | |

| Controller Algorithm | The external control algorithm that determines insulin dosing based on CGM readings. | |

| Model Parameters | Insulin Sensitivity (SI) | A key parameter governing the effect of insulin on glucose disposal and production [32]. |

| Glucose Effectiveness (SG) | The ability of glucose itself to promote its own disposal and suppress endogenous production [32]. | |

| Carb Absorption Time Constants | Individual-specific parameters governing the rate of glucose appearance from the gut [33]. | |

| Outputs | Glucose Trajectory | The primary outcome, a time-series of blood glucose concentrations. |

| Insulin Delivery Profile | A time-series of insulin doses commanded by the control algorithm. | |

| CGM Readings | Simulated interstitial glucose readings, including sensor noise. | |

| Performance Metrics | Time in Range (TIR) | Percentage of time glucose is between 70-180 mg/dL [3]. |

| Time in Hypoglycemia | Percentage of time glucose is <70 mg/dL and <54 mg/dL [3]. | |

| Glycemic Variability (CV) | Coefficient of variation, a measure of glucose swings [3]. |

Diagram 1: Closed-loop simulation workflow. The controller algorithm processes CGM values to command insulin doses, which the virtual patient model responds to, creating a feedback loop. Performance is evaluated against standard metrics.

Experimental Protocols for In Silico Evaluation of AID Systems

The following protocols provide a standardized methodology for using accepted simulators in the preclinical evaluation of AP algorithms.

Protocol: Assessing Basal Control and Overnight Performance

1. Objective: To evaluate the ability of the control algorithm to maintain glucose levels in a target range during the fasting state, particularly overnight, and to assess its robustness to variations in basal insulin needs. 2. Virtual Subjects: A cohort of at least 10 adult in silico subjects from the accepted simulator population. 3. Simulation Setup:

- Duration: 24-hour simulation.

- Meals: No meal intake. This isolates the algorithm's basal control performance.

- Initial Conditions: Start each virtual subject at a different initial glucose level (e.g., 90 mg/dL, 120 mg/dL, 150 mg/dL) to test convergence to target.

- Controller: Implement the candidate control algorithm with standard settings. 4. Data Collection & Analysis:

- Record glucose traces and insulin delivery profiles.

- Calculate key performance metrics: Time in Range (70-180 mg/dL), Time Below Range (<70 mg/dL), Mean Glucose, and Glycemic Variability (CV) for the entire 24-hour period and specifically for the overnight period (e.g., 00:00 - 06:00) [3].

- Success Criterion: >95% time in range (70-180 mg/dL) and 0% time <70 mg/dL during the overnight period.

Protocol: Evaluating Meal Challenge Response

1. Objective: To test the algorithm's ability to mitigate postprandial hyperglycemia following a standardized meal without causing late-postprandial hypoglycemia. 2. Virtual Subjects: The same cohort as in Protocol 4.1. 3. Simulation Setup:

- Duration: 6-hour simulation post-meal.

- Meal: A standardized meal (e.g., 50g of carbohydrates) announced to the algorithm at time t=0. For fully closed-loop testing, the meal may be unannounced.

- Initial Conditions: Start each virtual subject at a euglycemic level (~110 mg/dL) to ensure a consistent baseline. 4. Data Collection & Analysis:

- Record glucose traces and insulin delivery profiles.

- Calculate the postprandial glucose peak, time to peak, and time to return to target range.

- Calculate TIR and Time Below Range for the 6-hour period.

- Success Criterion: Peak postprandial glucose <180 mg/dL and >0% time <70 mg/dL during the 6-hour post-meal period.

Protocol: Robustness Testing with Inter-Subject Variability

1. Objective: To validate algorithm performance and safety across the entire spectrum of the virtual population, capturing extreme but plausible metabolic phenotypes. 2. Virtual Subjects: The entire available in silico population (e.g., 100 adults, 100 adolescents, 100 children). 3. Simulation Setup:

- Duration: 3-day simulation with a standardized meal plan (e.g., three 50g carbohydrate meals per day).

- Scenarios: Include variations such as missed meal boluses (for hybrid systems) or unannounced snacks to test robustness. 4. Data Collection & Analysis:

- Aggregate performance metrics (TIR, TBR, Mean Glucose, CV) across the entire population.

- Identify the "worst-case" virtual subjects who experience the most hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia.

- Success Criterion: Population median TIR >70% and percentage of subjects experiencing any severe hypoglycemia (<54 mg/dL) for >1% of the time is <5% [3].

Table 3: Summary of Key Experimental Protocols for In Silico AP Evaluation

| Protocol | Primary Objective | Key Performance Metrics | Success Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basal Control | Evaluate fasting-state glucose control, especially overnight. | Overnight TIR, Hypoglycemia (%) | >95% TIR, 0% hypoglycemia overnight. |

| Meal Challenge | Assess postprandial glucose control after a standardized meal. | Postprandial peak, Time in Range after meal. | Peak <180 mg/dL, no significant hypoglycemia. |

| Robustness Testing | Validate safety and efficacy across a broad virtual population. | Population median TIR, % of subjects with hypoglycemia. | Median TIR >70%, <5% of subjects with significant hypoglycemia. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following tools and components are essential for conducting rigorous in silico research and development of AP systems.

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for AP Development

| Tool / Component | Function in Research | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Accepted T1D Simulator | The core platform for preclinical in silico trials and algorithm testing. | UVA/Padova T1D Simulator (accepted by FDA) [32] [33]. |

| Control Algorithm Design Software | Environment for developing and prototyping control strategies. | MATLAB/Simulink, Python (with SciPy, TensorFlow for AI approaches [34]). |

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) Model | Simulates the real-world performance of CGMs, including noise and delays. | Integrated into simulators; key parameter is MARD (Mean Absolute Relative Difference) [33]. |

| Insulin Pump Model | Simulates the delivery mechanism and pharmacokinetics of subcutaneous insulin. | Integrated into simulators; models rapid-acting insulin analogs [33]. |

| Virtual Patient Population | A cohort of in silico subjects with T1D representing inter-individual variability. | Included in the UVA/Padova simulator (n=300 across adults, adolescents, children) [33]. |

| Performance Metric Calculator | Software to compute standardized glycemic metrics from simulation outputs. | Calculates Time in Range, hypoglycemia metrics, GV, etc., as per consensus guidelines [3]. |

| Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) Framework | For developing data-driven, adaptive control algorithms. | Used in research for fully closed-loop systems; e.g., Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithms [34]. |

| 2-Geranyl-4-isobutyrylphloroglucinol | 2-Geranyl-4-isobutyrylphloroglucinol, MF:C20H28O4, MW:332.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 5,6-Dimethoxy-2-isopropenylbenzofuran | 5,6-Dimethoxy-2-isopropenylbenzofuran, MF:C13H14O3, MW:218.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Diagram 2: The role of simulators in the AP development pipeline. In silico testing creates a iterative loop with algorithm design, generating the data needed for regulatory approval to begin clinical trials.

The regulatory and simulator landscape for Artificial Pancreas systems has matured into a sophisticated framework that efficiently translates engineering innovation into clinical reality. The acceptance of metabolic simulators like the UVA/Padova model has not only accelerated development but has also enhanced the safety profile of new AID systems by enabling exhaustive preclinical testing across a diverse virtual population. For researchers, a deep understanding of this landscape—including the architecture of accepted simulators, standardized experimental protocols, and the essential research toolkit—is no longer optional but fundamental to the successful development and regulatory clearance of the next generation of automated insulin delivery technologies.

Algorithmic Core: A Deep Dive into Control Strategies and Emerging AI Paradigms

Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) and Model Predictive Control (MPC) represent two fundamental approaches to feedback control with significant implications for safety-critical systems. While PID control has dominated industrial applications for decades due to its simplicity and reliability, MPC has emerged as a sophisticated alternative capable of handling complex constraints and predicting future system behavior. This comparative analysis examines these control paradigms within the context of commercial systems, with particular relevance to closed-loop artificial pancreas (AP) design. Understanding their operational principles, implementation requirements, and performance characteristics provides crucial insights for researchers and drug development professionals working on automated drug delivery systems.

The development of an artificial pancreas represents one of the most challenging control problems in biomedical engineering, requiring precise glucose regulation despite numerous disturbances including meals, physical activity, stress, and physiological variations. This application note analyzes how established control algorithms from industrial applications can inform AP closed-loop control system design, highlighting methodological considerations for preclinical testing and implementation.

Theoretical Foundations and Comparative Analysis

PID Control: Principles and Characteristics

The PID controller is a feedback mechanism that continuously calculates an error value ( e(t) ) as the difference between a desired setpoint and a measured process variable, applying a correction based on proportional, integral, and derivative terms [35] [36]. The mathematical representation of the PID algorithm is:

[ u(t) = Kp e(t) + Ki \int e(t)dt + K_d \frac{de(t)}{dt} ]

where ( u(t) ) is the control signal, ( e(t) ) is the error, and ( Kp ), ( Ki ), and ( K_d ) are the proportional, integral, and derivative gains, respectively [37]. Each component addresses a different aspect of the system response: the proportional term reacts to the present error, the integral term eliminates steady-state offset by accumulating past errors, and the derivative term anticipates future trends based on the rate of error change [36].

PID controllers excel in applications with well-defined dynamics where precise modeling is challenging [35]. Their widespread adoption in industrial settings (over 80% of process control loops) stems from straightforward implementation, reliability, and well-established tuning methodologies [38]. The algorithm's simplicity enables computationally efficient execution on low-power microcontrollers, making it suitable for embedded medical devices with limited processing capabilities [36].

MPC: Principles and Characteristics

Model Predictive Control is an advanced control strategy that employs an explicit dynamic model of the process to predict future system behavior over a finite horizon [39]. At each control interval, MPC solves a constrained optimization problem to determine a sequence of control actions that minimizes a cost function, typically implementing only the first step before repeating the process [39]. This receding horizon approach enables anticipatory control actions based on predictions of future disturbances and system states.

The core components of MPC include [35]:

- Process Model: A mathematical representation (linear or nonlinear) of system dynamics

- Cost Function: An objective function (often quadratic) quantifying control performance

- Optimization Algorithm: Computational method for minimizing the cost function subject to constraints

MPC's distinctive capability to handle multi-variable systems with constraints on both inputs and outputs makes it particularly valuable for complex processes [39] [40]. By anticipating future events and proactively adjusting control actions, MPC can achieve performance superior to reactive approaches like PID, especially for systems with significant time delays or complex dynamics [39].

Comparative Analysis: PID vs. MPC

Table 1: Comparative analysis of PID and MPC control algorithms

| Characteristic | PID Control | Model Predictive Control |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Error-based feedback [35] | Model-based optimization [35] |

| Model Requirement | Not required [40] | Essential (white-box, gray-box, or black-box) [41] |

| Constraint Handling | Limited (requires modifications) [35] | Explicit (directly incorporated in optimization) [39] [40] |

| Predictive Capability | None (reactive only) [39] | Explicit prediction horizon [35] [39] |

| Computational Demand | Low [35] | High (solving optimization at each step) [35] [41] |

| Multi-variable Control | Decoupled loops required [35] | Native multi-variable capability [39] |

| Implementation Complexity | Low [35] | High (requires modeling and optimization) [35] [41] |

| Typical Applications | Temperature, pressure, flow control [35] [38]; HVAC [40] | Chemical processes [35]; building energy management [42] [41]; automotive systems [35] |

Table 2: Performance characteristics in representative applications

| Performance Metric | PID Control | Model Predictive Control |

|---|---|---|

| Setpoint Tracking | Good for simple dynamics [35] | Superior for complex dynamics [35] [40] |

| Disturbance Rejection | Reactive only [39] | Proactive (anticipates disturbances) [35] [40] |

| Time Delay Handling | Performs poorly without modifications [35] | Excellent (explicitly accounts for delays) [35] [40] |

| Energy Efficiency | Moderate [40] | Superior (10-30% improvement in building HVAC) [42] [40] |

| Implementation Scale | Component-level control [35] | System-wide optimization [41] |

The fundamental distinction between these approaches lies in their operational philosophy: PID is reactive, responding to past and present errors, while MPC is proactive, using predictions to optimize future performance [39] [40]. This distinction has significant implications for applications like artificial pancreas systems where meal anticipation and circadian variations create predictable disturbances.

Diagram 1: Architectural comparison of PID and MPC control systems

Applications in Commercial Systems

PID Control Applications

PID controllers maintain a dominant position in industrial automation due to their reliability and simplicity, with an estimated 80% of process control loops utilizing this technology [38]. Their implementation spans numerous sectors:

Temperature Regulation: PID controllers provide precise thermal management in pharmaceutical manufacturing, food processing, and HVAC systems, maintaining setpoints with minimal steady-state error [35] [38]. In commercial buildings, conventional thermostats often employ PID logic to adjust heating and cooling equipment based on temperature deviations [40].

Pressure and Flow Control: In oil and gas refineries, PID controllers stabilize pipeline pressure despite fluctuating inputs, enhancing safety and efficiency [38]. Water treatment facilities utilize PID algorithms to maintain steady flow rates for optimal filtration and chemical dosing, achieving energy reductions up to 10% [38].

Motion Control: Robotics and automation systems deploy PID controllers for precise positioning and velocity control of motors and servos, correcting mechanical drift and timing lag dynamically [43] [36].

The continued prevalence of PID control stems from its straightforward implementation on platforms ranging from simple analog circuits to modern microcontrollers, with extensive documentation and familiarity among engineers [36].

MPC Applications

MPC has gained significant traction in applications where complex dynamics, constraints, or economic objectives make simple feedback control inadequate:

Building Climate Control: MPC implementations in commercial HVAC systems demonstrate 10-30% energy savings compared to conventional control while maintaining or improving thermal comfort [42] [41]. By incorporating weather forecasts, occupancy patterns, and thermal mass dynamics, MPC optimizes building operation across multiple timescales [42] [44].

Chemical Process Industries: Since the 1980s, MPC has been widely deployed in chemical plants and refineries where multi-variable interactions and constraints are significant [39]. These implementations typically use linear empirical models obtained through system identification to handle complex process dynamics [39].

Automotive Systems: Vehicle control applications utilize MPC for tasks such as optimized fuel consumption and trajectory following, leveraging its ability to handle constraints and predict future system states [35] [39].

The growing adoption of MPC in recent years reflects advances in computing hardware, optimization algorithms, and system identification techniques that make implementation more feasible [42] [41].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: PID Controller Implementation and Tuning

Objective: Implement and tune a PID controller for precise regulation of a process variable.

Materials and Equipment:

- Process/simulation testbed (e.g., temperature chamber, glucose-insulin simulator)

- Sensors for process variable measurement (e.g., CGM for glucose monitoring)

- Actuator (e.g., infusion pump for insulin delivery)

- Microcontroller/PLC with PID implementation capability

- Data acquisition system

Procedure:

- System Identification:

- Apply step changes to the process input and record output response

- Determine key process parameters: gain (K), time constant (τ), dead time (θ)

- Calculate initial PID parameters using Ziegler-Nichols or Cohen-Coon methods [43]

Controller Implementation:

- Program PID algorithm on selected hardware platform

- Implement anti-windup protection for integral term

- Configure derivative filtering to reduce measurement noise sensitivity

Closed-Loop Tuning:

- Begin with conservative gains (approximately 50% of calculated values)

- Increase proportional gain until sustained oscillations occur

- Adjust integral time to eliminate steady-state error without excessive overshoot

- Add derivative action to dampen oscillations and improve settling time

- Fine-tune parameters to achieve quarter-wave decay ratio or specified performance metrics

Performance Validation:

- Test controller response to setpoint changes and disturbances

- Quantify performance metrics: rise time, settling time, overshoot, steady-state error

- Verify robustness under varying operating conditions

Troubleshooting:

- Excessive oscillation: Reduce proportional gain or increase derivative time

- Slow response: Increase proportional gain or reduce integral time

- Steady-state error: Reduce integral time

- Actuator saturation: Implement anti-windup strategy

Protocol 2: MPC Implementation for Constrained Systems

Objective: Design, implement, and validate a Model Predictive Controller for a system with constraints and measurable disturbances.

Materials and Equipment:

- Process/simulation testbed with constraint specifications

- Sensors for state estimation and disturbance measurement

- Computing platform capable of solving optimization problems in real-time

- Software tools for system identification and optimization (e.g., MATLAB, Python)

Procedure:

- Model Development:

- Collect input-output data from process under various operating conditions

- Identify model structure (transfer function, state-space, or neural network)

- Estimate model parameters using prediction error or subspace methods

- Validate model accuracy with separate dataset (minimum 70% fit)

Controller Formulation:

- Define prediction horizon (N) and control horizon (N_u)

- Formulate cost function incorporating tracking error and control effort

- Specify constraints on inputs, outputs, and states

- Select optimization algorithm (QP, SQP, or interior-point)

Implementation:

- Code optimization routine with efficient constraint handling

- Implement state estimator (Kalman filter) if not all states are measurable

- Develop disturbance models for measurable disturbances

- Establish real-time execution framework with fixed sampling period

Validation and Tuning:

- Test nominal performance with setpoint changes and disturbance rejection

- Verify constraint handling under extreme conditions

- Evaluate robustness to model mismatch and measurement noise

- Tune weighting matrices to achieve desired performance trade-offs

Performance Metrics:

- Constraint violation frequency and magnitude

- Computational time relative to sampling period

- Integrated absolute error (IAE) and control effort

- Stability under worst-case conditions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research tools for control system implementation

| Tool/Category | Representative Examples | Function/Application | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microcontrollers | TI MSP430FR2355 [36], STM32G0B1 [36], ATSAMD21G18 [36] | Embedded PID implementation | Low-power operation with analog peripherals |

| Processing Platforms | TMS320F280039C [36] | High-speed MPC implementation | Real-time digital signal processor for optimization |

| System Identification | MATLAB System ID Toolbox, Python SciPy | Process model development | Transfer function/state-space model estimation from data |

| Optimization Solvers | ACADOS [39], GRAMPC [39] | MPC optimization | Fast QP/nonlinear programming for real-time applications |

| Simulation Environments | MATLAB/Simulink, Python | Control algorithm testing | Virtual prototyping before hardware implementation |

| Communication Protocols | Modbus, Ethernet/IP, CAN | System integration | Industrial communication for sensor/actuator networks |

| 1,2,3-Tri-O-methyl-7,8-methyleneflavellagic acid | 1,2,3-Tri-O-methyl-7,8-methyleneflavellagic acid, CAS:69251-99-6, MF:C18H12O9, MW:372.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 21,23-Dihydro-23-hydroxy-21-oxozapoterin | 21,23-Dihydro-23-hydroxy-21-oxozapoterin | 21,23-Dihydro-23-hydroxy-21-oxozapoterin is a natural triterpenoid for research. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Relevance to Artificial Pancreas Systems

The comparative analysis of PID and MPC controllers provides valuable insights for artificial pancreas closed-loop control system design. Glucose regulation shares characteristics with many industrial processes: time delays (subcutaneous insulin absorption), measurable disturbances (meal announcements), changing dynamics (insulin sensitivity variations), and safety constraints (hypoglycemia avoidance).

MPC's predictive capabilities and explicit constraint handling make it particularly suitable for AP applications [42] [41]. The ability to incorporate meal announcements as feedforward disturbances and enforce safety constraints on predicted glucose values aligns well with clinical requirements. Recent research demonstrates that MPC can proactively mitigate postprandial hyperglycemia while preventing nocturnal hypoglycemia through optimization of future insulin delivery [42].

PID control offers advantages in implementation simplicity and computational efficiency, making it suitable for initial prototypes or embedded systems with limited processing capabilities [36]. Its clinical performance can be enhanced through gain scheduling to address circadian variations in insulin sensitivity [35].

Hybrid approaches, such as PID controllers with MPC-inspired constraint handling or cascade architectures, may leverage the strengths of both methodologies. The choice between control strategies should consider implementation complexity, computational requirements, and clinical performance specifications.

Diagram 2: Artificial pancreas control system structure

PID and MPC represent complementary approaches to feedback control with distinct advantages for different applications. PID control offers simplicity, reliability, and ease of implementation, while MPC provides sophisticated constraint handling and predictive capabilities. For artificial pancreas systems, both approaches offer viable pathways to automated glucose regulation, with selection dependent on performance requirements, implementation constraints, and clinical considerations.