Bridging the Loop: Overcoming Coordination Failures Between Glucose Sensing and Insulin Delivery in Diabetes Management

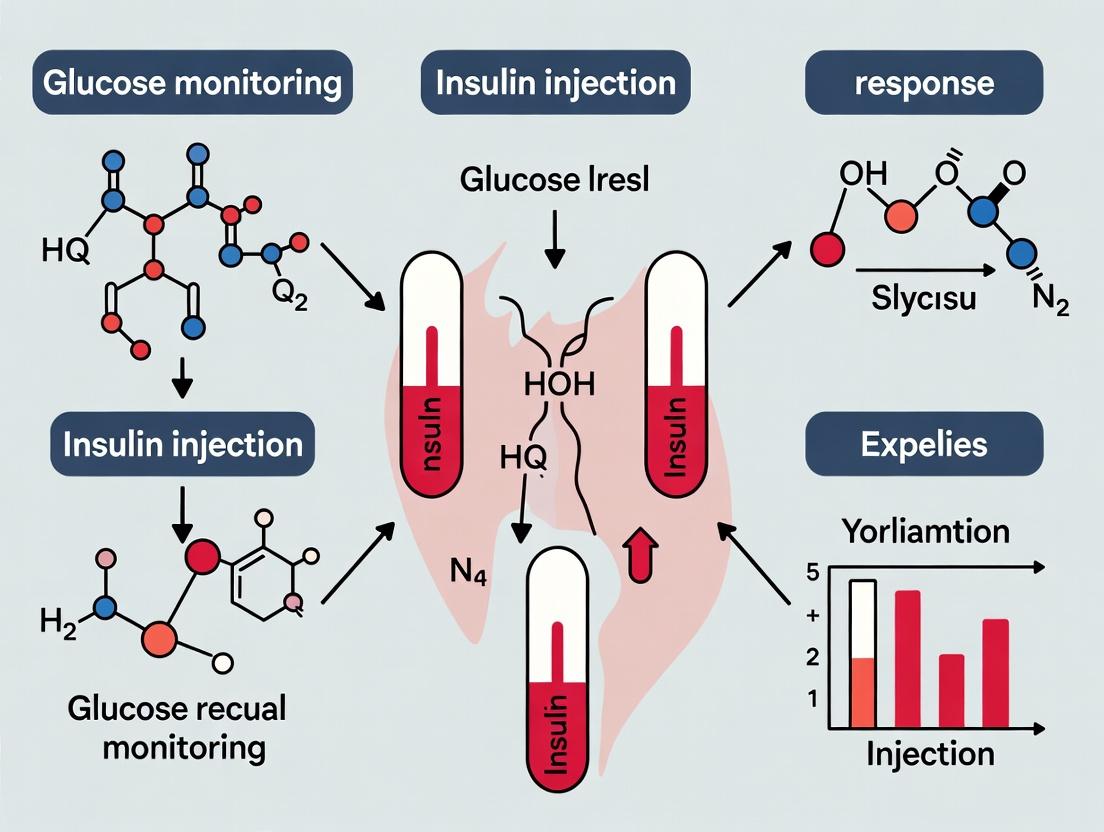

This article examines the critical challenge of poor coordination between glucose monitoring and insulin injection, a persistent barrier to optimal glycemic control.

Bridging the Loop: Overcoming Coordination Failures Between Glucose Sensing and Insulin Delivery in Diabetes Management

Abstract

This article examines the critical challenge of poor coordination between glucose monitoring and insulin injection, a persistent barrier to optimal glycemic control. We explore the foundational causes—including technological, physiological, and behavioral disconnects—and survey current methodologies from hybrid closed-loop systems to smart insulin pens and decision support algorithms. We provide a troubleshooting framework for common coordination failures and evaluate the comparative efficacy and validation standards of emerging integrated solutions. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current knowledge to guide the development of next-generation, truly synergistic diabetes management technologies.

Understanding the Disconnect: The Root Causes of Poor Coordination in Diabetes Management

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: In our in vitro closed-loop simulation, we observe significant overshoot in insulin response despite accurate glucose readings. What could be the cause? A: This is a classic manifestation of the physiological coordination gap. The issue likely stems from unaccounted-for sensor lag times combined with rapid-acting insulin pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics mismatches in your model.

- Troubleshooting Step 1: Verify and calibrate your glucose sensor delay parameters. The lag is not just technical but also physiological (interstitial fluid vs. plasma glucose).

- Step 2: Review your insulin action profile parameters (e.g., time-to-peak, duration). The table below summarizes key lag times to check in your simulation:

- Solution: Implement a predictive model (e.g., Kalman filter) to project glucose trends from incoming data, effectively "shifting" the signal forward to align with insulin action onset.

Quantitative Lag Time Data

| Lag Component | Typical Duration (Minutes) | Description & Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Sensor System Lag | 5-15 | Delay from blood glucose change to interstitial fluid reading and sensor processing. |

| Insulin Onset Lag | 10-20 | Time for subcutaneously injected insulin to begin appearing in the bloodstream. |

| Time-to-Peak Action | 60-120 | Duration to reach maximum glucose-lowering effect. Major source of mis-timing. |

| Manual Process Delay | 5-30+ | Human decision-making, preparation, and administration time in non-automated systems. |

Q2: Our manual cell culture experiment to correlate insulin receptor phosphorylation with glucose uptake yields high variability. How can we improve coordination? A: Variability often arises from manual timing misalignment between glucose stimulation and insulin injection steps. This manual process gap desynchronizes the signaling cascade.

- Troubleshooting: Audit your lab protocol. Are researchers consistently adhering to precise "time-zero" for both glucose and insulin additions across all trials?

- Solution: Implement the synchronized automated protocol below to eliminate human timing error.

Experimental Protocol: Synchronized Glucose-Insulin Stimulation for Cell Signaling Objective: To precisely coordinate glucose exposure and insulin stimulation for time-resolved analysis of downstream signaling (e.g., AKT phosphorylation). Key Reagents: See "Scientist's Toolkit" below. Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Seed and serum-starve HEK293 or adipocyte cells in 12-well plates for 16-24 hours.

- System Setup: Utilize a multi-channel pipette or, ideally, an automated liquid handler pre-loaded with reagents in temperature-controlled reservoirs.

- Synchronized Stimulation: a. For time-course experiments, initiate all wells simultaneously using an automated handler. b. Time Zero: Add pre-warmed high-glucose (25mM) medium to all wells. c. Precise Interval: At exactly t=2 minutes, add insulin (100 nM final concentration) to designated wells using a second automated channel. Control wells receive buffer.

- Termination: At defined timepoints (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30 min), rapidly aspirate medium and lyse cells directly in 1X Laemmli buffer to instantly halt signaling.

- Analysis: Proceed to Western Blotting for p-AKT (Ser473), total AKT, and other targets.

Q3: When analyzing data from continuous glucose monitors (CGM) and insulin pumps, how do we visually identify coordination gaps? A: Gaps are identified by plotting both data streams on a synchronized timeline and calculating the time differential between a glucose threshold event and the subsequent insulin dose.

Visualization: Identifying the Coordination Gap in Time-Series Data

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Coordination Research |

|---|---|

| Automated Liquid Handler | Eliminates manual timing errors in in vitro stimulation protocols; ensures precise, reproducible reagent addition. |

| Microfluidic Cell Culture Chips | Enables precise temporal control of glucose and insulin perfusion for studying real-time cellular responses. |

| Rapid-Acting Insulin Analogs (Lispro, Aspart) | Research-grade analogs with faster onset/offset used to minimize the inherent pharmacological lag time. |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies (p-AKT, p-IRS1) | Essential for measuring the timing and magnitude of early insulin signaling events post-stimulation. |

| Closed-Loop Simulation Software | Digital twin environment (e.g., UVa/Padova Simulator) to model and quantify the impact of various lag times in silico. |

| Time-Lapse Fluorescence Microscopy | For live-cell imaging of GLUT4 translocation, directly visualizing the endpoint of coordinated signaling. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Coordination in Glucose-Insulin Research

This support center provides guidance for common experimental challenges in research aimed at aligning glucose sensing with insulin action. The goal is to mitigate the risks of glycemic variability and hypoglycemia through improved mechanistic and therapeutic coordination.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: In our closed-loop system simulation, we observe persistent postprandial hyperglycemia followed by delayed hypoglycemia. What are the primary investigational paths?

- Answer: This pattern indicates a coordination failure, often between insulin pharmacodynamics (PD) and continuous glucose monitor (CGM) sensor lag. Investigate:

- Sensor Delay Characterization: Quantify the physiological and algorithmic latency of your CGM model. Compare interstitial vs. plasma glucose under dynamic conditions.

- Insulin Kinetics/PD Mismatch: Analyze if the insulin profile (e.g., rapid-acting analog) aligns with the meal absorption profile. A delayed peak action will exacerbate hyperglycemia, while a prolonged tail increases hypoglycemia risk, especially with delayed CGM feedback.

- Control Algorithm Aggressiveness: An overly aggressive controller will overcorrect for the hyperglycemic spike using data already delayed, leading to the subsequent low.

- Experimental Protocol: Quantifying System Latencies

- Objective: To measure the total lag between a glycemic stimulus and the insulin response command in a simulated closed-loop.

- Method:

- Use a glucose-insulin simulator (e.g., FDA-accepted UVA/Padova Simulator, Cambridge Simulator).

- Introduce a standardized meal challenge (e.g., 50g carbohydrates).

- Record timestamp of meal (T0), timestamp of CGM reading crossing threshold (T1), and timestamp of algorithm's insulin bolus command (T2).

- Sensor Lag = T1 - T0 (accounts for gastric emptying, absorption, sensor equilibration).

- Algorithmic/Response Lag = T2 - T1.

- Total System Lag = T2 - T0.

- Repeat with varying meal sizes, insulin types, and noise added to CGM signal.

FAQ 2: When evaluating a novel ultra-rapid insulin, how do we design an experiment to isolate its effect on reducing hypoglycemia risk from the effect of CGM accuracy?

- Answer: This requires a factorial study design that decouples the insulin variable from the monitoring variable.

- Experimental Protocol: Factorial Design for Component Isolation

- Design: 2x2 factorial: Insulin Type (Novel Ultra-Rapid vs. Standard Rapid) x Monitoring Input (Ideal Continuous Plasma Glucose vs. Real CGM with Noise).

- Method:

- Conduct in-silico trials using a cohort of virtual patients.

- Arm A: Ultra-Rapid Insulin + Ideal Glucose.

- Arm B: Ultra-Rapid Insulin + Real CGM.

- Arm C: Standard Rapid Insulin + Ideal Glucose.

- Arm D: Standard Rapid Insulin + Real CGM.

- Apply identical meal and exercise challenges.

- Primary Outcome: Time Below Range (<70 mg/dL).

- Analysis: Statistical interaction analysis will show if the benefit of ultra-rapid insulin is dependent on or independent of CGM quality.

FAQ 3: Our data shows high glycemic variability (GV) even with "good" Time in Range (TIR). What metrics should we prioritize to understand the coordination failure?

- Answer: TIR can mask frequent oscillations. Prioritize metrics that capture rate of change and asymmetry of excursions.

- Quantitative Data Summary: Key Glycemic Metrics

| Metric | Formula/Description | Target (General) | Indicates Coordination Failure When... |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time in Range (TIR) | % time 70-180 mg/dL | >70% | May be adequate, but insufficient alone. |

| Glycemic Variability (GV) | Coefficient of Variation (CV) | <36% | High CV (>36%) despite good TIR. |

| Low Blood Glucose Index (LBGI) | Risk index weighting hypoglycemic readings | Lower is better | Elevated, indicating frequent/profound lows. |

| High Blood Glucose Index (HBGI) | Risk index weighting hyperglycemic readings | Lower is better | Elevated, indicating frequent/profound highs. |

| Mean Amplitude of Glycemic Excursions (MAGE) | Average height of glucose swings exceeding 1 SD | <70 mg/dL | High value, showing large, un-damped oscillations. |

| Time to Peak (Postprandial) | Time from meal to peak glucose | Shorter is better | Prolonged, suggesting delayed insulin action. |

| Time to Nadir (Post-hypo treatment) | Time from hypoglycemia to recovery >70 mg/dL | Shorter is better | Prolonged, suggesting over-treatment or insulin stacking. |

Mandatory Visualizations

Diagram Title: Closed-Loop System Lag Contributors

Diagram Title: Mechanism Map: Coordination Failure to Clinical Risk

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Coordination Research |

|---|---|

| FDA-Accepted Glucose-Insulin Simulator (e.g., UVA/Padova) | Provides a virtual patient cohort for in-silico testing of algorithms, insulins, and sensors in a controlled, reproducible environment. Essential for factorial design studies. |

| Insulin Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) Models (e.g., Hovorka, Wilinska) | Mathematical descriptions of insulin absorption, distribution, and action. Used to simulate and compare novel insulin profiles against standard care. |

| CGM Error Models (e.g., AR(1) + White Noise) | Algorithms that add realistic sensor noise, bias, and lag to an ideal glucose signal. Critical for testing system robustness. |

| Standardized Meal & Exercise Protocols | Defined carbohydrate amounts and timings, and energy expenditure profiles. Enables consistent perturbation of the gluco-regulatory system for comparative studies. |

| Glycemic Variability Analysis Software (e.g., EasyGV, GlyCulator) | Calculates advanced metrics (MAGE, LBGI, HBGI, CONGA) from continuous glucose data to move beyond simple TIR analysis. |

| Control Algorithm Bench-Testing Platform | A software/hardware environment where a candidate control algorithm can be connected to a simulator or animal model in real-time, mimicking a closed-loop system. |

Welcome to the Technical Support Center. This resource is designed for researchers and drug development professionals working to overcome the interoperability challenges between glucose sensing and insulin delivery technologies. The following troubleshooting guides and experimental protocols are framed within the thesis of addressing the critical lack of coordination between these historically separate research domains.

Troubleshooting & FAQs

Q1: Our in-vitro closed-loop simulation is failing due to inconsistent data transmission latency between our custom continuous glucose monitor (CGM) sensor and the insulin pump driver. What are the primary points of failure to investigate?

A1: This is a classic interoperability issue stemming from siloed development. Investigate in this order:

- Protocol Handshake Failure: Verify the communication protocol (e.g., Bluetooth LE, custom RF) is identical on both sides. Use a protocol analyzer to check for repeated connection/disconnection events.

- Data Packet Corruption: Check the packet structure. A mismatch in endianness (byte order) between the CGM's microcontroller and the pump's receiver will corrupt data.

- Clock Synchronization Drift: The timestamp from the CGM and the pump's internal clock must be synchronized. Even a 100ms drift can destabilize a fast-acting insulin algorithm. Implement a Network Time Protocol (NTP) sync within your test rig.

- Electromagnetic Interference (EMI): The pump's motor driver can generate EMI that disrupts the CGM's analog front-end, especially in a benchtop setup. Increase physical separation and use shielded cabling.

Q2: When integrating a novel fluorescent glucose sensor with a microfluidic insulin delivery chip, we observe insulin denaturation at the interface. What is the likely cause and solution?

A2: The issue likely lies in the material biocompatibility and fluidic dynamics.

- Likely Cause: The sensor's flow cell may use an adhesive or polymer (e.g., PDMS) that is leaching uncrosslinked oligomers into the fluid path, or the interaction of the sensor's excitation wavelength is generating localized heat.

- Solution:

- Perform a cytotoxicity assay (ISO 10993-5) on the combined materials.

- Implement a passivation layer (e.g., PEG silane) on all wetted surfaces.

- Redesign the fluidic junction to minimize dead volume where fluid can stagnate and heat up. Use a stepped, coaxial interface instead of a simple T-junction.

Q3: Our algorithm for predicting hypoglycemic events performs well on CGM data alone but fails when insulin-on-board (IOB) data from the pump is introduced. How can we debug the algorithm's data fusion process?

A3: The failure indicates poor temporal alignment or incorrect weighting of the two data streams.

- Debugging Protocol:

- Temporal Alignment: Create a master clock for your experiment. Log all CGM readings (e.g., every 5 min) and pump insulin delivery events (every bolus/basal change) with nanosecond timestamps. Manually inspect for misalignment.

- Data Weighting Analysis: Run the algorithm with only CGM data (weight=1.0, IOB=0.0) and note performance. Gradually increase the IOB weight from 0.1 to 1.0 while monitoring the prediction error (see Table 1). The point where performance degrades indicates a flaw in how the IOB pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) model interacts with the CGM trend model.

Table 1: Algorithm Performance vs. IOB Data Weight

| IOB Data Weight | Prediction Sensitivity (%) | Prediction Specificity (%) | Mean Absolute Error (mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 (CGM only) | 88.5 | 92.1 | 14.2 |

| 0.2 | 87.9 | 93.0 | 13.8 |

| 0.5 | 82.1 | 90.5 | 18.7 |

| 0.8 | 75.4 | 85.2 | 24.3 |

| 1.0 | 70.1 | 80.9 | 29.5 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Cross-Technology Interference in a Benchtop Artificial Pancreas System

Objective: To quantify the electromagnetic and software interference between a commercial CGM transmitter and a research-grade insulin pump in a simulated wearable configuration.

Materials:

- Commercial CGM System (Transmitter & Receiver)

- Research Insulin Pump (with programmable driver)

- Saline solution (0.9% NaCl)

- Faraday cage or shielded enclosure

- Oscilloscope & Spectrum Analyzer

- Glucose clamp apparatus (for sensor stimulation)

- Data logging software (e.g., LabVIEW, custom Python)

Methodology:

- Place the CGM transmitter and insulin pump motor driver 5 cm apart (typical on-body distance) inside the Faraday cage.

- Initiate a stable basal insulin delivery profile (e.g., 0.05 U/hr).

- Simultaneously, use the glucose clamp to expose the CGM sensor to a stepped glucose concentration (80 → 180 → 80 mg/dL).

- Record the true CGM signal from its test points via the oscilloscope while simultaneously logging the transmitted data received by the CGM's official receiver.

- Introduce a large bolus command (1.0 U) to the pump. Capture the high-frequency EMI spectrum from the pump motor and the raw analog signal from the CGM sensor.

- Repeat at distances of 2 cm and 10 cm.

- Analysis: Correlate pump activation events with artifacts or dropouts in the CGM's raw signal. Calculate the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) degradation.

Protocol 2: Validating a Unified Communication Protocol for Research Devices

Objective: To implement and test a standardized data packet structure (based on IEEE 11073 PHD) for seamless data exchange between disparate research CGM and pump prototypes.

Materials:

- Two microcontroller units (MCUs) (e.g., ARM Cortex-M4).

- RF transceivers (e.g., 2.4 GHz).

- Glucose sensor simulator.

- Pump actuator simulator.

Methodology:

- Packet Design: Define a unified packet with fields: [Header][Timestamp][Device ID][Glucose Value/Insulin Command][CRC Checksum].

- Firmware Development: Program one MCU as the "CGM Simulator" to generate packets. Program the other as the "Pump Controller" to receive and parse them.

- Latency & Reliability Test: Transmit 10,000 packets at intervals from 100ms to 5 minutes. Log transmission and acknowledgement times.

- Error Injection Test: Deliberately corrupt packets (bit-flips) to test the CRC checking and re-transmission logic.

- Analysis: Calculate mean latency, packet loss rate, and system recovery time from errors (see Table 2).

Table 2: Unified Protocol Performance Metrics

| Metric | Target Performance | Observed Performance | Pass/Fail |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Transmission Latency | < 100 ms | 47 ms | Pass |

| Packet Loss Rate (10k packets) | < 0.1% | 0.05% | Pass |

| CRC Error Detection Rate | 100% | 100% | Pass |

| System Recovery after Error | < 1 sec | 0.8 sec | Pass |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Integration Research |

|---|---|

| PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane) | Used to create microfluidic channels for insulin delivery chips. Must be thoroughly cured and passivated to prevent analyte absorption. |

| PEG-Silane | A passivation reagent used to coat sensor and fluidic surfaces, creating a bio-inert, non-fouling layer to prevent protein (insulin) adhesion. |

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | The standard enzyme for electrochemical glucose sensing. Research focuses on stabilizing GOx in novel sensor membranes for longer life. |

| Fluorescent Glucose Analogs (e.g., 2-NBDG) | Used to validate and calibrate optical glucose sensors in cell-based or tissue-simulating environments. |

| Insulin Radiolabeling Kits (e.g., with I-125) | Allows for precise tracking of insulin adsorption to device materials and delivery kinetics in in-vitro setups. |

| Artificial Interstitial Fluid | A buffered solution mimicking the chemical composition of subcutaneous tissue, crucial for testing sensor performance and insulin stability in physiologically relevant conditions. |

System Integration & Signal Flow Diagram

Interoperability Failure Analysis Diagram

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

Q1: In our closed-loop insulin delivery in silico experiments, we observe persistent postprandial hyperglycemia despite accurate carbohydrate input. Which inherent physiological lag is most likely responsible, and how can we model it correctly?

A1: The most likely culprit is the delayed appearance of glucose in the bloodstream from the gut (glucose absorption lag), compounded by the delay in subcutaneous insulin reaching the systemic circulation (pharmacokinetic lag). The gut absorption lag can be 20-45 minutes, while the onset of action for subcutaneously injected rapid-acting insulin is still 15-30 minutes.

Troubleshooting Protocol: Implement a two-compartment absorption model for both glucose and insulin in your simulation.

- For Glucose: Use an oral glucose model with a gastric emptying compartment and an intestinal absorption compartment. Key parameter:

tau_g(time constant for gastric emptying). - For Insulin: Use a subcutaneous insulin model with two compartments (e.g., a depot compartment and plasma compartment). Key parameter:

tau_i(time constant for insulin absorption). - Validation Step: Compare your simulation's predicted plasma glucose curve against clinical data from mixed-meal tolerance tests. Mismatch in the first 60-90 minutes indicates inaccurate lag parameterization.

Q2: Our continuous glucose monitor (CGM) data consistently lags behind reference blood glucose measurements during rapid glucose changes, confounding our assessment of novel insulin analogs. What is the source and magnitude of this lag?

A2: The CGM lag is a combination of physiological and technical delays. The physiological lag (3-12 minutes) is due to the time for glucose to equilibrate from blood to interstitial fluid (ISF). The technical/algorithmic lag (5-15 minutes) is due to sensor response time and noise-filtering algorithms. The total lag can be 5-25 minutes.

Experimental Protocol to Quantify CGM Lag:

- Setup: Conduct a hyperglycemic clamp or intravenous glucose tolerance test in an animal or human study cohort.

- Measurement: Take frequent (every 5 min) reference venous or arterial blood samples for lab glucose analysis (YSI/Beckman analyzer).

- Data Synchronization: Precisely time-sync CGM and reference data streams.

- Analysis: Perform cross-correlation analysis or use a time-shift optimization method to find the time delay (

Δt) that maximizes the correlation between the two signals. Compute the mean absolute relative difference (MARD) atΔt.

Table 1: Quantitative Summary of Inherent Lag Times

| Lag Source | Typical Duration | Key Influencing Factors | Mitigation Strategies in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| CGM Physiological (Blood→ISF) | 3 - 12 min | Tissue perfusion, metabolism, sampling rate | Use vasodilators locally; validate with more frequent references. |

| CGM Technical/Algorithmic | 5 - 15 min | Sensor membrane, smoothing filters | Use raw sensor data streams; apply deconvolution algorithms. |

| SC Insulin Absorption (PK) | 45 - 120 min (to peak) | Injection site, local blood flow, formulation | Study intraperitoneal or intravenous delivery; use faster-acting analogs (e.g., Lyumjev). |

| Insulin PD Onset (Cell Signaling) | 15 - 30 min | Receptor binding, phosphorylation cascade | Investigate direct glucokinase activators or hepatic-focused pathways. |

| Gut Glucose Absorption | 20 - 45 min (to peak) | Meal composition, gastric emptying | Model with multi-compartment approaches; consider co-administration with pramlintide. |

Q3: When evaluating a novel insulin-receptor agonist in vitro, how do we design a protocol to isolate and measure the pharmacodynamic (PD) signaling lag, separate from pharmacokinetic (PK) absorption issues?

A3: To isolate PD lag, you must bypass the PK (absorption/distribution) phase by applying the compound directly to the target system.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Title: In Vitro Kinetics of Insulin Receptor Signaling Activation

- Cell Preparation: Use HEK-293 cells stably overexpressing the human insulin receptor (IR), or primary hepatocytes. Serum-starve for 6-8 hours.

- Rapid Agonist Application: Use a rapid perfusion system or fast pipetting to switch the medium to one containing a saturating dose (e.g., 100 nM) of the insulin analog/agonist. Record exact time of application as t=0.

- High-Frequency Sampling: At defined time points (e.g., 0, 30s, 1, 2, 5, 10, 15, 30, 60 min) post-application, rapidly lyse cells.

- Western Blot Analysis: Probe lysates for:

- Early Signal: Phospho-IR (Tyr1150/1151) and Phospho-IRS1.

- Intermediate Signal: Phospho-Akt (Ser473).

- Functional Output: Phospho-AS160 (for GLUT4 translocation studies in adipocytes).

- Data Analysis: Plot band intensity (normalized to total protein/loading control) vs. time. Define PD lag as the time from t=0 to a statistically significant increase in pIR. Define time-to-peak for each phosphorylation event.

Diagram Title: Isolating PD Signaling Lag from PK Absorption Lag

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Lag Research | Example/Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperinsulinemic-Euglycemic Clamp Platform | Gold-standard in vivo method to measure insulin action delay (peripheral & hepatic) by infusing insulin and glucose separately. | Human or large animal physiology lab; automated clamp systems. |

| Frequent Manual Sampling (Arterial/Venous Catheter) | Provides PK/PD reference data without device-related lags for calibrating CGM or validating insulin assays. | Bioanalytical method for insulin (ELISA/MSD) and glucose (YSI analyzer). |

| Rapid-Sampling In Vitro Perfusion System | Allows precise, sub-minute timing for adding/removing stimuli to measure early signaling kinetics. | Brand: BioLogic SFM-400; or custom-built laminar flow chambers. |

| Phospho-Specific Antibody Panels | Critical for mapping the time-course of insulin signaling cascade activation (pIR, pIRS, pAkt, pAS160). | Cell Signaling Technology, PhosphoSolutions. |

| Tracer Compounds (Stable Isotope Glucose) | Allows modeling of endogenous glucose production and glucose disposal rates independently during dynamic tests. | [6,6-²H₂]-glucose; infusion pumps for primed-constant infusion. |

| UV-Crosslinkable Insulin Analogs | Used to "freeze" the momentary in vivo state of insulin-receptor binding and internalization for spatial/temporal analysis. | Photoactive insulin derivatives (e.g., Bpa⁵¹⁶-insulin). |

| Mathematical Modeling Software | For fitting PK/PD models (MinMod, SAAM II) and simulating closed-loop control with incorporated lags. | MATLAB/Simulink, R, Python (with SciPy, PySB). |

Q4: How do we mathematically model the combined effect of multiple sequential lags (CGM + Insulin PK) for designing a predictive hypoglycemia alarm?

A4: The cascaded lags are best modeled as a series of time-delay differential equations (DDEs) or using a chain of Laplace transforms with transport delays.

Protocol for Building a Composite Lag Model:

- Define Individual Transfer Functions:

- CGM Lag:

G_cgm(s) = e^(-s*τ_cgm) / (α*s + 1)whereτ_cgmis the pure delay andαis the sensor time constant. - Insulin PK Lag: A two-compartment model:

I_plasma(s) / I_sc(s) = (1/(V1*s)) * (k1/(s+k2)) * e^(-s*τ_sc).

- CGM Lag:

- Cascade the Models: The perceived glucose error signal (

e(t)) for a controller becomes:e(t) = y_cgm(t) - target, wherey_cgm(t)is the delayed and filtered version of true blood glucose. - Implement in Simulation:

- Validation: Tune the lag parameters (

τ_cgm, τ_sc, etc.) by minimizing the error between your model's prediction and clinical dataset outcomes (e.g., from the OhioT1DM dataset).

Diagram Title: Cascaded Lag Model for Closed-Loop Insulin Delivery

This technical support center provides guidance for researchers and drug development professionals addressing coordination challenges between glucose monitoring and insulin injection research. The following troubleshooting guides and FAQs are framed within the broader thesis of improving this critical coordination.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

Q1: Our clinical trial data shows inconsistent correlation between continuous glucose monitor (CGM) readings and subsequent insulin dosing adherence. What are the primary human factor variables we should isolate?

A1: Inconsistent correlations often stem from unaccounted cognitive load variables. You must isolate and measure:

- Decision Fatigue: Track the time of day of dosing decisions against deviation from protocol.

- Alert Burden: Quantify the number of CGM alerts/notifications preceding a dose. High alert volumes precede user "alert fatigue" and ignored readings.

- Context Switching Cost: Measure if dosing occurs during a separate task (e.g., work meeting, driving) vs. a dedicated health management period.

Experimental Protocol for Isolation:

- Design: A 7-day observational study with type 1 diabetes participants using a CGM and smart insulin pen.

- Data Streams: Synchronize timestamped data for: CGM readings, all device alerts, insulin doses (time and amount), participant-reported activity via a simplified ecological momentary assessment (EMA) app.

- Analysis: Perform a multivariable regression where the dependent variable is the absolute difference between actual insulin dose and algorithm-suggested dose. Independent variables should include: number of CGM alerts in past 60 minutes, time of day, reported concurrent activity type.

Q2: How can we experimentally quantify the "burden" of a hybrid closed-loop system setup for an elderly participant in a study?

A2: Burden is a composite metric. Use the following validated tools and objective measures:

| Metric Category | Specific Measurement Tool | Quantitative Output / Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Subjective Burden | Diabetes Technology Burden Questionnaire (DTBQ) | 33-item scale; higher score indicates greater burden. |

| Cognitive Load | NASA-Task Load Index (NASA-TLX) | 6-subscale score (Mental, Physical, Temporal Demand, Performance, Effort, Frustration). |

| Usability | System Usability Scale (SUS) | Score from 0-100. |

| Objective Time Burden | Direct Observation & Timing | Mean time (minutes) to initialize system, respond to alerts, and perform daily maintenance. |

Experimental Protocol for Quantification:

- Recruitment: Enroll participants aged 65+ with type 2 diabetes, naive to hybrid closed-loop systems.

- Training: Provide standardized training on the specific system.

- First-Use Session: Videotape the participant's first independent setup and calibration. Record time-to-completion and number of errors (requiring intervention).

- Post-Session Metrics: Immediately administer NASA-TLX and relevant SUS items.

- Post-Study Metric: After 14 days, administer the full DTBQ and SUS.

Q3: We suspect "calculation aversion" is causing poor adherence to titration protocols in our insulin study. How can we redesign the protocol to mitigate this?

A3: "Calculation aversion" is a key human factor. Redesign your protocol to eliminate manual arithmetic.

Original Protocol Burden: "Check fasting glucose daily. If average over past 3 days is above target, increase nightly basal insulin by 2 units. If below target, decrease by 1 unit."

Redesigned Protocol (Reduced Burden): "Use the provided study app. It will:

- Automatically read your fasting glucose from your connected meter/CGM.

- Calculate the 3-day average.

- Display a clear message: 'This week's dose: units. Last week's dose: [Y] units.'" The calculation is removed from the user's mental workload and performed reliably by the system.

Q4: What are common data synchronization failures between glucose and insulin data streams, and how can we resolve them?

A4: Failures primarily occur at the device, software, or human action layer.

| Failure Point | Symptom | Troubleshooting Guide |

|---|---|---|

| Time Synchronization | Insulin dose timestamps are hours off from CGM event logs. | Solution: Mandate automatic network time (NTP) sync for all apps/ devices. Include a time-discrepancy check in data QA scripts. |

| Manual Logging Delay | Manually logged meals or doses show "clustering" at convenient times (e.g., end of day). | Solution: Use Bluetooth-connected devices (pens, meters) that timestamp events automatically. Supplement with prompted EMA entries. |

| Device Pairing Loss | CGM data is present but corresponding insulin data from a "smart" pen is missing for a period. | Solution: Implement a daily device connectivity check within the study app. Provide clear visual feedback (e.g., "Pen Connected" icon). |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Human Factors Research |

|---|---|

| Bluetooth-Enabled Smart Insulin Pen | Captures objective, timestamped dosing data (dose amount, time) without relying on user recall or manual entry. |

| Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) API Access | Allows researchers to pull raw, timestamped glucose and alert data directly from the manufacturer's cloud for precise synchronization. |

| Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) Platform | Enables real-time, in-context subjective data collection (e.g., burden, cognitive load, situational context) via a participant's smartphone. |

| Data Synchronization Hub Platform | A secure middleware (e.g., Glooko, Tidepool) or custom-built platform that ingests and time-aligns disparate data streams (CGM, insulin, activity) for unified analysis. |

| Usability Testing Software | Tools like UserTesting.com or Morae for recording and analyzing participant interactions with study devices and apps, identifying points of confusion. |

Experimental Workflow & Pathway Diagrams

Diagram Title: Data Integration Workflow for Human Factors Research

Diagram Title: Cognitive Load Pathway to Dosing Error

Engineering Synergy: Current and Emerging Methodologies for Integrated Control

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

FAQ: Algorithm & Sensor Integration Q1: Our in-silico model shows the control algorithm persistently over-corrects for postprandial glucose spikes, leading to late-onset hypoglycemia. What are the primary tuning parameters to investigate? A1: Focus on the postprandial insulin feedback gain and the insulin-on-board (IOB) constraints. Excessive postprandial gain or an overestimated IOB half-life can cause this. Adjust the IOB decay model and implement stricter IOB limits during predicted high-glycemic-index meals. Refer to Table 1 for key parameter targets.

Q2: During animal trials, we observe a systemic inflammatory response causing sustained sensor sensitivity drift. How can we decouple inflammation from true hypoglycemia in the algorithm's diagnostic module? A2: Implement a multi-signal diagnostic layer. Algorithmic intelligence must integrate:

- C-Reactive Protein (CRP) trend data from a secondary assay.

- Interstitial Fluid (ISF) kinetics model to identify abnormal lag times.

- Heart rate variability (HRV) data from a bio-telemetry implant. A decision tree logic (see Diagram 1) should weight these inputs to flag "Low Confidence" sensor data, triggering a fallback to conservative basal rates.

Q3: The hybrid closed-loop (HCL) system fails to initiate auto-correction boluses for rising glucose trends in our primate model, despite manual bolus working. What is the likely root cause? A3: This typically indicates a fault in the "Meal Detection" or "Rise Detection" module, not the correction algorithm itself. Verify:

- Sensor noise filtering thresholds are not set too high, obscuring a true rise.

- The rate-of-change (ROC) trigger is calibrated for the model's physiology (primate ROC may differ from human proxies).

- Auto-mode is actually active; confirm the system isn't stuck in a "basal-only" safety state due to a missed calibration.

Experimental Protocol: In-Vivo Validation of Algorithm Adaptation Title: Protocol for Validating Adaptive Insulin Feedback Parameters in a Minipig HCL Model. Objective: To test an algorithm's ability to self-adjust insulin sensitivity factor (ISF) based on circadian patterns.

- Implant: Continuous glucose monitor (CGM) and insulin pump.

- Baseline Period (72 hrs): Run standard HCL algorithm. Collect glucose time-in-range (TIR) and insulin delivery data.

- Algorithm Adaptation Phase: Enable the adaptive ISF module. The algorithm analyzes nocturnal vs. diurnal insulin requirement patterns.

- Challenge Phase: Introduce standardized mixed-meal tests at both day (active) and night (rest) phases.

- Metrics: Compare glucose RMSE, TIR (70-180 mg/dL), and hypoglycemic events between Baseline and Adapted phases for night vs. day.

- Endpoint Analysis: Use paired t-test on RMSE data (see Table 2).

Key Data Tables

Table 1: Core Algorithm Parameters for Tuning Postprandial Response

| Parameter | Typical Range | Effect of Increasing Value | Primary Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Postprandial Gain | 1.0 - 3.0 | More aggressive correction of high glucose | Late-phase hypoglycemia |

| IOB Half-Life | 60 - 120 min | Longer assumed insulin action | Insulin stacking, hypoglycemia |

| ROC Trigger (mg/dL/min) | 1.5 - 3.0 | Earlier meal detection | False positives, over-delivery |

| Target Glucose (mg/dL) | 110 - 140 | Tighter control | Increased hypoglycemia risk |

Table 2: Sample Experimental Results - Adaptive ISF Protocol (n=6 minipigs)

| Phase | Avg. Glucose (mg/dL) | TIR (%) | Nocturnal Hypo Events (<70 mg/dL) | Glucose RMSE (vs. Target) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (Static ISF) | 145 ± 18 | 68.2% | 4 | 24.5 |

| Adaptive ISF Active | 132 ± 12 | 82.7% | 1 | 16.1 |

| p-value | <0.05 | <0.01 | 0.08 | <0.01 |

Signaling & Diagnostic Pathway Visualizations

Diagram 1: Multi-Signal Diagnostic for Sensor Anomaly

Diagram 2: AHCL Algorithm Core Feedback Loop

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in HCL/AHCL Research |

|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Glucose Tracers | Allows precise kinetic modeling of glucose appearance/disappearance, critical for validating algorithm state estimates. |

| High-Fidelity CGM Sensor Arrays | Research-grade sensors with raw data output for developing and testing noise filtration and lag-compensation algorithms. |

| Programmable Insulin Analog Infusates | Enables testing of novel ultra-rapid or hepatic-preferential insulins within the closed-loop context. |

| Multiplex Cytokine Assay Panels | Quantifies inflammatory markers to correlate with sensor performance degradation and refine diagnostic modules. |

| Telemetric Physiologic Monitors (ECG/Temp/Activity) | Provides covariate data (HR, HRV, activity) for context-aware algorithmic adjustments and safety interlocks. |

| In-Silico Simulation Platform (e.g., UVA/Padova Simulator) | Provides a safe, initial testbed for algorithm changes using accepted metabolic models before animal studies. |

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Center

This resource addresses common technical and experimental challenges when implementing device interoperability protocols in a research setting focused on coordinating glucose monitoring and insulin delivery.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our in-house simulator cannot decode data packets from a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) using the DIDI protocol. What are the first steps?

- A: First, verify the conformance statement provided by the CGM manufacturer. Ensure your simulator is using the correct version of the IEEE 11073-10425 standard (the core of DIDI). Check the

MDS(Medical Device System) object attributes for errors. Commonly, the mismatch is in theSystem-ModelorSystem-IDfields. Use a packet analyzer (e.g., Wireshark) to capture raw data and compare it against the standard's ASN.1 schema.

- A: First, verify the conformance statement provided by the CGM manufacturer. Ensure your simulator is using the correct version of the IEEE 11073-10425 standard (the core of DIDI). Check the

Q2: When integrating an automated insulin delivery (AID) research system, we encounter significant latency (>5 minutes) between glucose data receipt and pump command. How can we isolate the cause?

- A: This requires systematic isolation. Follow this workflow: 1) Bypass the interoperability layer and inject simulated glucose data directly into your control algorithm to test its inherent latency. 2) Re-introduce the DIDI data translation layer alone with simulated data. 3) Finally, test with the physical CGM and DIDI translator. The issue is often in the middleware's event-handling loop or in network configuration (e.g., excessive polling intervals instead of unsolicited reports). See Table 1 for benchmark metrics.

Q3: We are planning a preclinical study comparing two insulin pump APIs. What are the key interoperability parameters to measure?

- A: You must establish a standardized test bench. Key quantitative parameters to measure and compare are listed in Table 2. Essential qualitative factors include the clarity of the API's error codes and the robustness of its safety-critical command set (e.g., hard-stop bolus, suspend).

Q4: How do we ensure our research using the Tidepool Platform or OpenAPS protocols is reproducible?

- A: Document the exact version of the open-source protocol specification and any vendor extensions used. For Tidepool, specify the

tide-mobile-clientanduploaderversions. For OpenAPS, document theoref0commit hash. All data transformations (e.g., smoothing of CGM data) must be described and their code archived. Use the provided "Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking Data Flow Latency" as a template for methodology detail.

- A: Document the exact version of the open-source protocol specification and any vendor extensions used. For Tidepool, specify the

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Erratic or Missing Data in a Multi-Vendor Research Stack

- Symptoms: Gaps in timestamped glucose records, insulin dose logs that fail to appear in the data aggregator.

- Diagnostic Steps:

- Validate Individual Streams: Confirm each device (CGM, pump) logs data correctly to its native proprietary application.

- Check Translator Integrity: Verify the middleware device or software (e.g., insulin pump communication driver, Bluetooth-to-IP bridge) is powered and has a stable connection. Restart it.

- Review Log Files: Examine the application log files of your research data aggregator (e.g., your custom Python service, Nightscout instance) for errors. Common errors are

"CRC_FAIL","TIMEOUT", or"UNSUPPORTED_ATTRIBUTE". - Protocol Sniffing: Use a dedicated protocol analyzer (e.g., for Bluetooth Low Energy) to confirm the physical layer communication is intact.

- Solution: 90% of issues are resolved at Step 3. Update or re-configure the translator software based on the specific error. Ensure no other research software is concurrently trying to access the same device, causing a resource lock.

Issue: Inconsistent Results When Replaying Archived Data

- Symptoms: An algorithm behaves differently when processing live data from an interoperable system versus its validated performance on a static, archived dataset.

- Diagnostic Steps:

- Metadata Audit: Archived research datasets often strip or anonymize crucial metadata. Check for the presence of

device_sn,system_id,timezone_offset, andclock_driftfields. - Timestamp Alignment: Live data may have millisecond-level jitter. Apply the same smoothing or binning function you used in your original analysis to the live stream.

- State Persistence: Verify that your algorithm's state variables (e.g., insulin-on-board, rate-of-change trend) are being initialized correctly upon system start in the live test, matching the archived run's starting state.

- Metadata Audit: Archived research datasets often strip or anonymize crucial metadata. Check for the presence of

- Solution: Create a "replay harness" that ingests the archived data but uses the exact same data ingestion and preprocessing module as your live interoperability setup. This isolates the difference to the data input pipeline.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Benchmark Latency Metrics for Key Interoperability Components (Ideal Research Environment)

| Component | Protocol | Measured Latency (Mean ± SD) | Acceptable Threshold for AID Research | Primary Influence Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGM to Smartphone | Bluetooth LE (Manufacturer Specific) | 12 ± 5 s | < 60 s | Device bonding & polling rate |

| Data Translation (DIDI Layer) | IEEE 11073-10425 | 180 ± 50 ms | < 500 ms | Middleware processor speed |

| Cloud Upload/Download | HTTPS/REST API | 2.5 ± 1.5 s | < 10 s | Network bandwidth & SSL handshake |

| Control Algorithm Cycle | N/A | 50 ± 20 ms | < 200 ms | Code optimization & hardware |

| Pump Command Delivery | ISO/IEEE 11073-10419 (DIDI Pump) | 800 ± 200 ms | < 2 s | Radio frequency interference |

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Insulin Pump API Suites for Research

| Parameter | Pump API A (Commercial) | Pump API B (Open Research) | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Command Latency | 1200 ms | 850 ms | Time from send() to delivery confirmation |

| Data Granularity | 5-min basal logs, per-bolus | 1-min basal logs, per-pulse | Log audit via vendor tool vs. open log |

| Error Code Detail | 15 generic codes | 48 specific codes | Analysis of API documentation |

| Safety Lockouts | Mandatory 2-min suspend | Configurable 0-30 min | Experimental testing with override |

| Real-time Status | Battery, Reservoir | + Occlusion, Self-test status | Polling frequency capability |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Benchmarking End-to-End Data Flow Latency in an Interoperable Research System

Objective: To quantitatively measure the total latency from glucose sensing to actionable insulin delivery command in a multi-device, protocol-driven research setup.

Methodology:

- Synchronization: All system components (CGM simulator, interoperability middleware, research laptop, insulin pump simulator) are time-synchronized using Network Time Protocol (NTP) to a master clock with millisecond precision.

- Timestamp Injection: A glucose simulator generates a precise glucose value

G_tat timeT0. This value is packetized withT0embedded in the payload. - Pathway Instrumentation: Each system component is instrumented to log the arrival time (

T_arr) and departure time (T_dep) of the data packet containingG_t.- Key nodes: CGM Emulator output, DIDI Translator input/output, Control Algorithm input/output, Pump API gateway.

- Data Collection: The experiment is repeated

n=500times over a 72-hour period, simulating various system loads. - Calculation: Latency at each node

L_node = T_dep - T_arr. Total latencyL_total = T_pump_cmd_received - T0. - Analysis: Statistical analysis (mean, standard deviation, 95th percentile) is performed on

L_totaland per-node latencies to identify bottlenecks.

Protocol: Evaluating Protocol Fidelity Using Signal Replay

Objective: To assess the data integrity and fidelity of an open interoperability protocol (e.g., Tidepool's tide-whisperer) versus a manufacturer's proprietary protocol.

Methodology:

- Capture: Use a Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) hardware tool (with ethical/legal approvals) to simultaneously capture raw data packets from a device using both the proprietary RF protocol (Signal A) and the open protocol translation (Signal B).

- Stimulus Generation: A scripted series of physiological events (rapid glucose rise, plateau, fall) and device events (calibration, suspend, resume) is enacted on the device.

- Data Alignment: The two time-series data streams are aligned using a shared, injected event marker (e.g., a unique 10-digit timestamp).

- Comparison: For each recorded parameter (glucose value, insulin dose, device alert), calculate the discrepancy

Δ = Value_A - Value_Band the time skewΔt = Timestamp_A - Timestamp_B. - Validation: Establish a fidelity threshold (e.g.,

Δ_glucose < 0.1 mmol/L,Δt < 5 s). The percentage of data points meeting these thresholds defines the protocol fidelity score.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Interoperability Research |

|---|---|

| Protocol Analyzer (e.g., Ellisys BLE) | Captures and decodes raw Bluetooth Low Energy packets to debug physical/link layer communication between devices and translators. |

| Medical Device Simulators | Software/hardware that emulates CGMs and pumps, generating predictable, repeatable data streams for controlled experiments. |

| Reference Glucose Analyzer | Laboratory instrument (e.g., YSI Stat) provides ground-truth glucose values to calibrate and validate the accuracy of data streams from interoperable CGMs. |

| Precision Time Protocol (PTP) Grandmaster Clock | Enables microsecond-level synchronization across all research hardware, essential for precise latency measurement. |

| Data Anonymization Suite | Software that scrubs Protected Health Information (PHI) from real-world data logs while preserving crucial temporal and device metadata for research. |

| Middleware Development Kit (e.g., from Continua) | Provides reference code and tools to implement IEEE 11073 (DIDI) standards, accelerating custom translator development. |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: DIDI Data Flow in AID Research

Diagram 2: Protocol Stack for Device Integration

Diagram 3: Troubleshooting Logic for Data Gaps

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs for Research Setups

This technical support center is designed for researchers conducting experiments to address coordination failures between glucose monitoring and insulin injection. The guides below focus on common issues when integrating smart insulin pens and connected caps with experimental monitoring systems.

FAQs & Troubleshooting

Q1: In our closed-loop simulation, the timestamp data from the connected cap (e.g., Timesulin, Gocap) is not synchronizing with our continuous glucose monitor (CGM) data stream. How do we resolve this temporal misalignment?

A: This is a common data fusion issue. Follow this protocol:

- Protocol for Temporal Synchronization:

- Equipment: Smart Pen/Cap, Reference NTP server, Data logging server.

- Method: Before initiating the experiment, implement a unified Network Time Protocol (NTP) client on all data-logging devices (CGM receiver, smartphone receiving cap data, experimental control PC). Use a local NTP server for minimal latency.

- Validation: Perform a "sync pulse" at the start and end of each experimental session: manually trigger a simultaneous, unique marker (e.g., a specific small insulin dose, a button press) recorded by all systems. Use these markers to correct for any residual constant offset in post-processing.

Q2: The Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) signal from our research-grade connected cap is frequently dropping during in-vivo animal studies, corrupting dose-logging data. What are the mitigation strategies?

A: Signal loss is often due to physical obstruction or interference.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Reproducible Placement: Standardize the position and orientation of the relay device (smartphone/BLE hub) relative to the animal enclosure.

- Interference Check: Identify and power down potential sources of 2.4 GHz interference (Wi-Fi routers, other lab equipment).

- Data Integrity Protocol: Implement application-layer data redundancy. Program the cap's firmware (if accessible) or the receiving app to send each dose log packet three times with a 100ms delay. On the receiver, use a "majority vote" system to confirm the correct data packet.

Q3: When validating insulin dose accuracy for a new pen prototype, our gravimetric analysis shows a high coefficient of variation (>5%). How should we isolate the error source?

A: Follow a systematic error isolation workflow.

- Experimental Protocol for Error Source Identification:

- Step 1 - Pen Mechanism Test: Disconnect the cap. Use a high-precision microbalance (0.1 mg resolution) to weigh the pen before and after a series of fixed-dose injections into air. Calculate actual delivered dose (1 unit ≈ 10 µL ≈ 10.096 mg for Humalog). This isolates mechanical pen error.

- Step 2 - Cap Sensor Calibration: Re-attach the cap. Perform injections without the cap's logging function active. Manually record the cap's displayed dose estimate versus the gravimetric ground truth to generate a calibration curve.

- Step 3 - Integrated System Test: Repeat with the cap's automatic logging enabled to validate the full system's data accuracy.

Q4: Our data pipeline from multiple smart pen brands (NovoPen 6, InPen, companion caps) produces heterogeneous data formats. What is the recommended method for creating a unified dataset for analysis?

A: Implement an Extract, Transform, Load (ETL) framework.

- Methodology:

- Extract: Use official SDKs/APIs where available (e.g., Novo Nordisk's

ConnectAPI, Medtronic'sCareLink). For reverse-engineered protocols, maintain a separate, version-controlled code library. - Transform: Create a common data schema. Map all vendor-specific fields to this schema. Key mandatory fields should include:

Device_ID,Timestamp_UTC,Insulin_Dose_IU,Injection_Flag (Bolus/Basal),Data_Quality_Score. - Load: Ingest the transformed data into a structured database (e.g., SQLite for small studies, PostgreSQL for larger cohorts) with strict data type validation.

- Extract: Use official SDKs/APIs where available (e.g., Novo Nordisk's

Table 1: Comparative Technical Specifications of Representative Devices in Research

| Device/Add-on | Communication | Dose Detection Method | Dose Logging Accuracy (as reported) | API/SDK for Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medtronic InPen | Bluetooth to App | Integrated | >99% | Yes (Limited) |

| NovoPen 6 & 7 | Bluetooth to App | Integrated | >99% | Yes (Novo Nordisk Connect) |

| Gocap | Bluetooth to App | Rotary Motion Sensor | ~97-99% | No (Data export via app) |

| Timesulin/Capen | Bluetooth to App | Timer-based (Dose inferred) | N/A (Timing only) | No |

Table 2: Common Data Artifacts and Correction Factors in Clinical Studies

| Artifact Type | Typical Frequency | Recommended Correction/Filtering Method |

|---|---|---|

| BLE Packet Loss | 2-5% in uncontrolled env. | Use forward error correction; interpolate from timestamp patterns. |

| Incorrect Time Zone Setting | ~10% of user-initiated data | Validate against CGM epoch time; apply offset. |

| "Ghost" Doses (Sensor False Positive) | <1% | Apply threshold filter (e.g., discard logged doses < 0.5 IU). |

| Missed Doses (User forgets cap) | 15-25% in real-world use | Flag sessions with >24h cap inactivity; statistical imputation may be required. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating Injection-to-Monitor Coordination Delay

Objective: Quantify the systemic delay between insulin injection (logged by smart cap) and the onset of detectable glucose change (via CGM) in a controlled setting.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- Subject Cohort: Porcine model (n=6), fasted.

- Insulin: Rapid-acting analog (Lispro/Aspart), 0.15 U/kg dose.

- Smart Insulin Pen & Cap: e.g., NovoPen 6 with integrated logging.

- CGM: Research-use CGM (e.g., Dexcom G7 with remote API).

- Reference Analyzer: YSI 2900 STAT Plus for venous blood glucose.

- Data Hub: Raspberry Pi 4 running custom Python script to time-sync pen data and CGM stream via NTP.

- Clamp Setup: (Optional) Euglycemic clamp apparatus to measure insulin pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics.

Procedure:

- Baseline Period (-30 to 0 min): Insert CGM. Stabilize subject. Confirm euglycemia (5.6-7.0 mmol/L).

- Synchronization Pulse (t=0 min): Using NTP-synchronized clocks, record a manual sync marker on all data streams.

- Injection & Logging (t=1 min): Administer the standardized bolus using the smart pen. The connected device automatically logs the exact timestamp and dose.

- High-Frequency Sampling (t=1 to 180 min): Collect CGM data at 1-min intervals via API. Draw venous samples for YSI analysis at t= -5, 0, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, 150, 180 min.

- Data Analysis: Align datasets using the sync pulse. Calculate the delay (

t_CGM_onset - t_injection_log) whereCGM_onsetis defined as the first timepoint where the CGM trend shows a consistent negative slope exceeding 0.1 mmol/L/min.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Smart Pen Coordination Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| NTP Server Hardware | Precise time synchronization across all data-logging devices. | Microchip GPS NTP Server; local Raspberry Pi NTP server. |

| Research CGM with API | Enables high-frequency, programmable data extraction for correlation with injection events. | Dexcom G6/G7 (Research API), Abbott Libre Pro H. |

| Data Fusion Platform | A software environment to ingest, align, and analyze heterogeneous time-series data. | Custom Python (Pandas, NumPy), LabKey Server, REDCap. |

| Gravimetric Validation Kit | Gold-standard for verifying injected insulin dose accuracy of pen-cap systems. | High-precision microbalance (0.1mg), controlled environment chamber. |

| BLE Protocol Analyzer | For debugging connectivity issues and reverse-engineering data streams from non-open devices. | Nordic Semiconductor nRF Sniffer, Frontline BLE Protocol Analyzer. |

| Glucose Clamp System | The reference method for quantifying the pharmacodynamic response to a logged insulin dose. | Biostator or custom clamp system using variable glucose/insulin infusion. |

Visualization: Research Workflows and Data Relationships

Data Flow in Smart Pen & CGM Coordination Research

Troubleshooting Logic for Dose Inaccuracy

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

FAQ 1: During in vivo dual-hormone (Insulin & Glucagon) infusion studies, we observe exaggerated counter-regulatory responses. What could be causing this?

- Answer: This is often due to suboptimal hormone dosing ratios or timing. Glucagon's hyperglycemic effect is potent but transient. An excessive or mistimed glucagon bolus can overcorrect hypoglycemia, triggering a subsequent excessive insulin release. Consult Table 1 for refined dosing parameters. Ensure your algorithm's hypoglycemia prediction horizon is calibrated to your model's metabolic rate. Use the "Dual-Hormone Algorithm Tuning Protocol" below.

FAQ 2: In our pramlintide co-infusion experiments, we see unacceptable variability in postprandial glucose suppression. How can we improve consistency?

- Answer: Variability frequently stems from pramlintide's pharmacokinetic profile delaying gastric emptying. Inconsistent meal timing relative to infusion start is a common culprit. Standardize the pre-meal lead time (typically 30-60 minutes). Also, check the stability of your pramlintide solution; it can adhere to tubing. Use the "Pramlintide-Adjunctive Therapy Workflow" and ensure you are using a non-adsorptive infusion line. See "Research Reagent Solutions" for recommended materials.

FAQ 3: Our artificial pancreas (AP) algorithm fails to stabilize glucose in the presence of stress hormones (e.g., in a surgical model). How can we make the system more robust?

- Answer: Single-hormone (insulin-only) AP systems are inherently vulnerable to hyperglycemic stressors. This highlights the thesis context of poor coordination. Implementing a glucagon safety module that uses a separate, stricter glucose threshold during predefined "stress periods" can improve coordination. Integrate a secondary, model-predictive controller for glucagon that activates only when stress biomarkers (e.g., catecholamines) are elevated. See the "Stress-Response Signaling Pathway" diagram.

FAQ 4: We are getting inconsistent results when testing insulin-pramlintide combinations in isolated islet perfusion assays. What are the critical parameters to control?

- Answer: Focus on perfusion buffer composition and hormone sequencing. Pramlintide's primary effect is to suppress glucagon secretion; this is glucose-dependent. Ensure your perfusion switches from a low-glucose (e.g., 3mM) to high-glucose (e.g., 11mM) buffer at a precise time after pramlintide pre-perfusion. Maintain a physiological Ca²⁺ concentration (1.2-1.3mM). Follow the "Islet Perfusion Sequential Protocol" below.

Table 1: Comparative Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Parameters for Adjunctive Therapies

| Parameter | Rapid-Acting Insulin (Aspart) | Glucagon (rDNA) | Pramlintide (Analogue) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset of Action | 10-20 min | ~8-10 min | ~30 min (for gastr. empty.) |

| Time to Peak | 60-90 min | ~30-40 min | ~2 hours |

| Half-life (t½) | 60-90 min | ~8-18 min | ~50 min |

| Key Mechanism | Promotes glucose uptake | Hepatic glycogenolysis & gluconeogenesis | Slows gastric emptying, suppresses glucagon |

| Typical Adj. Dose Ratio | 1.0 (Baseline) | 1:10 to 1:20 (Ins:Gluc, mcg) | 1:30 to 1:60 (Ins:Pram, mcg) |

Table 2: Algorithm Performance Metrics in Silico (UVa/Padova Simulator)

| Algorithm Type | Time in Range (70-180 mg/dL) | Hypoglycemia Events (<54 mg/dL) | Hyperglycemia Events (>250 mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin-Only AP | 78.2% ± 5.1% | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± 1.2 |

| Insulin+Glucagon AP | 85.7% ± 3.8% | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 3.1 ± 0.9 |

| Insulin+Pramlintide (Pre-Meal) | 91.4% ± 2.9% | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 0.9 ± 0.4 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Dual-Hormone Algorithm Tuning (Rodent Model)

- Instrumentation: Implant vascular catheters for continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) and dual-channel infusion pump.

- Basal Calibration: Under anesthesia, establish individual basal insulin infusion rate to maintain euglycemia (100-150 mg/dL) for 30 mins.

- Glucagon Challenge: Administer a standardized insulin bolus (0.1 U/kg) to induce a controlled descent. At a glucose threshold of 100 mg/dL, test glucagon boluses from 2-20 mcg/kg. Measure time to peak glucose and magnitude of rebound.

- Algorithm Integration: Input dose-response data into a proportional-integral-derivative (PID) or model-predictive control (MPC) algorithm. Set glucagon activation 10 mg/dL above the hypoglycemic threshold defined for insulin attenuation.

- Validation: Test the tuned algorithm against a mixed-meal challenge.

Protocol 2: Islet Perfusion Sequential Protocol

- Islet Preparation: Handpick 100 size-matched murine or human islets into a perfusion chamber.

- Baseline Perfusion: Perfuse with Krebs-Ringer Bicarbonate buffer containing 3mM glucose at 37°C, 0.5 mL/min for 60 mins.

- Pramlintide Pre-treatment: Switch to buffer containing 3mM glucose + 100 pM pramlintide for 20 mins.

- Secretagogue Stimulation: Switch to high-glucose (11mM) buffer with continued 100 pM pramlintide for 40 mins. Collect effluent at 1-min intervals for insulin/glucagon ELISA.

- Control Run: Repeat steps 1-4, omitting pramlintide in steps 3 & 4.

Protocol 3: Pramlintide-Adjunctive Therapy Workflow (Pre-Meal Dosing)

- Subject Preparation: Overnight-fasted, catheterized large animal or human subject.

- CGM Calibration: Ensure CGM is YSI-calibrated.

- Pre-Meal Intervention: 30 minutes prior to a standardized mixed-meal (e.g., 0.5 g/kg carbs):

- Control Arm: Administer insulin bolus per standard carbohydrate-counting formula.

- Intervention Arm: Administer pramlintide bolus (dose per Table 1 ratio) via subcutaneous infusion, followed by a reduced insulin bolus (typically 30-50% reduction).

- Monitoring: Monitor CGM for 6 hours post-meal. Key metrics: time to glucose peak, peak amplitude, and total AUC for glucose >180 mg/dL. Collect frequent plasma samples for amylin and insulin levels.

Visualizations

Dual-Hormone Control Loop

Pramlintide Adjunctive Action Path

Stress-Induced AP Coordination Failure

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Dual-Channel Programmable Infusion Pump (e.g., Harvard PHD ULTRA) | Allows simultaneous, independent infusion of insulin and glucagon/pramlintide with precise rate control, critical for mimicking physiological secretion patterns. |

| Non-Adsorptive Infusion Tubing (e.g., PEG-coated) | Precludes loss of peptide hormones (especially pramlintide and glucagon) via adhesion to tubing walls, ensuring accurate delivered dose. |

| Stable Glucagon Analog (e.g., Dasiglucagon) or Novel Formulation | Reduces experimental variability caused by the rapid fibrillation and degradation of native glucagon in aqueous solution. |

| Humanized In Silico Simulator (UVa/Padova T1DM Simulator) | Provides a validated platform for initial safety testing and tuning of dual-hormone algorithms prior to costly in vivo studies. |

| Specific ELISA Kits (Insulin, Glucagon, Amylin) | Essential for measuring portal-peripheral hormone gradients and confirming secretory suppression (e.g., pramlintide's effect on glucagon). |

| Hyperinsulinemic-Euglycemic Clamp Setup | Remains the gold-standard methodology to quantify changes in insulin sensitivity induced by adjunctive therapies in vivo. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs for Integrated Glucose-Insulin Research Simulations

Q1: Our multi-scale physiological model shows unrealistic oscillations in blood glucose when integrating a new subcutaneous insulin pharmacokinetic sub-model. What are the primary checks? A1: This is often a unit mismatch or time-constant disparity. Follow this protocol:

- Verify Units: Confirm all rate constants are in consistent temporal units (e.g., per minute vs. per hour). Check insulin flux units (pmol/kg/min) match glucose appearance/disappearance (mg/kg/min or mmol/kg/min).

- Scale Time Constants: Subcutaneous insulin absorption often operates on a 60-120 minute half-life, while glucose dynamics are faster. Ensure your solver (e.g., ODE15s in MATLAB, CVODE in NEURON) is configured for stiff equations. Reduce solver maximum time step to 0.1 min.

- Isolate the Sub-model: Run the new insulin PK/PD sub-model with a constant input. Output should be a smooth, non-oscillatory profile. If oscillations persist, the issue is internal to the sub-model logic.

Q2: When simulating a closed-loop insulin delivery algorithm, the in-silico clinical trial yields highly variable outcomes compared to a single patient simulation. Is this a software or modeling issue? A2: This is typically expected biological variability, but must be validated.

- Action Protocol: Run a sensitivity analysis on key parameters (e.g., insulin sensitivity, carbohydrate ratio, endogenous glucose production) using a Sobol or Latin Hypercube sampling method.

- Diagnostic Table: Compare your outcome variance to published in silico trial variance.

Table 1: Expected vs. Problematic Variance in Simulated Glucose Outcomes

| Metric | Expected Coefficient of Variation (CV) | Problematic CV | Likely Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Blood Glucose | 5-12% | >20% | Parameter distributions are too wide/unconstrained |

| Time-in-Range (70-180 mg/dL) | 8-15% | >25% | Correlations between parameters (e.g., sensitivity & carb ratio) not correctly defined |

| Hypoglycemia Events | 15-30% | >50% | Underlying population model does not match target cohort |

Q3: Our agent-based model of pancreatic beta-cell response fails to replicate first-phase insulin secretion upon glucose challenge. How to debug? A3: This indicates a missing rapid-release mechanism or incorrect calcium dynamics.

- Experimental Protocol: a. Isolate Ion Channels: Temporarily fix cytoplasmic ATP/ADP ratio to simulate constant glucose. Check if voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCC) open correctly. b. Check Docking Pools: Implement a "readily releasable pool" (RRP) of insulin granules. The first phase requires a pre-docked, primed RRP. c. Trace Calcium: Output a time-series trace of intracellular Ca²⁺ for 10 virtual cells. A sharp spike should immediately follow membrane depolarization.

Q4: Data from our continuous glucose monitor (CGM) simulator has an unnatural, "steppy" appearance lacking physiological sensor noise. How to improve realism? A4: You are likely generating clean interstitial glucose and not applying CGM-specific artifacts.

- Solution: Post-process your simulated interstitial glucose signal with:

- Low-Pass Filtering: Apply a 5-15 minute lag to simulate diffusion delay.

- Additive White Noise: Add Gaussian noise with a standard deviation of 1-2% of the reading.

- Calibration Error: Introduce a slight, slowly drifting bias (+/- 5%) over 24-hour periods.

Q5: The co-simulation between our insulin pump firmware model (in C) and glucose model (in Python) halts unpredictably. What's the best coordination strategy? A5: This is a classic co-simulation synchronization issue. Use a dedicated middleware.

- Recommended Protocol: Implement the Functional Mock-up Interface (FMI) standard. Export each sub-system as a Functional Mock-up Unit (FMU). Use a master algorithm (e.g., in Python with

FMPyor Julia) to synchronize data exchange at fixed communication intervals (e.g., every 1 minute of simulation time). Ensure all FMUs use the same solver type recommendation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for In Silico Experiments

Table 2: Essential In Silico Research Tools

| Item / Software | Function in Coordinated Glucose-Insulin Research |

|---|---|

| FMI/FMU Standard | Enables co-simulation of disparate models (e.g., device firmware + physiology) in a standardized, tool-independent way. |

| SUNDIALS (CVODE) | A robust suite of nonlinear differential/algebraic equation solvers for stiff multi-scale physiological systems. |

| Sobol.jl / SALib | Libraries for variance-based sensitivity analysis, crucial for identifying key parameters driving system coordination. |

| UVA/Padova T1D Simulator | An accepted, validated simulator of type 1 diabetes metabolism; serves as a benchmark for new model components. |

| BioFVM & PhysiCell | Frameworks for simulating pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics (PK/PD) and tissue-scale phenomena in 3D. |

| SBML & CellML | Model exchange languages to encode biological processes, ensuring reproducibility and interoperability. |

| Git & DVC (Data Version Control) | Version control for models, parameters, and simulation outputs, essential for collaborative, reproducible science. |

Visualizations of Key Workflows & Pathways

Title: Closed-Loop In Silico Testing Workflow

Title: In Silico Clinical Trial Protocol

Diagnosing and Resolving Coordination Failures in Clinical and Real-World Settings

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Calibration Errors

Q1: Our in-house continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) sensor shows high mean absolute relative difference (MARD) >15% after two-point calibration against a reference method (YSI). What are the primary investigative steps?

A: High post-calibration error indicates fundamental sensor drift or instability. Follow this protocol:

- Verify Reference Method: Ensure the benchtop analyzer (e.g., YSI 2900) has been calibrated and maintained per manufacturer protocol. Use fresh standards.

- Check Calibration Solution Integrity: Confirm age, storage conditions, and sterility of calibration solutions. Degradation can introduce systematic bias.

- Execute a Drift Analysis Protocol:

- Immerse sensors in a stable, stirred glucose solution at 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L).

- Record sensor signal every minute for 6 hours at 37°C.

- Calculate the coefficient of variation (CV) of the signal. A CV >10% indicates significant electrochemical noise or instability.

- Analyze Calibration Data Fit: Plot reference glucose (x) vs. sensor signal (y). A poor linear fit (R² < 0.9) suggests non-linear sensor response or interference.

Table 1: Common Calibration Error Sources & Diagnostic Tests

| Error Source | Diagnostic Experiment | Acceptable Metric | Typical Failure Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unstable Reference | Triplicate measurements of a single sample on reference analyzer. | Standard Deviation | > ±2 mg/dL (±0.1 mmol/L) |

| Sensor Signal Drift | Stable glucose bath test (6 hrs). | Signal Coefficient of Variation | > 10% |

| Poor Linearity | Two-point calibration across range (e.g., 40 & 400 mg/dL). | R-squared (R²) of fit | < 0.90 |

| Biofouling | Pre- vs. post-explant sensor sensitivity check in vitro. | Sensitivity Loss | > 15% |

Q2: During dynamic clamp studies, we observe a lag between the reference blood glucose and the subcutaneous CGM signal, confounding our algorithm testing. How can we characterize and compensate for this?

A: The physiological lag (typically 5-15 minutes) is a key coordination challenge. Use this protocol to quantify it:

- Hyperglycemic Clamp Experiment: In an animal model, rapidly elevate blood glucose via dextrose infusion.

- Synchronous Sampling: Measure arterial blood glucose (reference) and interstitial glucose (via microdialysis) every 2-5 minutes.

- Time-Series Analysis: Apply cross-correlation analysis between the reference and CGM signals. The time offset at maximum correlation is the system lag.

- Implement Compensation: Test moving-average filters or deconvolution algorithms (e.g., using a diffusion model) to align signals. Validate by comparing the time-compensated CGM trace to the reference during a separate hypoglycemic clamp.

Diagram 1: Protocol for Quantifying Physiological Glucose Monitoring Lag

Signal Dropouts

Q3: In our ambulatory animal studies, intermittent CGM signal loss occurs. How do we systematically determine if the cause is wireless telemetry or sensor failure?

A: Isolate the failure domain with this stepwise diagnostic workflow.

Diagram 2: Signal Dropout Diagnostic Decision Tree

Experimental Protocol for RF Interference Testing:

- Place the experimental subject (device implanted/attached) in a Faraday cage or anechoic chamber.

- Use a programmable signal generator to introduce controlled interference in the ISM band (e.g., 2.4 GHz).

- Monitor the telemetry receiver's Link Quality Index (LQI) or Received Signal Strength Indicator (RSSI) while systematically varying interference power.

- Correlate dropout events with LQI/RSSI thresholds and interference peaks. This confirms telemetry as the root cause.

Infusion Set Issues

Q4: During prolonged subcutaneous insulin infusion studies in rodents, we observe erratic glucose control. How can we test for infusion set failure (occlusion, leakage, tissue trauma)?

A: Infusion set failure directly disrupts the coordination of monitoring and delivery. Implement this validation protocol:

Table 2: Infusion Set Failure Modes & Detection Methods

| Failure Mode | In-Vivo Detection Method | In-Vitro Bench Test | Consequence for Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Partial Occlusion | Rising infusion pump pressure alarm (if equipped). | Measure flow rate vs. backpressure. | Under-delivery, unexplained hyperglycemia. |

| Complete Occlusion | Pump occlusion alarm; zero flow. | Verify no flow at max pump pressure. | Complete therapy failure. |

| Catheter Leakage | Visual dye study (infuse methylene blue, dissect site). | Pressure decay test in a sealed system. | Insulin loss, variable absorption. |

| Tissue Trauma/Inflammation | Histology at infusion site (H&E stain). | N/A (in-vivo only). | Altered insulin pharmacokinetics. |

Detailed Histology Protocol for Assessing Infusion Site Reaction:

- Sample Collection: After 72 hours of infusion, euthanize subject and excise tissue surrounding catheter tip.

- Fixation: Immerse in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 hours.

- Sectioning: Paraffin-embed, section at 5 µm thickness.

- Staining: Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stain.

- Scoring: Use a standardized scale (e.g., 0-4) to grade inflammatory cell infiltration (neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages) and fibrosis. Compare to a contralateral control site.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for CGM-Insulin Integration Studies

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Benchtop Glucose Analyzer (e.g., YSI 2900) | Gold-standard reference for blood/plasma glucose. Essential for sensor calibration and study validation. |

| Microdialysis System | Direct sampling of interstitial fluid (ISF) to decouple sensor performance from physiological lag. |

| Programmable Syringe Pumps (Dual-Channel) | For precise, simultaneous delivery of glucose and insulin during hyper-/hypo-glycemic clamps. |

| RF Spectrum Analyzer | Diagnose telemetry dropouts by identifying environmental interference in the wireless band used. |

| Pressure Transducer (Low Range, 0-15 psi) | Integrated in-line to monitor infusion set patency and detect early occlusions. |

| Tissue Fixative (10% NBF) | Preserves infusion site architecture for histological analysis of local tissue response. |

| Fluoroscopic Tracer (e.g., Iohexol) | Mixed with insulin to visualize infusion depot formation and leakage using real-time imaging. |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs